Cabaret Maxime: Reality Stripped Bare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fernando Lopes E Do Comendador Joe Berardo

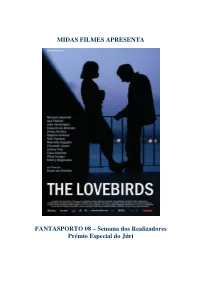

MIDAS FILMES APRESENTA FANTASPORTO 08 – Semana dos Realizadores Prémio Especial do Júri THE LOVEBIRDS O FILME THE LOVEBIRDS é uma longa-metragem que se passa em Lisboa no decorrer de uma noite onde, seis histórias se desenrolam em simultâneo. Histórias labirínticas e fragmentadas, que falam de amizade, de amor, de paixão, da falta de amor e do desejo de ser amado. Através delas, o retrato de uma cidade comovente com as emoções que nela habitam, misto de enamoramento e nostalgia, “cidade triste e alegre”, ”Lisboa e Tejo e Tudo”, como Álvaro de Campos lhe chamou ... THE LOVEBIRDS esboça encontros e desencontros. Um americano, no metro, cruza o seu olhar com uma rapariga e não resiste a persegui-la pelos becos de Alfama, na lembrança de um outro amor, a sua mulher, já falecida. Dois malandrins, sem eira nem beira, dedicam-se a pequenos roubos e não sabem se querem ser amigos ou separar-se. Um realizador de cinema faz um filme sobre boxe, sabendo que aquele será o seu último combate. Um arqueólogo que um dia chegou a Lisboa e que por cá continua, muitos anos depois, sem mesmo à noite abandonar a sua escavação e o seu amigo que tenta pela última vez trazê-lo à vida. Um taxista emigrante apaixonado por uma prostituta, que assassina, para logo a seguir ajudar uma jovem a dar à luz. Um piloto de aviões que, fora do matrimónio, acaba por se meter em situações embaraçosas… Personagens marcados pelas suas ilusões e desilusões. Meio à deriva. Uma teia de histórias perdidas, passadas em Lisboa, mas que, por terem uma ressonância universal, dão ao filme uma tonalidade absolutamente contemporânea. -

CABARET MAXIME Lands US Distribution Rights at Giant Pictures, Sets Premiere Date for February 2020

CABARET MAXIME lands US Distribution Rights at Giant Pictures, sets premiere date for February 2020 New York, NY – December, XX, 2019 – Giant Pictures has acquired the US rights for Bruno de Almeida's new movie, Cabaret Maxime, starring Michael Imperioli. It will open theatrically at the Metrograph in NYC on February 21st, ahead of a national, multi-platform rollout on March 3rd. Michael Imperioli plays Bennie Gazza, the owner of Cabaret Maxime, a nightclub in an old, red-light district where a group of colorful characters perform musical numbers, as well as burlesque and striptease acts. Bennie runs the cabaret like a tight family, dealing with each artist’s unique personality while taking care of his performer wife, Stella, who suffers from manic depression. When the once-decadent neighborhood starts to become gentrified, Bennie struggles to keep his club afloat. As the residents are being bought up and pushed out, Benny is violently threatened when he refuses to sell. The pressure builds to a dramatic climax as Benny is forced to take a stand against the powers that be. Michael Imperioli is best known for his Emmy-winning role as Christopher Moltisanti on the HBO television series, The Sopranos. In 1990, he made his film debut as Spider in Martin Scorsese's, Goodfellas. He has since appeared in more than 90 feature films and television series. He has worked with such notable directors and actors as Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Abel Ferrara, Peter Jackson, Walter Hill, Mary Harron, Cindy Sherman, Ben Gazzara, Robert De Niro, Rachel Weisz, Christopher Walken, Joe Pesci, Edie Falco, James Gandolfini, and many others. -

OPERAÇÃO OUTONO De Bruno De Almeida 28 De Fevereiro De 2013

OPERAÇÃO OUTONO de Bruno de Almeida _ 28 de Fevereiro de 2013 sinopse "Operação Outono" foi o nome de código dado à operação levada a cabo pela PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado) com o objectivo claro de assassinar o general Humberto Delgado. A operação, bem-sucedida, culminou com a sua morte a 13 de Fevereiro de 1965, na herdade de Los Almerines, próximo da ribeira de Olivença, no limite jurídico entre Portugal e Espanha. A acção do filme decorre entre Portugal, Espanha, Argélia, Marrocos, França e Itália entre os anos 1964 e 1981, desde a preparação da operação até ao caso em tribunal, já depois da revolução de Abril. Através do uso de algumas imagens de arquivo, Bruno de Almeida ("The Lovebirds") realiza um "thriller" político tendo como base o livro "Humberto Delgado, Biografia do General Sem Medo", de Frederico Delgado Rosa, neto do general, onde são reveladas novas pistas sobre o assassínio de um homem que se tornou num dos ícones pela liberdade e contra a ditadura de Salazar. Produzido por Paulo Branco, conta ainda com a participação dos actores John Marcello Urgeghe, João d'Ávila, Nuno Lopes, Pedro Efe, Diogo Dória, Luís Lima Barreto, Adriano Carvalho, José Nascimento, Ana Padrão, Cleia Almeida, Carla Chambel e Camané. ficha técnica Título original: Operação Outono (Portugal, 2012, 92 min.) Realização: Bruno de Almeida Argumento: Bruno de Almeida, Frederico Delgado Rosa, John Frey Interpretação: John Ventimiglia, Diogo Dória, Nuno Lopes Fotografia: Edmundo Diaz Som: Ricardo Leal, António Pedro Figueiredo Montagem: Roberto Perpignani Música: Dead Combo Produção: Paulo Branco Estreia: 25 de Outubro de 2012 Distribuição: Clap Filmes Classificação: M/12 anos Time Out, Novembro de 2012 Eis uma das grandes surpresas no que ao cinema português diz respeito: apesar de vir do terreno do cinema mais independente e low-budget, Bruno de Almeida sai-se de forma notável no seu primeiro empreendimento de grande fôlego, uma reconstituição da operação que levou à morte de Humberto Delgado às mãos da PIDE e do julgamento dos principais envolvidos. -

Cast and Crew

About Cast and Crew CAST MICHAEL IMPERIOLI is best known for his Emmy-winning role as Christopher Moltisanti on the HBO television series, The Sopranos. In 1990, he made his film debut as Spider in Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas. He has since appeared in more than 90 feature films and television series. He has worked with such notable directors and actors as Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Abel Ferrara, Peter Jackson, Walter Hill, Mary Harron, Cindy Sherman, Ben Gazzara, Robert De Niro, Rachel Weisz, Christopher Walken, Joe Pesci, Edie Falco, James Gandolfini, and many others. He also has long been active on the New York theater scene as an actor, writer, director and producer. He wrote several episodes of The Sopranos and was a Co-Writer and Executive Producer on Spike Lee's Summer of Sam. In 2009, he wrote, produced, and directed his first film, The Hungry Ghosts. Since 2018, he has been performing excerpts from his novel, The Perfume Burned His Eyes, at nightclubs and theaters in the USA and Europe. This is Michael’s third film with Bruno de Almeida. ANA PADRÃO is a well-known Portuguese film actress. Since 1987, she has appeared in more than eighty films, and has worked with such acclaimed European film directors as Fernando Lopes, Raoul Ruiz, Mário Barroso and João César Monteiro. She is regarded by Portuguese critics as one of the best actresses of her generation. In 2019, Ana won the SPA Award for best actress with Cabaret Maxime, her fourth film with Bruno de Almeida. JOHN VENTIMIGLIA is known for his role as Artie Bucco in the HBO television series, The Sopranos. -

Fado – Matriz Para Uma (Nova) Política Cultural Externa

Fado – Matriz para uma (nova) Política Cultural Externa. Uma Estratégia Cultural ao serviço de Portugal «Quem vê o Fado como coisa do passado, Não entende que este Fado É o agora do futuro». Fernando Girão1 «É tarde demais para ser pessimista! A cultura, a educação, a investigação e inovação são recursos inesgotáveis!». Home 2 1 GIRÃO, Fernando, Fado Cor do Sentimento, poema interpretado por Joana Amendoeira, 2008. 2 BERTRAND, Yann Arthus, HOME, in http://www.home-2009.com/us/index.html, 2008, visualizado a 3 de Setembro de 2010, pelas 21:33. Liliana RC_2012 1 Fado – Matriz para uma (nova) Política Cultural Externa. Uma Estratégia Cultural ao serviço de Portugal ÍNDICE Agradecimentos............................................................................................................................4 Índice de Figuras..........................................................................................................................6 Lista de Acrónimos....................................................................................................................... 7 Resumo........................................................................................................................................ 8 Abstract........................................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUÇÃO........................................................................................................................... 10 1.1. Objecto de estudo e operacionalização -

Detentores De Espécies CITES E Autóctones

Legenda da lista dos detentores de espécimes de espécies CITES e autóctones, registados ao abrigo da Portaria n.º 85/2018, de 27 de março A Propagação de Plantas B Criador G Jardim Botânico M Madeiras P Particular/ detentor de furão PO Colecionador pré-Convenção Q Promotor de exposições S Entidade Cientifica T Comerciante TX Taxidermista X Captura de espécimes no meio marinho fora da jurisdição de qualquer Estado Z Parque Zoológico Necessitam de registo ao abrigo da Portaria n.º 85/2018, de 27 de março, A) Todas as pessoas, singulares ou coletivas, que detenham ou exerçam atividades que impliquem a detenção de espécimes de espécies incluídas nos anexos A, B e C do Regulamento (CE) n.º 338/97, do Conselho, de 9 de dezembro de 1996, desde que promovam a transferência de espécimes. B) Todas as pessoas, singulares ou coletivas, que detenham ou exerçam atividades que impliquem a detenção dos seguintes espécimes: 1. Espécimes de espécies de aves autóctones ou de outras espécies de fauna e de flora incluídas no âmbito de aplicação do Decreto-Lei n.º 140/99, de 24 de abril, com a redação conferida pelo Decreto -Lei n.º 49/2005, de 24 de fevereiro, e pelo Decreto - Lei n.º 156 -A/2013, de 8 de novembro; 2. Espécimes de espécies incluídas no âmbito da regulamentação da Convenção de Berna. N.º Registo Portaria Titular 85/2018 15PT0194T 4 Your Pet Unip. 18PT0179T 766 Gallery, Lda 13PT0217T A casa da Bicharada -Unip. Lda. 16PT0160T A Casinha dos Pássaros 18PT0295T A Flor do Espargal Flores e Decoração, Lda 19PT0047T A Graça & Silva, Lda. -

The Sheep Thief, New York Encounter and on the Run with the Kind Permission of the Directors

Institut for Informations og Medievidenskab Aarhus Universitet p.o.v. A Danish Journal of Film Studies Editor: Richard Raskin Number 9 March 2000 Department of Information and Media Science University of Aarhus 2 p.o.v. number 9 March 2000 Udgiver: Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab, Aarhus Universitet Niels Juelsgade 84 DK-8200 Aarhus N Oplag: 750 eksemplarer Trykkested: Repro-Afdeling, Det Humanistiske Fakultet Aarhus Universitet ISSN-nr.: 1396-1160 Omslag & lay-out Richard Raskin Articles and interviews Copyright © 2000 the authors. Reproduction of stills from The Sheep Thief, New York Encounter and On the Run with the kind permission of the directors. The publication of this issue of p.o.v. was made possible by grants from the Aarhus University Research Foundation and The Danish Film Institute. All correspondence should be addressed to: Richard Raskin Department of Information and Media Science Niels Juelsgade 84 DK-8200 Aarhus N, DENMARK e-mail: [email protected] fax: (45) 89 42 1952 telephone: (45) 89 42 1973 All issues of p.o.v. can be found on the Internet at our new address: http://imv.aau.dk/publikationer/pov/POV.html The contents of this journal are registered in the Film Literature Index. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The principal purpose of p.o.v. is to provide a framework for collaborative publication for those of us who study and teach film at the Department of Information and Media Science at Aarhus University. We will also invite contributions from colleagues in other departments and at other universities. Our emphasis is on collaborative projects, enabling us to combine our efforts, each bringing his or her own point of view to bear on a given film or genre or theoretical problem. -

A Produção De Operação Outono Um Filme De Bruno De Almeida

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Artes e Letras A Produção de Operação Outono Um filme de Bruno de Almeida Iana de Oliveira Fareleiro Relatório para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Cinema (2º ciclo de estudos) Orientadora: Prof. Doutora Manuela Penafria Covilhã, Outubro 2011 AGRADECIMENTOS De uma forma geral, agradeço a todas as pessoas que directa ou indirectamente contribuíram para o sucesso do meu estágio. Um sincero obrigado a toda a equipa técnica, que me integrou de forma notável, ajudando- me sempre que fosse preciso. À minha família pelo esforço, paciência e amor. Ao professor José Luís Carvalhosa, o grande mentor desta parceria com o Paulo Branco e por ter sido um elemento catalisador nas minhas escolhas. À professora Doutora Manuela Penafria, pela orientação e disponibilidade. Por fim, um especial agradecimento à equipa de produção: à Ana Pinhão pela confiança depositada e a toda a equipa pela disponibilidade e paciência. ii RESUMO O presente relatório de estágio enquadra-se na disciplina de Estágio Curricular do último ano do Mestrado em Cinema, leccionado na Faculdade de Artes e Letras, da Universidade da Beira Interior. O estágio decorreu na produtora Alfama Films. Neste relatório poder-se-ão encontrar descritas actividades desenvolvidas ao longo do estágio, os locais de rodagem, e muitos outros assuntos pertencentes ao ramo da Produção. No final, encontra-se uma reflexão crítica onde me expresso acerca das dificuldades deste meio profissional. Na conclusão realço aquilo que para mim foi fundamental no estágio e refiro a experiência e o que aprendi ao ter trabalhado com um realizador como Bruno de Almeida. -

Paulo Branco

PAULO BRANCO Paulo Branco was born in Lisbon in 1950. He starts his career as a producer in 1979 between Paris and Lisbon. Nowadays, he embodies one of the most important figures of independent production in the world. Key player of auteur cinema, he is recognized for having given their first chances to numerous aspiring filmmakers who turned into immense cinematographers, offering them the opportunity to make their screen debut. So far, he has produced over 300 films and has worked with the most renowned film directors in the world such as David Cronenberg, Jerzy Skolimowski, Wim Wenders, Chantal Akerman, Alain Tanner, Werner Schroeter, André Téchiné, Andrzej Zulawski, Christophe Honoré, Olivier Assayas, Sharunas Bartas, Cédric Kahn, Lucas Belvaux, Valéria Bruni- Tedeschi, João César Monteiro, Paul Auster, Philippe Garrel, Mathieu Amalric, Andrzej Zulawski, among many others. His career has particularly been branded with an intense collaboration, during more than 20 years, with Raúl Ruiz (Time regained, Three lives and only one death ) and with Manoel de Oliveira (Francisca, Abraham’s valley, The satin … slipper ) … P A U L O B R A N C O 1 His contribution to the dynamics of independent cinema is as remarkable as the extent of his international visibility. Since the very beginning of his career, Paulo Branco has established his presence in the greatest international film festivals. He was the president of the Jury of the Official Selection in Competition at the Locarno Film Festival (2011), Lecce Film Festival (2011), Lucca Film Festival (2016) and the ‘Spirit of Fire’ Festival in Khanty-Mansiysk, Siberia (2018). -

Fernando Lopes

FERNANDO LOPES 7 - 31 março 2014 Nascido em Alvaiázere, chega a Lisboa em 1945 e apaixona-se pelo cinema com HANGMEN ALSO DIE de Fritz Lang, praticando uma cinefilia autodidata nas salas de cinema da cidade (rodagem) e no Cineclube Imagem. Da sua formação fazem parte o trabalho na televisão pública portuguesa onde começa em 1957, depressa descobrindo na montagem o seu espaço natural; a aprendizagem académica na London School of Film Technique frequentada graças a uma bolsa do Fundo Nacional de Cinema entre 1959 e 61, onde toma contacto direto com NÓS POR CÁ TODOS BEM NÓS POR CÁ TODOS o “free cinema”, se torna espectador do British Film Institute e tem a oportunidade de um estágio com Nicholas Ray em THE SAVAGE INNOCENTS; a posterior atividade retomada na RTP paralelamente à realização de curtas-metragens para cinema. Realiza a primeira longa, BELARMINO, a convite de António da Cunha Telles, no ano anterior a uma residência de um mês nos Estados Unidos com uma bolsa da Fundação Fulbright (que lhe permite conviver com Jean Renoir em Los Angeles), reunindo-se depois ao grupo que elabora o documento “O Ofício do Cinema em Portugal”, dirigido à Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian e decisivo para o seu apoio ao cinema através da cooperativa Centro Português de Cinema, de que é presidente. Entre 1972 e 1974 assume a direção da nova série da revista Cinéfilo, que Fernando Lopes (1935-2012) deu, juntamente com Paulo Rocha, os passos que puseram em tem grande influência e deixa um assinalável rasto, voltando à RTP em 1978 para dirigir o marcha o Cinema Novo Português nos anos sessenta, como ele assumindo-se uma sua figura segundo canal da estação pública e, mais tarde, o seu departamento de coproduções. -

A-Noite Julho2019.Pdf

noite, esse espaço de tempo em que a cada 24 horas por obra e graça da rotação da Terra o Sol está abaixo da linha do horizonte e a escuridão A domina acalmando ou despertando a imaginação ou a melancolia, é um motivo clássico, na literatura, na música ou na pintura. É de representações no cinema que trata este Ciclo a ela dedicado, em variações noturnas e notívagas, movidas por impulsos afins. É a noite repleta de histórias, devaneios, confissões ou intimidades inconfessáveis, febre, poesia, susto, aventuras reais e sonhadas, sombras escuras, cintilações, rasgos luminosos, espaços compostos a escuro, figuras errantes, personagens acordadas. É a energia da noite, libertada por sobressaltos amantes, boémios, temperamentais, enredados à superfície, mergulhados em profundezas. São noites de expressão intimista – os noturnos, e de vida entre crepúsculos – os notívagos. Este Ciclo A Noite convoca géneros clássicos, tão clássicos como a comédia, o musical e o western, e evidentemente o urbano noir, por onde passa o crime, nem sempre o castigo, na sua essência hollywoodiana e na transfiguração de universos pessoais, também de vanguarda, modernos e contemporâneos; reúne olhares livres, burlescos, de opereta, diletantes, contemplativos, emocionais, apocalípticos de vertente romântica, como a dos vampiros apaixonados para os quais há aqui lugar; atravessa sensivelmente um século, entre o XX “do cinema” e o presente XXI, em latitudes e temperaturas de gama distinta. A nota de fantasia musical e de coreografia dançada dos filmes de Walter Ruttmann (IN DER NACHT, 1931) e de Maya Deren (INTO THE NIGHT, 1959) é a tónica do programa, composto no gosto pela noite, pelos da noite. -

Michael Imperioli É O Protagonista Do Mais Recente Filme De Bruno De Almeida

COMUNICADO DE IMPRENSA 28 / 05 / 2018 ‘CABARET MAXIME’ ESTREIA A 31 DE MAIO MICHAEL IMPERIOLI É O PROTAGONISTA DO MAIS RECENTE FILME DE BRUNO DE ALMEIDA O realizador Bruno de Almeida regressa ao grande écran numa coprodução entre Portugal e os Estados Unidos que reúne atores dos dois países, com ‘Cabaret Maxime’, um filme inteiramente rodado em Lisboa que estreia nos cinemas nacionais a 31 de maio e que conta com Michael Imperioli (‘Os Sopranos’) no principal papel. Bruno de Almeida regressa com o seu grupo de atores nova-iorquinos, muitos dos quais de ‘Os Sopranos’, com os quais trabalha há mais de vinte anos: Michael Imperioli, John Ventimiglia, Nick Sandow, Drena De Niro, Sharon Angela, John Frey, Arthur Nascarella, fizeram vários filmes com o realizador, a quem se juntam em ‘Cabaret Maxime’ David Proval (‘Means Streets’ de Martin Scorsese e ‘Os Sopranos’) e Mike Starr. O grupo estende-se a Lisboa, onde se destacam Ana Padrão, com quem Bruno de Almeida já fez quatro filmes, Manuel João Vieira, Miss Suzie e convidados especiais como a cantora Selma Uamusse, Celeste Rodrigues e Phil Mendrix. ‘Cabaret Maxime’ retrata a história de Bennie Gaza (Michael Imperioli), o dono de um cabaret num velho bairro de má fama, onde um grupo de artistas apresenta números musicais, de burlesco, comédia e strip-tease. Bennie dirige o cabaret como uma família unida, lidando com as personalidades peculiares de cada artista ao mesmo tempo que toma conta de Stella (Ana Padrão), a sua mulher bipolar. Quando o velho bairro, há muito decadente, começa a sofrer um processo de gentrificação, Bennie tem que lutar para manter o seu clube à tona.