A Varve Record of Increased 'Little Ice Age' Rainfall Associated With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanology and Mineral Deposits

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D

ARCTIC VOL. 54, NO. 2 (JUNE 2001) P. 157– 161 Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D. ROBINSON1 (Received 30 May 2000; accepted in revised form 25 September 2000) ABSTRACT. Peatlands are a particularly good medium for trapping and preserving tephra, as their surfaces are wet and well vegetated. The extent of tephra-depositing events can often be greatly expanded through the observation of ash in peatlands. This paper uses the presence of the White River tephra layer (1200 B.P.) in peatlands to extend the known distribution of this late Holocene tephra into the Mackenzie Valley, northwestern Canada. The ash has been noted almost to the western shore of Great Slave Lake, over 1300 km from the source in southeastern Alaska. This new distribution covers approximately 540000 km2 with a tephra volume of 27 km3. The short time span and constrained timing of volcanic ash deposition, combined with unique physical and chemical parameters, make tephra layers ideal for use as chronostratigraphic markers. Key words: chronostratigraphy, Mackenzie Valley, peatlands, White River ash RÉSUMÉ. Les tourbières constituent un milieu particulièrement approprié au piégeage et à la conservation de téphra, en raison de l’humidité et de l’abondance de végétation qui règnent en surface. L’observation des cendres contenues dans les tourbières permet souvent d’élargir notablement les limites spatiales connues des épisodes de dépôts de téphra. Cet article recourt à la présence de la couche de téphra de la rivière White (1200 BP) dans les tourbières pour agrandir la distribution connue de ce téphra datant de l’Holocène supérieur dans la vallée du Mackenzie, située dans le Nord-Ouest canadien. -

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Evolution of the Western Avalon Zone and Related Epithermal Systems

Open File NFLD/3318 GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR SECTION FALL FIELD TRIP FOR 2013 (September 27 to September 29) EVOLUTION OF THE WESTERN AVALON ZONE AND RELATED EPITHERMAL SYSTEMS Field Trip Guide and Background Material Greg Sparkes Geological Survey of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources PO Box 8700 St. John’s, NL, A1B 4J6 Canada September, 2013 GAC Newfoundland and Labrador Section – 2013 Fall Field Trip 2 Table of Contents SAFETY INFORMATION .......................................................................................................................... 4 General Information .................................................................................................................................. 4 Specific Hazards ....................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Regional Geology of the Western Avalon Zone ....................................................................................... 7 Epithermal-Style Mineralization: a summary ........................................................................................... 8 Trip Itinerary ........................................................................................................................................... 10 DAY ONE FIELD TRIP STOPS ............................................................................................................... -

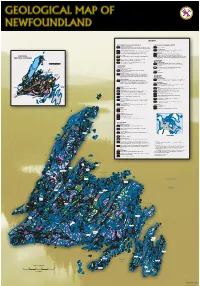

Geology Map of Newfoundland

LEGEND POST-ORDOVICIAN OVERLAP SEQUENCES POST-ORDOVICIAN INTRUSIVE ROCKS Carboniferous (Viséan to Westphalian) Mesozoic Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and minor carbonate rocks; intercalated marine, Gabbro and diabase siliciclastic, carbonate and evaporitic rocks; minor coal beds and mafic volcanic flows Devonian and Carboniferous Devonian and Carboniferous (Tournaisian) Granite and high silica granite (sensu stricto), and other granitoid intrusions Fluviatile and lacustrine sandstone, shale, conglomerate and minor carbonate rocks that are posttectonic relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and carbonate rocks; subaerial, bimodal Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks; may include some Late Silurian rocks Gabbro and diorite intrusions, including minor ultramafic phases Silurian and Devonian Posttectonic gabbro-syenite-granite-peralkaline granite suites and minor PRINCIPAL Shallow marine sandstone, conglomerate, limey shale and thin-bedded limestone unseparated volcanic rocks (northwest of Red Indian Line); granitoid suites, varying from pretectonic to syntectonic, relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies (southeast of TECTONIC DIVISIONS Silurian Red Indian Line) TACONIAN Bimodal to mainly felsic subaerial volcanic rocks; includes unseparated ALLOCHTHON sedimentary rocks of mainly fluviatile and lacustrine facies GANDER ZONE Stratified rocks Shallow marine and non-marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, including Cambrian(?) and Ordovician 0 150 sandstone, shale and conglomerate Quartzite, psammite, -

GAC - Newfoundland and Labrador Section Abstracts: 2019 Spring Technical Meeting

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 11:15 Atlantic Geology Journal of the Atlantic Geoscience Society Revue de la Société Géoscientifique de l'Atlantique GAC - Newfoundland and Labrador Section Abstracts: 2019 Spring Technical Meeting Volume 55, 2019 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060421ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2019.007 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Atlantic Geoscience Society ISSN 0843-5561 (imprimé) 1718-7885 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce document (2019). GAC - Newfoundland and Labrador Section Abstracts: 2019 Spring Technical Meeting. Atlantic Geology, 55, 243–250. https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2019.007 All Rights Reserved ©, 2019 Atlantic Geology Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Geological Association of Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Section ABSA TR CTS 2019 Spring Technical Meeting St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador The annual Spring Technical Meeting was held on February 18 and 19, 2019, in the Johnson GEO CENTRE on scenic Signal Hill in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. The meeting kicked-off Monday evening with a Public Lecture entitled “Meteors, Meteorites and Meteorwrongs of NL” by Garry Dymond from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. -

Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes

35133_Geo_Michigan_Cover.qxd 11/13/07 10:26 AM Page 1 “The Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes” is written to augment any introductory earth science, environmental geology, geologic, or geographic course offering, and is designed to introduce students in Michigan and the Great Lakes to important regional geologic concepts and events. Although Michigan’s geologic past spans the Precambrian through the Holocene, much of the rock record, Pennsylvanian through Pliocene, is miss- ing. Glacial events during the Pleistocene removed these rocks. However, these same glacial events left behind a rich legacy of surficial deposits, various landscape features, lakes, and rivers. Michigan is one of the most scenic states in the nation, providing numerous recre- ational opportunities to inhabitants and visitors alike. Geology of the region has also played an important, and often controlling, role in the pattern of settlement and ongoing economic development of the state. Vital resources such as iron ore, copper, gypsum, salt, oil, and gas have greatly contributed to Michigan’s growth and industrial might. Ample supplies of high-quality water support a vibrant population and strong industrial base throughout the Great Lakes region. These water supplies are now becoming increasingly important in light of modern economic growth and population demands. This text introduces the student to the geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes region. It begins with the Precambrian basement terrains as they relate to plate tectonic events. It describes Paleozoic clastic and carbonate rocks, restricted basin salts, and Niagaran pinnacle reefs. Quaternary glacial events and the development of today’s modern landscapes are also discussed. -

Volcanic Bedrock Lakeshore Community Abstract

Volcanic Bedrock Lakeshore CommunityVolcanic Bedrock Lakeshore, Abstract Page 1 Community Range Prevalent or likely prevalent Infrequent or likely infrequent Photo by Michael A. Kost Absent or likely absent Overview: Volcanic bedrock lakeshore, a sparsely In Michigan, the most extensive areas occur on Isle vegetated community, is dominated by mosses and Royale, where there are over 150 miles (240 km) of lichen, with only scattered coverage of vascular plants. bedrock shoreline, including several nearby smaller This Great Lakes coastal plant community, which has islands, such as Washington, Thompson, Amygdaloid, been defined broadly to include all types of volcanic Conglomerate, Long, and Caribou islands. On the bedrock, including basalt, conglomerate composed of Keweenaw Peninsula, volcanic bedrock lakeshore volcanic rock, and rhyolite, is located primarily along extends along more than 40 miles (60 km) of shoreline, the Lake Superior shoreline on the Keweenaw Peninsula including Manitou Island east of the mainland. Volcanic and Isle Royale. bedrock lakeshore is prevalent in Subsections IX.7.2 (Calumet) and IX.7.3 (Isle Royale) and occurs locally Global/State Rank: G4G5/S3 within Subsection IX.2 (Michigamme Highland) (Albert 1995; Albert et al. 1997a, 1997b, 2008). Range: Volcanic bedrock lakeshore occurs where volcanic rock is exposed along the Lake Superior Rank Justification: Volcanic bedrock lakeshore has shoreline, including Isle Royale and the Keweenaw been extensively sampled in Michigan as part of a Peninsula in Michigan, as well as along the shoreline survey and classification of bedrock shorelines along in Ontario and Minnesota. In Ontario, the arctic- the entire Michigan Great Lakes shoreline (Albert et alpine flora is relatively rare along the Great Lakes al. -

Geological Association of Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Section

Geological Association of Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Section ABSA TR CTS 2019 Spring Technical Meeting St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador The annual Spring Technical Meeting was held on February 18 and 19, 2019, in the Johnson GEO CENTRE on scenic Signal Hill in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. The meeting kicked-off Monday evening with a Public Lecture entitled “Meteors, Meteorites and Meteorwrongs of NL” by Garry Dymond from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Tuesday featured oral presentations from students and professionals on a wide range of geoscience topics. As always, this meeting was brought to participants by volunteer efforts and would not have been possible without the time and energy of the executive and other members of the section. We are also indebted to our partners in this venture, particularly the Alexander Murray Geology Club, the Johnson GEO CENTRE, Geological Association of Canada, Department of Earth Sciences (Memorial University of Newfoundland), and the Geological Survey of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Natural Resources. We are equally pleased to see the abstracts published in Atlantic Geology. Our thanks are extended to all of the speakers and the editorial staff of the journal. JAMES CONLIFFE AND ALEXANDER PEACE TECHNICAL PROGRAM CHAIRS GAC NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR SECTION ATL ANTIC GEOLOGY 55, 243 - 250 (2019) doi: 10.4138/atlgeol.2019.007 Copyright © Atlantic Geology 2019 0843-5561|19|00243-250 $2.20|0 ATLANTIC GEOLOGY · VOLUME 55 · 2019 244 process results in the production of highly reducing, Automatic microearthquake locating using characteristic ultra-basic fluids that cause a characteristic travertine functions in a source scanning method deposit when these fluids emerge. -

Canada and Western U.S.A

Appendix B – Region 12 Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk: Canada and Western U.S.A. S.K. Brown1, R.S.J. Sparks1, K. Mee2, C. Vye-Brown2, E.Ilyinskaya2, S.F. Jenkins1, S.C. Loughlin2* 1University of Bristol, UK; 2British Geological Survey, UK, * Full contributor list available in Appendix B Full Download This download comprises the profiles for Region 12: Canada and Western U.S.A. only. For the full report and all regions see Appendix B Full Download. Page numbers reflect position in the full report. The following countries are profiled here: Region 12 Canada and Western USA Pg.491 Canada 499 USA – Contiguous States 507 Brown, S.K., Sparks, R.S.J., Mee, K., Vye-Brown, C., Ilyinskaya, E., Jenkins, S.F., and Loughlin, S.C. (2015) Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk. In: S.C. Loughlin, R.S.J. Sparks, S.K. Brown, S.F. Jenkins & C. Vye-Brown (eds) Global Volcanic Hazards and Risk, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. This profile and the data therein should not be used in place of focussed assessments and information provided by local monitoring and research institutions. Region 12: Canada and Western USA Description Region 12: Canada and Western USA comprises volcanoes throughout Canada and the contiguous states of the USA. Country Number of volcanoes Canada 22 USA 48 Table 12.1 The countries represented in this region and the number of volcanoes. Volcanoes located on the borders between countries are included in the profiles of all countries involved. Note that countries may be represented in more than one region, as overseas territories may be widespread. -

The Crater Island Assemblage, Amisk Lake (Part of NTS 63L-9} 1

The Crater Island Assemblage, Amisk Lake (Part of NTS 63L-9} 1 B.A. Reilly Reilly, B.A. (1994): The Crater Island Assemblage, Amisk Lake (part of NTS 63L-9); in Summary of Investigations 1994, Sask atchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Energy Mines, Misc. Rep. 94-4. The main objective this summer was to complete revi the past few years coupled with geochemical and iso sion mapping of the south-central Amisk Lake area, and tope studies (Watters et al., in press; Stern et al., in improve the understanding of the relationships between press a and b) has led to the recognition of several dis the West Amisk and Muskeg Bay assemblages to the tinct lithotectonic assemblages (Figure 1) (Reilly et al., west and the Sandy Bay Assemblage to the east. Ap in press) in the region. proximately 200 km2 were mapped at 1:50 000 scale during the month of August in an area extending from Greenstone assemblages on the west side of Amisk the south shore of Missi Island to the edge of the Pre Lake are dominated by 1882 to 1888 Ma (Heaman et cambrian Shield at the south end of Amisk Lake (most al., 1993; Stern and Lucas, in press) felsic to intermedi of this area is covered by Amisk Lake), thus bridging ate calc-alkaline island arc volcanic rocks underlain by the gap in revisional geological mapping which existed largely tholeiitic island arc basalts2 (Fox, 1976a and b; between the east and west shores of Amisk Lake, ex Walker and Watters, 1982; Ashton, 1990, 1992; Watters cluding central and eastern Missi Island. -

Southern Arctic

ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Southern Arctic Ecosystem Classification Group Department of Environment and Natural Resources Government of the Northwest Territories 2012 ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES SOUTHERN ARCTIC This report may be cited as: Ecosystem Classification Group. 2012. Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories – Southern Arctic. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT, Canada. x + 170 pp. + insert map. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Northwest Territories. Ecosystem Classification Group Ecological regions of the Northwest Territories, southern Arctic / Ecosystem Classification Group. ISBN 978-0-7708-0199-1 1. Ecological regions--Northwest Territories. 2. Biotic communities--Arctic regions. 3. Tundra ecology--Northwest Territories. 4. Taiga ecology--Northwest Territories. I. Northwest Territories. Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources II. Title. QH106.2 N55 N67 2012 577.3'7097193 C2012-980098-8 Web Site: http://www.enr.gov.nt.ca For more information contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-8064 Fax: (867) 873-0293 About the cover: The small digital images in the inset boxes are enlarged with captions on pages 28 (Tundra Plains Low Arctic (north) Ecoregion) and 82 (Tundra Shield Low Arctic (south) Ecoregion). Aerial images: Dave Downing. Main cover image, ground images and plant images: Bob Decker, Government of the Northwest Territories. Document images: Except where otherwise credited, aerial images in the document were taken by Dave Downing and ground-level images were taken by Bob Decker, Government of the Northwest Territories. Members of the Ecosystem Classification Group Dave Downing Ecologist, Onoway, Alberta.