A Desultory Treatise on Outer Cape Cod Biogeography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To See Checklist

Detail from Abstract Harbor Scene by Morris Davidson HARBOR TO BAY FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION July 6–September 13, 2020 Curated by Christine McCarthy 460 COMMERCIAL STREET | PROVINCETOWN MA | PAAM.ORG | 508-487-1750 HARBOR TO BAY Detail from Boats in the Harbor by John Whorf For over a century, the bodies of water that bay in Plymouth, Cape Cod enjoyed an early surround Province-town have been a source reputation for its valuable fishing grounds, of inspiration for artists and visitors alike. This and for its harbor: a naturally deep, protected exhibition brings together approximately 30 basin that was considered the best along the artworks in all media spanning decades that coast. In 1654, the Governor of the Plymouth depict Provincetown Harbor or Provincetown Colony purchased this land from the Chief of Bay. In concert with the 400th anniversary the Nausets, for a selling price of two brass of the first landing of the Pilgrims, below is kettles, six coats, 12 hoes, 12 axes, 12 knives a brief history of Provincetown Harbor culled and a box. from Wikipedia, the US Census and the Town That land, which spanned from East Harbor of Provincetown. (formerly, Pilgrim Lake)—near the pres- On November 9, 1620, the Pilgrims aboard the ent-day border between Provincetown and Mayflower sighted Cape Cod while en route to Truro—to Long Point, was kept for the benefit the Colony of Virginia. After two days of failed of Plymouth Colony, which began leasing fish- attempts to sail south against the strong win- ing rights to roving fishermen. -

Project Summaries Section 604B Water Quality

PROJECT SUMMARIES SECTION 604B WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLANNING PROGRAM FFY 1998-2010 Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Haas, Acting Assistant Commissioner 2010 MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION SECTION 604B WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLANNING PROGRAM PROJECT SUMMARIES FFY 1998-2010 Prepared by: Gary Gonyea, 604(b) Program Coordinator Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs Ian Bowles, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Laurie Burt, Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Hass, Acting Assistant Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director 2010 NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY Limited copies of this report are available at no cost by written request to: Division of Watershed Management Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection 627 Main Street, 2nd floor Worcester, MA 01608 This report is also available from MassDEP’s home page on the World Wide Web at http://mass.gov/dep/water/grants.htm A complete list of reports published since 1963, entitled, “Publications of the Massachusetts Division of Watershed Management, 1963 - (current year),” is available by writing to the DWM in Worcester. The report can also be found at MassDEP’s web site, at: http://www.mass.gov/dep/water/resources/envmonit.htm#reports TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE Introduction v Table 1 Number of 604(b) Projects and Allocation of Grant Funds by Basin (1998-2010) vi Projects by Federal Fiscal Year FFY 98 98-01 Urban Watershed Management in the Mystic River Basin ..........................................……. 1 98-02 Assessment and Management of Nonpoint Source Pollution in the Little River Subwatershed 2 98-03 Upper Blackstone River Watershed Wetlands Restoration Plan .................................…. -

Second Five-Year Review Report for the Wyckoff/Eagle Harbor Superfund Site Was September 26, 2007 Completed

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Second Five-Year Review Report for the Wyckoff/Eagle Harbor Superfund Site Bainbridge Island, Washington September 26, 2007 Wyckoff/Eagle Harbor Superfund Site Bainbridge Island, Washington Second Five-Year Review Report Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.....................................................................................v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................ix FIVE-YEAR REVIEW SUMMARY FORM.............................................................................................xi 1. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE FIVE-YEAR REVIEW ................................................................................................1 1.2 AUTHORITY FOR CONDUCTING THE FIVE-YEAR REVIEW...................................................................1 1.3 WHO CONDUCTED THE FIVE-YEAR REVIEW ......................................................................................2 1.4 REVIEW STATUS.................................................................................................................................2 2. SITE CHRONOLOGY..........................................................................................................................3 3. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................9 -

Annual Report of the Board of Harbor Commissioners, 1877 and 1878

: PUBLIC DOCUMENT .No. 33. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Board of Harbor Commissioners FOR THE YEAR 18 7 7. BOSTON ftanb, &berg, & £0., printers to tfje CommcntntaltJ, 117 Franklin Street. 1878. ; <£ommontocaltl) of Jllaesacfjusetta HARBOR COMMISSIONERS' REPORT. To the Honorable the Senate and the Home of Representatives of the Common- wealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor Commissioners, in accordance with the provisions of law, respectfully submit their annual Report. By the operation of chapter 213 of the Acts of 1877, the number of the Board was reduced from five to three members. The members of the present Board, having been appointed under the provisions of said Act, were qualified, and entered upon their duties on the second day of July. The engineers employed by the former Board were continued, and the same relations to the United States Advisory Council established. It was sought to make no change in the course of proceeding, and no interruption of works in progress or matters pending and the present Report embraces the business of the entire year. South Boston Flats. The Board is happy to announce the substantial completion of the contracts with Messrs. Clapp & Ballou for the enclosure and filling of what has been known as the Twenty-jive-acre 'piece of South Boston Flats, near the junction of the Fort Point and Main Channels, which the Commonwealth by legis- lation of 1867 (chapter 354) undertook to reclaim with mate- rial taken for the most part from the bottom of the harbor. In previous reports, more especially the tenth of the series, the twofold purpose of this work, which contemplated a har- 4 HARBOR COMMISSIONERS' REPORT. -

Project Summaries Section 604B Water Quality Management Planning

PROJECT SUMMARIES SECTION 604B WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLANNING PROGRAM FFY 1998-2018 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Matthew A. Beaton, Secretary Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Martin Suuberg, Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director 2018 MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION SECTION 604B WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLANNING PROGRAM PROJECT SUMMARIES FFY 1998-2018 Prepared by: Gary Gonyea, 604b Program Coordinator Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Matthew A. Beaton, Secretary Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Martin Suuberg, Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director 2018 NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION 8 NEW BOND STREET WORCESTER, MA 01606 This Report is available from MassDEP's home page on the Internet at http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/water/grants/watersheds-water-quality.html Copies of the final reports for selected projects are available on CD upon request . TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE Introduction ix Table 1 Number of 604(b) Projects and Allocation of Grant Funds by Basin (1998-2018) x Projects by Federal Fiscal Year FFY 98 98-01 Urban Watershed Management in the Mystic River Basin ..........................................……. 1 98-02 Assessment and Management of Nonpoint Source Pollution in the Little River Subwatershed 2 98-03 Upper Blackstone River Watershed Wetlands Restoration Plan .................................…. 3 98-04 Assessment of Current Quality and Projected Nutrient Loading: Menemsha Pond and Chilmark Great Pond ………………………………………………………………… … 4 FFY 99 99-01 Priority Land Acquisition Assessment for Cape Cod: Phase 2 …………………………… 5 99-02 Nutrient Loading to Two Great Ponds: Tisbury Great Pond and Lagoon Pond …………… 6 99-03 Cape Cod Coastal Nitrogen Loading Studies ……………………………………………… 7 99-04 Chicopee River Watershed Basin Assessment ………………………………...………. -

HIRUDINEA and Oligochleta COLLECTED in the GREAT LAKES REGION

CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE BIOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAI{ES. HIRUDINEA AND OLIGOCHlETA COLLECTED IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION. By J. PERCY MOORE, Ph. D. 153 B. B. F. 1905--11 Blank page retained for pagination CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE BIOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES. HIRUDINEA AND OLIGOCH£TA COLLECTED IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION. By J. PERCY MOORE, Ph. D. I. HIRUDINEA. The operations of the field parties directed by Prof.•Tacob Reighard in connec tion with the biological survey of the Great Lakes yielded a large number of carefully preserved and labeled leeches, the detailed study and identification of which have required considerable time and furnished interesting data on variation that can be more profitably utilized elsewhere than in this report. The bulk of the collection comes from the western end of the lake, where a few specimens were collected in the vicinity of Put-in Bay during the summer of 1898, and a great many at the same place, at other points about the Bass Islands, at Sandusky, and along the Canadian and Ohio shores during the following summer; in the latter season also smaller collections Were taken at Erie, Pa., and other places in eastern Lake Erie. As no systematic collecting seems to have been done in the small lakes, ponds, and creeks in which the large, jawed leeches abound, no representatives of the family Hirudinidre are included; nor was any attempt made to gather the fish leeches, and the single vial containing Ichthyobdellidre unfortunately met with an accident that prevents the determination of its contents." On the other hand, the shore collecting was very thorough, and the families Glossiphonidre and Herpobdellidre are probably represented by every species found in such situations in Lake Erie, and in most cases by many beautifully pre served specimens. -

Season Notice of Race

Notice of Race and Event Sailing Instructions (As Amended) 1 Front Street, Beringer Bowl Overnight Ocean PO Box 487 Marblehead, MA Race 01945 July 22 – 23, 2016 781-631-3100 Presented in Partnership with Rumson’s Rum 1.1 Event: The Beringer Bowl Overnight Ocean Race will be held on July 22–23, 2016. The Organizing Authority is the Boston Yacht Club (BYC). This event is a qualifier for the MBSA, North Shore Ocean, Marblehead Coney Ledge and Marblehead Overall. 2.1 Eligibility: Open to PHRF boats with valid PHRFNE Handicap Rating Certificates and that meet the requirements of this Notice of Race and Event Sailing Instructions. (a) Divisions: PHRF Racing, PHRF Cruising, Doublehanded PHRF Racing (separate start), and OCS for Cruising Canvas, and a One-design class for 3 or more boats. 2.2 Registration: Entry and payment at http://www.bostonyc.org/yachting/racing. Entries should be submitted before 2359 hrs on July 18, 2016. For information contact [email protected]. 2.3 Fees: $125 less discounts of $5 for US SAILING members and $5 for MBSA members. For entries after July 18 an additional late fee of $25 will be charged. 2.4 Handicap System: PHRF Time on Distance will be used. 3 Rules: This Event will be governed by the Mass Bay Sailing Association General Sailing Instructions except as changed by these Event Sailing Instructions. (a) The ISAF ORC Special Regulations for a Category 3 Event shall apply, except as to ISAF ORC OSR Nos. 3.17, 3.20, 3.28.4b), 4.23.1, where the ISAF ORC Special Regulations for a Category 4 Event shall apply. -

Plymouth Colony

Name: ____________________________________________ Date: _______________________ Plymouth Colony Overview: Plymouth Colony was an English colony from 1620-1691. It is also known as New Plymouth or Plymouth Bay Colony. It was one of the earliest successful colonies in North America and took part in the first Thanksgiving in 1621. Origins of Colonists: The original group of settlers were known as separatists because they had gone against the King of England and the Anglican Church. The group was under religious persecution to leave England. In 1619 they obtained a land patent from the London Virginia Company to let them settle a colony in North America. In 1620 the colonists left for America on the ships Mayflower and Speedwell. Leaving: The two ships left South Hampton England on August 15th, 1620. The Mayflower had 90 passengers and the Speedwell had 30 passengers. The Speedwell had immediate problems and had to go back. The Mayflower returned and it finally left for America with 102 passengers on September 16th, 1620. Voyage: The voyage from England to America at these times would typically take 2 months. In the first month the Mayflower had smooth sailing. In the second month they were hit by a strong winter storm which killed two of the passengers. Arrival: The Mayflower first arrived at Provincetown Harbor on November 11th, 1620. The following day Susanna White gave birth to Peregrine White who was the first child born to a pilgrim in the New World. While exploring the area they ran into a Native American tribe and went looking for another area. The ship soon came across an area they agreed to settle. -

97492Main Cacomap1.Pdf

Race Point Beach National Park Service Old Harbor Life-Saving Station Museum 0 1 2 Kilometers R a T ce 1 2 Miles IN 0 PO Province Lands E C North A Visitor Center R Provincetown Po Muncipal in (seasonal) Race Airport Road t A D S ut Point HatchesHatches ik A h e s N o Light HarborHarbor d D ri n R ze a o D T d L P Beech Forest Trail a U o H d N r N e w E o T a rr S t in v o n io i g w n n C o a c n o f l e e v S c T o e n t ea i r o v f o u s r P w h 6 r o A TLANTIC OCEAN o Clapps n re Pond Street B ou Pilgrim 6A P nd A a Herring Monument R r A y Cove and Provincetown Museum D B PROVINCETOWN U O rd N L Beach fo E IC d Pilgrim Lake S National Park Service ra B U.S.-Coast Guard Station (East Harbor) 6A B e a c h H h ig e P H a o h d g d snack bar in i a P R O V I N C E T O W N t H e d H A R B O R a Pilgrim Heights (seasonal) H o R Sa Small’s lt Swamp M ea Dike Trail Pilgrim do Submerged Spring w at extreme Trail National Park Service high tide. -

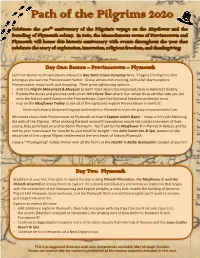

Path of the Pilgrims 2020

Path of the Pilgrims 2020 Celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrim’s voyage on the Mayflower and the founding of Plymouth colony. In 2020, the Massachusetts towns of Provincetown and Plymouth will honor this historic anniversary with events throughout the year that celebrate the story of exploration, innovation, religious freedom, and thanksgiving. Day One: Boston – Provincetown – Plymouth Sail from Boston to Provincetown onboard a Bay State Cruise Company ferry. Imagine the Pilgrim’s first landing as you sail into Provincetown Harbor. Group arrives mid-morning, with a full day to explore Provincetown, enjoy lunch and shopping. Three great sightseeing options: • Visit the Pilgrim Monument & Museum to learn more about this important story in America’s history. • Explore the dunes and province lands on an Art’s Dune Tour where four-wheel drive vehicles take you out onto the historic sand dunes on the Provincetown, Cape Cod National Seashore protected lands. • Hop on the Mayflower Trolley to see all of the sights and explore Provincetown in comfort! Motorcoach departs Boston with luggage and transfers to Plymouth to re-join the group at approximately 6 pm. Afternoon cruise from Provincetown to Plymouth on board Captain John’s Boats – enjoy a ferry ride following the path of the Pilgrims. After realizing the land around Provincetown would not sustain the needs of their colony, they continued on and landed in Plymouth. You’ll sail by the Mayflower II in Plymouth Harbor, and be met by your motorcoach for transfer to your hotel for tonightZ ~ the John Carver Inn & Spa, located on the actual site of the original Pilgrim settlement in the very heart of historic Plymouth. -

Appendix C SUPPORTING INFORMATION

CAPE COD WATER RESOURCES RESTORATION PROJECT Final Watershed Plan− Areawide Environmental Impact Statement Appendix C SUPPORTING INFORMATION CONTENTS Appendix C-1. Air Quality Conformity Analysis C-1 Appendix C-2. Massachusetts Category 5 Waters C-5 Appendix C-3. Summary of Potential Essential Fish Habitat Off Cape Cod C-9 Appendix C-4. CCWRRP Essential Fish Habitat Assessment C-27 Appendix C-5. Threatened and Endangered Species in Barnstable County and C-45 Adjacent Coastal Waters November 2006 CAPE COD WATER RESOURCES RESTORATION PROJECT Final Watershed Plan− Areawide Environmental Impact Statement Appendix C-1. Air Quality Conformity Analysis Calculation Procedures for Determining Air Emissions In order to evaluate the applicability of this Clean Air Act statute, annual air emissions were calculated for each of the three mitigation tasks. Air emissions were estimated based on equipment types, engine sizes, and estimated hours of operation. The calculations made were of a "screening" nature using factors provided for diesel engines in the USEPA AP-42 Emission Factor document (EPA 1995). The emission factors used were expressed in lb/hp-hr. The factors utilized were as follows: • 0.00668 lb CO/hp-hr • 0.031 lb NOx/hp-hr • 0.00072 lb PM10/hp-hr • 0.00205 lb SO2/hp-hr Emissions were calculated by simply multiplying the usage hours by the equipment horsepower and then by emission factor. To be complete, emissions were calculated for the four primary internal combustion engine related air pollutants. Total project emissions were calculated by adding the number of specific projects anticipated over a given 12-month period. -

Conservation, Public and Open Space

L UC KY LN JA ME S W ES T RD E V PINE BANK RD A BOURNE WATER ST E T PERR V Y R E D T A N N S R OR T TH H S T A ILL G D S E R E O E S V V R R S E FR A E C A O D V N D T U A N K L E O N L Q R L R N E R O E A S I A P C M E L E E O H N I T H K L IS L C C O T S E B T T B R O A B B S W E E D A D H H O R Y T DA A U LE ST A W A R DWAR D E G N D W WIN O H L T A SANDWICH N TARA N S E L S B R B R A D Y R D R U H LN CEDAR LAKE S LE B P B R U D R B R D A E CORDWOOD GE I RED N C P D E T O L R S U E R N D T R E Y D T R S D 8 E R H ST D FIDDLERS COVE D E C BAY RD D R R T Y R C S T T N I H S E U G RANDS CANAL O P I E D IN C A P D H R B L L S O T E A C N A L E R M N LN A TROUT POND A O W N E I P D M U W C A E R S G R R RD A T DEE I L E D N E Y O N WE O R STW D R E S N N E D ID T L R A E H RD LDE R E C N Y T R D A W R D R D I R G LLO A B W R D IVE E FIELD LOR D F TRICIA RD N DR EN R D R R CO J D E V R AM N E WILD HARBOR RD I W N O N D YE WESTO WE S N RD STON RD LN E V GR A OVE ST E T V E GLE S N AV A V E E T A T W S W T S HIGH KIR K E LAND A H E I S VE IL DGERTON N L DR V A S C E O I D LO VERFIELD N D HIL W T LSIDE AVE E AVE AY A R D E G WICKE R R A N TRE C E RD D I WICKE O E L RT R R N EE W C RD I I R R N C L T RYST A SL D R D A AL O R S W O IN PRING AV D O O E M N S V P ILVER B R EA D C A CH A VE D E M RD E A R K LI L WIL R N HUNT O L ILL F I S ST H R L E DO V I T T I D E D R N H L E HO T S D LLI P S S S T D W R N E BIR L O CH A U LN N S W O L Y T A D W R R VIEW R RRY LN E LONG FER E F NW H D OO B A D T L RD K S A U PL N S R I CURLEY BL O A VD E M K S