Operational Guidance on Kosovo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haradinaj Et Al. Indictment

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA CASE NO: IT-04-84-I THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST RAMUSH HARADINAJ IDRIZ BALAJ LAHI BRAHIMAJ INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, charges: Ramush Haradinaj Idriz Balaj Lahi Brahimaj with CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OR CUSTOMS OF WAR, as set forth below: THE ACCUSED 1. Ramush Haradinaj, also known as "Smajl", was born on 3 July 1968 in Glodjane/ Gllogjan* in the municipality of Decani/Deçan in the province of Kosovo. 2. At all times relevant to this indictment, Ramush Haradinaj was a commander in the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës (UÇK), otherwise known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). In this position, Ramush Haradinaj had overall command of the KLA forces in one of the KLA operational zones, called Dukagjin, in the western part of Kosovo bordering upon Albania and Montenegro. He was one of the most senior KLA leaders in Kosovo. 3. The Dukagjin Operational Zone encompassed the municipalities of Pec/Pejë, Decani/Deçan, Dakovica/Gjakovë, and part of the municipalities of Istok/Istog and Klina/Klinë. As such, the villages of Glodjane/Gllogjan, Dasinovac/Dashinoc, Dolac/Dollc, Ratis/Ratishë, Dubrava/Dubravë, Grabanica/Grabanicë, Locane/Lloçan, Babaloc/Baballoq, Rznic/Irzniq, Pozar/Pozhare, Zabelj/Zhabel, Zahac/Zahaq, Zdrelo/Zhdrellë, Gramocelj/Gramaqel, Dujak/ Dujakë, Piskote/Piskotë, Pljancor/ Plançar, Nepolje/Nepolë, Kosuric/Kosuriq, Lodja/Loxhë, Barane/Baran, the Lake Radonjic/Radoniq area and Jablanica/Jabllanicë were under his command and control. -

The Differential Impact of War and Trauma on Kosovar Albanian Women Living in Post-War Kosova

The Differential Impact of War and Trauma on Kosovar Albanian Women Living in Post-War Kosova Hanna Kienzler Department of Anthropology McGill University, Montreal June 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © 2010 Hanna Kienzler Abstract The war in Kosova had a profound impact on the lives of the civilian population and was a major cause of material destruction, disintegration of social fabrics and ill health. Throughout 1998 and 1999, the number of killings is estimated to be 10,000 with the majority of the victims being Kosovar Albanian killed by Serbian forces. An additional 863,000 civilians sought or were forced into refuge outside Kosova and 590,000 were internally displaced. Moreover, rape and torture, looting, pillaging and extortion were committed. The aim of my dissertation is to rewrite aspects of the recent belligerent history of Kosova with a focus on how history is created and transformed through bodily expressions of distress. The ethnographic study was conducted in two Kosovar villages that were hit especially hard during the war. In both villages, my research was based on participant observation which allowed me to immerse myself in Kosovar culture and the daily activities of the people under study. The dissertation is divided into four interrelated parts.The first part is based on published accounts describing how various external power regimes affected local Kosovar culture, and how the latter was continuously transformed by the local population throughout history. The second part focuses on collective memories and explores how villagers construct their community‟s past in order to give meaning to their everyday lives in a time of political and economic upheaval. -

10 Years of Impunity for Enforced Disappearances and Abductions in Kosovo

BURYING THE PAST 10 YEARS OF IMPUNITY FOR ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES AND ABDUCTIONS IN KOSOVO Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion – funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Amnesty International Publications First published in 2009 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2009 Index: EUR 70/007/2009 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. cover photo : Kosovo Albanian relatives of the disappeared demonstrate with photographs of their missing relatives, Pristina, Kosovo. © Courtesy of the Kosovo Government Commission on Missing Persons and Mr Shkelzen Rexha. back cover top : Petrija Piljević, a Serbian woman, abducted in June 1999, with her son. © Private back cover bottom : Daka Asani, a Romani man, abducted in August 1999. -

Freedom House, Its Academic Advisers, and the Author(S) of This Report

Kosovo by Group for Legal and Political Studies Capital: Pristina Population: 1.816 million GNI/capita, PPP: $10,200 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores NIT Edition 2017 2018 2009 2011 2016 2010 2012 2013 2014 2015 National Democratic Governance 5.25 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 Electoral Process 4.50 4.25 4.50 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.50 Civil Society 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 Independent Media 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.25 5.00 5.00 Local Democratic Governance 5.25 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.50 Judicial Framework and Independence 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 Corruption 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 5.75 5.75 Democracy Score 5.14 5.07 5.18 5.18 5.25 5.14 5.14 5.07 4.96 4.93 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

Prishtina Insight

January 16 - 29, 2015 l #149 l Price 1€ Nation: Opinion: Prishtina Vucic reassures We need to Kosovo Serbs talk about Insight during visit. Charlie. PAGE 4 PAGE 14 High-risk,FROM high-paying jobs in warzones offer escape KOSOVOfrom economic stagnation at home. PAGE 6 TO KABUL 2 n January 16-29, 2015 n Prishtina Insight PageTwoKOSOVO-SERBIA RELATIONS IN 2015 Dialogue will con- tinue in Brussels in from the editor February: Serbian PM Aleksandar Vucic visited Kosovo this week but The forgotten Christmas did not meet with his Serbia’s 2015 OSCE counterparts, saying he Chairmanship: Serbia bomber story would see Kosovo Prime assumed the chairman- Minister Isa Mustafa ship of the OSCE at the Some three weeks have passed, finally taking a more constructive in Brussels when the beginning of the year and we still know little about why approach to its former province. Kosovo-Serbia dialogue from Switzerland. The a man from Belgrade, Slobodan But with Belgrade’s people in- resumes in February. organization, composed Gavric — reportedly an employee stalled in parliament and the gov- There are some rumors of 57 states, has its of Serbia’s Ministry of Agricul- ernment via Srpska List, Serbia’s that it may be handled biggest field mission ture — was arrested in Prishtina motives still must be looked with at the Foreign Minister in Kosovo. Serbia’s while police say he was prepar- a certain degree of suspicion. level, so that original leadership role could ing to commit an act of terrorism Still, it seems doubtful that Ser- high-level dealmakers bring downsizing in the that could have easily eclipsed bia had any role in this case. -

Republika E Kosovës International Law of the Unilateral Declaration Of

Republika e Kosovës ilepublika Kosova - Republic of Kosovo Qeveria -Vlada - Govemment Min'istria e Punëve të Jashtme-Ministarstvo lnostranih Poslova -Ministry of Foreign Affairs 17 April 2009 Sir, With reference to the request for an ~dvisory opinion submitted to the Court by the General Assembly of the United Nations on the question of the Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of lndependence by the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government of Kosovo, I have the honour to submit herewith, in accordance with Article 66 of the Statute of the Court and the Court's Ortler of 17 October 2008, the Written Contribution of the Republic of Kosovo. The Government of the Republic of Kosovo transmits thirty copies of its Written Contribution and annexes, as well ·as an electronic copy. I also transmit, for deposit in the Registry, a full-scale photographie reproduction of the Declaration oflndependence of Kosovo as signed on 17 February 2008. Accept, Sir, the assurances of my hiÎÏlconsid~ !. Sken~dr yseni Minister of oreign Affairs Representative offlie"'. epublic of Kosovo before the International Court of Justice H.E. Mr. Philippe Couvreur Registrar International Court of Justice Peace Palace 2517 KJ The Hague The Netherlands INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE ACCORDANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE UNILATERAL DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE BY THE PROVISIONAL INSTITUTIONS OF SELF-GOVERNMENT OF KOSOVO (REQUEST FOR ADVISORY OPINION) WRITTEN CONTRIBUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOSOVO 17 APRIL 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents -

Serbia and Montenegro Page 1 of 34

2005 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Serbia and Montenegro Page 1 of 34 Facing the Threat Posed by Iranian Regime | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Serbia and Montenegro Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Serbia and Montenegro is a state union consisting of the relatively large Republic of Serbia and the much smaller Republic of Montenegro.* The state union is a parliamentary democracy. The state union government's responsibilities are limited to foreign affairs, national security, human and minority rights, and internal and external economic and commercial relations. The country has a population of 10.8 million** and is headed by President Svetozar Marovic, who was elected by parliament in 2003. The Republic of Serbia is a parliamentary democracy with approximately 10.2 million inhabitants. Prime Minister Vojislav Kostunica has led Serbia's multiparty government since March 2004. Boris Tadic was elected president in June 2004 elections that observers deemed essentially in line with international standards. While civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, there were a few instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of government authority. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens and continued efforts to address human rights violations; however, numerous problems from previous years persisted. The following human rights problems were reported: -

Nationalist Crossroads and Crosshairs: on External and Internal Sources of Albanian and Serbian National Mythology

Nationalist Crossroads and Crosshairs: On External and Internal Sources of Albanian and Serbian National Mythology Matvey Lomonosov Department of Sociology McGill University, Montreal June 2018 A dissertation submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology © Matvey Lomonosov, 2018 Abstract This dissertation employs comparative historical methods to investigate the development of Albanian and Serbian national identity over the last two centuries. More narrowly, it traces the emergence and evolution of two foundational national myths: the story of the Illyrian origins of the Albanian nation and the narrative of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo. The study focuses on micro- and meso-level processes, the life course of mythmakers and specific historical situations. For this, it relies on archival data from Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia, as well as a wide body of published primary and secondary historical sources. The dissertation is composed of four separate articles. In the first article, I offer evidence that the Kosovo myth, which is often seen as a “crucial” supporting case for ethno-symbolist theory, is a modern ideological construct. For evidence, the article focuses on temporal, geographical and cultural ruptures in the supposedly long-standing “medieval Kosovo legacy” and the way the narrative was promoted among South Slavs in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It finds that Serbian-speaking diaspora intellectuals from the Habsburg Empire and the governments in Belgrade and Cetinje played crucial roles imparting the Kosovo myth to the Balkan masses. Thus, it is hard to account for the rise of national identities and local conflicts in the Balkans without a closer look at foreign intervention and the history of states and institutions. -

3Rd Annual Albanian Congress of Trauma and Emergency Surgery | Abstracts Book

Volume 3 Number 2 Supplement 3 November 2019 Focus on "Trauma and Emergency Surgery" and not only... Official publication of ASTES ISSN: 2521-8778 (print version) ISSN: 2616-4922 (electronic version) Volume 3 - Number 2 - Supplement 3 November 2019 Focus on “Trauma and Emergency Surgery” and not only… official publication of ISSN: 2521-8778 (print version) ISSN: 2616-4922 (electronic version) M & B publications Albanian Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery AJTES Official Publication of the Albanian Society for Trauma International Editorial Board Advisory Expert and Emergency Surgery -ASTES Prof. Fausto CATENA MD, PhD FACS (Italy) Chairman of the editorial board: Prof. Andrew BAKER MD, PhD, FACS (South Africa) Prof. Eliziana PETRELA, MD, PhD Asc. Prof. Agron Dogjani MD, PhD, FACS FISS (ALBANIA) Prof. Joakim JORGENSEN MD, PhD, FACS (Norway) University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania Prof. Selman URANUES MD, FACS (Austria) EditorEditor in in Chief Chief Prof. Dietrich DOLL MD, PhD, FACS (Germany) Prof. John E. FRANCIS MD, PhD, FACS (USA) Asc.Prof. Rustem CELAMI MD, PhD (Albania) Asc.Prof. Rustem CELAMI MD, PhD (Albania) Prof. Thomas B. WHITTLE MD, PhD (USA) Assistant Editors Deputy Editors Prof. Sadi BEXHETI MD, PhD (Macedonia) Deputy Editors Prof. Vilmos VECSEI, MD, PhD (Austria) Prof. Lutfi ZYLBEARI MD, PhD (Macedonia) Asc.Prof. Pantelis VASSILIU MD, PhD, FACS (Greece) Hysni BENDO MD Amarildo BLLOSHMI MD Prof.Asc.Prof. Lutfi Rudin ZYLBEARI Domi MD, MD, PhD PhD (Albania) (Macedonia) Prof. Massimo SARTELI MD, PhD, FACS (Italy) Ilir ALIMEHMETI MD, PhD (Albania) Prof. Jordan SAVESKI MD, PhD (Macedonia) Erion SPAHO MD Asc.Prof.Edvin SELMANI Rudin Domi MD, MD,PhD PhD(Albania) (Albania) Artan Bano MD, (Albania) Sonja SARACI MD Edvin SELMANI MD, PhD (Albania) Prof. -

Haradinaj Judgement

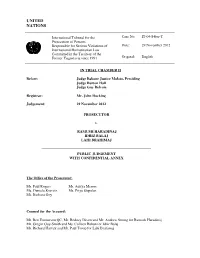

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-04-84 bis -T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 29 November 2012 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN TRIAL CHAMBER II Before: Judge Bakone Justice Moloto, Presiding Judge Burton Hall Judge Guy Delvoie Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Judgement: 29 November 2012 PROSECUTOR v. RAMUSH HARADINAJ IDRIZ BALAJ LAHI BRAHIMAJ PUBLIC JUDGEMENT WITH CONFIDENTIAL ANNEX The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Paul Rogers Mr. Aditya Menon Ms. Daniela Kravetz Ms. Priya Gopalan Ms. Barbara Goy Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Ben Emmerson QC, Mr. Rodney Dixon and Mr. Andrew Strong for Ramush Haradinaj Mr. Gregor Guy-Smith and Ms. Colleen Rohan for Idriz Balaj Mr. Richard Harvey and Mr. Paul Troop for Lahi Brahimaj CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1 II. CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE EVALUATION OF EVIDENCE........................4 III. STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION OF THE KLA IN THE DUKAGJIN ZONE ........6 A. EMERGENCE AND GENERAL STRUCTURE OF THE KLA..................................................................6 1. KLA General Staff...................................................................................................................6 2. Number of KLA forces in 1998...............................................................................................7 3. The KLA zones -

Public Perception Survey and Public Dialogue About Future Truth And

Public perception survey and public dialogue about future Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Kosovo Public perception survey and public dialogue about future TRC of Kosovo Public perception survey and public dialogue about future Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Kosovo February 2020, Prishtina Public perception survey and public dialogue about future TRC of Kosovo Colophon Nora Ahmetaj, (author) Kathelijne Schenkel, PAX (author) Kelli Muddell, ICTJ (editor) Mateo Porciuncula, ICTJ (editor) Bleona Bicaj, UBO consulting (survey data analysis) Tringa Krasniqi, UBO consulting (survey data analysis) Kushtrim Koliqi, Integra (publisher) Acknowledgments Powered by Integra In partnership with New Social Initiative (NSI) Authorized by the Preparatory Team for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Supported by the US Embassy in Kosovo, Embassy of Switzerland in Kosovo and Rockefeller Brothers Fund With thanks to the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) and PAX for advice and review throughout Public perception survey and public dialogue about future TRC of Kosovo Content Executive Summary - Key findings Introduction Methodology - Quantitative research - Qualitative research Findings - Demographic profile of respondents - Views on truth, reconciliation and major actors - Views on Reconciliation - Knowledge on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission - Views towards the Truth and Reconciliation Commission - Preferences for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Kosovo Conclusions Recommendations 3 Public perception survey and public dialogue about future TRC of Kosovo List of Figures Figure 1. Do you belong to any of the following legally-established categories? Figure 2. How do you evaluate the change in the following areas since the end of the war? Figure 3. How do you evaluate the change in the following areas since the end of the war? Figure 4. -

Kosovo by Krenar Gashi

Kosovo by Krenar Gashi Capital: Pristina Population: 1.8 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,100 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators 2015. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores Kosovo 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Electoral Process 4.75 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.25 4.50 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 Civil Society 4.25 4.25 4.00 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 4.00 3.75 3.75 Independent Media 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 National Democratic Governance 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.25 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 Local Democratic Governance 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.25 5.00 5.00 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 Corruption 6.00 6.00 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 Democracy Score 5.36 5.36 5.21 5.14 5.07 5.18 5.18 5.25 5.14 5.14 NOTES: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest.