Astrochemical Pathways to Complex Organic and Prebiotic Molecules: Experimental Perspectives for in Situ Solid-State Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laboratory Studies for Planetary Sciences

Laboratory Studies for Planetary Sciences A Planetary Decadal Survey White Paper Prepared by the American Astronomical Society (AAS) Working Group on Laboratory Astrophysics (WGLA) http://www.aas.org/labastro Targeted Panels: Terrestrial Planets; Outer Solar System Satellites; Small Bodies Lead Author: Murthy S. Gudipati Ice Spectroscopy Lab, Science Division, Mail Stop 183-301, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109. [email protected], 818-354-2637 Co-Authors: Michael A'Hearn - University of Maryland [email protected], 301-405-6076 Nancy Brickhouse - Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics [email protected], 617-495-7438 John Cowan - University of Oklahoma [email protected], 405-325-3961 Paul Drake - University of Michigan [email protected], 734-763-4072 Steven Federman - University of Toledo [email protected], 419-530-2652 Gary Ferland - University of Kentucky [email protected], 859-257-879 Adam Frank - University of Rochester [email protected], 585-275-1717 Wick Haxton - University of Washington [email protected], 206-685-2397 Eric Herbst - Ohio State University [email protected], 614-292-6951 Michael Mumma - NASA/GSFC [email protected], 301-286-6994 Farid Salama - NASA/Ames Research Center [email protected], 650-604-3384 Daniel Wolf Savin - Columbia University [email protected], 212-854-4124, Lucy Ziurys – University of Arizona [email protected], 520-621-6525 1 Brief Description: The WGLA of the AAS promotes collaboration and exchange of knowledge between astronomy and planetary sciences and the laboratory sciences (physics, chemistry, and biology). -

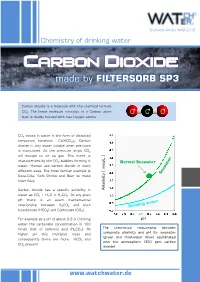

Carbon Dioxide - Made by FILTERSORB SP3

Technical Article MAR 2015 Chemistry of drinking water Carbon dioxide - made by FILTERSORB SP3 Carbon dioxide is a molecule with the chemical formula CO2. The linear molecule consists of a Carbon atom O C O that is doubly bonded with two Oxygen atoms. CO2 exists in water in the form of dissolved temporary hardness Ca(HCO3)2. Carbon dioxide is only water soluble when pressure is maintained. As the pressure drops CO2 will escape to air as gas. This event is characterized by the CO2 bubbles forming in /L ] Normal Seawater water. Human use carbon dioxide in many meq different ways. The most familiar example is Coca-Cola, Soft Drinks and Beer to make them fizzy. Carbon dioxide has a specific solubility in [ Alkalinity water as CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3. At any given pH there is an exact mathematical relationship between H2CO3 and both bicarbonate (HCO3) and Carbonate (CO3). For example at a pH of about 9.3 in Drinking pH water the carbonate concentration is 100 The theoretical relationship between times that of carbonic acid (H2CO3). At carbonate alkalinity and pH for seawater higher pH this multiplier rises and (green and freshwater (blue) equilibrated consequently there are more HCO and 3 with the atmosphere (350 ppm carbon CO present 3 dioxide) www.watchwater.de Water ® Technology FILTERSORB SP3 WATCH WATER & Chemicals Making the healthiest water How SP3 Water functions in human body ? Answer: Carbon dioxide is a waste product of the around these hollow spaces will spasm and respiratory system, and of several other constrict. chemical reactions in the body such as the Transportation of oxygen to the tissues: Oxygen creation of ATP. -

A Complete Guide to Benzene

A Complete Guide to Benzene Benzene is an important organic chemical compound with the chemical formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. As it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms, benzene is classed as a hydrocarbon. Benzene is a natural constituent of crude oil and is one of the elementary petrochemicals. Due to the cyclic continuous pi bond between the carbon atoms, benzene is classed as an aromatic hydrocarbon, the second [n]- annulene ([6]-annulene). It is sometimes abbreviated Ph–H. Benzene is a colourless and highly flammable liquid with a sweet smell. Source: Wikipedia Protecting people and the environment Protecting both people and the environment whilst meeting the operational needs of your business is very important and, if you have operations in the UK you will be well aware of the requirements of the CoSHH Regulations1 and likewise the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in the US2. Similar legislation exists worldwide, the common theme being an onus on hazard identification, risk assessment and the provision of appropriate control measures (bearing in mind the hierarchy of controls) as well as health surveillance in most cases. And whilst toxic gasses such as hydrogen sulphide and carbon monoxide are a major concern because they pose an immediate (acute) danger to life, long term exposure to relatively low level concentrations of other gasses or vapours such as volatile organic compounds (VOC) are of equal importance because of the chronic illnesses that can result from that ongoing exposure. Benzene, a common VOC Organic means the chemistry of carbon based compounds, which are substances that results from a combination of two or more different chemical elements. -

Type of Ionising Radiation Gamma Rays Versus Electro

MY9700883 A National Seminar on Application of Electron Accelerators, 4 August 1994 INTRODUCTION TO RADIATION CHEMISTRY OF POLYMER Khairul Zaman Hj. Mohd Dahlan Nuclear Energy Unit What is Radiation Chemistry? Radiation Chemistry is the study of the chemical effects of ionising radiation on matter. The ionising radiation flux in a radiation field may be expressed in terms of radiation intensity (i.e the roentgen). The roentgen is an exposure dose rather than absorbed dose. For radiation chemist, it is more important to know the absorbed dose i.e. the amount of energy deposited in the materials which is expressed in terms of Rad or Gray or in electron volts per gram. The radiation units and radiation power are shown in Table 1 and 2 respectively. Type of Ionising Radiation Gamma rays and electron beam are two commonly used ionising radiation in industrial process. Gamma rays, 1.17 and 1.33 MeV are emitted continuously from radioactive source such as Cobalt-60. The radioactive source is produced by bombarding Cobalt-59 with neutrons in a nuclear reactor or can be produced from burning fuel as fission products. Whereas, electrons are generated from an accelerator to produce a stream of electrons called electron beam. The energy of electrons depend on the type of machines and can vary from 200 keV to 10 MeV. Gamma Rays versus Electron Beam Gamma rays are electromagnetic radiation of very short wavelength about 0.01 A (0.001 nm) for a lMeV photon. It has a very high penetration power. Whereas, electrons are negatively charge particles which have limited penetration power. -

Chemical Formula

Chemical Formula Jean Brainard, Ph.D. Say Thanks to the Authors Click http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (No sign in required) AUTHOR Jean Brainard, Ph.D. To access a customizable version of this book, as well as other interactive content, visit www.ck12.org CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the FlexBook®, CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning, powered through the FlexBook Platform®. Copyright © 2013 CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org The names “CK-12” and “CK12” and associated logos and the terms “FlexBook®” and “FlexBook Platform®” (collectively “CK-12 Marks”) are trademarks and service marks of CK-12 Foundation and are protected by federal, state, and international laws. Any form of reproduction of this book in any format or medium, in whole or in sections must include the referral attribution link http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (placed in a visible location) in addition to the following terms. Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Com- mons from time to time (the “CC License”), which is incorporated herein by this reference. -

Mechanistic Studies of the Desorption Ionization

Mechanistic studies of the desorption ionization process in fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry by Jentaie Shiea A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry Montana State University © Copyright by Jentaie Shiea (1991) Abstract: The mechanisms involved in Desorption Ionization (DI) continue to be a very active area of research. The answer to the question of how involatile and very large molecules are transferred from the condensed phase to the gas phase has turned out to involve many different phenomena. The effect on Fast Atom Bombardment (FAB) mass spectra of the addition of acids to analyte bases has been quantitatively investigated. Generally, the pseudomolecular ion (M+H+) intensity increased with the addition of acid, however, decreases in ion intensity were also noted. For the practical use of FAB, it is important to clarify the reasons for this acid effect. By critical evaluation, a variety of different explanations were found. However, contrary to other studies, no unambiguous example was found in which the effect of "preformed ions" could adequately explain the observed results. The mechanistic implications of these findings are briefly discussed. The importance of surface activity in FAB has been pointed out by many researchers. A systematic study was conducted, involving the addition of negatively charged surfactants to samples containing small organic and inorganic cations. An enhancement of the positive ion spectra of these analytes was observed. The study of mass transport processes of two surfactants was performed by varying the analyte concentration and matrix temperature in FAB. The study of the desorption process in SIMS by varying the viscosity of the matrix solutions shows that such studies may help to bridge the mechanisms in solid and liquid SIMS and, in the process, increase our understanding of both techniques. -

Introduction, Formulas and Spectroscopy Overview Problem 1

Chapter 1 – Introduction, Formulas and Spectroscopy Overview Problem 1 (p 12) - Helpful equations: c = ()() and = (1 / ) so c = () / ( ) c = 3.00 x 108 m/sec = 3.00 x 1010 cm/sec a. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the longer wavelength? Convert both values to meters. -1 = 3500 cm = 4 x 1014 Hz = (1/) = (c / ) = (1/ ) = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (4 x 1014 s-1) = (1/ cm-1)(1 m/100 cm) = 2.9 x 10-6 m = 7.5 x 10-7 m = longer wavelength = lower energy b. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the higher frequency? Convert both values to Hz. = 400 cm-1 = 300 nm = (1/ ) = 1/ [(400 cm-1)(100 cm / 1 m)] = (c/) 8 -5 9 = 2.5 x 10-5 m = (3.0 x 10 m/s) / (2.5 x 10 nm)(1m / 10 nm) v = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (300 nm)(1m / 109 nm) = (c/) v = 1.0 x x 1015 s-1 = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (2.5 x 10-5 m) v = 1.2 x 1013 s-1 higher frequency c. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the smaller wavenumber? Convert both values to cm-1. = 1 m = 6 x 1010 Hz = (1 / ) -1 = ( / c) = (1 / 1m) = 1 m-1 100 cm = 100 cm-1 100 cm-1 -1 = (6 x 1010 s-1 / 3.0 x 108 m/s) = 200 m-1 -1 1 m -1 = 20,000 cm smaller wavenumber 1 m Problem 2 (p 14) - Order the following photons from lowest to highest energy (first convert each value to kjoules/mole). -

Computational Surface Modelling of Ices and Minerals of Interstellar Interest—Insights and Perspectives

minerals Review Computational Surface Modelling of Ices and Minerals of Interstellar Interest—Insights and Perspectives Albert Rimola 1,* , Stefano Ferrero 1, Aurèle Germain 2 , Marta Corno 2 and Piero Ugliengo 2,3 1 Departament de Química, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Catalonia, Spain; [email protected] 2 Dipartimento di Chimica, Università degli Studi di Torino, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (P.U.) 3 Nanostructured Interfaces and Surfaces (NIS) Centre, Università degli Studi di Torino, 10125 Torino, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-93-581-3723 Abstract: The universe is molecularly rich, comprising from the simplest molecule (H2) to complex organic molecules (e.g., CH3CHO and NH2CHO), some of which of biological relevance (e.g., amino acids). This chemical richness is intimately linked to the different physical phases forming Solar-like planetary systems, in which at each phase, molecules of increasing complexity form. Interestingly, synthesis of some of these compounds only takes place in the presence of interstellar (IS) grains, i.e., solid-state sub-micron sized particles consisting of naked dust of silicates or carbonaceous materials that can be covered by water-dominated ice mantles. Surfaces of IS grains exhibit particular characteristics that allow the occurrence of pivotal chemical reactions, such as the presence of binding/catalytic sites and the capability to dissipate energy excesses through the grain phonons. The present know-how on the physicochemical features of IS grains has been obtained by the fruitful synergy of astronomical observational with astrochemical modelling and laboratory experiments. -

Interstellar Dust Within the Life Cycle of the Interstellar Medium K

EPJ Web of Conferences 18, 03001 (2011) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/20111803001 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2011 Interstellar dust within the life cycle of the interstellar medium K. Demyk1,2,a 1Université de Toulouse, UPS-OMP, IRAP, Toulouse, France 2CNRS, IRAP, 9 Av. colonel Roche, BP. 44346, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France Abstract. Cosmic dust is omnipresent in the Universe. Its presence influences the evolution of the astronomical objects which in turn modify its physical and chemical properties. The nature of cosmic dust, its intimate coupling with its environment, constitute a rich field of research based on observations, modelling and experimental work. This review presents the observations of the different components of interstellar dust and discusses their evolution during the life cycle of the interstellar medium. 1. INTRODUCTION Interstellar dust grains are found everywhere in the Universe: in the Solar System, around stars at all evolutionary stages, in interstellar clouds of all kind, in galaxies and in the intergalactic medium. Cosmic dust is intimately mixed with the gas-phase and represents about 1% of the gas (in mass) in our Galaxy. The interstellar extinction and the emission of diffuse interstellar clouds is reproduced by three dust components: a population of large grains, the BGs (Big Grains, ∼10–500 nm) made of silicate and a refractory mantle, a population of carbonaceous nanograins, the VSGs (Very Small Grains, 1–10 nm) and a population of macro-molecules the PAHs (Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons) [1]. These three components are more or less abundant in the diverse astrophysical environments reflecting the coupling of dust with the environment and its evolution according to the physical and dynamical conditions. -

H2CS) and Its Thiohydroxycarbene Isomer (HCSH

A chemical dynamics study on the gas phase formation of thioformaldehyde (H2CS) and its thiohydroxycarbene isomer (HCSH) Srinivas Doddipatlaa, Chao Hea, Ralf I. Kaisera,1, Yuheng Luoa, Rui Suna,1, Galiya R. Galimovab, Alexander M. Mebelb,1, and Tom J. Millarc,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, University of Hawai’iatManoa, Honolulu, HI 96822; bDepartment of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199; and cSchool of Mathematics and Physics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom Edited by Stephen J. Benkovic, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, and approved August 4, 2020 (received for review March 13, 2020) Complex organosulfur molecules are ubiquitous in interstellar molecular sulfur dioxide (SO2) (21) and sulfur (S8) (22). The second phase clouds, but their fundamental formation mechanisms have remained commences with the formation of the central protostars. Tempera- largely elusive. These processes are of critical importance in initiating a tures increase up to 300 K, and sublimation of the (sulfur-bearing) series of elementary chemical reactions, leading eventually to organo- molecules from the grains takes over (20). The subsequent gas-phase sulfur molecules—among them potential precursors to iron-sulfide chemistry exploits complex reaction networks of ion–molecule and grains and to astrobiologically important molecules, such as the amino neutral–neutral reactions (17) with models postulating that the very acid cysteine. Here, we reveal through laboratory experiments, first sulfur–carbon bonds are formed via reactions involving methyl electronic-structure theory, quasi-classical trajectory studies, and astro- radicals (CH3)andcarbene(CH2) with atomic sulfur (S) leading to chemical modeling that the organosulfur chemistry can be initiated in carbonyl monosulfide and thioformaldehyde, respectively (18). -

Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (Pahs)

Ambient Water Quality Criteria For Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Province of British Columbia N. K. Nagpal, Ph.D. Water Quality Branch Water Management Division February, 1993 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author is indebted to the following individual and agencies for providing valuable comments during the preparation of this document. Dr. Ray Copes BC. Ministry of Health, Victoria, BC. Dr. G. R. Fox Environmental Protection Div., BC. MOELP, Victoria, BC. Mr. L. W. Pommen Water Quality Branch, BC. MOELP, Victoria, BC. Mr. R. J. Rocchini Water Quality Branch, BC. MOELP, Victoria, BC. Ms. Sherry Smith Eco-Health Branch, Conservation and Protection, Environment Canada, Hull, Quebec Mr. Scott Teed Eco-Health Branch, Conservation and Protection, Environment Canada, Hull, Quebec Ms. Bev Raymond Integrated Programs Branch, Inland Waters, Environment Canada, North Vancouver, BC. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are organic compounds which are non- essential for the growth of plants, animals or humans; yet, they are ubiquitous in the environment. When present in sufficient quantity in the environment, certain PAHs are toxic and carcinogenic to plants, animals and humans. This document discusses the characteristics of PAHs and their effects on various water uses, which include drinking Ministry of Environment Water Protection and Sustainability Branch Mailing Address: Telephone: 250 387-9481 Environmental Sustainability PO Box 9362 Facsimile: 250 356-1202 and Strategic Policy Division Stn Prov Govt Website: www.gov.bc.ca/water Victoria BC V8W 9M2 water, aquatic life, wildlife, livestock watering, irrigation, recreation and aesthetics, and industrial water supplies. A significant portion of this document discusses the effects of PAHs upon aquatic life, due to its sensitivity to PAHs. -

Methods of Ion Generation

Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 361−375 361 Methods of Ion Generation Marvin L. Vestal PE Biosystems, Framingham, Massachusetts 01701 Received May 24, 2000 Contents I. Introduction 361 II. Atomic Ions 362 A. Thermal Ionization 362 B. Spark Source 362 C. Plasma Sources 362 D. Glow Discharge 362 E. Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) 363 III. Molecular Ions from Volatile Samples. 364 A. Electron Ionization (EI) 364 B. Chemical Ionization (CI) 365 C. Photoionization (PI) 367 D. Field Ionization (FI) 367 IV. Molecular Ions from Nonvolatile Samples 367 Marvin L. Vestal received his B.S. and M.S. degrees, 1958 and 1960, A. Spray Techniques 367 respectively, in Engineering Sciences from Purdue Univesity, Layfayette, IN. In 1975 he received his Ph.D. degree in Chemical Physics from the B. Electrospray 367 University of Utah, Salt Lake City. From 1958 to 1960 he was a Scientist C. Desorption from Surfaces 369 at Johnston Laboratories, Inc., in Layfayette, IN. From 1960 to 1967 he D. High-Energy Particle Impact 369 became Senior Scientist at Johnston Laboratories, Inc., in Baltimore, MD. E. Low-Energy Particle Impact 370 From 1960 to 1962 he was a Graduate Student in the Department of Physics at John Hopkins University. From 1967 to 1970 he was Vice F. Low-Energy Impact with Liquid Surfaces 371 President at Scientific Research Instruments, Corp. in Baltimore, MD. From G. Flow FAB 371 1970 to 1975 he was a Graduate Student and Research Instructor at the H. Laser Ionization−MALDI 371 University of Utah, Salt Lake City. From 1976 to 1981 he became I.