The Eternal Teachings of Hinduism in Everyday Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Eastern Classics Reading List, St. John's College

______________________________________________________FALL WEEK ONE • Confucius, Analects, #1-7 Any translation carried by the College Bookstore is fine, but please avoid non-scholarly translations available elsewhere. (If you use the Edward Slingerland the reading is pp. 1 – 77, but please skip the commentary, both Ancient and Modern). • Confucius, Analects #8-13 (Slingerland, pp. 78 – 152) WEEK TWO • Confucius, Analects #14-20 (Slingerland, pp. 153 – 235) • Mo Tzu, Basic Writings of Mo Tzu, Hsun Tzu, and Han Fei Tzu, translated by Burton Watson (Columbia University Press), fascicles 11, 16, 17, 19, 20, 26, 27 31, 32, 35, 39; Mo Zi, Chapter 14 “Universal Love I” and Chapter 15 “Universal Love II.” Photocopies are available in the bookstore. WEEK THREE • Mencius, Books I – II (Please choose one of the translations carried by the bookstore.) • Mencius, Books III - IV. WEEK FOUR • Mencius, Books V - VII. • Hsun Tzu, Basic Writings of Mo Tzu, Hsun Tzu, and Han Fei Tzu, translated by Burton Watson (Columbia University Press), sections 1, 2, 9, 17. WEEK FIVE • Hsun Tzu, sections 19 - 23, pp. 89 - 171. • Chuang Tzu, The Book of Chuang Tzu (selections per tutor) Please use one of the translations carried by the bookstore. If you consult the Palmer & Breully translation please supplement it with a more scholarly edition.) WEEK SIX • Chuang Tzu (selections per tutor) ___________________________________________ FALL (Continued) WEEK SEVEN • Lao Tzu, The Way of Lao Tzu, chapters 1 - 36. Commentaries are not necessary. Any translation carried in the bookstore is fine. Consulting multiple translations is encouraged. • Lao Tzu, The Way of Lao Tzu, chapters 37 – 81. WEEK EIGHT • Han Fei Tzu, fascicles 20, 21. -

Indian Philosophy 2009 - 1995

VISION IAS www.visionias.wordpress.com www.visionias.cfsites.org www.visioniasonline.com Under the Guidance of Ajay Kumar Singh ( B.Tech. IIT Roorkee , Director & Founder : Vision IAS ) PHILOSOPHY IAS MAINS: QUESTIONS TREND ANALYSIS PAPER-I: INDIAN PHILOSOPHY 2009 - 1995 Charvaka 1. Carvaka’s views on the nature of soul. Notes. (2007) 2. Discuss the theory of knowledge, according to Charvaka Philosophy. Notes. (2006) 3. Dehatmavada of Charvakas. Notes. (2004) 4. Charvak’s refutation of anumana is itself a process of anumana. Discuss. (2003) 5. State and evaluate critically Charvaka’s view that perception is the only valid source of knowledge. (2002) 6. The Charvak theory of consciousness. Short Notes. (2001) 7. Ethics of Charvaka School. Short Notes. (2000) 8. The soil is nothing but the conscious body. Notes. (1998) Jain Philosophy 1. Anekantavada. Notes ( 2009) 2. Nature of Pudgala in Jaina philosophy. Notes. (2007) 3. Explain the theory of Substance according to Jainism. Notes. (2006) 4. Jaina Definition of Dravya. Notes. (2005) 5. State and discuss the Jaina Doctrine of jiva. (2004) 6. Expound anekantvada of Jainism. It is a consistent theory of reality? Give reason. (2003) ©VISION IAS www.visioniasonline.com 1 7. Relation between anekantvada and saptabhanginaya. Notes. (2001) 8. Saptabhanginaya. Notes. (2000) 9. The Jain arguments for Anekantvada. Notes. (1999) 10. Ekantavada and Anekantvada. Notes. (1998) School of Buddhism 1. An examination of Buddhist Nairatmyavada. ( 2008) 2. “ The Madhyamika philosophy tries to adopt the mean between extreme and extreme negation.” Comment. ( 2008) 3. Four Arya Satya (Noble Truths) according to Buddhism. Notes. (2007) 4. Discuss Pratityasamutpada in Buddhism. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption

8 Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption major cause of the distortions discussed in the foregoing chapters A has been the lack of adequate study of early texts and pre-colonial Indian thinkers. Such a study would show that there has been a historical continuity of thought along with vibrant debate, controversy and innovation. A recent book by Jonardan Ganeri, the Lost Age of Reason: Philosophy in Early Modern India 1450-1700, shows this vibrant flow of Indian thought prior to colonial times, and demonstrates India’s own variety of modernity, which included the use of logic and reasoning. Ganeri draws on historical sources to show the contentious nature of Indian discourse. He argues that it did not freeze or reify, and that such discourse was established well before colonialism. This chapter will show the following: • There has been a notion of integral unity deeply ingrained in the various Indian texts from the earliest times, even when they 153 154 Indra’s Net offer diverse perspectives. Indian thought prior to colonialism exhibited both continuity and change. A consolidation into what we now call ‘Hinduism’ took place prior to colonialism. • Colonial Indology was driven by Europe’s internal quest to digest Sanskrit and its texts into European history without contradicting Christian monotheism. Indologists thus selectively appropriated whatever Indian ideas fitted into their own narratives and rejected what did not. This intervention disrupted the historical continuity of Indian thought and positioned Indologists as the ‘pioneers’. • Postmodernist thought in many ways continues this digestion and disruption even though its stated purpose is exactly the opposite. -

Charvaka's Philosophy

CHARVAKA PHILOSOPHY Shyam Priya Guest faculty, Department Of Philosohy Patna Women’s College INTRODUCTION TO CHARVAKA PHILOSOPHY • Charvaka /Lokayat philosophy is a heterodox school of Indian philosophy. • Do not believe in the authority of the Vedas. • Founder of this school is shrouded in mystery. • Brihaspati is also said to be the founder. • Charvaka derives its name from its philosophy of Eat, Drink & Be merry. • Materialistic philosopher- Charvaka accepts only materialism. CONTD. • Materialism accepts matter as the ultimate reality. • It rejects the existence of other worldly entities like God, Soul, Heaven, Life before death or after death etc. • Charvaka philosophy focuses mainly on these three issues:- 1. Metaphysics 2. Epistemology 3. Ethics CHARVAKA’S METAPHYSICS • Metaphysics is the theory of reality. • Matter is only reality, it alone is perceived. • God, soul, heaven , life before death or after death and any unperceived law cannot be believed in, because they are all beyond perception. The world is made of four elements. • Ether(Akasa) • Air(Vayu) • Fire(Agni) • Water(Jal) • Earth(Ksiti) CONTD. • The Charvaka rejects ether, because its existence cannot be perceived. • The material world is therefore is made of the four perceptible elements. • Not only non-living material objects but also living organisms, like plants animal bodies, are composed of these four elements. THERE IS NO SOUL • Being materialistic, the Charvakas do not believe in the existence of an invisible, unchangeable & immortal soul. • According to them, soul is a product of matter. It is the quality of the body & does not exist separately outside the body. • We do not perceive any soul; we perceive only the body in a conscious state. -

Philosophy, a Hope in COVID-19 Pandemic and Effect of Concept of Kaivalya Nidhi Yadav1

Philosophy Today Vol. 1 2020 Philosophy Today 2020, Vol. 1 https://philosophytoday.in Philosophy, a hope in COVID-19 pandemic and effect of concept of kaivalya Nidhi Yadav1 Abstract: Indian Philosophical Thoughts are flooded with the idea of Isolation/Kaivalya. Though Isolation is not a novel concept in Indian thought but it is determined as the only way to attain 'moksha'. The three classical systems of Indian philosophy namely - the orthodox(Astika), the heterodox(Nastika) and the Indian materialistic(Charvaka) broadly describe the concept of 'Kaivalya'. Hinduism describes the separation of Purush(soul) from Prakriti (matter)as 'kaivalya'. Buddhism describes 'Nirvana' (true knowledge) as the path to attend 'moksha'. While Jainism refers Kaivalya or kevala Jana(omniscience) as supreme wisdom or complete understanding. The current Covid-19 pandemic had also created situation of isolation but it is broadly different from the theory of Kaivalya. Covid-19 had created separation of individual from community and humans (being a social animal) can't live without community. Thus, philosophy can be used to show correct path to humans so that they can utilise this separation to attain true knowledge. 1 [email protected] 1 Philosophy Today Vol. 1 2020 The concept of Isolation/Kaivalya is Indian Philosophical Thought is greatly discussed in all the three highly motivated by spiritual motives. classical systems of Indian philosophy. People in India are religious though Samkhya or Sankhya (the oldest form religion in India is not dogmatic but of orthodox system) and Yoga ( one of Indian philosophy in not totally free the six orthodox system) had described from the fascination of religious Kaivalya as a state of liberation speculation. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 2 2nd Pada 1st Adikaranam to 8th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 45 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 53 Rachananupapattyadhikaranam :(Sutras 1-10) 53 a) Sutra 1 1700 53 172 b) Sutra 2 1714 53 173 c) Sutra 3 1716 53 174 d) Sutra 4 1726 53 175 e) Sutra 5 1730 53 176 f) Sutra 6 1732 53 177 g) Sutra 7 1737 53 178 h) Sutra 8 1741 53 179 i) Sutra 9 1744 53 180 j) Sutra 10 1747 53 181 54 Mahaddirghadhikaranam 54 a) Sutra 11 1752 54 182 [i] S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Paramanujagadakaranatvadhikaranam : 55 55 (Sutras 12-17) a) Sutra 12 1761 55 183 b) Sutra 13 1767 55 184 c) Sutra 14 1772 55 185 d) Sutra 15 1776 55 186 e) Sutra 16 1781 55 187 f) Sutra 17 1783 55 188 56 Samudayadhikaranam : (Sutras 18-27) 56 a) Sutra 18 1794 56 189 b) Sutra 19 1806 56 190 c) Sutra 20 1810 56 191 d) Sutra 21 1817 56 192 e) Sutra 22 1821 56 193 f) Sutra 23 1825 56 194 g) Sutra 24 1830 56 195 h) Sutra 25 1835 56 196 i) Sutra 26 1838 56 197 j) Sutra 27 1848 56 198 [ii] S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 57 Nabhavadhikaranam : (Sutras 28-32) 57 a) Sutra 28 1852 57 199 b) Sutra 29 1868 57 200 c) Sutra 30 1875 57 201 d) Sutra 31 1877 57 202 e) Sutra 32 1878 57 203 58 Ekasminnasambhavadhikaranam : (Sutras 33-36) 58 a) Sutra 33 1885 58 204 b) Sutra 34 1899 58 205 c) Sutra 35 1900 58 206 d) Sutra 36 1903 58 207 59 Patyadhikaranam : (Sutras 37-41) 59 a) Sutra 37 1909 59 208 b) Sutra 38 1924 59 209 c) Sutra 39 1929 59 210 d) Sutra 40 1932 59 211 e) Sutra 41 1937 59 212 [iv] S. -

Bhagat Singh's Atheism by J. Daniel Elam

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/hwj/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/hwj/dbaa007/5718851 by [email protected] on 31 January 2020 Bhagat Singh’s Atheism by J. Daniel Elam Although less well known outside of South Asia, Bhagat Singh remains one of the most celebrated anticolonial agitators and thinkers in India and Pakistan. In December 1928 under the auspices of a new revolutionary or- ganization he had helped to found, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), he assassinated British police officer J. P. Saunders to avenge the recent beating of Punjabi activist Lala Lajpat Rai; a few months later, in 1929, he threw a smoke-bomb in the Delhi Legislative Assembly, proclaimed inqilab zindbad (long live revolution), and awaited his arrest. From jail he debated M.K. Gandhi, wrote extensively, and staged hunger strikes with his fellow inmates. At the age of twenty-three, in 1931, Bhagat Singh was hanged by the British and became a martyr for the anticolonial cause – as well as for a growing revolutionary movement that challenged the moder- ation of the Nehru-led Congress Party and the asceticism of Gandhian non- violence. Especially in Punjab (both Pakistani and Indian Punjab), Bhagat Singh has sustained a vibrant afterlife, not least because of the iconographic studio portrait that he published in 1928. His image, as well as his revolu- tionary thought, continue to enjoy wide circulation today. Academics have turned their attention to the previously overlooked activist, producing a significant amount of work under the rubrics of what Kama Maclean has called, provocatively, ‘the revolutionary turn’.1 Of the essays that Bhagat Singh published in his lifetime, ‘Why I am an Atheist’ has remained especially popular. -

Indian Philosophy Prof. Dr. Satya Sundar Sethy Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology, Madras

Indian Philosophy Prof. Dr. Satya Sundar Sethy Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Module No. # 01 Lecture No. # 01 Introduction to Indian Philosophy I welcome you, all the students, viewers, for this course, this course name is Indian philosophy. (Refer Slide Time: 00:19) So, Introduction to Indian philosophy, today we will discuss, what is Indian philosophy? Why we study Indian philosophy? What is there within Indian philosophy? Once you know, so that your excite will come to know what is Indian philosophy, why at all there is an importance of Indian philosophy and still also, we are celebrating in many of the systems of Indian philosophy. So, I welcome once again to each one of you to see this and if you have any query you can ask me. Now, let us discuss first, what is Indian philosophy? There may be many question comes to your mind, like why we should read Indian philosophy? What is there in Indian philosophy? How it is important for us, if we at all will reading Indian philosophy? Now, coming to the very brief background of this Indian philosophy; Philosophy in Sanskrit, it is always said Darsana, deals with various philosophical thoughts. There are many schools, they have a different people. Therefore, there were different philosophical thoughts, of in several tradition. It never developed, just once in a particular year. It took several studies and many years to take place some of the theory in Indian philosophy. So, as you find there are different theoreticians and have their different view also. -

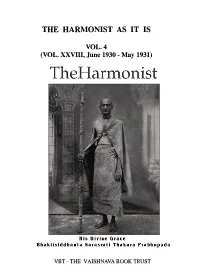

The Harmonist As It Is

THE HARMONIST AS IT IS · 'VOL.4 (VOL. XXVIII, June 1930 - May 1931) VBT -THE VAISHNAVA BOOK TRUST Published in India by VBT - THE VAISHNAVA BOOK TRUST Ananda Krishna Van, Radha Nivas Sunrakh Road, Madhuvan Colony, Sri Vrindavan Dham 281121 U.P.-INDIA Reprint of The Harmonist Magazine March 2006 - 500 collectios. Printed by Radha Press Kailash Nagar, New Delhi 110031 PREFACE If we speak of God as the Supreme, Who is above absolutely everyone and everything known and unknown to us, we must agree that there can be only one God. Therefore God, or the Absolute Truth, is the common and main link of the whole creation. Nonetheless, and although God is One, we must also agree that being the Supreme, God can also manifest as many, or in the way, shape and form that may be most pleasant or unpleasant. In other words, any sincere student of a truly scientific path of knowledge about God, must leam that the Absolute Truth is everything and much above anything that such student may have ever known or imagined. Therefore, a true conclusion of advanced knowledge of God must be that not only is God one, but also that God manifests as many. Only under this knowledge and conclusion, a perspective student of the Absolute Truth could then understand the deep purport behind polytheism, since the existence of various 'gods' cannot be other than different manifestations from the exclusive source, which is the same and only Supreme God. Nonetheless, the most particular path of knowledge that explain in detail all such manifestations or incarnations, in a most convincing and authoritative description, can be found in the vast Vedas and Vaishnava literature. -

05Xxxx Atheism and Hinduism

Atheism and Agnosticism in India Atheism in India Atheism can come in at least two flavors. The weaker one is a system of thought that simply makes no use of God. The stronger atheism will actually hold that God does not exist. In ancient Hindu thought the Charvakas and the Mimamsa schools represent the stronger form while the Vaisheshika school represents the weak form. This is all made trickier by the fact that Hindus have a great range of conceptions of Gods encompassing forms similar to the Judaeo-Christian God as well as pantheistic and polytheistic conceptions. Another complexity is added by the very different notion of orthodoxy. Unlike the clear creeds such as the Nicene creed that many Christians recognize or the universal “there is no God but Allah” of the Muslims, Hindus define orthodoxy in terms of recognition of the sacred scriptures the Vedas regardless of the particular interpretation thereof. Thus the six orthodox or astik schools are so called simply because they recognize and interpret the Vedas. (The six ancient schools are Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva Mimamsa, and Vedanta). Charvakas, Buddhists and Jains among others are considered unorthodox or nastik schools. CHARVAKAS Of the numerous schools of thought that gained prominence during the epic period as a reaction against the excessive ritualism and empty dogmatism of Vedic religion or perhaps the increasing rigidity of caste system, one school of thought attracts the attention of present day scholars not only for its radical approach to the problems of blind belief but also for its similarities with the modem day rationalism and materialism of the west. -

Sample Questions for the Department of Philosophy Set 1

Sample Questions for the Department of Philosophy Set 1 1. Who is the Father of modern philosophy? a) Locke b) Kant b) Descartes d) Plato 2. Who is the writer of “Critique of Pure Reason”? a) Hume b) Berkeley c)Kant d) Locke 3) “Cogito Ergo sum” – Who said this? a)Descartes b) Locke c)Spinoza d)Kant 4) Among them who is a Greek philosopher? a) Ayer b)Kant c)Spencer d)Aristotle 5) According to Nyaya philosophers how many pramanas are accepted? a) One b) Three c) Four d) Two 6) Which school of philosophy accept “Perception is the only Pramana”? a) Charvaka b) Buddhism c) Nyaya d) Jaina 7) Who is the father of Nyaya philosophy? a) Kanada b) Gautama c) Samkara d) Patanjali 8) “Nirguna Brahaman is the Ultimate Truth” – who said this? a) Samkara b) Kumaril c) Ramanuja d) Madhav 9) According to the Naiyayikas we perceive cowness by – a) Samanyalaksana pratyaksa b) Linga paramarsa c) Jnanalaksana Pratyaksa d) Jogoja Pratyaksa 10. Which one among the following is not purusratha? a) Dharma b) Artha c) Kama d) Isvara 11. What is the relation between A and E? a) Contrary b) Contradiction c) Sub altern d) Sub contrary 12. In logic inference means – a) Only Premiss b) Only conclusion c) Premiss and Conclusion d) None of the above 13. Conclusion of an Induction is – a) Certain b) Probable c) Truth d) Proved 14. If A is True what is I? a) True b) False c) Uncertain d) Probable 15. CAMENES is – a) 1st Figure b) 2nd Figure c) 3rd Figure d) 4th Figure 16.