EWIC Online Preview Supplement I Selected Articles B R I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meena Kumari - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Meena Kumari - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Meena Kumari(1 August 1932 - 31 March 1972) Meena Kumari (Hindi: ???? ??????), born Mahjabeen Bano, was an Indian movie actress and poetess. She is regarded as one of the most prominent actresses to have appeared on the screens of Hindi Cinema. During a career spanning 30 years from her childhood to her death, she starred in more than ninety films, many of which have achieved classic and cult status today. Kumari gained a reputation for playing grief-stricken and tragic roles, and her performances have been praised and reminisced throughout the years. Like one of her best-known roles, Chhoti Bahu, in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), Kumari became addicted to alcohol. Her life and prosperous career were marred by heavy drinking, troubled relationships, an ensuing deteriorating health, and her death from liver cirrhosis in 1972. Kumari is often cited by media and literary sources as "The Tragedy Queen", both for her frequent portrayal of sorrowful and dramatic roles in her films and her real-life story. <b> Early Life </b> Meena Kumari was the third daughter of Ali Baksh and Iqbal Begum; Khursheed and Madhu were her two elder sisters. At the time of her birth, her parents were unable to pay the fees of Dr. Gadre, who had delivered her, so her father left her at a Muslim orphanage, however, he picked her up after a few hours. Her father, a Shia Muslim, was a veteran of Parsi theater, played harmonium, taught music, and wrote Urdu poetry. -

Tawåyaf the Most Potent Visual Image Conjured up by This Word Is Undoubtedly the Tragic Character Played by the Actress Meena K

Tawåyaf The most potent visual image conjured up by this word is undoubtedly the tragic character played by the actress Meena Kumari in the 1972 film Pakeezah. Passionate and suffering, the courtesan Sahibjaan at last finds happiness outside of the world of the nautch when she can marry the man she loves. The great literary courtesan Umrao Jan Ada (in the 1905 book by Mirza Ruswa) bemoans her fate which caused her to be kidnapped from her middle-class home at the age of twelve, and sold into the sex-trade. Although the 1981 film Umrao Jaan takes some liberties with Ruswa’s novel and adds further dramatic complications, neither the literary Umrao Jan nor the screen Umrao Jaan (played by the actress Rekha) find the happiness and societal acceptance they crave. Happy ending or not (and the success of the film Pakeezah was greatly enhanced if not solely established by the tragic ending of Meena Kumari’s life from alcoholism just a few weeks after the film was released), the image of the courtesan tends to be steeped in a mixture of decadence and debauchery. Home of the courtesan, Lucknow’s legendary etiquette and culture were mixed with its ambivalent attitude towards music and dance. The tawayaf is a woman who escapes the restricting four-walls of the life of the wife and mother and who has access to education and travel, yet is doomed to live outside of the boundaries of respectability and bourgeois acceptance. In the 2002 remake of the film Devdas, courtesan Madhuri Dixit touches the feet of her lover’s wife, played by Aishwarya Rai, saying she will always look up to the woman who is her moral superior. -

Understanding the Cultural Significance of Tawa'if and Rudali Through the Language of the Body in South Asian Cinema" (2011)

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 Performing Marginal Identities: Understanding the Cultural Significance of awaT 'if and Rudali Through the Language of the Body in South Asian Cinema Lise Danielle Hurlstone Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hurlstone, Lise Danielle, "Performing Marginal Identities: Understanding the Cultural Significance of Tawa'if and Rudali Through the Language of the Body in South Asian Cinema" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 154. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.154 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Performing Marginal Identities: Understanding the Cultural Significance of Tawa‟if and Rudali Through the Language of the Body in South Asian Cinema by Lise Danielle Hurlstone A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Communication Thesis Committee: Priya Kapoor, Chair Charlotte Schell Clare Wilkinson-Weber Portland State University ©2011 Abstract This thesis examines the representation of the lives and performances of tawa‟if and rudali in South Asian cinema to understand their marginalization as performers, and their significance in the collective consciousness of the producers and consumers of Indian cultural artifacts. The critical textual analysis of six South Asian films reveals these women as caste-amorphous within the system of social stratification in India, and therefore captivating in the potential they present to achieve a complex and multi-faceted definition of culture. -

21 Aug Page 07.Qxd

SWAPNIL SANSAR, ENGLISH WEEKLY,LUCKNOW, 28,MARCH, (07) Tragedy Queen of Indian Cinema Contd.From Page no.06 the film's music and lyrics were by Roshan and Sahir to August, Meena Kumari was in the hands of Dr. Sheila Sherlock.Upon Ludhianvi and noted for songs such as "Sansaar Se Bhaage Phirte Ho" and recovery, Meena Kumari returned to India in September 1968 and on the fifth "Mann Re Tu Kaahe". Ghazal directed by Ved-Madan, starring Meena Kumari day after her arrival, Meena Kumari, contrary to doctors' instructionsAAfter their and Sunil Dutt, was a Muslim social film about the right of the young generation marriage, Kamal Amrohi allowed Meena Kumari to continue her actiresumed to the marriage of their choice. It had music by Madan Mohan with lyrics by work. Suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, although Meena Kumari temporarily Sahir Ludhianvi, featuring notable filmi-ghazals such as "Rang Aur Noor Ki recovered but was now much weak and thin. She eventually shifted her focus Baraat", performed by Mohammed Rafi and "Naghma O Sher Ki Saugaat" on more 'acting oriented' or character roles. Out of her last six releases namely performed by Lata Mangeshkar. Main Bhi Ladki Hoon was directed by A. C. Jawab, Saat Phere, Mere Apne, Dushman, Pakeezah & Gomti Ke Kinare, she Tirulokchandar. The film stars Meena Kumari with newcomer Dharmendra. only had a lead role in Pakeezah. In Mere Apne and Gomti Ke Kinare, although Critical acclaim (1962) Sahib Bibi Aur she didn't play a typical heroine role, but her character was actually the central Ghulam (1962) character of the story. -

Bollywood Sounds

Bollywood Sounds Bollywood Sounds The Cosmopolitan Mediations of Hindi Film Song Jayson Beaster-Jones 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beaster-Jones, Jayson. Bollywood sounds : the cosmopolitan mediations of Hindi film song / Jayson Beaster-Jones. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–19–986254–2 (pbk. -

70`S Hits Booklet

70`S HITS - 200 SONGS 14. Yeh Sham Mastani Artiste: Kishore Kumar 01. Chura Liya Hai Tumne Jo Film: Kati Patang Artistes: Asha Bhosle & Mohammed Rafi 15. Bachna Aye Hasinon Film: Yaadon Ki Baaraat Artiste: Kishore Kumar 02. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Film: Hum Kisise Kum Naheen Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & 16. Pyar Diwana Hota Hai Kishore Kumar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Film: Aandhi Film: Kati Patang 03. Do Lafzon Ki Hai Dil Ki Kahani 17. O Saathi Re Artistes: Amitabh Bachchan, Artiste: Kishore Kumar Asha Bhosle & Sharad Kumar Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: The Great Gambler 18. Kya Hua Tera Vada 04. Meet Na Mila Re Man Ka Artistes: Sushma Shrestha & Artiste: Kishore Kumar Mohammed Rafi Film: Abhimaan Film: Hum Kisise Kum Naheen 05. Hum Ne Tum Ko Dekha 19. Tere Mere Milan Ki Yeh Raina Artiste: Shailendra Singh Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Film: Khel Khel Mein Kishore Kumar 06. Bheegi Bheegi Raaton Mein Film: Abhimaan Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & 20. Achha To Hum Chalte Hain Kishore Kumar Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Film: Ajanabee Kishore Kumar 07. Tere Bina Zindagi Se Film: Aan Milo Sajna Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & 21. Tere Chehre Se Nazar Nahin Kishore Kumar Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Film: Aandhi Kishore Kumar 08. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Kabhi Kabhie Artistes: Kishore Kumar & 22. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Film: Ghar Film: Anamika 09. Ab Aan Milo Sajna 23. Maine Tere Liye Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar & Artiste: Mukesh Mohammed Rafi Film: Anand Film: Aan Milo Sajna 24. Bahon Mein Chale Aao 10. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Film: Anamika Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 25. -

Ibombaytalkies – June 13

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Vimi 3 iBombay Talkies Smita Patil 3 VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1 07JUNE, 2013 Geeta Bali 4 GONE TOO SOON... Madhubala 4 Meena Kumari 5 Kuldip Kaur 5 Divya Bharti 6 Caption describing picture or graphic. GONE TOO SOON…! Meena Kumari ‘s rare smile for a camera on the sets of Pakeezah P A G E 3 Unforgettable Movie Stars There is something Madhubala (who other stars, Jiah was about dying young died at 36). Then a budding actress. that perpetuates there is Jiah Khan let’s remember fame. Witness the who committed some of silver icon industry that suicide on Monday screen’s beautiful has sprung around night, all but 25 female stars that Guru Dutt and K.L years old. The ac- managed to make Saigal. Or Meena tual reason behind their mark on soci- Kumari (who Jiah’s death is still ety before their passed at 39) , or unknown. Unlike tragic deaths. MADHUBALA ENJOYING THE GOLDEN ERA OF HINDI FILMS COVER STORY IBOMBAY TALKIES VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1 P A G E 4 Vimi; Wooden Face On Auguest 22, 1977, a d body was wrapped in a soiled dhoti taken to Santa Cruz crematorium on a Chanawalla's thela. It was a last jour- ney of Vimi, a famous film star of late 1960s. There were only a few curious bystanders. Her fans had forgotten her. So had her produc- ers and heroes. "And to imagine that she once used to drive down the same roads in an Impala. Crowds would hope to catch glimpse of the Humraaz heroine. -

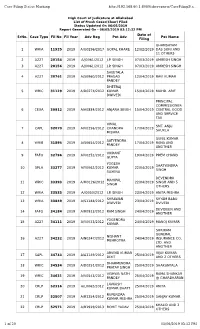

Srno. Case Type Fil No Fil Year Adv Reg Pet Adv Date of Filing Pet

Case Filing Status Marking http://192.168.60.1:8080/ahcrepnew/CaseFilingSta... High Court of Judicature at Allahabad List of Fresh Cases(Clear) Filed Status Updated On 06/05/2019 Report Generated On - 06/05/2019 03:12:32 PM Date of SrNo. Case Type Fil No Fil Year Adv Reg Pet Adv Pet Name Filing GHANSHYAM 1 WRIA 11925 2019 A/G0296/2017 GOPAL KHARE 12/02/2019 DAS SONI AND 11 OTHERS 2 A227 20154 2019 A/J0061/2012 J.P. SINGH 07/03/2019 AMRESH SINGH 3 A227 20156 2019 A/J0061/2012 J.P. SINGH 07/03/2019 AMRESH SINGH SHEETALA 4 A227 30761 2019 A/S0960/2012 PRASAD 12/04/2019 RAVI KUMAR PANDEY DHEERAJ 5 WRIC 31129 2019 A/D0274/2012 KUMAR 15/04/2019 MOHD. ARIF DWIVEDI PRINCIPAL COMMISSIONER 6 CEXA 30912 2019 A/A0884/2012 ANJANA SINGH 15/04/2019 CENTRAL GOOD AND SERVICE TAX VIMAL SMT. ANJU 7 CAPL 32070 2019 A/V0256/2012 CHANDRA 17/04/2019 SHUKLA MISHRA SUNIL KUMAR SATYENDRA 8 WRIB 31895 2019 A/S0654/2012 17/04/2019 RANA AND PANDEY ANOTHER VIKRANT 9 FAFO 32796 2019 A/V0252/2012 19/04/2019 PREM CHAND GUPTA YOGESH SAATYENDRA 10 SPLA 33277 2019 A/Y0062/2012 KUMAR 22/04/2019 SINGH SAXENA DEVENDRA MAHIPAL 11 WRIC 33393 2019 A/M0126/2012 22/04/2019 SINGH AND 5 SINGH OTHERS 12 WRIA 33535 2019 A/I0050/2012 I.P. SINGH 23/04/2019 ANITA MISHRA SHRAWAN SHYAM BABU 13 WRIA 33849 2019 A/S1148/2012 23/04/2019 DWIVEDI DVIVEDI DEVIDEEN AND 14 FAFO 34184 2019 A/R0913/2012 RAM SINGH 24/04/2019 ANOTHER YOGENDRA 15 A227 34111 2019 A/Y0033/2012 24/04/2019 MANOJ KUMAR KUMAR SHRIRAM GENERAL NISHANT 16 A227 34232 2019 A/N0247/2012 24/04/2019 INSURANCE CO. -

Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the 'Muslim' Courtesan (Tawaif) in Hindustani Cinema

DOCTORAL DISSERTATIO Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the ‘Muslim’ Courtesan (tawaif) in Hindustani cinema Farhad Khoyratty Supervised by Dr. Felicity Hand Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Methodology & Literature Review 5 2.1 Methodology 5 2.2 Towards Defining Hindustani Cinema and Bollywood 9 2.3 Gender 23 2.3.1 Feminism: the Three Waves 23 2.4 Feminist Film Theory and Laura Mulvey 30 2.5 Queer Theory and Judith Butler 41 2.6 Discursive Models for the Tawaif 46 2.7 Conclusion 55 3. The Becoming of the Tawaif 59 3.1 The Argument 59 3.2 The Red Dupatta 59 3.3 The Historical Tawaif – the Past’s Present and the Present’s Past 72 3.4 Geisha and Tawaif 91 4. The Courtesan in the Popular Hindustani cinema: Mapping the Ethico-Ideological and Mythopoeic Space She Occupies 103 4.1 The Argument 103 4.2 Mythopoeic Functions of the Tawaif 103 4.3 The ‘Muslim’ Courtesan 120 4.4 Agency of the Tawaif 133 ii 4.5 Conclusion 147 5. Hindustani cinema Herself: the Protean Body of Hindustani cinema 151 5.1 The Argument 151 5.2 Binary Narratives 151 5.3 The Politics of Kissing in Hindustani Cinema 187 5.4 Hindustani Cinema, the Tawaif Who Seeks Respectability 197 Conclusion 209 Bibliography 223 Filmography 249 Webography 257 Photography 261 iii Dedicated to My Late Father Sulliman For his unwavering faith in all my endeavours It is customary to thank one’s supervisor and sadly this has become such an automatic tradition that I am lost for words fit enough to thank Dr. -

Bollywood Films

Libraries BOLLYWOOD FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. Aankhen DVD-5195 Johny Mera Naam DVD-5025 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Junglee DVD-5079 Anand DVD-5044 Lagaan DVD-5073 Aradhana DVD-5033 Love is Life DVD-5158 Baiju Bawra DVD-5387 Madhumati DVD-5171 Bandit Queen DVD-5032 Maine Pyarkiya DVD-5071 Bobby DVD-5176 Marigold DVD-4925 Brave Heart Will Take the Bride DVD-5128 Meaning (Arth) DVD-5035 Bride and Prejudice DVD-4561 Mother India DVD-5072 C.I.D. DVD-5023 Mughal-E-Azam DVD-5040 Chupke Chupke DVD-5152 Naya Daur DVD-5211 Dark Brandon DVD-3176 Om Shanti Om DVD-5088 Deewaar DVD-5174 Paint it Saffron DVD-5046 Destroyed in Love DVD-6845 Pakeezah DVD-5156 Devdas DVD-5167 Parinda DVD-5111 Do Bigha Zamin DVD-5172 Pather Panchali DVD-8571 Garam Hawa DVD-5022 Patiala House DVD-6470 Goddess of Satisfaction DVD-5113 Pyaasa DVD-5041 Guide DVD-5168 Rangeela DVD-8587 Gunga Jumna DVD-5047 Roja DVD-5112 Happiness and Tears DVD-5124 Role DVD-5281 Hare Rama Hare Krishna DVD-5153 Saawariya DVD-3704 Heart is Crazy DVD-2695 Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam DVD-5077 9/5/2017 Satya DVD-4720 DVD-5038 Say You Love Me DVD-5056 Shakespeare Wallah DVD-6476 Sholay DVD-5103 Shree 420 DVD-5155 Silsila DVD-5045 Taal DVD-5175 Tramp (Awara) DVD-5169 Trishul DVD-5092 Two Eyes, Twelve Hands DVD-5102 Umrao Jaan DVD-5090 Upkar DVD-5365 Veer Zaara DVD-5129 Villain DVD-5034 Waqt DVD-5324 What am I to You! DVD-5024 Yaadon Ki Baaraat DVD-5076 You Don't Get to Live Life Twice DVD-7132 Total Titles: 65 Page 2 9/5/2017. -

What Is It Called Good Friday? Joy Ruskin: Agency.On This His Own Sacrifice

WEEKLY www.swapnilsansar.org Simultaneously Published In Hindi Daily & Weekly VOL.23, ISSUE 14, LUCKNOW, 28 MARCH, 2018,PAGE 08,PRICE :1/- What is it called Good Friday? Joy Ruskin: Agency.On this His own sacrifice. But the question is, that if with the Jewish observance of guilt in Jesus; Pilate resolved to day Jesus Christ died on the He was made fun of, insulted Jesus Christ was crucified on this Passover.The etymology of the have Jesus whipped and released term "good" in the context of (Luke 23:3–16). Under the Good Friday is contested. Some guidance of the chief priests, the 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 30th March 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 sources claim it is from the senses crowd asked for Barabbas, who pious, holy of the word "good", had been imprisoned for while others contend that it is a committing murder during an corruption of "God Friday".The insurrection. Pilate asked what Oxford English Dictionary they would have him do with supports the first etymology, Jesus, and they demanded, giving "of a day or season "Crucify him" (Mark 15:6–14). observed as holy by the church" Pilate's wife had seen Jesus in a as an archaic sense of good, and dream earlier that day, and she providing examples of good tide forewarned Pilate to "have meaning "Christmas" or "Shrove nothing to do with this righteous Tues day", and Good Wednesday man" (Matthew 27:19). Pilate had meaning the Wednesday in Jesus flogged and then brought HolyWeek.Conflicting him out to the crowd to release testimony against Jesus was him. -

Last 12 Months Current Affairs, Download Yearly GK PDF (English)

www.gradeup.co w 1 www.gradeup.co Current Affairs Year Book 2018 PDF Dear readers, This PDF is a complete docket of important Current Affairs news and events that occurred in the year 2018. This file is important and relevant for all competitive exams like, SSC, Railways, IB, and other Govt. Exams. Schemes Launched by Union/State Govt. December 1. SC introduced Witness Protection Scheme, 2018 in pilgrimage every year, the expenses for which India will be borne by the government. • The Supreme Court (SC) introduced a witness 3. Jammu & Kashmir Govt. launches AB-PMJAY Scheme protection regime in the country noting that one • Jammu and Kashmir Governor Satya Pal Malik of the main reasons for witnesses turning hostile launched the ambitious “Ayushman Bharat- is that they are not given security by the State. Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY)” • It also announced that the Witness Protection scheme which would benefit over 31 lakh Scheme, 2018 will come into effect immediately residents in the state. across all States. • The governor distributed golden cards among 10 • This scheme is aimed at enabling a witness to eligible beneficiaries for availing the annual depose fearlessly and truthfully, would be the health cover facility, marking the launch of the law of the land till Parliament enacted suitable scheme in the state. legislation. 4. Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana • The Witness Protection Scheme 2018 was • Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana is a framed by the Central government based on the conditional cash transfer scheme for pregnant inputs received from 18 States/Union and lactating women of 19 years of age or above.