Arxiv:2007.11577V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 22 Jul 2020 the Red-Giant Clump (RC), Which Clearly Indicates That in This field There Is a Considerable Amount of Patchy Extinction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfa in the News ~ Week Ending 3 January 2010

Wolbach Library: CfA in the News ~ Week ending 3 January 2010 1. New social science research from G. Sonnert and co-researchers described, Science Letter, p40, Tuesday, January 5, 2010 2. 2009 in science and medicine, ROGER SCHLUETER, Belleville News Democrat (IL), Sunday, January 3, 2010 3. 'Science, celestial bodies have always inspired humankind', Staff Correspondent, Hindu (India), Tuesday, December 29, 2009 4. Why is Carpenter defending scientists?, The Morning Call, Morning Call (Allentown, PA), FIRST ed, pA25, Sunday, December 27, 2009 5. CORRECTIONS, OPINION BY RYAN FINLEY, ARIZONA DAILY STAR, Arizona Daily Star (AZ), FINAL ed, pA2, Saturday, December 19, 2009 6. We see a 'Super-Earth', TOM BEAL; TOM BEAL, ARIZONA DAILY STAR, Arizona Daily Star, (AZ), FINAL ed, pA1, Thursday, December 17, 2009 Record - 1 DIALOG(R) New social science research from G. Sonnert and co-researchers described, Science Letter, p40, Tuesday, January 5, 2010 TEXT: "In this paper we report on testing the 'rolen model' and 'opportunity-structure' hypotheses about the parents whom scientists mentioned as career influencers. According to the role-model hypothesis, the gender match between scientist and influencer is paramount (for example, women scientists would disproportionately often mention their mothers as career influencers)," scientists writing in the journal Social Studies of Science report (see also ). "According to the opportunity-structure hypothesis, the parent's educational level predicts his/her probability of being mentioned as a career influencer (that ism parents with higher educational levels would be more likely to be named). The examination of a sample of American scientists who had received prestigious postdoctoral fellowships resulted in rejecting the role-model hypothesis and corroborating the opportunity-structure hypothesis. -

The Role of Evolutionary Age and Metallicity in the Formation of Classical Be Circumstellar Disks 11

< * - - *" , , Source of Acquisition NASA Goddard Space Flight Center THE ROLE OF EVOLUTIONARY AGE AND METALLICITY IN THE FORMATION OF CLASSICAL BE CIRCUMSTELLAR DISKS 11. ASSESSING THE TRUE NATURE OF CANDIDATE DISK SYSTEMS J.P. WISNIEWSKI"~'~,K.S. BJORKMAN~'~,A.M. MAGALH~ES~",J.E. BJORKMAN~,M.R. MEADE~, & ANTONIOPEREYRA' Draft version November 27, 2006 ABSTRACT Photometric 2-color diagram (2-CD) surveys of young cluster populations have been used to identify populations of B-type stars exhibiting excess Ha emission. The prevalence of these excess emitters, assumed to be "Be stars". has led to the establishment of links between the onset of disk formation in classical Be stars and cluster age and/or metallicity. We have obtained imaging polarization observations of six SMC and six LMC clusters whose candidate Be populations had been previously identified via 2-CDs. The interstellar polarization (ISP). associated with these data has been identified to facilitate an examination of the circumstellar environments of these candidate Be stars via their intrinsic ~olarization signatures, hence determine the true nature of these objects. We determined that the ISP associated with the SMC cluster NGC 330 was characterized by a modified Serkowski law with a A,,, of -4500A, indicating the presence of smaller than average dust grains. The morphology of the ISP associated with the LMC cluster NGC 2100 suggests that its interstellar environment is characterized by a complex magnetic field. Our intrinsic polarization results confirm the suggestion of Wisniewski et al. that a substantial number of bona-fide classical Be stars are present in clusters of age 5-8 Myr. -

Download the 2016 Spring Deep-Sky Challenge

Deep-sky Challenge 2016 Spring Southern Star Party Explore the Local Group Bonnievale, South Africa Hello! And thanks for taking up the challenge at this SSP! The theme for this Challenge is Galaxies of the Local Group. I’ve written up some notes about galaxies & galaxy clusters (pp 3 & 4 of this document). Johan Brink Peter Harvey Late-October is prime time for galaxy viewing, and you’ll be exploring the James Smith best the sky has to offer. All the objects are visible in binoculars, just make sure you’re properly dark adapted to get the best view. Galaxy viewing starts right after sunset, when the centre of our own Milky Way is visible low in the west. The edge of our spiral disk is draped along the horizon, from Carina in the south to Cygnus in the north. As the night progresses the action turns north- and east-ward as Orion rises, drawing the Milky Way up with it. Before daybreak, the Milky Way spans from Perseus and Auriga in the north to Crux in the South. Meanwhile, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds are in pole position for observing. The SMC is perfectly placed at the start of the evening (it culminates at 21:00 on November 30), while the LMC rises throughout the course of the night. Many hundreds of deep-sky objects are on display in the two Clouds, so come prepared! Soon after nightfall, the rich galactic fields of Sculptor and Grus are in view. Gems like Caroline’s Galaxy (NGC 253), the Black-Bottomed Galaxy (NGC 247), the Sculptor Pinwheel (NGC 300), and the String of Pearls (NGC 55) are keen to be viewed. -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

![Arxiv:1802.01597V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 Feb 2018 Born 1991)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6522/arxiv-1802-01597v1-astro-ph-ga-5-feb-2018-born-1991-1726522.webp)

Arxiv:1802.01597V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 Feb 2018 Born 1991)

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. AA_2017_32084 c ESO 2018 February 7, 2018 Mapping the core of the Tarantula Nebula with VLT-MUSE? I. Spectral and nebular content around R136 N. Castro1, P. A. Crowther2, C. J. Evans3, J. Mackey4, N. Castro-Rodriguez5; 6; 7, J. S. Vink8, J. Melnick9 and F. Selman9 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, 1085 S. University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1107, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Hounsfield Road, Sheffield, S3 7RH, UK 3 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK 4 Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 31 Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin, Ireland 5 GRANTECAN S. A., E-38712, Breña Baja, La Palma, Spain 6 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, E-38205 La Laguna, Spain 7 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, E-38205 La Laguna, Spain 8 Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, Northern Ireland, UK 9 European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova 3107, Santiago, Chile February 7, 2018 ABSTRACT We introduce VLT-MUSE observations of the central 20 × 20 (30 × 30 pc) of the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The observations provide an unprecedented spectroscopic census of the massive stars and ionised gas in the vicinity of R136, the young, dense star cluster located in NGC 2070, at the heart of the richest star-forming region in the Local Group. Spectrophotometry and radial-velocity estimates of the nebular gas (superimposed on the stellar spectra) are provided for 2255 point sources extracted from the MUSE datacubes, and we present estimates of stellar radial velocities for 270 early-type stars (finding an average systemic velocity of 271 ± 41 km s−1). -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Dust-Enshrouded Giants in Clusters in the Magellanic Clouds Stellar Dust Emission Are Essential to Measure the Mass-Loss Rate from These Stars

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 3528 July 6, 2018 (DOI: will be inserted by hand later) Dust-enshrouded giants in clusters in the Magellanic Clouds Jacco Th. van Loon1, Jonathan R. Marshall1, Albert A. Zijlstra2 1 Astrophysics Group, School of Physical & Geographical Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK 2 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Sackville Street, P.O.Box 88, Manchester M60 1QD, UK Received date; accepted date Abstract. We present the results of an investigation of post-Main Sequence mass loss from stars in clusters in the Magellanic Clouds, based around an imaging survey in the L′-band (3.8 µm) performed with the VLT at ESO. The data are complemented with JHKs (ESO and 2MASS) and mid-IR photometry (TIMMI2 at ESO, ISOCAM on-board ISO, and data from IRAS and MSX). The goal is to determine the influence of initial metallicity and initial mass on the mass loss and evolution during the latest stages of stellar evolution. Dust-enshrouded giants are identified by their reddened near-IR colours and thermal-IR dust excess emission. Most of these objects are Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) carbon stars in intermediate-age clusters, with progenitor masses between 1.3 and ∼5 M⊙. Red supergiants with circumstellar dust envelopes are found in young clusters, and have progenitor masses between 13 and 20 M⊙. Post-AGB objects (e.g., Planetary Nebulae) and massive stars with detached envelopes and/or hot central stars are found in several clusters. We model the spectral energy distributions of the cluster IR objects, in order to estimate their bolometric luminosities and mass-loss rates. -

The Role of Evolutionary Age and Metallicity in the Formation Of

The Role of Evolutionary Age and Metallicity in the Formation of Classical Be Circumstellar Disks I. New Candidate Be Stars in the LMC, SMC, and Milky Way J.P. Wisniewski1,3 & K.S. Bjorkman2,3 ABSTRACT We present B, V, R, and Hα photometry of 8 clusters in the Small Magellanic Cloud, 5 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, and 3 Galactic clusters, and use 2 color diagrams (2-CDs) to identify candidate Be star populations in these clusters. We find evidence that the Be phenomenon is enhanced in low metallicity environ- ments, based on the observed fractional early-type candidate Be star content of clusters of age 10-25 Myr. Numerous candidate Be stars of spectral types B0 to B5 were identified in clusters of age 5-8 Myr, challenging the suggestion of Fab- regat & Torrejon (2000) that classical Be stars should only be found in clusters at least 10 Myr old. These results suggest that a significant number of B-type stars must emerge onto the zero-age-main-sequence as rapid rotators. We also detect an enhancement in the fractional content of early-type candidate Be stars in clusters of age 10-25 Myr, suggesting that the Be phenomenon does become more prevalent with evolutionary age. We briefly discuss the mechanisms which might contribute to such an evolutionary effect. A discussion of the limitations of utilizing the 2-CD technique to investigate the role evolutionary age and/or metallicity play in the development of the Be phenomenon is offered, and we provide evidence that other B-type objects of very different nature, such as can- didate Herbig Ae/Be stars may contaminate the claimed detections of “Be stars” arXiv:astro-ph/0606525v1 21 Jun 2006 via 2-CDs. -

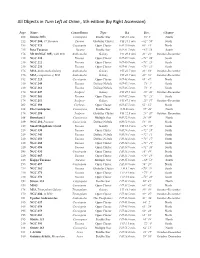

All Objects by Right Ascension For

All Objects in Turn Left at Orion , 5th edition (by Right Ascension) Page Name Constellation Type RA Dec. Chapter 188 Struve 3053 Cassiopeia Double Star 0 H 2.6 min. 66° 6' North 212 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Tucana Globular Cluster 0 H 24.1 min −62° 58' South 193 NGC 129 Cassiopeia Open Cluster 0 H 29.8 min. 60° 14' North 215 Beta Tucanae Tucana Double Star 0 H 31.5 min. −62° 58' South 176 M110 (NGC 205), with M31 Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 40.3 min 41° 41' October–December 210 NGC 220 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' South 210 NGC 222 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' South 210 NGC 231 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' South 176 M31, Andromeda Galaxy Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 42.7 min 41° 16' October–December 176 M32, companion of M31 Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 42.7 min 40° 52' October–December 192 NGC 225 Cassiopeia Open Cluster 0 H 43.4 min. 61° 47' North 210 NGC 249 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 45.5 min. −73° 5' South 210 NGC 261 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 46.5 min. −73° 6' South 174 NGC 247 Sculptor Galaxy 0 H 47.1 min −20° 46' October–December 210 NGC 265 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' South 174 NGC 253 Sculptor Galaxy 0 H 47.5 min −25° 17' October–December 202 NGC 188 Cepheus Open Cluster 0 H 47.5 min. -

Stars, Galaxies, and Beyond, 2012

Stars, Galaxies, and Beyond Summary of notes and materials related to University of Washington astronomy courses: ASTR 322 The Contents of Our Galaxy (Winter 2012, Professor Paula Szkody=PXS) & ASTR 323 Extragalactic Astronomy And Cosmology (Spring 2012, Professor Željko Ivezić=ZXI). Summary by Michael C. McGoodwin=MCM. Content last updated 6/29/2012 Rotated image of the Whirlpool Galaxy M51 (NGC 5194)1 from Hubble Space Telescope HST, with Companion Galaxy NGC 5195 (upper left), located in constellation Canes Venatici, January 2005. Galaxy is at 9.6 Megaparsec (Mpc)= 31.3x106 ly, width 9.6 arcmin, area ~27 square kiloparsecs (kpc2) 1 NGC = New General Catalog, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_General_Catalogue 2 http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2005/12/image/a/ Page 1 of 249 Astrophysics_ASTR322_323_MCM_2012.docx 29 Jun 2012 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Useful Symbols, Abbreviations and Web Links .................................................................................................................. 4 Basic Physical Quantities for the Sun and the Earth ........................................................................................................ 6 Basic Astronomical Terms, Concepts, and Tools (Chapter 1) ............................................................................................. 9 Distance Measures ...................................................................................................................................................... -

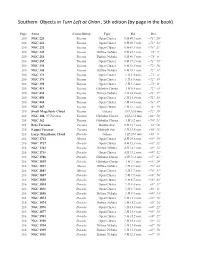

Southern Objects Paging

Southern Objects in Turn Left at Orion , 5th edition (by page in the book) Page Name Constellation Type RA Dec. 210 NGC 220 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' 210 NGC 222 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' 210 NGC 231 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' 210 NGC 249 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 45.5 min. −73° 5' 210 NGC 261 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 46.5 min. −73° 6' 210 NGC 265 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' 210 NGC 330 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 56.3 min. −72° 28' 210 NGC 346 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 59.1 min. −72° 11' 210 NGC 371 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.4 min. −72° 4' 210 NGC 376 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.9 min. −72° 49' 210 NGC 395 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 5.1 min. −72° 0' 210 NGC 419 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 8.3 min −72° 53' 210 NGC 456 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 1 H 14.4 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 458 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.9 min. −71° 33' 210 NGC 460 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.6 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 465 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 15.7 min. −73° 19' 210 Small Magellanic Cloud Tucana Galaxy 0 H 53.0 min −72° 50' 212 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Tucana Globular Cluster 0 H 24.1 min −62° 58' 214 NGC 362 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 3.2 min −70° 51' 215 Beta Tucanae Tucana Double Star 0 H 31.5 min. -

Astronomy an Overview

Astronomy An overview PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 13 Mar 2011 01:29:56 UTC Contents Articles Main article 1 Astronomy 1 History 18 History of astronomy 18 Archaeoastronomy 30 Observational astronomy 56 Observational astronomy 56 Radio astronomy 61 Infrared astronomy 66 Visible-light astronomy 69 Ultraviolet astronomy 69 X-ray astronomy 70 Gamma-ray astronomy 86 Astrometry 90 Celestial mechanics 93 Specific subfields of astronomy 99 Sun 99 Planetary science 123 Planetary geology 129 Star 130 Galactic astronomy 155 Extragalactic astronomy 156 Physical cosmology 157 Amateur astronomy 164 Amateur astronomy 164 The International Year of Astronomy 2009 170 International Year of Astronomy 170 References Article Sources and Contributors 177 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 181 Article Licenses License 184 1 Main article Astronomy Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects (such as stars, planets, comets, nebulae, star clusters and galaxies) and phenomena that originate outside the Earth's atmosphere (such as the cosmic background radiation). It is concerned with the evolution, physics, chemistry, meteorology, and motion of celestial objects, as well as the formation and development of the universe. Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences. Prehistoric cultures left behind astronomical artifacts such as the Egyptian monuments and Stonehenge, and early civilizations such as the Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, Indians, and Maya performed methodical observations of the night sky. However, the invention of the telescope was required before astronomy was able to develop into a modern science. Historically, astronomy A giant Hubble mosaic of the Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant has included disciplines as diverse as astrometry, celestial navigation, observational astronomy, the making of calendars, and even astrology, but professional astronomy is nowadays often considered to be synonymous with astrophysics.