The Intersectionality of Precarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living on the Edge: Delineating the Political Economy of Precarity In

Living on the Edge: Delineating the Political Economy of Precarity in Vancouver, Canada Robert Catherall School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia ABSTRACT Canadian cities are in the midst of a housing crisis, with Vancouver as their poster-child. The city’s over- inflated housing prices decoupled from wages in the early aughts, giving rise to a seller’s rental market and destabilizing employment. As neoliberal policies continue to erode the post-war welfare state, an increasing number of Canadians are living in precarious environments. This uncertainty is not just applicable to housing, however. Employment tenure has been on the decline, specifically since 2008, and better jobs—both in security and quality of work, with more equitable wages—are becoming less and less common. These elements of precarity are making decent work (as defined by the ILO), security of housing tenure, and a right to the city some of the most pressing issues at hand for Canadians. Using Vancouver as the principal case study, the political economy of precarity is examined through the various facets—including socio-cultural, economic, health, and legal—that are working to normalize this inequity. This paper proceeds to examine the standard employment relationship (SER) in a Canadian context through a critique of the neoliberal policies responsible for eroding the once widely-implemented SER is provided to conclude the systemic marginalization experienced by those in precarious and informal situations must be addressed via public policy instruments and community-based organization. INTRODUCTION While the sharing economy, such as shared housing provider Airbnb, or the gig economy associated with organizations like Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, and Fiverr, conjure images of affordable options for travellers, or employment opportunities during an economic downturn, they have simultaneously normalized housing crises and stagnating wages for those who live and work in urban centres. -

The Struggles of Iregularly-Employed Workers in South Korea, 1999-20121

1 The Struggles of Iregularly-Employed Workers in South Korea, 1999-20121 Jennifer Jihye Chun Department of Sociology University of Toronto [email protected] November 25, 2013 In December 1999, two years after the South Korean government accepted a $58.4 billion bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), President Kim Dae-Jung announced that the nation’s currency crisis was officially over. The South Korean government’s aggressive measures to stabilize financial markets, which included drastic efforts to reduce labor costs, dismantle employment security, and legalize indirect forms of dispatch or temporary employment, contributed to the fastest recovery of a single country after the 1997 Asian Debt Crisis, restoring annual GDP growth rates to pre-crisis levels.2 While the business community praised such efforts for helping debt-ridden banks and companies survive the crisis, labor unions and other proponents of social and economic justice virulently condemned the government’s neoliberal policy agenda for subjecting workers to deepening inequality and injustice. Despite differing opinions on the impact of government austerity measures, both sides agree that the “post-IMF” era is synonymous with a new world of work. Employment precarity – that is, the vulnerability of workers to an array of cost-cutting employer practices that depress wage standards, working conditions and job and income security – is a defining feature of the 21st century South Korean economy. The majority of jobs in the labor market consist of informal and precarious jobs that provide minimal, if any, legal protection against unjust and discriminatory employment practices. Informally- and precariously- employed workers also face numerous barriers to challenging deteriorating working conditions and heightened employer abuses through the conventional repertoire of unionism: strikes, collective bargaining and union agreements. -

The Hidden Work of Challenging Precarity

THE HIDDEN WORK OF CHALLENGING PRECARITY KIRAN MIRCHANDANI MARY JEAN HANDE Abstract. This article explores the hidden work of workers employed in pre- carious jobs which are characterized by part-time and temporary contracts, limited control over work schedules, and poor access to regulatory protection. Through 77 semi-structured interviews with workers in low-wage, precarious jobs in Ontario, Canada, we examine workers’ attempts to challenge the precar- ity they face when confronted by workplace conditions violating the Ontario Employment Standards Act (ESA), such as not being paid minimum wages, not being paid for overtime, being fired wrongfully or being subject to reprisals. We argue that these challenges involve hidden work, which is neither acknowledged nor recognized in the current ESA enforcement regime. We examine three types of hidden work that involve (1) creating a sense of positive self-worth amidst disempowering practices; (2) engaging in advocacy vis-à-vis employers, some- times through launching official claims with the Ontario Ministry of Labour; and (3) developing strategies to avoid the costs of job precarity in the future. We show that this hidden work of challenging job precarity needs to be formally recognized and that concrete strategies for doing so would lead to more robust protection for workers, particularly within ESA enforcement practices. Keywords: Hidden Work, Employment Relationships, Employment Standards, Low-wage work, Precarity, Stratification. Résumé. Cet article explore le travail caché de ceux qui occupent des emplois précaires se caractérisant par des contrats à temps partiel et temporaires, un con- trôle limité de leurs horaires de travail et des lacunes en matière de protection réglementaire. -

Precarity: a Savage Journey to the Heart of Embodied Capitalism

10 2006 Precarity: A Savage Journey to the Heart of Embodied Capitalism Vassilis Tsianos / Dimitris Papadopoulos A. Introduction There is an underlying assumption to the current debates about class composition in post-Fordism: this is the assumption that immaterial work and its corresponding social subjects form the centre of gravity in the new turbulent cycles of struggles around living labour. This paper explores the theoretical and political implications of this assumption, its promises and closures. Is immaterial labour the condition out of which a radical socio-political transformation of contemporary post-Fordist capitalism can emerge? Who’s afraid of immaterial workers today? B. Immaterial labour and precarity In their attempt to historicize the emergence of the concept of the general intellect, many theorists (e.g. Hardt & Negri, 2000; Virno, 2004) remind us that the general intellect cannot be conceived simply as a sociological category. We think that we should apply the same precaution when using the concept of immaterial labour. This is the case especially when the studies which acknowledge the sociological evidence of immaterial work are increasing, such as research in the mainstream sociology of work which investigates atypical employment and the subjectivisation of labour (e.g. Lohr & Nickel, 2005; Moldaschl & Voss, 2003), or even conceptualisations of immaterial labour in the context of knowledge society (e.g. Gorz, 2004). A mere sociological understanding of the figure of immaterial labour is restricted to a simplistic description of the spreading of features such as affective labour, networking, collaboration, knowledge economy etc. into what mainstream sociology calls network society (Castells, 1996). What differentiates a mere sociological description from an operative political conceptualisation of immaterial labour – which is situated in co-research and political activism (Negri, 2006) – is the quest for understanding the power dynamics of living labour in post-Fordist societies. -

For the Global Emancipation of Labour: New Movements and Struggles Around Work, Workers and Precarity

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Call for papers Volume 3 (2): 478 - 481 (November 2011) Vol 4 (2): global emancipation of labour Call for papers vol 4 issue 2 (November 2012) For the global emancipation of labour: new movements and struggles around work, workers and precarity Issue editors: Alice Mattoni, Elizabeth Humphrys, Peter Waterman, Ana Margarida Esteves Once, the labour movement was seen as the international social movement for the left (and it was the spectre haunting capitalism). Over the last century, however, labour movements have been transformed. In most of the world membership rates have dwindled, and many act in defence of, or simply provide services to, their members in the spirit of interest or lobbying groups. Labour was once a broad social movement including cooperatives, socialist parties, women’s and youth wings, press and publications, cultural production and sporting clubs. Often it was at the core of movements for democracy or national independence, even of social revolution. Despite the rhetoric of “socialism”, “class and mass trade unionism” or, alternatively, technocratic “organising strategies”, most union movements internationally operate strictly within the parameters of capitalism and the ideology of “social partnership” (i.e. with and under capital and state). New labour organising efforts are increasingly moving beyond traditional trade union forms, dependence on the state or parties of the left, and have found new forms linked to ethnic or geographical communities, working women, precarious workers, migrants and other radical-democratic social movements. These changes may relate to the neoliberalisation and “globalization” of capitalism, and its result in restructured industry and employment. -

Segmentation, Fragmentation and Transnational Migrant Labour In

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF EVERYDAY PRECARITY : SEGMENTATION , FRAGMENTATION AND TRANSNATIONAL MIGRANT LABOUR IN CALIFORNIAN AGRICULTURE A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 FABIOLA MIERES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES /P OLITICS LIST OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................... 7 DECLARATION ................................................................................................................................... 8 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ................................................................................................................... 9 DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................................... 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................... 10 THE AUTHOR ................................................................................................................................... 11 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION: LICENCE TO EXPLOIT? NEW INSIGHTS INTO MEXICAN MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES ................................................................................................................................ 15 Background -

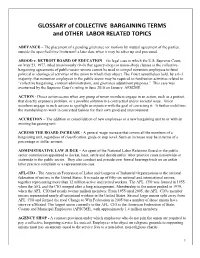

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS ABEYANCE – The placement of a pending grievance (or motion) by mutual agreement of the parties, outside the specified time limits until a later date when it may be taken up and processed. ABOOD v. DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION – The legal case in which the U.S. Supreme Court, on May 23, 1977, ruled unanimously (9–0) that agency-shop (or union-shop) clauses in the collective- bargaining agreements of public-sector unions cannot be used to compel nonunion employees to fund political or ideological activities of the union to which they object. The Court nevertheless held, by a 6–3 majority, that nonunion employees in the public sector may be required to fund union activities related to “collective bargaining, contract administration, and grievance adjustment purposes.” This case was overturned by the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2018 on Janus v. AFSCME. ACTION - Direct action occurs when any group of union members engage in an action, such as a protest, that directly exposes a problem, or a possible solution to a contractual and/or societal issue. Union members engage in such actions to spotlight an injustice with the goal of correcting it. It further mobilizes the membership to work in concerted fashion for their own good and improvement. ACCRETION – The addition or consolidation of new employees or a new bargaining unit to or with an existing bargaining unit. ACROSS THE BOARD INCREASE - A general wage increase that covers all the members of a bargaining unit, regardless of classification, grade or step level. -

The Perceived Precarity and Identity of Australian Journalists

Asia Pacific Refereed Paper Journal of Arts & Cultural From Battery Hens to Chicken Feed: The Perceived Management Precarity and Identity of Australian Journalists Authors: Holly Patrick and Kate Elks Abstract There is an industrial revolution taking place in the media sphere, and it is a result of digitalisation. Between mass layoffs and falling word rates, Australian journalists are exposed to multiple potential sources of precarity. This paper makes use of a case study of Australian journalists to explore the perceived causes and experiences of precarity for journalists working across the media industries. We find that the perceptions of precarity for salaried journalists are different from those of freelancers. We also find that not all of our journalist participants consider their work to be precarious, but that these perceptions are shaped by their professional identities. We contribute to the literature on employment precarity by identifying an unexplored role that preferred professional identities may play in enabling and limiting career mobility, and therefore in contributing to perceptions of precarity. Keywords Precarity; Professional Identity; Journalism; Cultural Work; Digitalisation Biography Holly Patrick wrote this article during a 2 year tenure as a visiting scholar with the Centre for Management and Organisation studies at UTS Business School in Sydney, Australia. As of January 2016 she will be joining the University of Edinburgh Napier as Lecturer in HRM. Kate Elks is a content marketer and former journalist. She wrote this article while working as content director for Sydney agency Filtered Media, to better understand the pressures and opportunities facing media practitioners. Contact: [email protected] The Asia Pacific Journal of Arts and Cultural Management is available at: apjacm.arts.unimelb.edu.au and is produced by the School of Culture and Communication: www.culture-communication.unimelb.edu.au at the University of Melbourne: www.unimelb.edu.au 48 Asia Pacific Journal of Arts and Cultural Management Vol. -

Precarity, Populism and Walling in a ‘European’ Refugee Crisis

Impossible Landings: Precarity, Populism and Walling in a ‘European’ Refugee Crisis By Alessandro Tiberio A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Watts, Co-Chair Professor Jon Kosek, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes Professor Cristiana Giordano Professor Jovan Lewis Summer 2018 Impossible Landings: Precarity, Populism and Walling in a ‘European’ Refugee Crisis © 2018 Alessandro Tiberio 1 Abstract Impossible Landings: Precarity, Populism and Walling in a ‘European’ Refugee Crisis by Alessandro Tiberio Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Watts, Co-Chair Professor Jon Kosek, Co-Chair The rise of populist movements that gathered momentum in 2016 across Europe and the European settler-colonial world has seriously challenged the US-led neoliberal order as much as the discourse around ‘globalization’ that such order promoted and defended. Such crisis has been most striking in countries like the UK and the US, with the votes for Brexit and Trump, given that for the last 30 years successive government administrations of both center-right and center-left political alignments there have been championing neoliberal reforms domestically and internationally, but the rise of populist movements has been years in the making in the folds of ordinary life across the ‘European’ world, and can arguably be best understood through an ethnographic research of the everyday space-making and border-renegotiating social processes that made a rightward shift possible in individual and collective consciences and that also allowed it to gather momentum at a wider scale. -

Policies and Regulation to Combat Precarious Employmentpdf

POLICIES AND REGULATIONS TO COMBAT PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT ACTRAV | POLICIES AND REGULATIONS TO COMBAT PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT Copyright © International Labour Organization 2011 First published 2011 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data From precarious work to decent work. Policies and regulations to combat precarious employment 978-92-2-125522-2 (print), 978-92-2-125523-9 (web pdf) Also available in French: Du travail précaire au travail décent. Politiques et règlementation visant à lutter contre l'emploi précaire (ISBN 978-92-2-225522-1 (print), 978-92-2-225523-8 (web pdf)), Geneva, 2011, in Spanish: Del trabajo precario al trabajo decente. Políticas y reglamentación para luchar contra el empleo precario (ISBN 978-92-2-325522-0 (print), 978-92-2-325523-7 (web pdf)), Geneva, 2011. The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

A Place and Space for a Critical Geography of Precarity?

This is a repository copy of A place and space for a critical geography of precarity?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/81294/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Waite, L (2009) A place and space for a critical geography of precarity? Geography Compass, 3 (1). 412 - 433 (21). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00184.x Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ A place and space for a critical geography of precarity? Louise Waite School of Geography University of Leeds Woodhouse Lane Leeds LS2 9JT UK Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract This paper explores growing interest in the term ‘precarity’ within the social sciences and asks whether there is a place for a ‘critical geography of precarity’ amidst this emerging field. -

The Union Is the Message: Messenger Work and Messenger Organizing in the Same-Day Courier Sector David 0

The Union is the Message: Messenger Work and Messenger Organizing in the Same-Day Courier Sector David 0. Lavin A Dissertation* submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy* Graduate Program in Sociology, York University Toronto, Ontario August 2013 ©David 0. Lavin, 2013 ii Abstract Work in the same-day courier sector is a precarious form of employment. Workers in this sector are also treated as self-employed and hired as independent contractors. The relationship with the firm for which they work, however, is hardly distinguishable from an employment relationship. Messengers are among a growing number of workers in Canada who can be labeled as disguised employees. To explore the phenomenon of disguised employment, I use a case study approach informed by critical political economic theory and a purposive approach to labour and employment law to examine work in the same-day courier sector in Toronto with a focus on a subpopulation of workers in this sector: bike messengers. I examine the causes and consequences of self-employment in the same-day courier sector, analyze messengers' work and argue that their employment status entails misclassification. In an increasingly market-mediated society we are witnessing a proliferation of unprotected work relationships with disguised employment being one manifestation of this development. Fortunately, some unions are trying to organize workers in disguised employment relationships. In this dissertation, I also examine an attempt by the Canadian Union of Postal Workers to organize workers in Toronto's same-day courier sector. I explore the processes and implications of organizing disguised employees and examine how organizing these workers relates to and can inform the project of union renewal in Canada.