Griffith Business School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Drives Response QI Results S Group More Than How TV Ads Work with Other Media L Result RT Doublesd Its Operating

6 May 2010 week 18 : TV drives response QI Results s Group more than How TV ads work with other media L result RT doublesd its operating France United Kingdom Groupe M6 publishes Q1 Five is giving away a role revenues in Neighbours Germany Greece IP Deutschland celebrates Alpha TV broadcasts 50th anniversary Greek Idol week 18 the RTL Group intranet 6 May 2010 week 18 Cover: Montage showing direct response to a TV spot via internet : TV drives response QI Results s Group more than How TV ads work with other media L result RT 2 doublesd its operating France United Kingdom Groupe M6 publishes Q1 Five is giving away a role revenues in Neighbours Germany Greece IP Deutschland celebrates Alpha TV broadcasts 50th anniversary Greek Idol week 18 the RTL Group intranet “TV advertising makes things happen” Direct Response is one of the most underestimated effects of TV advertising. Tess Alps explains. Tess Alps, CEO of Thinkbox United Kingdom - 6 May 2010 On this year’s TV Wirkungstag (TV Effective- the IPA (Institute of Practitioners in Advertising) ness Day) in Frankfurt am Main, Tess Alps, in the UK – which prove that campaigns which CEO of Thinkbox, presented a study investigat- include TV deliver better ROI and business ing response driven by TV advertising. Online, success than those which do not include TV. click-through rates let advertisers know whether their ad is working or not – although Alps was We know much more these days – from careful to point out that “accountability, or bet- neuroscience and psychology – about why TV ter ‘countability’, is not the same as effective- advertising works so well and how the human ness.” On television, such direct feedback is not brain responds to it. -

Un Film Di Josie Rourke

! Un film di Josie Rourke Durata: 2 ore 3 minuti !1 ! CAST Maria Stuarda / Saoirse Ronan Elisabetta I / Margot Robbie Lord Darnley / Jack Lowden Robert Dudley / Joe Alwyn John Knox / David Tennant Sir William Cecil / Guy Pearce Duchessa di Hardwick / Gemma Chan Conte di Bothwell / Martin Compston Rizzio / Ismael Cruz Cordova Conte di Lennox / Brendan Coyle Lord Maitland / Ian Hart Lord Randolph / Adrian Lester Conte di Moray / James McArdle AUTORI DEL FILM Regista / Josie Rourke Scritto da Beau Willimon Basato sul libro “Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart” di John Guy Produttori / Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward Direttore della Fotografia / John Mathieson Scenografie / James Merifield Costumi / Alexandra Byrne Trucco e Acconciature / Jenny Shircore !2 Montaggio / Chris Dickens Musiche / Max Richter !3 ! Sommario I. Sinossi . 4 II. Cronologia dei Fatti. 6 III. Un esempio storico per le donne di potere nel mondo moderno. 7 IV. La scelta del cast: dare vita alla storia. 12 V. L’incontro delle Regine. 21 VI. La Produzione . 24 VII. Guardaroba e Parrucche: fra capelli e acconciature 30 VIII. Il Cast . 34 IX. Gli autori del Film . 45 X. Crediti . 51 !4 SINOSSI BREVE MARIA REGINA DI SCOZIA – MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS è il racconto della turbolenta vita di Maria Stewart (Saoirse Ronan), basato sul libro “Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart” dello storico John Guy. Regina di Francia a 16 anni, già vedova a 18, Maria respinge le pressioni che la vorrebbero vedere risposata e decide di tornare nella natia Scozia per riprendere la corona che le spetta di diritto. -

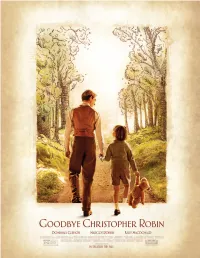

Production-Notes-Photos-Image-For

2 GOODBYE CHRISTOPHER ROBIN gives a rare glimpse into the relationship between beloved children's author A. A. Milne (Domhnall Gleeson) and his son Christo- pher Robin (Will Tilston), whose toys inspired the magical world of Winnie the Pooh. Along with his mother Daphne (Margot Robbie), and his nanny Olive (Kelly Macdonald), Christopher Robin and his family are swept up in the international success of the books; the enchanting tales bringing hope and comfort to England after the First World War. But with the eyes of the world on Christopher Robin, what will the cost be to the family? GOODBYE CHRISTOPHER ROBIN stars Domhnall Gleeson (THE REVENANT, STAR WARS: THE FORCE AWAKENS), Margot Robbie (SUICIDE SQUAD, THE WOLF OF WALL STREET), Kelly Macdonald (SWALLOWS AND AMAZONS, “Boardwalk Empire”), Alex Law- ther (THE IMITATION GAME) and introducing Will Tilston. The cast also includes Stephen Campbell Moore (SEASON OF THE WITCH), Vicki Pepperdine (MY COUSIN RACHEL), Rich- ard McCabe (CINDERELLA), Geraldine Somerville (MY WEEK WITH MARILYN) and Phoebe Waller-Bridge (THE IRON LADY). Directed by Simon Curtis (WOMAN IN GOLD, MY WEEK WITH MARILYN) from a script written by Frank Cottrell-Boyce (THE RAILWAY MAN, MILLIONS) and Simon Vaughan (“War and Peace,” “Ripper Street”), the film producers are Damian Jones, p.g.a. (ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS: THE MOVIE, THE LADY IN THE VAN) and Steve Christian, p.g.a. (BELLE, THETHE LIBERTINE)LIBERTINE) withwith Curtis Curtis and and Vaughan Vaughan serves serving as executiveas executive producer producers and Mark and HubbardMark Hubbard as co-producer as co-producer (ABSOLUTELY (ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS: FABULOUS: THE MOVIE). -

Deutscher Kinostart: 22. März 2018

präsentiert Deutscher Kinostart: 22. März 2018 www.PeterHaseFilm.de In PETER HASE™ übernimmt der schelmische und abenteuerlustige Titelheld, der bereits Generationen von Kindern und Erwachsenen auf der ganzen Welt begeistert hat, die Hauptrolle in seiner eigenen, modernen Komödie. Peters Kleinkrieg mit Mr. McGregor erreicht im Film bisher ungeahnte Ausmaße, als beide versuchen, die Kontrolle über den umhegten Gemüsegarten von McGregor zu gewinnen. Außerdem konkurrieren sie um die Zuneigung der warmherzigen und tierlieben Nachbarin. Dabei verschlägt es die beiden vom malerischen Lake District bis mitten hinein ins geschäftige London. Will Gluck führte Regie, basierend auf einer Geschichte für die Leinwand und einem Drehbuch von Rob Lieber und ihm selbst. Der Film basiert auf den Figuren aus den Geschichten von Peter Hase von Beatrix Potter. Produzenten sind Will Gluck und Zareh Nalbandian. Doug Belgrad, Jodi Hildebrand und Jason Lust fungieren als Executive Producers. PETER HASE™ erscheint im Verleih von Sony Pictures Releasing International und wird von Columbia Pictures und Sony Pictures Animation präsentiert. Der Film ist eine Produktion von 2.0 ENTERTAINMENT und Animal Logic Entertainment und Olive Bridge Entertainment. In der deutschen Fassung sind Christoph Maria Herbst als „Peter Hase“, Heike Makatsch als „Flopsi“, Jessica Schwarz als „Mopsi“ und Anja Kling als „Wuschelpuschel“ zu hören. PETER HASE™ sowie alle zugehörigen Figuren: ™ & © Frederick Warne & Co Limited. Deutscher Kinostart: 22. März 2018 www.PeterHaseFilm.de www.Facebook.com/PeterHaseFilm bit.ly/2AXWfT9 www.YouTube.com/SonyPicturesGermany www.Twitter.com/SonyPicturesDE www.Instagram.com/SonyPictures.DE #PeterHaseFilm 2 PETER HASE™ sowie alle zugehörigen Figuren: ™ & © Frederick Warne & Co Limited. PRODUCTION NOTES “When I was a kid, my dad read me the Peter Rabbit books, so I always had an emotional tie to him – and when I had kids, I read the books to them,” says Will Gluck, the co-writer/director of the famous bunny’s first big screen adventure, Peter Rabbit. -

In Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino Continues to Evolve and to Surprise Audiences

“ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD” Preliminary Production Information With Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino continues to evolve and to surprise audiences. While the movie has all of the hallmarks of a Tarantino film – a wholly original story, with fresh characters, presented with bravura technique – his ninth film also breaks new ground for the writer-director. It is a character-driven story, dealing with mature issues of unfulfilled expectations that inevitably confront us all as we age. In Hollywood, this struggle is particularly dramatic, as success and failure live side by side. In Once Upon a Time…, they do so literally as well as figuratively. Uniting two of today’s greatest stars in a first-ever pairing and recreating an entire lost era, the film is big cinema made for the big screen. A true original in a landscape of sequels and superheroes. Set in 1969, Tarantino recreates the time and place of his formative years, when everything – the United States, the city of Los Angeles, the Hollywood star system, even the movies themselves – was at an inflection point, and no one knew where the pieces would land. All this is not entirely dissimilar from the changes buffeting Hollywood today. At the center is Rick Dalton, played by Leonardo DiCaprio. Rick had been the star of “Bounty Law,” a hit television series in the 50s and early 60s, but his prophesied transition to motion picture stardom never materialized. Now, as Hollywood moves towards a hippie aesthetic, Rick worries that his time has passed – and wonders if there’s still a chance for him. -

Le Casting Du Film : Donner Vie À L’Histoire

UNIVERSAL PICTURES présente en association avec PERFECT WORLD PICTURES une production WORKING TITLE (MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS) Réalisé par JOSIE ROURKE Avec SAOIRSE RONAN MARGOT ROBBIE JACK LOWDEN JOE ALWYN Scénario de BEAU WILLIMON Produit par TIM BEVAN, ERIC FELLNER, DEBRA HAYWARD D’après le livre “Queen of Scots : The True Life of Mary Stuart”de DR. JOHN GUY SORTIE LE 27 FÉVRIER 2019 Durée : 2h04 Matériel disponible sur www.upimedia.com MarieStuart-lefi lm.com / FocusFeaturesFR /UniversalFr #MarieStuart DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Universal Pictures International Sylvie FORESTIER 21, rue François 1er - 75008 Paris Giulia GIÉ Tél. : 01 40 69 66 56 assistées de Sophie GRECH www.universalpictures.fr Synopsis MARIE STUART, REINE D’ÉCOSSE est une version nouvelle de la vie tumultueuse de Marie Stuart (Saoirse Ronan) d’après le livre « Queen of Scots : The True Life of Marie Stuart » de John Guy. Reine de France à 16 ans, veuve à 18, Marie défie ceux qui la pressent de se remarier. Elle préfère retourner dans son Écosse natale pour revendiquer le trône qui lui revient de droit. Par sa naissance, Marie peut aussi prétendre à la couronne d’Élisabeth (Margot Robbie), reine d’Angleterre. À l’opposé des précédentes incarnations du personnage et en s’appuyant sur les recherches de John Guy, Marie nous apparaît ici comme une femme de pouvoir, habile en politique, qui souhaite faire alliance avec sa cousine Élisabeth. Elle se bat pour imposer son autorité dans un royaume indocile, à une époque où les femmes monarques sont considérées comme des monstres. Pour assurer chacune leur légitimité, les deux reines font des choix opposés en matière de mariage et de descendance. -

Questione Di Tempo

QUESTIONE DI TEMPO Note di produzione Per più di tre decenni, il regista RICHARD CURTIS ha creato la sua impronta personale nel modo della cinematografia e della televisione, mettendo in scena personaggi indimenticabili che in modo alterno ci hanno permesso di ridere delle manie umane e di condividere commoventi lacrime nel viaggio straordinario che accompagna le nostre vite ordinarie. Curtis ha cominciato ad affinare la sua voce come scrittore di show televisivi classici come Not the Nine O’Clock News, Blackadder, Mr Bean e The Vicar of Dibley. Quando si è spostato al grande schermo, ha piacevolmente sorpreso il pubblico di tutto il mondo con le sceneggiature di tenere e commoventi commedie, ormai diventate dei classici, come Quattro matrimoni e un funerale, Notting Hill e Il diario di Bridget Jones. Questa esperienza ha preparato la strada al suo debutto alla regia, il blockbuster globale Love Actually – L’amore davvero, seguito dalla sua dichiarazione d’amore alla musica pop degli anni ’60, I love Radio Rock, che ha anche diretto. Ora, con Questione di tempo, Curtis ci dona il suo film più intimo e personale. All’età di 21 anni, Tim Lake (DOMHNALL GLEESON di Anna Karenina, Harry Potter e i doni della morte: Parte 2) scopre di poter viaggiare nel tempo… La sera dopo l’ennesima insoddisfacente festa di Capodanno, il padre di Tim (BILL NIGHY di Marigold Hotel, Love Actually – L’amore davvero) dice a suo figlio che gli uomini della sua famiglia hanno sempre avuto la capacità di viaggiare nel tempo. Tim non potrà cambiare la storia, ma può cambiare quello che accade ed è accaduto nella sua vita, ed è per qesto che decide di rendere il mondo un posto migliore trovandosi una ragazza.