Via Issuelab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin #26 June 30, 2018

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #26 June 30, 2018 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, June 30, 2018 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (Legislation was signed by Council President Shannon Hardin on the night of the Council meeting, Monday, June 25, 2018; Ordinances 1633-2018 and 1637-2018 were returned unsigned by Mayor Andrew J. Ginther on Tuesday, June 26, 2018; Mayor Ginther signed all of the other legislation on Wednesday, June 27, 2018; All of the legislation included in this edition was attested by the City Clerk, prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 06/30/18) 2 of 196 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 06/30/18) 3 of 196 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH 43215-9015 Minutes - Final columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council ELECTRONIC READING OF MEETING DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE DURING COUNCIL OFFICE HOURS. CLOSED CAPTIONING IS AVAILABLE IN COUNCIL CHAMBERS. -

Smart Logistics Electrification Rural Mobility Flyohio City Solutions

Rural Mobility FlyOhio Electrification Smart Logistics City Solutions Table of Contents Letter from the Director .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Focus on Safety ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Smart Mobility in Ohio ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Unmanned Aerial Systems .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Electrification ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.3. Smart Logistics ............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.4. City Solutions................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.5. Rural Mobility Solutions ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Performance Measurement Plan (Pfmp) for the Smart Columbus Demonstration Program

Performance Measurement Plan (PfMP) for the Smart Columbus Demonstration Program FINAL REPORT | June 2019 Produced by City of Columbus Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because it is essential to the contents of the work. Acknowledgment of Support This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation under Agreement No. DTFH6116H00013. Disclaimer Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the Author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Acknowledgments The Smart Columbus Program would like to thank project leads and local stakeholders for each of the Smart Columbus projects for their assistance in drafting and reviewing this Smart Columbus Performance Measurement Plan. Performance Measurement Plan (PfMP) – Final Report | Smart Columbus Program | i Abstract This Performance Measurement Plan describes the outcomes of Smart Columbus and how the objectives of each of projects relate to them. The plan identifies and explains the methodology proposed to evaluate the indicators for each project, which will provide insight into the performance of a project in meeting the objectives. The plan also describes the data necessary to evaluate the objectives and the required reporting frequency and contents. The responsibilities and types of interactions between the City of Columbus and an independent evaluator are also described. -

COC Celebrateone 2019-20 Annual Report V14.Indd

2019-2020 COMMUNITY IMPACT ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CELEBRATEONE GOVERNING BOARD Dr. Mysheika Roberts, Chair Health Commissioner, Columbus Public Health Karen Morrison, Vice-Chair President, OhioHealth Foundation and Senior Vice President, OhioHealth Stephanie Hightower, Treasurer President and CEO, Columbus Urban League Erik Janas, Secretary Deputy County Administrator, Franklin County Board of Commissioners Cathy Lyttle, Immediate Past Chair Senior Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer, Worthington Industries Teddy Ceasar Pastor, Destiny Church International Dan Crane Vice President, Crane Group Tracy Davidson CEO, United Healthcare Honorable Andrew J. Ginther Mayor, City of Columbus Rebecca Howard Parent What’s Inside... Timothy C. Robinson CEO, Nationwide Children's Hospital Maureen Stapleton Executive Director, CelebrateOne, Letter from Mayor Ginther & Board Chair Dr. Roberts ............................................................................4 ex-officio and non-voting Letter from the Executive Director ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Then and Now: Community Impact ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 One of the most profound and One Mom’s Story ...........................................................................................................................................7 heartbreaking impacts of systemic racism and poverty is the loss of our Then: Our Evolution -

20-24 Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan

Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report | Report Number 20-24 | August 2020 NYSERDA Department of Transportation Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report Prepared for: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority New York, NY Robyn Marquis Project Manager and New York State Department of Transportation Albany, NY Mark Grainer Joseph Buffamonte, Region 5 Project Managers Prepared by: Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. & WSP USA Inc. Buffalo, New York NYSERDA Report 20-24 NYSERDA Contract 112009 August 2020 NYSDOT Project No. C-17-55 Notice This report was prepared by Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. in coordination with WSP USA Inc., in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (hereafter “NYSERDA”). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of NYSERDA or the State of New York, and reference to any specific product, service, process, or method does not constitute an implied or expressed recommendation or endorsement of it. Further, NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no warranties or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any product, apparatus, or service, or the usefulness, completeness, or accuracy of any processes, methods, or other information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no representation that the use of any product, apparatus, process, method, or other information will not infringe privately owned rights and will assume no liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from, or occurring in connection with, the use of information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. -

Community Profile

Community Profile 1800s 1920s 2012 The National Road Ohio Stadium, Columbus celebrates is completed, the First Union Battelle Institute, its bicentennial. Station opens. Columbus and the airport (CMH), The city grew from is linked to other now known as the John 1,200 residents to markets resulting in a Glenn Columbus 750,000 in 200 years. boom in industry. International Airport, opened. 1812 1913 1950s - 1960s Columbus was founded The Great Flood Significant highway at the confluence of caused the death of projects were underway the Scioto and hundreds of Ohioans in Columbus, Olentangy rivers and resulted in including Interstates millions of dollars in 70 and 71 property damage. and State Route 315. TODAY Columbus is now the 14th largest city in the nation and the 2nd largest in the midwest. Source: Columbus History Columbus was founded in 1812 at the confluence of the 226 square miles, the city is recognized nationwide for Scioto and Olentangy rivers. In 1803, the year of Ohio’s its historic neighborhoods, booming downtown arts and statehood, the capital was moved from Chillicothe, sporting district,open attitude, and notably affordable located 45 miles to the south, to Zanesville, located quality of life. The city’s economy is very diverse and the 50 miles to the east, and back to Chillicothe. Created community prides itself on being at the forefront of educa- specifically to be the capital city, state officials finally tion reform, fiscal responsibility, and public safety. selected a centralized location in Columbus in 1812 and the city officially became Ohio’s permanent capital in 1816. -

As Passed by the Senate 132Nd General Assembly Regular Session

As Passed by the Senate 132nd General Assembly Regular Session H. B. No. 529 2017-2018 Representative Ryan Cosponsors: Representatives Smith, R., Cera, Ramos, Rogers, Anielski, Antonio, Arndt, Barnes, Brown, Celebrezze, Clyde, Edwards, Fedor, Galonski, Gavarone, Ginter, Green, Greenspan, Hambley, Hill, Holmes, Hoops, Householder, Howse, Hughes, Johnson, Landis, Lang, LaTourette, Leland, Lepore-Hagan, Manning, McClain, Miller, O'Brien, Patterson, Patton, Pelanda, Perales, Reineke, Riedel, Schaffer, Schuring, Seitz, Sheehy, Slaby, Smith, K., Strahorn, Sweeney, West, Young Speaker Rosenberger Senators Lehner, Beagle, Oelslager, Brown, Burke, Dolan, Eklund, Gardner, Hackett, Hoagland, Hottinger, Kunze, LaRose, Manning, Obhof, O'Brien, Peterson, Schiavoni, Skindell, Sykes, Tavares, Terhar, Thomas, Uecker, Williams, Wilson, Yuko ABILL To amend section 164.05 of the Revised Code to make 1 capital appropriations and changes to the law 2 governing capital projects and to make 3 reappropriations for the biennium ending June 30, 4 2020. 5 BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF OHIO: Section 101.01. That section 164.05 of the Revised Code be 6 amended to read as follows: 7 Sec. 164.05. (A) The director of the Ohio public works 8 H. B. No. 529 Page 2 As Passed by the Senate commission shall do all of the following: 9 (1) Approve requests for financial assistance from district 10 public works integrating committees and enter into agreements with 11 one or more local subdivisions to provide loans, grants, and local 12 debt support and -

Report to the Community

2020 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY To support and advance the arts and cultural fabric of Columbus. 2 Give Now VISION A thriving Columbus where the arts matter to all of us. VALUES Cultural Equity Our transparent grant making elevates and supports a broad representation of art forms and artists. Cultural Capital We are diligent stewards of the public and private support that drives our work. Sustaining Excellence We encourage excellence in the fields of the artists and arts organizations that we support, and in their fiscal and governance responsibilities. Building Community Our investments connect the people and places of Columbus. Welcome All We promote art experiences for those living, working, visiting and learning in our city. Inspired Advocacy Communicating the impact of the arts is fundamental to the health and vitality of the creative community. All the Black Lives Matter murals featured in this report were created in June 2020 in response to the protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Cover: Black Lives Matter mural by Gabe Torres. Originally located in the Short North. Opposite: Black Lives Matter mural created by unknown artist. Originally located at Salon Lofts at the Hub in the Short North. Photo credit: Shellee Fisher. Give Now 3 Black Lives Matter mural by Kelsey Yappel and Erik Johnson. Originally located at Store 5a in the Short North. Photo credit: Shellee Fisher. The Greater Columbus Arts Mayor Andrew J. Ginther Council thanks the city of Columbus City Council Members Columbus, Franklin County Shannon G. Hardin, president and the Ohio Arts Council for Elizabeth C. -

Smart Columbus Powered by Integrated Data Exchange (IDE)

Smart Columbus Powered by Integrated Data Exchange (IDE) Department of Technology Translational Data Analytics Institute Shoreh Elhami, Director, GIS/IDE Program Manager Christopher Stewart, Faculty-In-Residence Smart Columbus Confluence of Civic, Research & Startup Cultures • Winner $40M DOT Smart City Challenge • $367M investment local businesses & partners • $93M for research (largely from The Ohio State University) • $10 M Vulcan Inc. “Smart Columbus is just the start. There is a lot to this program no one has ever done before.” Mayor Andrew Ginther, 2016 Slide 2 Confluence of 3 Disruptive Data Trends Anyone can access, understand, use and share Internet Open Data of Open Things IoT: Devices embedded in the physical world– Data e.g., bodies, busses, and businesses Smart Cities Smart cities actively collect data and adapt policies and services to make citizenry successful Smart Columbus Slide 3 Data Flows From and Through Cities Central Ohio Transit Authority Ridership (Millions of Rides Per Year) 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 • Public -Private Partnerships: COTA is funded by 0.5% sales tax through 2019 • Starting 2017, On-board Wi-Fi will produce 4.7 TB per month • How does the city ingest, analyze and use all of this data? Slide 4 Smart City Applications Abound • CoGo opens trip data – https://www.cogobikeshare.com/system-data – Discover new bike paths – Over -provisioned and under-provisioned paths – Activity levels of citizens Slide 5 Who rises to the challenge? Who makes Smart Columbus? Challenges: Align For-Profit and Not-For-Profit Incentives, Find people with the right skills, Politics Any problem in computer science can be solved with another level of indirection. -

Community Profile Columbus Was Founded in 1812 at the Confluence of the Scioto and Olentangy Rivers. in 1803, the Year of Ohio S

Community Profile Columbus was founded in 1812 at the confluence of the Covering almost 225 square miles, the city is recognized Scioto and Olentangy rivers. In 1803, the year of Ohio’s nationwide for its historic neighborhoods, booming statehood, the capital was moved from Chillicothe, downtown arts and sporting district, open attitude, and located 45 miles to the south, to Zanesville, located 50 notably affordable quality of life. The city’s economy is miles to the east, and back to Chillicothe. Created diverse, and the community prides itself on being at the specifically to be the capital city, state officials finally forefront of technology, fiscal responsibility, and selected a centralized location in Columbus in 1812 and innovation. Economic investments in the future of the city officially became Ohio’s permanent capital in 1816. Columbus have created jobs and spurred major initiatives Columbus is ranked the 14th most populated city focused on improving neighborhoods, community in the United States. health, and the environment. Community Profile Columbus Government Key City Services at a Glance Development Annual Average Emergency & Non-Emergency Requests………………….40,865 Annual Average Code Violation Notices………20,280 Neighborhoods Neighborhood Pride Centers.......................................5 311 Service Requests Received in 2017………354,301 Public Health Licensed Food Facilities Compliant with Health Standards…………………99% Annual Average Immunizations………………..30,208 Public Safety Annual Average EMS & Fire Runs Dispatched………………………... 179,025 The city is a home-rule municipal corporation operating Fire Stations…………………………………………..33 under the laws of Ohio. The City Charter, its constitution, can only be amended by a majority of the Police Substations..................................................16 city’s voters. -

Smart Columbus” Vision Won the U.S

WE ARE THE SMART CITY! OUR VISION ACCESS SMART CONNECTED CONNECTED SUSTAINABLE TO JOBS LOGISTICS RESIDENTS VISITORS TRANSPORTATION The City of Columbus “Smart Columbus” vision won the U.S. Department of Transportation $40 million Smart City Challenge in June, 2016 after competing against 77 cities nationwide to become the country’s first city to fully integrate innovative technologies – self-driving cars, connected vehicles, and smart sensors – into their transportation network. Columbus was also awarded an additional $10 million grant from Paul G. Allen’s Vulcan Inc. to accelerate the transition to an electrified, low-emissions transportation system. Smart Columbus will: • Improve access to jobs through expanded mobility options in major job centers • Compete globally through smart logistics • Connect Columbus residents to safe, reliable transportation that can be accessed by all • Better connect our visitors to transportation options • Develop a more environmentally sustainable transportation system. THE COLUMBUS WAY Columbus has built an unprecedented culture of collaboration. By knocking down silos and building partnerships, Columbus has quickly become one of the fastest growing cities in the country, leading the Midwest in job and wage growth. The City of Columbus is matching the USDOT and Vulcan grants with $90 million in pledges from public and private sector partners. OUTCOME: A SAFER, MORE MOBILE AND SUSTAINABLE CITY Columbus will become the nation’s epicenter for intelligent transportation systems (ITS) research to improve safety, enhance mobility, create ladders of opportunity for those who may have been left behind in the past, and address climate change by reducing emissions. SAFETY MOBILITY OPPORTUNITY CLIMATE CHANGE transportation.gov columbus.gov/smartcolumbus vulcan.com 11/11/16 v2 STATE-OF-THE-ART PROJECTS Smart Columbus will develop, deploy and share lessons learned for 15 USDOT-funded and 9 Vulcan-funded initiatives within the following framework and districts. -

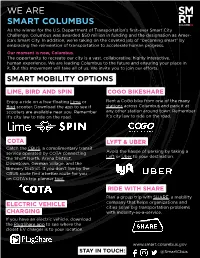

WE ARE SMART COLUMBUS As the Winner for the U.S

WE ARE SMART COLUMBUS As the winner for the U.S. Department of Transportation’s first-ever Smart City Challenge, Columbus was awarded $50 million in funding and the designation as Amer- ica’s Smart City. In addition, we’re taking on the coveted job of “becoming smart” by embracing the reinvention of transportation to accelerate human progress. Our moment is now, Columbus. The opportunity to recreate our city is a vast, collaborative, highly interactive, human experience. We are leading Columbus to the future and ensuring your place in it. But this movement will take all of us. We invite you to join our efforts. SMART MOBILITY OPTIONS LIME, BIRD AND SPIN COGO BIKESHARE Enjoy a ride on a free-floating Lime or Rent a CoGo bike from one of the many Bird scooter. Download the app to see if stations across Columbus and park it at scooters are available near you. Remember any other station around town. Remember it’s city law to ride on the road. it’s city law to ride on the road. COTA LYFT & UBER Catch the CBUS, a complimentary transit service operated by COTA connecting Avoid the hassle of parking by taking a the Short North, Arena District, Lyft or Uber to your destination. Downtown, German Village, and the Brewery District. If you don’t live by the CBUS route find a better route for you on COTA’s trip planner tool. RIDE WITH SHARE Plan a group trip with SHARE, a mobility company that helps organizations and ELECTRIC VEHICLE cities solve big transportation problems CHARGING with mobility-as-a-service.