Building a Consensus for the Development of National Standards in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stroke Seminar Credited with Saving Two Lives

Downey Distinguished Lady Bears crime report graduate have title hopes See Page 3 See Page 4 See Page 10 Thursday, Jan. 23, 2014 Vol. 12 No. 41 8301 E. Florence Ave., Suite 100, Downey, CA 90240 SHAT RED S ORIES: THE TIES THAT BIND STroKE semINAR CREDITED Dodi Soza Prisoner of War WITH SAVING TWO LIVES died Maria Zeeman was part of a large Dutch family living in Indonesia at the time of heart of the Japanese invasion in 1942. The following story reflects her memories as a • Hundreds receive no-cost six-year-old child when her life was turned upside down and she was a prisoner health screenings; more in a concentration camp. Her family was separated, but happily reunited in 1945 scheduled later this year. condition after the war. Shared Stories is a weekly column featuring articles by participants in a writing class at the Norwalk Senior Center. Bonnie Mansell is the instructor for this free class offered through the Cerritos College Adult Education Program. • Downey High football player Curated by Carol Kearns By Greg Waskul Contributor Dodi Soza died of heart failure, coroner rules. By Maria Zeeman I felt so big and was anxious about going into the first grade. We DOWNEY – Two lives were lived far from school and no one went to kindergarten at that time. saved and many other individuals By Christian Brown My brother John, who is thirteen months older than me, already did with life-threatening high blood Staff Writer go to school on the bus. He was so proud, telling BIG stories about it. -

Downey Thrust Into National News After Video of Brawl Goes Viral Downey

Thursday, Sept. 24, 2015 Vol. 14 No. 24 News News News Health Is Downey “Up With Retired police What causes selling out? Downey” officer honored laryngitis? SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 8 SEE PAGE 10 SEE PAGE 7 Downey High mourns death of student DOWNEY – Downey High School is in mourning this week following the unexpected death of 16-year-old student Joshua Ray Figueroa last Thursday. Downey thrust into national news Hundreds of family members, students, and faculty crowded around the campus bell tower last Saturday, lighting candles, embracing each other, and whispering prayers for after video of brawl goes viral Figueroa who tragically took his own life at his Bellflower home. By Alex Dominguez episode. Pro Tem Alex Saab said the fighting Friday Both faculty and students say Joshua was a kind depicted in the video isn’t indicative Weekend91˚ In a statement Monday, the and friendly teenager that was an active member of the Contributor Downey Police Department said of Downey’s values. Free Runners parkour team at Downey High School. at a officers were dispatched to the “As a local resident and parent, Glance DOWNEY – Video of a multiple “He called [them] his brothers,” said his mother person fight outside of Buffalo Wild restaurant at about 1:20 p.m. after I was appalled at the behavior I Anna Figueroa on a GoFundMe page set up on Saturday 6892˚⁰ Wings surfaced Sunday afternoon. receiving a call of two men fighting. witnessed in the video footage from Friday Tuesday to raise money for Joshua’s interment. “He “When the officers arrived, the this weekend, but I am confident was loved by many family and friends, and he is very The cellphone footage, posted on scene was calm, although one man that Downey Police will complete a missed by all.” Facebook by Dave Amaro, showed thorough investigation and justice multiple individuals trading blows claimed to have been involved in an Sunday 88˚ Currently, the family has collected nearly $1,800 towards a goal of will be served,” Marquez said. -

Chamber Presents $186000 in College Scholarships to 125 L.A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Marie Condron June 19, 2006 213.580.7532 Media must RSVP by 3 p.m. Monday, June 16 CHAMBER PRESENTS $186,000 IN COLLEGE SCHOLARSHIPS TO 125 L.A. AREA STUDENTS Chamber, elected officials partner with Education Financing Foundation of California to reward participants in Cash for College project at Paramount Studios reception WHAT: Cash for College Scholarship Reception WHEN: Tuesday, June 20, 6 - 8 p.m. WHERE: Paramount Studios, 5555 Melrose Ave., Hollywood All media must RSVP by 3 p.m. Monday for security clearance and parking. WHO: 125 L.A. area high school students and their families (names & schools follow) Los Angeles City Council President Eric Garcetti Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce Vice Chair David Fleming California Student Aid Commissioner David Roth Chamber V.P. of Education and Workforce Development David Rattray WHY: In partnership with the Education Financing Foundation of California, the L.A. Area Chamber will award $186,000 in college scholarships to 125 L.A. area high school students at the first-ever Cash for College Scholarship Awards Reception, sponsored by Paramount Studios and Wells Fargo. The scholarships are awarded to students who participated in the project’s College and Career Convention last fall and the more than 60 Cash for College workshops held throughout the L.A. area this spring. In the program’s four years, the workshops have helped over 65,000 L.A. students and families get free expert help on college and career opportunities and completing college financial aid forms. For more info on the project, visit http://www.lacashforcollege.org Most new jobs require a college education, and college graduates earn a million dollars more over a lifetime, on average, than those with only a high school diploma. -

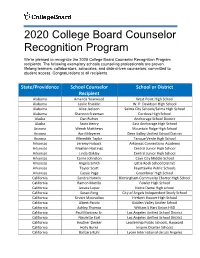

2020 Recognition Program

2020 College Board Counselor Recognition Program We’re pleased to recognize the 2020 College Board Counselor Recognition Program recipients. The following exemplary schools counseling professionals are proven lifelong learners, collaborators, advocates, and data-driven counselors, committed to student access. Congratulations to all recipients. State/Providence School Counselor School or District Recipient Alabama Amanda Yearwood West Point High School Alabama Leslie Franklin W. P. Davidson High School Alabama Alice Jackson Selma City Schools/Selma High School Alabama Shannon Freeman Cordova High School Alaska Dan Rufner Anchorage School District Alaska Scott Henry East Anchorage High School Arizona Wendi Matthews Mountain Ridge High School Arizona April Meyeres Deer Valley Unified School District Arizona Meredith Taylor Tanque Verde High School Arkansas Jeremy Hoback Arkansas Connections Academy Arkansas Meghan Hastings Central Junior High School Arkansas Linda Oakley Central Junior High School Arkansas Carrie Johnston Cave City Middle School Arkansas Angela Smith Little Rock School District Arkansas Taylor Scott Fayetteville Public Schools Arkansas Cassie Page Greenbrier High School California Sandra Harwin Birmingham Community Charter High School California Ramon Murillo Fowler High School California Jessica Lopez Notre Dame High school California Susan Fong City of Angels Independent Study School California Sirvart Mouradian Herbert Hoover High School California Albert Pando Golden Valley Unifier School California Ashley Thomas William -

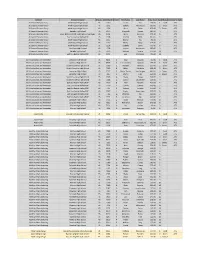

Session I - Grand Canyon University - Phoenix, Az

SESSION I - GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY - PHOENIX, AZ FIRST NAME LAST NAME PREFERRED FIRST NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION YEAR Jalen Adams Jalen Portland Oregon United States Jefferson High School 2021 Gaige Ainslie Gaige West Linn Oregon United States Central Catholic High School 2020 Carter Alberts Carter Cashmere Washington United States Cashmere High School 2021 DeDrick Allen DJ Signal Hill California United States St. Anthony High School 2021 Amound Anderson Amound Hawthorne California United States Leuzinger 2020 Garrett Andre Garrett Orange California United States Villa Park 2021 Brandon Angel Brandon San Diego California United States Torrey Pines 2020 Gregory Aranha III Greg Oakland California United States Bishop O'Dowd High School 2021 Yussif Basa-Ama Yussif Coconut Creek Florida United States Saint Andrew’s School 2021 Joshua Baugher Josh Albany Oregon United States Santiam Christian 2021 Mason Bayman Mason Newbury Park California United States Oaks Christian School 2020 Robby Beasley Robby San Ramon California United States Dougherty Valley High School 2020 Colby Bell Coco Santa Monica California United States Santa Monica High School 2020 Javon Bennett Javon Orlando Florida United States Trinity Preparatory School 2022 Love Bettis Love Cantonment Florida United States J.M. Tate High School 2020 Christian Bood Christian Torrance California United States Bishop Montgomery High School 2020 Kyle Braun Kyle Woodland Hills California United States Calabasas High School 2020 Declan Bretz Declan San Diego California -

Superintendents 3 Io It D K – 12 Public Schools E Los Angeles County Office of Education 9300 Imperial Hwy., Downey, CA 90242 562/922-6360

® FREE Education + Communication = A Better Nation www.schoolnewsrollcall.com Superintendents K – 1 2 Public Schools 3rd Edition Los Angeles County Office of Education 9300 Imperial Hwy., Downey, CA 90242 562/922-6360 www.lacoe.edu I am pleased to welcome you to School News Roll Call’s Los Angeles County Superintendents Issue for 2010-2011. As with past year’s well received editions, you will find here essential information not only about your own community school district, but the many neighboring districts, sampling the rich diversity that is Los Angeles County public education. There are 80 K-12 school districts spread across the 4,000 square miles of our county. The Los Angeles County Office of Education, which I direct, exists to serve all those districts and Darline P. Robles, their 1.6 million-plus students. We do this in many ways. Ph.D Superintendent As mandated by the state Legislature, “LACOE” certifies the financial health of individual districts and works with them to correct any budgetary problems. We also help districts save, and safeguard, their money through the cost-effective delivery of essential administrative and business services. We serve districts also by educating the county’s most vulnerable students, annually providing direct classroom instruction for about 27,000 young people, including children with severe disabilities, juvenile offenders and others at high risk of dropping out or with unique needs. Through our Early Advantage initiative, LACOE reaches out to students, families and communities with early childhood programs, parenting and literacy classes, as well as job development services. The centerpiece of our school- readiness efforts is the nation’s largest Head Start-State Preschool program, serving 22,000 preschool children and their families. -

Afterschool Programs

LOVE IS THE FOUNDATION OF EDUCATION. WE PUT LOVE INTO ACTION EVERY DAY. EduCare Foundation 2018-19 Annual Report Table of Contents 1 Vision and Values 2 President’s Letter 4 Our History 5 Our Approach 6 Who We Serve 8 EduCare Programs: Overview 10 ACE Program & ACE Initiative 12 Afterschool Programs 14 Core Afterschool Program Sites 15 Specialized Student Support Services 17 Professional Development 19 Parent & Family Skills Development Workshops 20 National & Local Recognition 21 Financials inside 22 The EduCare Team back cover 23 Supporters inside back Staying in Touch cover heartsetVision & values Our vision EduCare is effectively providing exemplary transformational education and afterschool programs for youth and those who support them. EduCare is preparing youth to be healthy, whole, successful and contributing citizens, and is empowering adults to be inspiring and supportive role models. EduCare is recognized as a leading and innovative youth service provider. EduCare is financially healthy with abundant resources to responsibly manage and • Children are our future expand its programs and seamlessly run the operations, including taking great care • Every child is valuable of our people. • Care for yourself and others • Trust and be trustworthy Our To inspiremission: and empower young people to • Everyone makes a difference become responsible citizens, compassionate leaders, • We teach what we live and to live their dreams. Our values page 1 | EduCare Foundation Annual Report President’s letterheartset For too many students from underserved communities, learning often takes a back seat to issues in their lives: poverty, trauma, and stress. These challenges can seem insurmountable without proper support and Outcomes show that EduCare’s holistic, guidance. -

Show Schedule

Saturday, April 4, 2020 2020 Monrovia High School Show @ Monrovia High School in Monrovia, California Winter Guard Association of Southern California (WGASC) Performance Schedule (as of 02/18/20) CLASS SCHOOL PERFORM JH AA Bellflower Middle School (JV) TBD* JH AA James Jordan Middle School TBD* JH AA Travis Ranch Middle School TBD* JH A Bellflower Middle School (Varsity) TBD* HS AA Van Nuys High School TBD* HS AA California High School Gold TBD* HS AA Eisenhower High School TBD* HS AA Chatsworth Charter High School TBD* HS AA Legacy High School TBD* HS AA Azusa High School TBD* HS AA Buena Park High School TBD* HS AA Lynwood High School TBD* HS AA James Monroe High School TBD* HS AA Herbert Hoover High School TBD* HS AA Saint Genevieve High School TBD* HS AA Costa Mesa High School TBD* HS AA Troy High School TBD* HS A Santee High School TBD* HS A Taft Charter High School TBD* HS A Burbank High School TBD* HS A California High School Blue TBD* HS A La Costa Canyon High School TBD* HS A Pasadena High School TBD* HS A Mark Keppel High School TBD* HS A Warren High School Junior (Varsity) TBD* HS A Damien High School TBD* HS A Camarillo High School TBD* HS A Oak Park High School TBD* HS A Ocean View High School TBD* HS A Montebello High School TBD* HS A Rosemead High School TBD* HS A La Habra High School TBD* HS A Golden Valley High School TBD* HS A Mayfair High School #2 TBD* HS A El Rancho High School TBD* Last Updated on 2/20/2020 at 9:55 PM Saturday, April 4, 2020 2020 Monrovia High School Show @ Monrovia High School in Monrovia, California -

Los Angeles County Districts

ABC School District 16700 Norwalk Boulevard Cerritos, CA 90703 562. 926-5566 Web Site www.abcusd.k12.ca.us 19 Elementary Schools 5 Middle Schools 3 four-year high schools 1 middle-senior high school 1 continuation-opportunity school 1 adult school K-12 enrollment 21, 265 Adult 16,000 ABC has a vision that is simple and powerful: We believe students in ABC should be as well educated as any in the world. We believe all students have the capacity to be high achievers. We believe people are the cornerstone of our district and students are the reason we are here." Community In 1965 Artesia, Bloomfield, and Carmenita School Districts unified and became known as the ABC Unified School District. The ABC Unified School District is representative of urban school districts throughout the United States. The community served by ABC Unified School District includes the cities of Artesia, Cerritos, Hawaiian Gardens, as well as portions of Lakewood, Long Beach, and Norwalk. Located in an attractive suburb on the southeast edge of Los Angeles County, the District is within easy driving distance to the major Southern California attractions, airports, and universities. The District is approximately 15 miles from beautiful Pacific Ocean beaches popular for their boating, surfing and sunning activities, and within two hours of mountain resorts for skiing and hiking. The ethnically and economically diverse community is strongly supportive of their ABC schools. The ABC Unified School District is known throughout the State of California as a leader in educational planning and innovation. The District has received county, state, and national recognition for outstanding programs in counseling, alternative education, staff development and labor relations. -

Inside Here’S to a Happy Retirement… This Issue Calendar of Events

The Weekly Newspaper of El Segundo Herald Publications - El Segundo, Hawthorne, Lawndale & Inglewood Community Newspapers Since 1911 - (310) 322-1830 - Vol. 108, No. 1 - January 3, 2019 Inside Here’s to a Happy Retirement… This Issue Calendar of Events ............2 Certified & Licensed Professionals ....................11 Classifieds ...........................4 Crossword/Sudoku ............4 Entertainment .....................6 Legals ........................... 10,11 Letters ..................................3 Pets .....................................12 During the holidays, the El Segundo Fire Department family took Firefighter/Paramedic Dina Carr out to lunch to celebrate her last day on the job after 25 years, to congratulate her on her retirement Real Estate. .....................7-9 and thank her for her service. Her colleagues said they will miss her around the station. Photo: ESFD. Sports ................................5,6 El Segundo Year in Review, Part 2 By Brian Simon Golf to improve and manage the nine-hole elected remaining incumbent Emilee Layne Last week’s first part of the 2018 year-end golf course. as well as newcomers Paulette Caudill and review focused mainly on matters within In other golf-related news, the Council in Tracey Miller-Zarneke. El Segundo voters the City of El Segundo itself, including March approved fee increases for the greens also passed (just over 60 percent in favor) department and financial highlights. This and driving range – the first since 2013 – so the $92 million Measure E bond to improve Weekend edition takes a look at other major news those are commensurate with other facilities school facilities, equipment, programs and items that made the headlines as well as the in the surrounding area. enhance site safety. Additionally, the El Forecast top school-related stories. -

Contest School / Chapter Division

Contest School / Chapter Division Contestant # Team First Name Last Name Total ScoreRank Medal Advance to State 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1260 Carina Tan 936.00 1 Gold ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1261 Isabela Villanueva 935.00 2 Silver ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1256 Neza Chow 890.00 3 Bronze ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Reseda High School HS 2160 Maiyanah Haynes 885.00 4 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Sylmar Biotech Health and Engineering Magne HS 2194 Gesel Sanchez 875.00 5 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story East San Gabriel Valley ROP HS 1998 LOGAN TANG 810.00 6 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1255 Danika Wu 795.00 7 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1259 Haley Hong 795.00 7 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Mark Keppel High School HS 1258 Isabelle Boun 775.00 8 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Van Nuys High School HS 1708 Joshua Hernandez 650.00 9 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story Reseda High School HS 2496 Michael Guerra 475.00 10 ATS 20 Second Elevator Story East San Gabriel Valley ROP HS 2123 Esai Rodriguez 150.00 11 3-D Visualization and Animation Lynwood High School HS 8464 K Jose Quijada 745.00 1 Gold ATS 3-D Visualization and Animation Lynwood High School HS 8464 K Jose Osvaldo Quijada 745.00 1 Gold ATS 3-D Visualization and Animation South Pasadena High School HS 7029 B Maxwell Hinman 665.00 2 Silver ATS 3-D Visualization and Animation South Pasadena High School HS 7029 B Ethan Martinez 665.00 2 Silver ATS 3-D Visualization -

2021 Chapter Excellence Program Chapters Recognition

2021 Chapter Excellence Program Chapters ALABAMA Gold Chapters of Distinction Escambia-Brewton Career Technology Center Silver Chapters of Distinction Pickens County Career Center Bronze Chapters of Distinction Bevill State Community College - Fayette Quality Chapters Anniston High School, Carpentry Auburn High School Blount County Center for Technology Bryant Career Technology Center, Carpentry Butler County Career Academy Dallas County Career Technology Center Elba High School Etowah Career Technology Center Hewitt-Trussville High School McAdory High School, Industrial Electricity Montgomery Preparatory Academies, Carpentry Reid State Technical College Tuscaloosa Career and Technology Academy, Cosmetology Tuscaloosa Career and Technology Academy ARKANSAS Gold Chapters of Distinction Huntsville High School Quality Chapters Oden High School ARIZONA Model of Excellence Chapters Valley Academy for Career and Technology Education Gold Chapters of Distinction River Valley High School San Luis High School Verrado High School Silver Chapters of Distinction La Joya Community High School Willow Canyon High School Yuma High School Bronze Chapters of Distinction Higley High School, Graphic Communications Pima County JTED @ Master Pieces Quality Chapters Pima County JTED @ Camino Seco Pima County JTED at STAR Rio Rico High School Valley Vista High School West-MEC SW Campus CALIFORNIA Gold Chapters of Distinction Victor Valley High School Silver Chapters of Distinction Downey High School Folsom High School Pioneer High School South Pasadena High