The White, Night Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense By Bob Carroll Paul Brown “always wanted his players to better themselves, and he wanted us known for being more than just football players,” Tony Adamle told an Akron Beacon Journal reporter in 1999. In the case of Adamle, the former Cleveland Browns linebacker who passed away on October 8, 2000, at age 76, his post-football career brought him even more honor than captaining a world championship team. Tony was born May 15, 1924, in Fairmont, West Virginia, to parents who had immigrated from Slovenia. By the time he reached high school, his family had moved to Cleveland where he attended Collinwood High. From there, he moved on to Ohio State University where he first played under Brown who became the OSU coach in 1941. World War II interrupted Adamle’s college days along with those of so many others. He joined the U.S. Air Force and served in the Middle East theatre. By the time he returned, Paul Bixler had succeeded Paul Brown, who had moved on to create Cleveland’s team in the new All-America Football Conference. Adamle lettered for the Buckeyes in 1946 and played well enough that he was selected to the 1947 College All-Star Game. He started at fullback on a team that pulled off a rare 16-0 victory over the NFL’s 1946 champions, the Chicago Bears. Six other members of the starting lineup were destined to make a mark in the AAFC, including the game’s stars, quarterback George Ratterman and running back Buddy Young. -

Statistical Leaders of the ‘20S

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 2 (1992) Statistical Leaders of the ‘20s By Bob GIll Probably the most ambitious undertaking in football research was David Neft’s effort to re-create statistics from contemporary newspaper accounts for 1920-31, the years before the NFL started to keep its own records. Though in a sense the attempt had to fail, since complete and official stats are impossible, the results of his tireless work provide the best picture yet of the NFL’s formative years. Since the stats Neft obtained are far from complete, except for scoring records, he refrained from printing yearly leaders for 1920-31. But it seems a shame not to have such a list, incomplete though it may be. Of course, it’s tough to pinpoint a single leader each year; so what follows is my tabulation of the top five, or thereabouts, in passing, rushing and receiving for each season, based on the best information available – the stats printed in Pro Football: The Early Years and Neft’s new hardback edition, The Football Encyclopedia. These stats can be misleading, because one man’s yardage total will be based on, say, five complete games and four incomplete, while another’s might cover just 10 incomplete games (i.e., games for which no play-by-play accounts were found). And then some teams, like Rock Island, Green Bay, Pottsville and Staten Island, often have complete stats, based on play-by-plays for every game of a season. I’ll try to mention variations like that in discussing each year’s leaders – for one thing, “complete” totals will be printed in boldface. -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 5 (1985) THE 1920s ALL-PROS IN RETROSPECT By Bob Carroll Arguments over who was the best tackle – quarterback – placekicker – water boy – will never cease. Nor should they. They're half the fun. But those that try to rank a player in the 1980s against one from the 1940s border on the absurd. Different conditions produce different results. The game is different in 1985 from that played even in 1970. Nevertheless, you'd think we could reach some kind of agreement as to the best players of a given decade. Well, you'd also think we could conquer the common cold. Conditions change quite a bit even in a ten-year span. Pro football grew up a lot in the 1920s. All things considered, it's probably safe to say the quality of play was better in 1929 than in 1920, but don't bet the mortgage. The most-widely published attempt to identify the best players of the 1920s was that chosen by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee in celebration of the NFL's first 50 years. They selected the following 18-man roster: E: Guy Chamberlin C: George Trafton Lavie Dilweg B: Jim Conzelman George Halas Paddy Driscoll T: Ed Healey Red Grange Wilbur Henry Joe Guyon Cal Hubbard Curly Lambeau Steve Owen Ernie Nevers G: Hunk Anderson Jim Thorpe Walt Kiesling Mike Michalske Three things about this roster are striking. First, the selectors leaned heavily on men already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There's logic to that, of course, but the scary part is that it looks like they didn't do much original research. -

Mcafee Takes a Handoff from Sid Luckman (1947)

by Jim Ridgeway George McAfee takes a handoff from Sid Luckman (1947). Ironton, a small city in Southern Ohio, is known throughout the state for its high school football program. Coach Bob Lutz, head coach at Ironton High School since 1972, has won more football games than any coach in Ohio high school history. Ironton High School has been a regular in the state football playoffs since the tournament’s inception in 1972, with the school winning state titles in 1979 and 1989. Long before the hiring of Bob Lutz and the outstanding title teams of 1979 and 1989, Ironton High School fielded what might have been the greatest gridiron squad in school history. This nearly-forgotten Tiger squad was coached by a man who would become an assistant coach with the Cleveland Browns, general manager of the Buffalo Bills and the second director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The squad featured three brothers, two of which would become NFL players, in its starting eleven. One of the brothers would earn All-Ohio, All-American and All-Pro honors before his enshrinement in Canton, Ohio. This story is a tribute to the greatest player in Ironton High School football history, his family, his high school coach and the 1935 Ironton High School gridiron squad. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the undefeated and untied Ironton High School football team featuring three players with the last name of McAfee. It was Ironton High School’s first perfect football season, and the school would not see another such gridiron season until 1978. -

Situation Analysis Scenario

SITUATION ANALYSIS SCENARIO Sports Marketing q Pretend you work for a sports team and that you are considering acquiring a player from another team. Prepare a document that tells me: q History of the team, history of the position, current trends or issues facing team, the need for this type of player, the need for this specific player, present the stats with an argument for 3 viable players, present other issues that will effect the team’s roster, and present which player you would recommend. Team Chosen: Chicago Bears Position Being Sought: Quarterback HISTORY OF TEAM Chicago Bears q 1920s: George Halas founded a pro football league & the Decatur Staley’s in 1920 1 q Franchise was renamed the Chicago Bears in January of 1922 q Games were played at Wrigley Field in front of 36,000 people q 1930s: The Bears won the 1932 Championship before 11,198 fans at Chicago Stadium under Coach Ralph Jones 2 q The National Football League was created in 1933 q The franchise lost $18,000 that season; Halas returned to coach q 1940s: Luke Johnsos and Hunk Anderson co-coached the Bears during WWII when Halas was sent overseas; Bears won title in 1946 3 HISTORY OF TEAM q 1950s: In 1958, the Bears and Los Angeles Rams establish an NFL attendance record drawing 100,470 in the LA Coliseum 4 q 1960s: A new era was signaled in 1965 when the club drafted Dick Butkus and Gale Sayers in the 1st round of the college draft 5 q In 1968, Halas retired from coaching after 40 seasons and a 324-151-31 record q 1970s: The Bears played their final season in Wrigley Field in 1970 before moving to Soldier Field 6 q In 1975, Walter Payton was the club's first-round draft choice q After a 14-year hiatus, the Bears returned to the playoffs in 1977 and in 1979 under head coach Neill Armstrong q The organization suffered a major loss at end of the decade when team president George 'Mugs' Halas, Jr. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist 1 Norm Van Brocklin 2 Otto Graham 3 Doak Walker 4 Steve Owen 5 Frankie Albert 6 Laurie Niemi 7 Chuck Hunsinger 8 Ed Modzelewski 9 Joe Spencer 10 Chuck Bednarik 11 Barney Poole 12 Charley Trippi 13 Tom Fears 14 Paul Brown 15 Leon Hart 16 Frank Gifford 17 Y.A. Tittle 18 Charlie Justice 19 George Connor 20 Lynn Chandnois 21 Bill Howton 22 Kenneth Snyder 23 Gino Marchetti 24 John Karras 25 Tank Younger 26 Tommy Thompson 27 Bob Miller 28 Kyle Rote 29 Hugh McElhenny 30 Sammy Baugh 31 Jim Dooley 32 Ray Mathews 33 Fred Cone 34 Al Pollard 35 Brad Ecklund 36 John Lee Hancock 37 Elroy Hirsch 38 Keever Jankovich 39 Emlen Tunnell 40 Steve Dowden 41 Claude Hipps 42 Norm Standlee 43 Dick Todd Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Babe Parilli 45 Steve Van Buren 46 Art Donovan 47 Bill Fischer 48 George Halas 49 Jerrell Price 50 John Sandusky 51 Ray Beck 52 Jim Martin 53 Joe Bach 54 Glen Christian 55 Andy Davis 56 Tobin Rote 57 Wayne Millner 58 Zollie Toth 59 Jack Jennings 60 Bill McColl 61 Les Richter 62 Walt Michaels 63 Charley Conerly 64 Howard Hartley 65 Jerome Smith 66 James Clark 67 Dick Logan 68 Wayne Robinson 69 James Hammond 70 Gene Schroeder 71 Tex Coulter 72 John Schweder 73 Vitamin Smith 74 Joe Campanella 75 Joe Kuharich 76 Herman Clark 77 Dan Edwards 78 Bobby Layne 79 Bob Hoernschemeyer 80 Jack Carr Blount 81 John Kastan 82 Harry Minarik 83 Joe Perry 84 Ray Parker 85 Andy Robustelli 86 Dub Jones 87 Mal Cook 88 Billy Stone 89 George Taliaferro 90 Thomas Johnson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

Hall of Fame Admission Promotion Offered to Steelers and Browns Fans

Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE @ProFootballHOF 11/17/2016 Contact: Pete Fierle, Chief of Staff & Vice President of Communications [email protected]; 330-588-3622 HALL OF FAME ADMISSION PROMOTION OFFERED TO STEELERS AND BROWNS FANS FANS VISITING REGION FOR THE WEEK 11 MATCH-UP TO RECEIVE SPECIAL ADMISSION DISCOUNT FOR WEARING TEAM GEAR CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame is inviting Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns fans in northeast Ohio this weekend to experience “The Most Inspiring Place on Earth!” The Steelers take on the Browns this Sunday (Nov. 20) at 1:00 p.m. at FirstEnergy Stadium. The Pro Football Hall of Fame is just under an hour’s drive south of Cleveland. Any Steelers or Browns fan dressed in their team’s gear who mentions the promotion at the Hall’s box office will receive a $5 discount on any regular price museum admission. The promotion runs from Friday, Nov. 18 through Monday, Nov. 21. The Hall of Fame is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Information about planning a visit to the Hall of Fame can be found at: www.ProFootballHOF.com/visit/. STEELERS IN CANTON The Steelers have 21 longtime members enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame – the third most by any current NFL franchise after the Chicago Bears (27) and the Green Bay Packers (24). Longtime Pittsburgh players include: JEROME BETTIS (Running Back, 1996-2005, Class of 2015), MEL BLOUNT (Cornerback, 1970-1983, Class of 1989), TERRY BRADSHAW -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Rote & Blanda: Tale of 2

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 16, No. 3 (1994) ROTE & BLANDA: TALE OF 2 QBS Birth of the AFL in 1960 changed the course of two careers By Bob Gill Any reasonably attentive sports fan is aware that chance can play a significant role in a player's career. An injury can give a backup his big break, while bringing a veteran's career to a premature end. A star's ill-timed holdout can be another player's ticket to fame and fortune. And so on - it happens every season. Usually, breaks like these benefit rookies or younger players who haven't had a chance at a regular job. But one of the most interesting "right-place-at-the-right-time" stories involves a pair of ten-year veterans whose places in football history were determined after their NFL careers ended. It happened in the 1960s, and the players involved were a couple of pretty fair quarterbacks: George Blanda and Tobin Rote. But let's start at the beginning ... Blanda broke in with the Bears in 1949, but the 12th-round draft choice saw little action behind Johnny Lujack and aging Sid Luckman. He played even less at QB for the next two years, throwing only one pass and spending most of his time as a linebacker and kicker. Meanwhile, Rote had been taken by the Packers in the second round of the 1950 draft and suffered through a tough rookie season, throwing a league-high 24 interceptions. Facing a challenge from a talented passer named Bobby Thomason in 1951, he improved his passing stats and really shone as a runner, leading the team with 523 yards and leading the league with an average of 6.9 yards per carry. -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

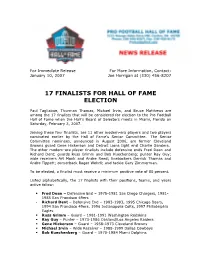

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999