Chilika Lagoon Chilika Lagoon: Restoring Ecological Balance and Livelihoods Through Re-Salinization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research and Investigations in Chilika Lake (1872 - 2017)

Bibliography of Publications Research and Investigations in Chilika Lake (1872 - 2017) Surya K. Mohanty Krupasindhu Bhatta Susanta Nanda 2018 Chilika Development Authority Chilika Development Authority Forest & Environment Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar Bibliography of Publications Research and Investigations in Chilika Lake (1872 - 2017) Copyright: © 2018 Chilika Development Authority, C-11, B.J.B. Nagar, Bhubaneswar - 751 014 Copies available from: Chilika Development Authority (A Government of Odisha Agency) C-11, B.J.B. Nagar Bhubaneswar - 751 014 Tel: +91 674 2434044 / 2436654 Fax: +91 674 2434485 Citation: Mohanty, Surya K., Krupasindhu Bhatta and Susanta Nanda (2018). Bibliography of Publications: Research and Investigations in Chilika Lake (1872–2017). Chilika Development Authority, Bhubaneswar : 190 p. Published by: Chief Executive, Chilika Development Authority, C-11, B.J.B. Nagar, Bhubaneswar - 751 014 Design & Print Third Eye Communications Bhubaneswar [email protected] Foreword Chilika Lake with unique ecological character featured by amazing biodiversity and rich fishery resources is the largest brackishwater lake in Asia and the second largest in the world. Chilika with its unique biodiversity wealth, ecological diversity and being known as an avian paradise is the pride of our wetland heritage and the first designated Indian Ramsar Site. The ecosystem services of Chilika are critical to the functioning of our life support system in general and livelihood of more than 0.2 million local fishers and other stakeholders in particular. It is also one of the few lakes in the world which sustain the population of threatened Irrawaddy Dolphin. Chilika also has a long history of its floral and faunal studies which begun since more than a century ago. -

Gel Diffusion Analysis of Anopheles Bloodmeals from 12 Malarious

DEcEMBER 1991 Gpr, Drprusror ANAr.vsrsor Bloortuonls GEL DIFFUSIONANALYSIS OF ANOPHELESBLOODMEALS FROM 12 MALARIOUS STUDY VILLAGES OF ORISSA STATE. INDIA R. T. COLLINS,I M. V. V. L. NARASIMHAM,' K. B. DHAL' AND B. P. MUKHEzuEE' ABSTRACT. In Orissa State, India, the double gel diffusion technique was used to analyze97,405 bloodmealsof all fed anophelinesthat were caught during standardizedmonthly surveysin 12 malarious study villages,from 1982through 1988.Anoph.eles culicifaci.es contributed the highest number of smears from the 19 Anophelcsspecies recovered. It was observedthat a pronouncedpredilection to take mixed bloodmealsattenuates the vector potential of the speciesconcerned. Consequently, prevalences based "pure" only upon (unmixed) primate bloodmealsprovide the most accurate way to assessthe intensity of feeding contact that actually occurs between a given speciesand man. By this method, the ranking order is Anophelesfluuintilis, An. culicifaci.esand An. annulnris (N); a sequencewhich concurs with current knowledgeon the vector status of malaria mosquitoesin Orissa. INTRODUCTION upgrade entomology, so 3 field studies were es- tablished in Orissa, with primary objectives to Anopheles sundaicus Rodenwaldt was de- incriminate or reincriminatevector speciesand scribed as a coastal vector of malaria by Senior to study larval and adult bionomics,particularly White (1937)and asa vectorin the Chilika Lake to improve control strategies.By the time a areaof Orissaby Covelland Singh (1942).Sub- double gel diffusion (DGD) mosquito bloodmeal sequently, early DDT malaria sprays appear to identification systemwas developed,the 3 study have eliminated An. sundaicusfrom coastal Or- teams already had been conducting weekly rou- issa,but it is still found in seashoreareas north tine field collections for more than a year, so it and south of the state. -

Conservation and Management of Bioresources of Chilika Lake, Odisha, India

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 7, July 2015 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Conservation and Management of Bioresources of Chilika Lake, Odisha, India N.Peetabas* & R.P.Panda** * Department of Botany, Science College, Kukudakhandi ** Department of Zoology, Anchalik Science College, Kshetriyabarapur Abstract- The Chilika lake is one of The Asia’s largest brackish with mangrove vegetation. The lagoon is divided into four water with rich biodiversity. It is the winter ground for the sectors like Northern, Central, Southern and Outer channel migratory Avifauna in the country. This lake is a highly It is the largest winter ground for migration birds on the productive ecosystem for several fishery resources more than 1.5 Indian sub-continent. The lake is home for several threatened lakh fisher folks of 132 villages and 8 towns on the bank of species of plants and animals. The lake is also ecosystem with Chilika directly depend upon the lagoon for their sustenance large fishery resources. It sustains more than 1.5 lakh fisher – based on a unique biodiversity and socio-economic importance. folks living in 132 villages on the shore and islands. The lagoon The lagoon also supports a unique assemblage of marine, brakish hosts over 230 species of birds on the pick migratory season. water and fresh water biodiversity. The lagoon also enrich with Birds from as far as the Casparian sea, lake Baikal, remote part avi flora and avi fauna , fishery fauna and special attraction for of Russia, Central and South Asia, Ladhak and Himalaya come eco-tourism. The other major components of the restoration are here. -

Tree Species Diversity in Chilika Lake Ecosystem of Odi India

International Research Journal of Environment Sciences _____________________________ ___ E-ISSN 2319–1414 Vol. 5(11), 1-7, November (2016) Int. Res. J. Environment Sci. Assessment of Tree Species Diversity in Chilika Lake Ecosystem of Odisha , India Jangyeswar Sahoo 1 and Manoj Kumar Behera 2* 1OUAT, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India 2NR Management Consultants India Pvt. Ltd., Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India [email protected] Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 1th June 2016, revised 11 th October 2016, accepted 12 th November 2016 Abstract A study was conducted to estimate the distribution and diversity of tree species in Chilika lake ecosystem, the largest lagoon in Asia. The present study was conducted in 2014 by laying out quadrats of desired size to estimate the diversity of tree species in three of the four ecological sectors namely northern, central and southern sector. A total of 69 tree species representing 57 genera and 33 families were recorded from the three ecological secto rs of Chilika. Among the three ecological sectors, northern sector was found superior in terms of species richness and diversity with 46 tree species per hectare of area. The total dominance of northern sector was also highest i.e. 36.35m 2/ha. Among the sp ecies documented, maximum value of Importance Value Index (IVI) was reported in Teak (21.69) followed by Casuarina (19.02) and Sal (14.95) respectively. The Shannon-Weiner Index value was found in the range of 1.5 to 3.5. It was observed that species diver sity in the ecological sectors is substantially influenced by intensity of human interference in and around them. -

PURI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD PURI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar March, 2013 1 PURI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl ITEMS Statistics No 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 3479 ii. Administrative Divisions as on 31.03.2011 Number of Tehsil / Block 7 Tehsils, 11 Blocks Number of Panchayat / Villages 230 Panchayats 1715 Villages iii Population (As on 2011 Census) 16,97,983 iv Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1449.1 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Very gently sloping plain and saline marshy tract along the coast, the undulating hard rock areas with lateritic capping and isolated hillocks in the west Major Drainages Daya, Devi, Kushabhadra, Bhargavi, and Prachi 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest Area 90.57 b) Net Sown Area 1310.93 c) Cultivable Area 1887.45 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alfisols, Aridsols, Entisols and Ultisols 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS Paddy 171172 Ha, (As on 31.03.2011) 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) Dugwells, Tube wells / Borewells DW 560Ha(Kharif), 508Ha(Rabi), Major/Medium Irrigation Projects 66460Ha (Kharif), 48265Ha(Rabi), Minor Irrigation Projects 127 Ha (Kharif), Minor Irrigation Projects(Lift) 9621Ha (Kharif), 9080Ha (Rabi), Other sources 9892Ha(Kharif), 13736Ha (Rabi), Net irrigated area 105106Ha (Total irrigated area.) Gross irrigated area 158249 Ha 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB ( As on 31-3-2011) No of Dugwells 57 No of Piezometers 12 10. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Alluvium, laterite in patches FORMATIONS 11. HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation 0.16 mbgl to 5.96 mbgl Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 2 Sl ITEMS Statistics No Post-monsoon Depth to water level during 0.08 mbgl to 5.13 mbgl 2011 Long term water level trend in 10 yrs (2001- Pre-monsoon: 0.001 to 0.303m/yr (Rise) 0.0 to 2011) in m/yr 0.554 m/yr (Fall). -

Dr. Lopamudra Mishra 2. Present Position: Assistant Professor (Stagei)

TEACHER’S DATASHEET 1. Name: Dr. Lopamudra Mishra 2. Present Position: Assistant Professor (StageI) 3. Mobile Number & Email: 9438160845. [email protected] 4. Date of Birth: 16th January, 1971 5. Date of joining in the Department with designation: 26th November,2015; Lecturer 6. Research papers published in journals during last five calendar years (2013-2017) Sl Title Authors Vol . No. ISSN Impact Factor (As No. (Issue)/Page/Year per Thomson Reuter) Economic and Lopamudra Vol 7, No 2, Management Environmental Mishra 2015 of Analysis of Sustainable Shrimp Farming Development, in Chilika Lake, ISSN:2247- India 0220 1. Books/Book Chapters published during last five calendar years (2013-2017): Sl Title of the Authors Publisher Page ISBN Impact Factor if No. book/Book No./ any (As per Chapter Year Thomson Reuter) Business Lopamudra Springer & Pp. 1-15, ISBN:978- Paradigms in Mishra 2014 93-5196- Emerging Tushar Kanti School of 520-6 Markets Das Management, NIT, Rourkela Business, Lopamudra NIT, Pp 111- ISBN: Innovation & Mishra Rourkela 130, 978-93- Sustainability: 2017 5268-051- Proceedings of 1 the National Management Conclave, 7. D.Sc./D.Litt/Ph.D Scholars guided (Awarded) during last five calendar years (2013-2017) l Name of the Guide/Co- Sambalpur D.Sc./ Notification No & No. Scholar Guide University/ Other D.Litt/Ph.D Date University 1 8. Patents if any during last five calendar years (2013-2017) Sl Title of the Authors Patent No. and Date National/International No. Patent 9. Sponsored Projects undertaken during last five Calendar years (2013-2017) Sl. Title of the PI and Co- Funding Date of Completed/ Amount No. -

Research Setting

S.K. Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Karma P. Kaleon Chapter–6 Research Setting Anshuman Jena, S K Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Lalu Das In any social science research, it is hardly possible to conceptualize and perceive the data and interpret the data more accurately until and unless a clear understanding of the characteristics in the area and attitude or behavior of people is at commend of the interpreter who intends to unveil an understanding of the implications and behavioral complexes of the individuals who live in the area under reference and from a representative part of the larger community. The socio demographic background of the local people in a rural setting has been critically administered in this chapter. A research setting is a surrounding in which inputs and elements of research are contextually imbibed, interactive and mutually contributive to the system performance. Research setting is immensely important in the sense because it is characterizing and influencing the interplays of different factors and components. Thus, a study on Perception of Farmer about the issues of Persuasive certainly demands a local unique with natural set up, demography, crop ecology, institutional set up and other socio cultural Social Ecology, Climate Change and, The Coastal Ecosystem ISBN: 978-93-85822-01-8 149 Anshuman Jena, S K Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Lalu Das milieus. It comprises of two types of research setting viz. Macro research setting and Micro research setting. Macro research setting encompasses the state as a whole, whereas micro research setting starts off from the boundaries of the chosen districts to the block or village periphery. -

Odisha Review

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXIII NO.5 DECEMBER - 2016 SURENDRA KUMAR, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary SUSHIL KUMAR DAS, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Kishor Kumar Sinha Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Rs.5/- Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Oh ! Blue Mountain ! Bhakta Salabeg Trans. by : Ramakanta Rout ... 1 Speech of Dr. S. C. Jamir, Hon'ble Governor of Odisha on the Birth Centenary Celebration of Legendary Leader Biju Patnaik ... ... 2 Good Governance ... ... 5 Keynote Address by Hon'ble Chief Minister at the Make in Odisha Conclave ... ... 10 Speech of Hon'ble Chief Minister at the Inaugural Session of the Odisha Round Table Organised by Business Standard ... ... 12 Hon'ble Chief Minister's Speech at the Indian Express Literary Festival ... ... 14 Light a Lamp and Remove the Darkness Biju Patnaik ... 15 Brain Storming Deliberations of Biju Patnaik ... ... 18 The Biju Phenomenon Prof. Surya Narayan Misra .. -

International Conference on Next Generation Libraries-2019 (NGL

राष्ट्रीय प्रौ饍योगिकी संस्थान,राउरकेऱा National Institute of Technology, Rourkela BIJU PATNAIK CENTRAL LIBRARY Empowering Library Professional to Empower Society (ELPES) – 7 International Conference on Next Generation Libraries-2019 (NGL-2019) New Trends & Technologies, Collaboration & Community Engagement, Future Librarianship, Library Spaces & Services December 12-14, 2019 TIIR Auditorium, NIT Rourkela, India Date: December 12-14, 2019 Venue: TIIR Auditorium Time: 9.00 AM to 5.30 PM Organized by Biju Patnaik Central Library National Institute of Technology, Rourkela in association with Special Libraries Association (SLA) USA, Asia Chapter (more details will be added soon) P:+91-661-2462101 | E: [email protected] | W: http://ngl2019.nitrkl.ac.in Call for Papers Empowering Library Professional to Empower Society (ELPES) – 7 International Conference on Next Generation Libraries-2019 (NGL-2019) New Trends & Technologies, Collaboration & Community Engagement, Future Librarianship, Library Spaces & Services December 12-14, 2019 TIIR Auditorium, NIT Rourkela, India As Information Professionals, we live in the age of digital information. Recent studies have shown that there is a drastic change in user demands needed to support the teaching, learning, and research activities of the library profession. The desire for physical library collections is in decline. Even though there is high demand for internet access and allied resources, there are certain user categories like traditional resources and demand for the physical space in the library. In such conditions, libraries may reconsider their current spaces and future renovations to reflect these usage trends to meet the changing requirements of the user community. In this international conference, library professionals from different regions of the world will discuss how Next Generation Libraries (NGL) can be useful for the library users. -

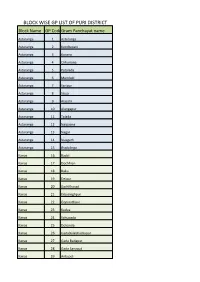

BLOCK WISE GP LIST of PURI DISTRICT Block Name GP Codegram Panchayat Name

BLOCK WISE GP LIST OF PURI DISTRICT Block Name GP CodeGram Panchayat name Astaranga 1 Astaranga Astaranga 2 Kendrapati Astaranga 3 Korana Astaranga 4 Chhuriana Astaranga 5 Patalada Astaranga 6 Manduki Astaranga 7 Saripur Astaranga 8 Sisua Astaranga 9 Alasahi Astaranga 10 Alangapur Astaranga 11 Talada Astaranga 12 Naiguana Astaranga 13 Nagar Astaranga 14 Nuagarh Astaranga 15 Jhadalinga Kanas 16 Badal Kanas 17 Dochhian Kanas 18 Baku Kanas 19 Deipur Kanas 20 GarhKharad Kanas 21 Dibysinghpur Kanas 22 Gopinathpur Kanas 23 Kadua Kanas 24 Sahupada Kanas 25 Dokanda Kanas 26 GadaBalabhadrapur Kanas 27 Gada Badaput Kanas 28 Gada Sanaput Kanas 29 Anlajodi Kanas 30 Pandiakera Kanas 31 Badas Kanas 32 Trilochanpur Kanas 33 Alibada Kanas 34 Bijipur Kanas 35 Andarsingh Kanas 36 Chupuring Kanas 37 Gadasahi Kanas 38 Jamalagoda Kanas 39 Gadisagoda Kanas 40 Kanas Kanas 41 Khandahata Kanas 42 Bindhan Kanas 43 Sirei Kakatpur 44 Kantapada Kakatpur 45 Katakana Kakatpur 46 Lataharan Kakatpur 47 Bhandaghara Kakatpur 48 Patasundarpur Kakatpur 49 Suhagapur Kakatpur 50 Jaleswarpada Kakatpur 51 Kakatapur Kakatpur 52 Kundhei Kakatpur 53 Othaka Kakatpur 54 Suhanapur Kakatpur 55 Kaduanuagaon Kakatpur 56 Abadana Kakatpur 57 Bangurigaon Kakatpur 58 Kurujanga Kakatpur 59 Nasikeswar Krushnaprasad 60 Alanda Krushnaprasad 61 Bada-anla Krushnaprasad 62 Badajhad Krushnaprasad 63 Bjrakote Krushnaprasad 64 Budhibar Krushnaprasad 65 Gomundia Krushnaprasad 66 Krushnaprasad Krushnaprasad 67 Malud Krushnaprasad 68 Ramalenka Krushnaprasad 69 Siala Krushnaprasad 70 Siandi Krushnaprasad -

Biodiversity of Chilika and Its Conservation, Odisha, India

International Research Journal of Environment Sciences_________________________________ ISSN 2319–1414 Vol. 1(5), 54-57, December (2012) Int. Res. J. Environment Sci. Biodiversity of Chilika and Its Conservation, Odisha, India Tripathy Madhusmita Department of Zoology, P.N. Autonomous College, Khordha, Odisha, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 01 st November 2012, revised 10 th November 2012, accepted 15 th November 2012 Abstract This paper identifies the uniqueness of the largest brackish water habitat in Asia, i.e. Chilika. The lagoon supports a unique assemblage of marine, brackish water and fresh water biodiversity. Four types of crocodiles, 24 types of mammals, 37 types of reptiles, 726 types of flowering plants, 5 types of grasses and mangroves are present here. People of 122 villages and 8 towns on the bank of Chilika depend upon its biodiversity for their livelihood. Marine produce and tourism activities around the lagoon contribute significantly to the economy of Odisha State. Keywords: Biodiversity, Chilika Lake, Lagoon, Avifauna Introduction large towns and 122 villages. 70% of the population in these habitations depend upon fishing as the only means of their Biological diversity refers to variety of life forms we see around livelihood. A revenue of about 70million rupees is collected us. It encompasses a diverse spectrum of mammals, birds, from 25 revenue villages on its bank annually. On an average reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects and other invertebrates, plants, 2.5lakh tourists visit this lake every year. fungi and micro-organisms such as protista, bacteria and virus. Biodiversity is recognized at three levels: i. Species diversity, e.g. cow, human or mango tree etc. -

Rs .31750 Destinations Overview Tour Highlights Itinerary

0484 4020030, 8129114245 [email protected] ORISSA TOUR PACKAGE Rs .31750 4 Nights 5 Days Destinations Orissa Overview Places covered : Puri, Lord Jagannath Temple, Chandra Bhaga Beach, Konark Sun Temple, Pipili, Chilika Lake Tour Highlights Konark Sun Temple Pipili Chandra Bhaga Beach Chilika Lake Puri Beach Lingaraj Temple Udaygiri & Khandagiri Itinerary Day 1 : Cochin – Bhuvaneswar Jagannath Temple ( Meal Plan: Dinner ) On arrival at Bhubaneswar Airport transfer to Hotel. Overnight stay in Hotel at Bhubaneswar. Day 2 : Puri – Konark Sightseeing ( Meal Plan: Breakfast - Lunch - Dinner ) After Breakfast visit Dawalgiri, Konark Sun Temple, Chandra Bhaga Beach. Evening free for shopping at Sea side where you can get some unique ornaments & showpieces made by Shell. Overnight stay at Puri. Day 3 : Excursion to Chilika Lake (50 Kms) ( Meal Plan: Breakfast - Lunch - Dinner ) After breakfast start for day excursion to Chilika Lake (Place called Satpada). It’s famous for Irrawaddy Dolphins. One can enjoy boating at Satpada (at own cost) and visit the lagoon where the lake meets with into Bay of Bengal. Next visit the Lord Jagannath Temple built in 15th Century AD and crowned with Vishnu’s wheel & flag dominate the landscape at Puri. Evening back to Puri. Overnight stay will be at Puri. Day 4 : Puri - Bhubaneswar Local Sightseeing ( Meal Plan: Breakfast-Lunch-Dinner ) After breakfast visit Pipili (the applique village), Nandankanan Zoological Park, Dhauli, Khandagiri, Udaygiri & Lingraj Temple. Evening drive back to Bhubaneswar. Overnight