Early Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

The Temple Classics

THE TEMPLE CLASSICS Edited by W. H. D. ROUSE M.A. First iss_t *f titis Edition, J898 ; R#printtd t908 , 191o PRINTZD IN OJUgAT BH|TAIN In compliance with eurre,lt copyright law, the Univer- sity of Minnesota Bindery produced this facsimile on permanent-durable paper to replace the irreparably deteriorated original volume owned by the University Library. 1988 TO THE MOST HIGH AND MIGHTV PRINCESS ELIZABETH By the Grace of God, of F.mghmd, France, It_ Ireland Queen, Defender of the Fltith, etc. U_DER hope of your Highness' gracious and accus- To the . tomed favour, I have presumed to present here wiaeamd _unto your Majesty, Plutarch's Lives translated, as virtuo,,- • a book fit to be protected by your Highness, and Queea -meet to be set forth in English--for who is , fitter to give countenance to so many great states, - than such an high and mighty Princess ._ who is fitter to revive the dead memory of their _', fame, than she that beareth the lively image of ...their vertues ? who is fitter to authorise a work _of so great learning and wisedom, than she whom all do honour as the Muse of the world ? Therefore I humbly beseech your Majesty, to -_suffer the simpleness of my translation, to be covered under the ampleness of your Highness' pro- _gtecfion. For, most gracious Sovereign, though _-this book be no book for your Majesty's self, =who are meeter to be the chief stone, than a '_student therein, and can better understand it in Greek, than any man can make in English: ' U;k_. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Silver epic catalogues Asquith, H.C.A. How to cite: Asquith, H.C.A. (2001) Silver epic catalogues, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4368/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk H. C. A. Asquith Silver Epic Catalogues A thesis presented for examination for the MA in Classics The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent AH information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. Supervisor: A, J. Woodman September 2001 f 9 APR 2002 H. Asquith September 2001 Silver Epic Catalogues Thesis for the MA in Classics Abstract This thesis aims to examine the detailed contents of epic catalogues from the Iliad through to the Silver epics, although it will concentrate upon the developments displayed in the latter period. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Silver epic catalogues Asquith, H.C.A. How to cite: Asquith, H.C.A. (2001) Silver epic catalogues, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4368/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk H. C. A. Asquith Silver Epic Catalogues A thesis presented for examination for the MA in Classics The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent AH information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. Supervisor: A, J. Woodman September 2001 f 9 APR 2002 H. Asquith September 2001 Silver Epic Catalogues Thesis for the MA in Classics Abstract This thesis aims to examine the detailed contents of epic catalogues from the Iliad through to the Silver epics, although it will concentrate upon the developments displayed in the latter period. -

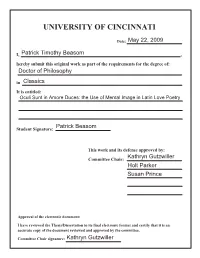

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 22, 2009 I, Patrick Timothy Beasom , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: the Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry Patrick Beasom Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller Holt Parker Susan Prince Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Kathryn Gutzwiller Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: The Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick Timothy Beasom B.A., University of Richmond, 2002 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2006 May 2009 Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller, Ph.D. Abstract Propertius tells us that the eyes are our guides in love. Both he and Ovid enjoin lovers to keep silent about their love affairs. I explore the ability of poetry to make our ears and our eyes guides, and, more importantly, to connect seeing and saying, videre and narrare. The ability of words to spur a reader or listener to form mental images was long recognized by Roman and Greek rhetoricians. This project takes stock for the first time of how poets, three Roman love poets, in this case, applied vivid description and other rhetorical devices to spur their readers to form mental images of the love they read. -

Philosophical Readings

PHILOSOPHICAL READINGS ONLINE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY Editor: Marco Sgarbi Volume XI – Issue 2 – 2019 ISSN 2036-4989 Special Issue: The Sophistic Renaissance: Authors, Texts, Interpretations Guest Editor: Teodoro Katinis ARTICLES Enhancing the Research on Sophistry in the Renaissance Teodoro Katinis .................................................................................................................. 58 Peri Theôn: The Renaissance Confronts the Gods Eric MacPhail..................................................................................................................... 63 Marsilio Ficino’s Commentary on Plato’s Gorgias Leo Catana........................................................................................................................... 68 Rhetoric’s Demiurgy: from Synesius of Cyrene to Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola Marco Munarini ................................................................................................................. 76 Observations on the Reception of the Ancient Greek Sophists and the Use of the Term Sophist in the Renaissance Marc van der Poel ............................................................................................................... 86 Atticism and Antagonism: How Remarkable Was It to Study the Sophists in Renaissance Venice? Stefano Gulizia.................................................................................................................... 94 From Wit to Shit: Notes for an “Emotional” Lexicon of Sophistry during the Renaissance -

The Ancient City

THE ANCIENT CITY: STUDY RELIGION, LAWS, AND INSTITUTIONS OF GREECE AND HOME. BT PUSTBL DB COULANGES. TRANSLATED FROM THE LATEST FRENCH EDITION BY WILLARD SMALL. TENTH EDITION. BOSTON: LEE AND SHEPARD. Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, By WILLARD SMALL, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Copyright, 1901, by Willard Small. CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. &" PAOB Necessity of studying the oldest Beliefs of the Ancients in order to understand their Institutions • BOOK FIRST. ANCIENT BELIEFS. CHAPTER I. Notions about the Soul and Death 15 II. The Worship of the Dead 23 III. The Sacred Fire IV. The Domestic Religion BOOK SECOND. THE FAMILY. OHAPTBB I. Religion was the constituent Principle of the an- cient Family II. Marriage aaiuag the Greeks and Romans. .... 68 III. The Continuity of the Family. Celibacy forbidden. Divorce in Case of Sterility. Inequality be- tween the Son and the Daughter. 61 4 CONTENTS. CHAPTBB FAGS IV. Adoption and Emancipation. 68 V. Kinship. What the Romans called Agnation. 71 -VI. The Right ot Property. VII. The Right of Succession 93 1. Nature and Principle of the Bight of Succes- sion among the Ancients 93 2. The Son, not the Daughter, inherits 96 3. Collateral Succession 100 4. Effects of Adoption and Emancipation. 103 6. Wills were not known originally 104 6. The Right of Primogeniture 107 VIII. Authority in the Family • 1. Principle and Nature of Paternal Powerv among the Ancients Ill 2. Enumeration of the Rights composing the Pa- ternal Power 117 IX. Morals of the Ancient Family 123 X. -

A Re-Examination of the Orthodoxy of Euripides

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1943 A Re-Examination of the Orthodoxy of Euripides Vincent C. Horrigan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Horrigan, Vincent C., "A Re-Examination of the Orthodoxy of Euripides" (1943). Master's Theses. 630. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/630 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1943 Vincent C. Horrigan .,. A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE ORTHODOXY OF EURIPIDES BY VI)JCENT C. HORRIGAN, S.J. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQ,UIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY AUGUST 1943 .' VITA Vlncent C. Horrlgan waa.. born in Mt • Alry, Borth Carollna, November 30, 1916. He attended St. James Parochial Sohool ln Louisvll1e, Kentucky, for elght 7ears, and graduated trODl St. Xavler Hlgh Sohool ln the same 01t7 ln June, 1935. He studled at Harvard Unlver- slt7, Oambrldge, Massachusetts, for one 7ear, after which he entered the Novltlate of the 80c1et7 ot Jesus at Ml1ford, Ohl0, ln September, 1936. The Bachelor of L1tterature degree waa conferred by Xavler Unl verslt7, Clnclnnatl, Ohl0, June, 1940. FrODl 1940 to 1943, the wrlter has been studylng at Weat Baden College, West Baden Sprlngs, Indiana.