Towards an Organizational History of the Philosophy of Marxist-Humanism in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raya Dunayevskaya Papers

THE RAYA DUNAYEVSKAYA COLLECTION Marxist-Humanism: Its Origins and Development in America 1941 - 1969 2 1/2 linear feet Accession Number 363 L.C. Number ________ The papers of Raya Dunayevskaya were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in J u l y of 1969 by Raya Dunayevskaya and were opened for research in May 1970. Raya Dunayevskaya has devoted her l i f e to the Marxist movement, and has devel- oped a revolutionary body of ideas: the theory of state-capitalism; and the continuity and dis-continuity of the Hegelian dialectic in Marx's global con- cept of philosophy and revolution. Born in Russia, she was Secretary to Leon Trotsky in exile in Mexico in 1937- 38, during the period of the Moscow Trials and the Dewey Commission of Inquiry into the charges made against Trotsky in those Trials. She broke politically with Trotsky in 1939, at the outset of World War II, in opposition to his defense of the Russian state, and began a comprehensive study of the i n i t i a l three Five-Year Plans, which led to her analysis that Russia is a state-capitalist society. She was co-founder of the political "State-Capitalist" Tendency within the Trotskyist movement in the 1940's, which was known as Johnson-Forest. Her translation into English of "Teaching of Economics in the Soviet Union" from Pod Znamenem Marxizma, together with her commentary, "A New Revision of Marxian Economics", appeared in the American Economic Review in 1944, and touched off an international debate among theoreticians. -

Harry Mcshane, 1891-1 988

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/hwj/article/27/1/247/643648 by guest on 30 September 2021 Harry McShane, 1891-1 988 Harry McShane was a fragment of history, a unique link with the past. Everybody knows of his friendship with the great Scottish revolutionary socialist, John Maclean; of the fact that he was the last living link with the turbulent time which went down in history booksas 'the revolt of the Clyde'. But, really, it went much further than that. In 1987, though frail and ill, Harry spoke at Glasgow's May Day demonstration. When the first May Day demonstration was held, way back in 1890, Tom Mann, for many years a close friend of Harry McShane, was one of the main speakers. And who was that old man with the white beard, standing at the back of a cart watching the procession as it entered Hyde Park? Yes, the rather podgy man, smiling and saying with satisfaction, 'the grandchildren of the Chartists are entering the stmggle' -who was he? Why, it's none other than Frederick Engels. He knew Tom Mann very well, regarding him as the best working-class militant of the time. Engels also knew another friend of Harry's- a Scottish engineer called John Mahon - and held lengthy discussions with him. Harry McShane, therefore, could draw on comrades with a wonderful fund of knowledge and experience. His friends included some who were prominent in the rise of new unionism in the 1890s. when ordinary working people, not the aristocrats of labour, became organized for the first time. -

''Little Soldiers'' for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics In

IRSH 58 (2013), pp. 71–96 doi:10.1017/S0020859012000806 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis ‘‘Little Soldiers’’ for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics in the British Socialist Sunday School Movement* J ESSICA G ERRARD Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, 234 Queensberry Street, Parkville, 3010 VIC, Australia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper examines the ways in which turn-of-the-century British socialists enacted socialism for children through the British Socialist Sunday School movement. It focuses in particular on the movement’s emergence in the 1890s and the first three decades of operation. Situated amidst a growing international field of comparable socialist children’s initiatives, socialist Sunday schools attempted to connect their local activity of children’s education to the broader politics of international socialism. In this discussion I explore the attempt to make this con- nection, including the endeavour to transcend party differences in the creation of a non-partisan international children’s socialist movement, the cooption of traditional Sunday school rituals, and the resolve to make socialist childhood cultures was the responsibility of both men and women. Defending their existence against criticism from conservative campaigners, the state, and sections of the left, socialist Sunday schools mobilized a complex and contested culture of socialist childhood. INTRODUCTION The British Socialist Sunday School movement (SSS) first appeared within the sanguine temper of turn-of-the-century socialist politics. Offering a particularly British interpretation of a growing international interest in children’s socialism, the SSS movement attempted a non-partisan approach, bringing together socialists and radicals of various political * This paper draws on research that would not have been possible without the support of the Overseas Research Scholarship and Cambridge Commonwealth Trusts, Poynton Cambridge Australia Scholarship. -

The Story of the Historic Scottish Hunger March Harry Mcshane

page 30 • variant • volume 2 number 15 • Summer 2002 The March The story of the historic Scottish hunger march Harry McShane Introduction On Friday, 9th June 1938, along the main roads Originally published in 1933 by the National leading to Edinburgh, columns of men were Unemployed Workers Movement (NUWM) this story marching; men with bands, banners, slogans, eve- relates events seventy years ago. Massive numbers of ryone equipped with knapsack and blanket, their people were out of work in those days, with the field cookers on ahead: an army in miniature, an attendant poverty and misery. unemployed army, the Hunger Marchers. Readers of Three Days That Shook Edinburgh will In the ranks were men of all political opin- themselves feel angry that so little has been done by ions—Labour men, Communists, ILP; there were the labour movement to organise and fight back Trade Unionists and non-Unionists; there were against the ravages of unemployment in the present even sections of women marchers—all marching situation. The daily growing number of unemployed four abreast, shoulder to shoulder, keeping step, are not involved in organising contemporary protest surging along rhythmically. marches to any great degree, and compared to the Here was the United Front of the workers, one of the first fronts of the drive for Unity now being efforts, the imagination and the organisation of the The Hunger March of June 1933, was a coping made in all parts of Britain. NUWM in the thirties they are puny affairs. stone to a whole series of mass activities which In a situation where more than ten people are had swept Scotland. -

Women on Red Clydeside

A RESEARCH COLLECTIONS FINDING AID WOMEN ON RED CLYDESIDE 1910-1920 Alison Clunie Helen Jeffrey Helen Sim MSC Cultural Heritage Studies April 2008 0 Holdings and Arrangement Glasgow Caledonian University’s Research Collections contains diverse and informative material on the subject of women on ‘Red Clydeside’. This material can be found in the following collections: • The Caledonian Collection (CC) • The Centre for Political Song (CPS) • The Gallacher Memorial Library (GML) • The Myra Baillie Archive (MB) • The Norman and Janey Buchan Collection (BC) This finding aid is arranged by subject heading and then alphabetically; it is not arranged by individual collections. The collection where each piece of material can be found is indicated by using the abbreviations shown above. Contents: Pages: Introduction 2 General Material 3-5 Helen Crawfurd 6-7 Mary Barbour 8-9 Other Material 10 Rent Strikes 11-14 Women’s Labour Movement 15-17 Women’s Peace Movement 18 Further information is available from the Research Collections Manager: John Powles ([email protected]) Research Collections (www.gcal.ac.uk/researchcollections/index.html) 1 Introduction The period known commonly as ‘Red Clydeside’, between 1910 and 1920, was an important era of political radicalism. During the First World War the Clyde, and its surrounding area, became an epicentre of ship building and munitions factories. In parallel with these progressions, the area also became the centre of Glasgow’s Labour movement. Male workers on the Clyde were increasingly involved in political activity, such as strikes, rallies and trade unionism. Until recently the role of women within this period of history has been somewhat overlooked. -

Scanned Image

g I anarchist fortnightly FREE CTS WE WELCOME news, reviews, articles, let- SWEDEN ' ters. Copy deadline for next issue (No. 15) is Frihetlige Forum, Landsvagsgatan 19 , MONDAY 31 JULY. A 41304 04 GOTEBORG. Si FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY 29 June - 12 Jul 1978 NEXT DESPATCHING DATE is THURSDAY Vol 39 N014 JULY 22 3 AUGUST. Come and hel from 5 .m. Baden: ABF lnfoburo, Postfach 161, 761 ILFRACOMBE: l.L. 50p;TELFORD: M.A. 50p; (Help also welcomed the previous Tliursday, Schwabisch Hall. NEWCASTLE: .l.M. £ 5; ENFIELD: Z.J. E 5; 27 July for folding Review section). “P Berlin: Anarkistische Bund. Publishers of DENMARK: J.H. 50p; LONDON W7: M.M. _:%_‘I-tin-l"____4 ' Anarkistische Texte ', c/o Libertad Verlag, £ 1; WOLVERHAMPTON: J.L. 5:‘. 1; .l.K.W. I .-up-. Postfach 153, 1000 Berlin 44. 10p; CHEAM: O.L. L. 50p; BRIGHTON: M.C. International 'Gewaltfreie Aktion' (non-violent action) 50p; Anon: £ 3; BLACKBURN: H.M. 50p; DUBLIN: P/D. £ 1; PORTUGAL: J.S. £1.15. @ \l\ll-lllT HUMANS AUSTRALIA groups, throughout FDR, associated WRI , For information write Karl-Heinz Song, . Canberra: Altemative Canberra Group, 10 Total : £ 20.25 Methfesselstr. 69,2000 Hamburg 19. Previously acknowledged : 5 624.65 Beltana Road, Pialligo, ACT 2809. New South Wgl_§_ Groups in other places: tell us if you want TOTAL to DATE £ 644.90 Black Ram, P.O. Box 238, Darlinghurst, l'O be listed. NSW 2010. , 3 Wm-\r Disintegratorl P.O. Box 291, Bondi Junct- ion, Sydney, NSW, f7 RlG?l4T$ Sydney Anarcho-Syndicalists, Jura Books Col- LONDON. -

JOHN MACLEAN Accuser of Capitalism

JOHN MACLEAN Accuser of Capitalism ‘I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot,’ thundered John Maclean in his famous speech from the dock, in 1918. Acting as his own counsel, Maclean launched a Marxist indictment of the arms trade and the war he believed it had spawned. Biography A fiery and restless teacher, MacLean’s lifelong socialism ‘matured in an instant’1 on the outbreak of war and cemented Red Clydeside’s reputation as a threat to the war effort. MacLean was a bitter opponent of the ‘war madness,’2 stating: ‘every intelligent person now admits that the antagonisms among the nations of Europe that led to the competition of armaments and the present World War was fundamentally due to a universal desire to secure increased empires for the deposit of capital.’3 He captivated outdoor meetings all over Glasgow4 - at the height of his powers addressing five a day5 - and worked alongside others who were more reformist in outlook, such as his friend and fellow teacher, James Maxton. Maclean was an inspiration to the Clyde Workers’ Committee and urged munitions workers to adopt a policy of ‘ca’canny’6 (go-slow) so as not to bolster the arms traders’ profits. But, he later distanced himself from what he saw as the Clyde Workers’ Committee’s narrow focus on shop-floor concerns rather than political opposition to militarism.7 Five terms of imprisonment, including a hunger strike and subsequent force-feeding,8 were compounded by relentless soapboxing in the bitter Glaswegian winter. -

Carrigan, Daniel (2014) Patrick Dollan (1885-1963) and the Labour Movement in Glasgow

Carrigan, Daniel (2014) Patrick Dollan (1885-1963) and the Labour Movement in Glasgow. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5640 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] PATRICK DOLLAN(1885-1963) AND THE LABOUR MOVEMENT IN GLASGOW Daniel Carrigan OBE B.A. Honours (Strathclyde) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2014 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life and politics of Patrick Dollan a prominent Independent Labour Party (ILP) member and leader in Glasgow. It questions the perception of Dollan as an intolerant, Irish-Catholic 'machine politician' who ruled the 'corrupt' City Labour movement with an 'iron fist', dampened working-class aspirations for socialism, sowed the seeds of disillusionment and stood in opposition to the charismatic left-wing MPs such as James Maxton who were striving to introduce policies that would eradicate unemployment and poverty. Research is also conducted into Dollan's connections with the Irish community and the Catholic church and his attitude towards Communism and communists to see if these issues explain his supposed ideological opposition to left-wing movements. -

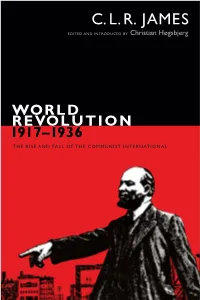

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg. -

''Little Soldiers'' for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics In

IRSH 58 (2013), pp. 71–96 doi:10.1017/S0020859012000806 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis ‘‘Little Soldiers’’ for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics in the British Socialist Sunday School Movement* J ESSICA G ERRARD Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, 234 Queensberry Street, Parkville, 3010 VIC, Australia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper examines the ways in which turn-of-the-century British socialists enacted socialism for children through the British Socialist Sunday School movement. It focuses in particular on the movement’s emergence in the 1890s and the first three decades of operation. Situated amidst a growing international field of comparable socialist children’s initiatives, socialist Sunday schools attempted to connect their local activity of children’s education to the broader politics of international socialism. In this discussion I explore the attempt to make this con- nection, including the endeavour to transcend party differences in the creation of a non-partisan international children’s socialist movement, the cooption of traditional Sunday school rituals, and the resolve to make socialist childhood cultures was the responsibility of both men and women. Defending their existence against criticism from conservative campaigners, the state, and sections of the left, socialist Sunday schools mobilized a complex and contested culture of socialist childhood. INTRODUCTION The British Socialist Sunday School movement (SSS) first appeared within the sanguine temper of turn-of-the-century socialist politics. Offering a particularly British interpretation of a growing international interest in children’s socialism, the SSS movement attempted a non-partisan approach, bringing together socialists and radicals of various political * This paper draws on research that would not have been possible without the support of the Overseas Research Scholarship and Cambridge Commonwealth Trusts, Poynton Cambridge Australia Scholarship. -

Remembering Scottish Communism

Gibbs, E. (2020) Remembering Scottish Communism. Scottish Labour History, 55, pp. 83-106. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/227600/ Deposited on: 8 January 2021 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Remembering Scottish Communism Ewan Gibbs Scottish Labour History vol.55 (2020) pp.83-106 Introduction The centenary of the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1920 provides an opportunity to assess its memory and legacy in Scotland. For seventy-one years, the CPGB’s presence within the Scottish labour movement ensured the continuity of a distinctive political culture as well as an enduring connection with the Third International’s world-historic project. The party was disproportionately concentrated on Clydeside and in the Fife coalfields, which were among its most significant strongholds across the whole of Britain. These were areas where the CPGB achieved some of its rare local and parliamentary electoral successes but also more importantly centres of enduring strength within trade unionism and community activism. Engineers and miners emerged as the party’s key public representatives in Scotland. Their appeal rested on a form of respectable working-class militancy that radiated authenticity drawn from workplace experience and standing in local communities. Abe Moffat, the President of the Scottish miners’ union between 1942 and 1961, articulated this sentiment by explaining to Paul Long in 1974 that: ‘I used to smile when I heard right-wing leaders saying that the Communists were infiltrating into the trade union: we’d been there all our lives.’1 Even within the coalfields, activists such as Moffat were part of a militant minority. -

Communists Text

The University of Manchester Research Communists and British Society 1920-1991 Document Version Proof Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K., Cohen, G., & Flinn, A. (2007). Communists and British Society 1920-1991. Rivers Oram Press. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 INTRODUCTION A dominant view of the communist party as an institution is that it provided a closed, well-ordered and intrusive political environment. The leading French scholars Claude Pennetier and Bernard Pudal discern in it a resemblance to Erving Goffman’s concept of a ‘total institution’. Brigitte Studer, another international authority, follows Sigmund Neumann in referring to it as ‘a party of absolute integration’; tran- scending national distinctions, at least in the Comintern period (1919–43) it is supposed to have comprised ‘a unitary system—which acted in an integrative fashion world-wide’.1 For those working within the so-called ‘totalitarian’ paradigm, the validity of such ‘total’ or ‘absolute’ concep- tions of communist politics has always been axiomatic.