Self-Assembly of Multi-Component Mitochondrial Nucleoids Via Phase Separa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Genomes Viral Genomes Prokaryotic Genome

The nature of genomes • Genomics: study of structure and function of genomes • Genome size – variable, by orders of magnitude – number of genes roughly proportional to genome size • Plasmids – symbiotic DNA molecules, not essential – mostly circular in prokaryotes • Organellar DNA – chloroplast, mitochondrion – derived by endosymbiosis from bacterial ancestors Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company Viral genomes • Nonliving particle In prokaryotes, viruses are – nucleic acid sometimes referred to as – protein bacteriophages. • DNA or RNA – single-stranded or double-stranded – linear or circular • Compact genomes with little spacer DNA Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company Prokaryotic genome • Usually circular double helix – occupies nucleoid region of cell – attached to plasma membrane • Genes are close together with little intergenic spacer • Operon – tandem cluster of coordinately regulated genes – transcribed as single mRNA • Introns very rare Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. Freeman and Company 1 Eukaryotic nuclear genomes • Each species has characteristic chromosome number • Genes are segments of nuclear chromosomes • Ploidy refers to number of complete sets of chromosomes –haploid (1n): one complete set of genes – diploid (2n) – polyploid (≥3n) • In diploids, chromosomes come in homologous pairs (homologs) In humans, somatic cells have – structurally similar 2n = 46 chromosomes. – same sequence of genes – may contain different alleles Chapter 2: Genes and genomes © 2002 by W. H. -

Chapter 4 – Cell Structure

Chapter 4 | Cell Structure 107 4 | CELL STRUCTURE Figure 4.1 (a) Nasal sinus cells (viewed with a light microscope), (b) onion cells (viewed with a light microscope), and (c) Vibrio tasmaniensis bacterial cells (seen through a scanning electron microscope) are from very different organisms, yet all share certain basic cell structure characteristics. (credit a: modification of work by Ed Uthman, MD; credit b: modification of work by Umberto Salvagnin; credit c: modification of work by Anthony D'Onofrio, William H. Fowle, Eric J. Stewart, and Kim Lewis of the Lewis Lab at Northeastern University; scale-bar data from Matt Russell) Chapter Outline 4.1: Studying Cells 4.2: Prokaryotic Cells 4.3: Eukaryotic Cells 4.4: The Endomembrane System and Proteins 4.5: The Cytoskeleton 4.6: Connections between Cells and Cellular Activities Introduction Close your eyes and picture a brick wall. What is the wall's basic building block? It is a single brick. Like a brick wall, cells are the building blocks that make up your body. Your body has many kinds of cells, each specialized for a specific purpose. Just as we use a variety of materials to build a home, the human body is constructed from many cell types. For example, epithelial cells protect the body's surface and cover the organs and body cavities within. Bone cells help to support and protect the body. Immune system cells fight invading bacteria. Additionally, blood and blood cells carry nutrients and oxygen throughout the body while removing carbon dioxide. Each of these cell types plays a vital role during the body's growth, development, and day-to-day maintenance. -

The Mitochondrial Genome. the Nucleoid

ISSN 0006-2979, Biochemistry (Moscow), 2016, Vol. 81, No. 10, pp. 1057-1065. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2016. Original Russian Text © A. A. Kolesnikov, 2016, published in Biokhimiya, 2016, Vol. 81, No. 10, pp. 1322-1331. REVIEW The Mitochondrial Genome. The Nucleoid A. A. Kolesnikov Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Biology, 119991 Moscow, Russia; E-mail: [email protected] Received May 30, 2016 Revision received July 1, 2016 Abstract—Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in cells is organized in nucleoids containing DNA and various proteins. This review discusses questions of organization and structural dynamics of nucleoids as well as their protein components. The structures of mt-nucleoid from different organisms are compared. The currently accepted model of nucleoid organization is described and questions needing answers for better understanding of the fine mechanisms of the mitochondrial genetic apparatus functioning are discussed. DOI: 10.1134/S0006297916100047 Key words: mitochondrial nucleoid, mitochondrial genome It is now clear that understanding of genome organ- mtDNA). In fact, proteins associated with a nucleoid can ization of subcellular structures is necessary for under- influence the speed of accumulation of mutations. standing of cellular processes occurring through the cell In the last decade, reviews devoted to this subject cycle, including questions of storage, realization, and appeared regularly [5-9]. Generally, they cover the subject transmission of genetic information. A considerable of nucleoid organization in metazoan mitochondria amount of information about forms and sizes of mito- (mainly in human cells) and fungi (mainly yeast). chondrial DNA (mtDNA) throughout evolution has been Reviews touching plant cells are much less frequent [10, accumulated [1]. -

Basic Features of All Cells

Plasma Lab 4 membrane Basic Semifluid Ribosomes features substance (make called proteins) of all cytosol cells Chromosomes (carry genes) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Prokaryotic cells are characterized by having . No nucleus . DNA in an unbound region called the nucleoid . No membrane-bound organelles . Cytoplasm bound by the plasma membrane © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Eukaryotic cells are characterized by having • DNA in a nucleus that is bounded by a membranous nuclear envelope • Membrane-bound organelles • Cytoplasm in the region between the plasma membrane and nucleus Eukaryotic cells are generally much larger than prokaryotic cells © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 6.8a ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM (ER) Nuclear envelope Rough ER Smooth ER Nucleolus NUCLEUS Flagellum Chromatin Centrosome Plasma membrane CYTOSKELETON: Microfilaments Intermediate filaments Microtubules Ribosomes Microvilli Golgi apparatus Peroxisome Lysosome Mitochondrion © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 6.8b Nuclear envelope NUCLEUS Nucleolus Rough ER Chromatin Smooth ER Ribosomes Golgi Central vacuole apparatus Microfilaments CYTOSKELETON Microtubules Mitochondrion Peroxisome Plasma Chloroplast membrane Cell wall Plasmodesmata Wall of adjacent cell © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Table 6.1 © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. Cell Walls of Plants The cell wall is an extracellular structure that distinguishes plant cells from animal cells Plant cell walls Prokaryotes, are made -

Coli Chromosome Into a Nucleoid Filament

Strong intranucleoid interactions organize the Escherichia coli chromosome into a nucleoid filament Paul A. Wigginsa,1, Keith C. Cheverallsa,b, Joshua S. Martina,b, Robert Lintnera, and Jané Kondevb aWhitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, 9 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142; and bMartin A. Fisher School of Physics, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02453 Edited by Nancy E Kleckner, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved January 27, 2010 (received for review October 26, 2009) The stochasticity of chromosome organization was investigated by Our quantitative measurements of E. coli nucleoid structure con- fluorescently labeling genetic loci in live Escherichia coli cells. In firm this qualitative picture: The body of the nucleoid is linearly spite of the common assumption that the chromosome is well organized along the long-axis of the cell, implying that the modeled by an unstructured polymer, measurements of the locus nucleoid has a nearly-constant linear packing density, except distributions reveal that the E. coli chromosome is precisely orga- for a short region, genomically ter-proximate, which connects nized into a nucleoid filament with a linear order. Loci in the body the two arms of the chromosome (11). But in spite of the obser- of the nucleoid show a precision of positioning within the cell of vation of a linear chromosome organization in both E. coli and better than 10% of the cell length. The precision of interlocus dis- C. crescentus, the mechanism which gives rise to this characteristic tance of genomically-proximate loci was better than 4% of the cell structure is unknown. length. The measured dependence of the precision of interlocus To probe the mechanism of nucleoid organization, we measure distance on genomic distance singles out intranucleoid interactions and analyze the position fluctuations of single loci and the cor- as the mechanism responsible for chromosome organization. -

The Chloroplast Nucleoid in Ochromonas Danica I

J. Cell Sci. 16, 557-577 0974) 557 Printed in Great Britain THE CHLOROPLAST NUCLEOID IN OCHROMONAS DANICA I. THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY IN LIGHT- AND DARK-GROWN CELLS SARAH P. GIBBS, D. CHENG AND T. SLANKIS Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal HT,C 3G1, Canada SUMMARY The 3-dimensional structure of the plastid nucleoid was determined from serial sections of the plastid of dark-grown, greening, and light-grown cells of Ochromonas danica. In light- grown and greening cells, the chloroplast nucleoid forms a continuous cord or ring which closely follows the rim of each lateral lobe of the chloroplast and is continuous across the top and bottom of the bridge connecting the 2 chloroplast lobes. The nucleoid always lies just inside the chloroplast girdle bands where they loop around the rim of the plastid. It was demonstrated by electron-microscopic autoradiography of greening cells labelled with [3H]- thymidine that all the plastid DNA is localized in this peripheral ring-shaped nucleoid. In the proplastid of dark-grown cells, the nucleoid also forms a ring-shaped structure lying just inside the single girdle thylakoid, although frequent irregularities, such as gaps, are present. It is postulated that the girdle bands determine the shape of the chloroplast nucleoid, possibly by having specific attachment sites for the plastid DNA molecules. A survey of the literature shows that a peripheral ring-shaped chloroplast nucleoid is a characteristic feature of the 5 classes of algae whose chloroplasts possess girdle bands, namely the Raphidophyceae, Chryso- phyceae, Bacillariophyceae, Xanthophyceae, and Phaeophyceae, and has never been observed in plants whose plastids lack girdle bands. -

In Situ Imaging of Mitochondrial Translation Shows Weak Correlation

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2017) 130, 4193-4199 doi:10.1242/jcs.206714 TOOLS AND RESOURCES In situ imaging of mitochondrial translation shows weak correlation with nucleoid DNA intensity and no suppression during mitosis Christopher Estell1, Emmanouela Stamatidou2, Sarah El-Messeiry2,3 and Andrew Hamilton2,* ABSTRACT not been tested because no method exists to examine total de novo Although mitochondrial translation produces only 13 proteins, we show mitochondrial genome and expression simultaneously in situ here how this process can be visualised and detected in situ . Mitochondrial genome polymorphisms (heteroplasmy) is by fluorescence microscopy with a simple, rapid and inexpensive also common in mammalian cells (Larsson, 2010; He et al., 2010), procedure using non-canonical amino acid labelling and click partly due to the much higher mutation rate of mitochondrial DNA chemistry. This allows visualisation of the translational output in compared to nuclear DNA (Taylor et al., 2003) but, again, it is not different mitochondria within a cell, their position within that cell and a known how such sequence variation affects overall genome comparison of mitochondrial translation between cells. The most highly expression. Heterogeneity of mitochondrial membrane potential translationally active mitochondria were closest to the nucleus but were and activity of some mitochondrial enzymes have been observed also found at the distal end of long cellular projections. There were and associated with disease (Wikstrom et al., 2009), in a way similar substantial differences in translation between adjacent mitochondria to that of genetic polymorphism. However, the extent to which and this did not readily correlate with apparent mitochondrial genome such physiological heterogeneity arises from mitochondrial gene content. -

Microgametophytic Plastid Nucleoid Content and Reproductive and Life History Traits of Tribe Trifolieae (Fabaceae)

Plant P1. Syst. Evol. 196:89-98 (1995) Systematics and Evolution '© Springer-Verlag 1995 Printed in Austria Microgametophytic plastid nucleoid content and reproductive and life history traits of tribe Trifolieae (Fabaceae) R. N. KEYS, S. E. SMITH, H. LLOYD MOOENSEN, and E. SMALL Received August 2, 1994; in revised version September 28, 1994 Key words: Leguminosae, Medicago, alfalfa. - Microgametophyte, biparental inheri- tance, DAPI. Abstract: Microgametophytic plastid nucleoids were quantified for 18 species represent- ing the four core genera of the tribe Trifolieae (Fabaceae), Medicago, Melilotus, Trigonel- la, and Trifolium. Generative cells of all taxa contained nucleoids, establishing that bipa- rental plastid inheritance is common in the Trifolieae. Nucleoid number and volumes of pollen grains and generative cell nuclei differed among taxa. Nucleoid number was posi- tively correlated with pollen grain and generative cell nuclear volumes, flower size and style length. These relationships disappeared after adjusting nucleoid number for pollen grain and generative cell nuclear volumes. Adjusted nucleoid numbers provided no evi- dence to support hypotheses that plastid content is associated with ploidy level, mating system, perenniality or size of the reproductive apparatus. Advances in cytology and molecular biology have stimulated interest in describ- ing the mode of organelle inheritance in plants. Data from a number of studies have shown that the assumption of strict maternal inheritance of plastids in angio- sperms is not justified (review in HARRIS • INGRAM 1991). Using the DNA fluo- rochrome DAPI (4'-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), CORRIVEAU & COLEMAN (1988) analyzed generative or sperm cells from 235 angiosperm species for the presence of plastid nucleoids (DNA aggregates) and found cytological evidence for poten- tial paternal inheritance of plastids in 43 species from 26 genera. -

The Mitochondrial Nucleoid: Integrating Mitochondrial DNA Into Cellular Homeostasis

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The Mitochondrial Nucleoid: Integrating Mitochondrial DNA into Cellular Homeostasis Robert Gilkerson1,2, Liliana Bravo1, Iraselia Garcia1, Norma Gaytan1, Alan Herrera1, Alicia Maldonado2, and Brandi Quintanilla1 1Department of Biology, University of Texas-Pan American, Edinburg, Texas 78539-2999 2Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, University of Texas-Pan American, Edinburg, Texas 78539-2999 Correspondence: [email protected] The packaging of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into DNA-protein assemblies called nucle- oids provides an efficient segregating unit of mtDNA, coordinating mtDNA’s involvement in cellular metabolism. From the early discovery of mtDNA as “extranuclear” genetic material, its organization into nucleoids and integration into both the mitochondrial organellar network and the cell at large via a variety of signal transduction pathways, mtDNA is a crucial component of the cell’s homeostatic network. The mitochondrial nucleoid is com- posed of a set of DNA-binding core proteins involved in mtDNA maintenance and transcrip- tion, and a range of peripheral factors, which are components of signaling pathways controlling mitochondrial biogenesis, metabolism, apoptosis, and retrograde mitochon- dria-to-nucleus signaling. The molecular interactions of nucleoid components with the organellar network and cellular signaling pathways provide exciting clues to the dynamic integration of mtDNA into cellular metabolic homeostasis. ORIGINS: “EXTRANUCLEAR DNA” AND later confirmed by the similarity of mtDNA to BIOENERGETICS bacterial, rather than human nuclear, DNA. This “extranuclear” DNA is in fact essential for istorically, it has been clear that mitochon- mitochondrial ATP production (DiMauro and Hdria play by theirown rules. -

A Bacteriophage Tubulin Harnesses Dynamic Instability to Center DNA In

RESEARCH ARTICLE elifesciences.org A bacteriophage tubulin harnesses dynamic instability to center DNA in infected cells Marcella L Erb1†, James A Kraemer2†, Joanna K C Coker1, Vorrapon Chaikeeratisak1, Poochit Nonejuie1, David A Agard2*, Joe Pogliano1* 1Division of Biological Sciences, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 2Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States Abstract Dynamic instability, polarity, and spatiotemporal organization are hallmarks of the microtubule cytoskeleton that allow formation of complex structures such as the eukaryotic spindle. No similar structure has been identified in prokaryotes. The bacteriophage-encoded tubulin PhuZ is required to position DNA at mid-cell, without which infectivity is compromised. Here, we show that PhuZ filaments, like microtubules, stochastically switch from growing in a distinctly polar manner to catastrophic depolymerization (dynamic instability) both in vitro and in vivo. One end of each PhuZ filament is stably anchored near the cell pole to form a spindle-like array that orients the growing ends toward the phage nucleoid so as to position it near mid-cell. Our results demonstrate how a bacteriophage can harness the properties of a tubulin-like cytoskeleton for efficient propagation. This represents the first identification of a prokaryotic tubulin with the dynamic instability of microtubules and the ability to form a simplified bipolar spindle. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.03197.001 *For correspondence: agard@ msg.ucsf.edu (DAA); jpogliano@ ucsd.edu (JP) †These authors contributed Introduction equally to this work Tubulins are universally conserved GTPases that polymerize in a head to tail fashion to form filaments. -

Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Inquire: Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells Overview Unlike prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells have: 1) a membrane-bound nucleus; 2) numerous membrane-bound organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, chloroplasts, mitochondria, and others; and 3) several, rod-shaped chromosomes. Because a membrane surrounds a eukaryotic cell’s nucleus, it has a “true nucleus.” The word “organelle” means “little organ,” and as we already mentioned, organelles have specialized cellular functions, just as your body's organs have specialized functions. At this point, it should be clear that eukaryotic cells have a more complex structure than prokaryotic cells. Organelles allow different functions to be compartmentalized in different areas of the cell. Big Question: What are the functions of the major cell structures? Watch: Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Have you ever heard the phrase “form follows function?” It’s a philosophy that many industries follow. In architecture, this means that buildings should be constructed to support the activities that will be carried out inside them. For example, a skyscraper should include several elevator banks. A hospital should have its emergency room easily accessible. Our natural world also uses the principle of form following function, especially in cell biology. This use will become clear as we explore prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. All cells share four common components: 1) a plasma membrane, an outer covering that separates the cell’s interior from its surrounding environment; 2) cytoplasm, consisting of a jelly-like cytosol within the Biology Module 2 - Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Copyright TEL Library 2018 Page 1 cell in which there are other cellular components; 3) DNA, the cell's genetic material; and 4) ribosomes, which synthesize proteins. -

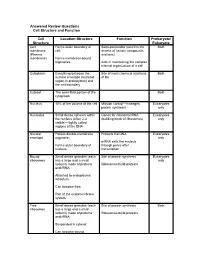

Cell Structure and Function Answered Review SP 08.Pdf

Answered Review Questions Cell Structure and Function Cell Location-Structure Function Prokaryote/ Structure Eukaryote Cell Forms outer boundary of Semi-permeable (restricts the Both membrane cell; access of certain compounds (Plasma and ions) membrane) Forms membrane-bound organelles Aids in maintaining the complex internal organization of a cell Cytoplasm Everything between the Site of most chemical reactions Both nuclear envelope (nucleoid of life region in prokaryotes) and the cell boundary Cytosol The semi-fluid portion of the Both cytoplasm Nucleus 10% of the volume of the cell Mission control—manages Eukaryotes protein synthesis only Nucleolus Small dense spheres within Genes for ribosomal RNA Eukaryotes the nucleus (often 2-3 (building block of ribosomes) only visible)—tightly coiled regions of the DNA Nuclear Porous double-membrane Protects the DNA Eukaryotes envelope organelle; only mRNA exits the nucleus Forms outer boundary of through pores after nucleus transcription Bound Small dense granules (each Site of protein synthesis Eukaryotes ribosomes has a large and a small only subunit) made of proteins Ribosomes build proteins and rRNA; Attached to endoplasmic reticulum; Can become free; Part of the endomembrane system Free Small dense granules (each Site of protein synthesis Both ribosomes has a large and a small subunit) made of proteins Ribosomes build proteins and rRNA; Suspended in cytosol; Can become bound Rough Network of membranous Modify proteins Eukaryotes endoplasmic tubes dotted with bound only reticulum ribosomes; Many proteins are modified here by cleaving the Loosely surrounds the polypeptide, forming quaternary nucleus; structures, removing amino acids or adding non-protein Part of the endomembrane substances (e.g.