DREWS-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (2.532Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS) Handbook 2018 I CONTENTS

FOREWORD This handbook has been produced by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), and is intended for use on ships that are: • compulsorily equipped with GMDSS radiocommunication installations in accordance with the requirements of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea Convention 1974 (SOLAS) and Commonwealth or State government marine legislation • voluntarily equipped with GMDSS radiocommunication installations. It is the recommended textbook for candidates wishing to qualify for the Australian GMDSS General Operator’s Certificate of Proficiency. This handbook replaces the tenth edition of the GMDSS Handbook published in September 2013, and has been amended to reflect: • changes to regulations adopted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) World Radiocommunications Conference (2015) • changes to Inmarsat services • an updated AMSA distress beacon registration form • changes to various ITU Recommendations • changes to the publications published by the ITU • developments in Man Overboard (MOB) devices • clarification of GMDSS radio log procedures • general editorial updating and improvements. Procedures outlined in the handbook are based on the ITU Radio Regulations, on radio procedures used by Australian Maritime Communications Stations and Satellite Earth Stations in the Inmarsat network. Careful observance of the procedures covered by this handbook is essential for the efficient exchange of communications in the marine radiocommunication service, particularly where safety of life at sea is concerned. Special attention should be given to those sections dealing with distress, urgency, and safety. Operators of radiocommunications equipment on vessels not equipped with GMDSS installations should refer to the Marine Radio Operators Handbook published by the Australian Maritime College, Launceston, Tasmania, Australia. No provision of this handbook or the ITU Radio Regulations prevents the use, by a ship in distress, of any means at its disposal to attract attention, make known its position and obtain help. -

Authority and Indemnity in Respect of Telephone, Telex, Fax and E-Mail Instruction (Personal / Joint Account)

Authority and Indemnity in Respect of Telephone, Telex, Fax and E-mail Instruction (Personal / Joint Account) IMPORTANT NOTICE Customers should consider the possible risks inherent in the giving of instructions by telephone, telex, fax or e-mail. Such instructions may be forged and may be transmitted to wrong numbers, may never reach our Bank, may thereby become known to third parties thus losing their confidential nature and may incur other risks. Our Bank accepts no responsibility for the occurrence of any such circumstances or for any action, claim, loss, damage or cost arising or incurred by Customers as a result of or in connection with any such circumstances or the giving of any such instructions by telephone, telex or fax. Customers are and continue to be solely responsible for making their own independent appraisal and assessment of any possible risks in relation to the giving of any such instructions. Accordingly, Customers should not authorize our Bank to accept instructions by telephone, telex, fax or e-mail unless they are prepared to undertake such risks and have satisfied themselves in all respects with regard to such authorization. BDO Unibank, Inc. To : BDO Unibank, Inc. (the “Bank”) From: (the “Customer”)1 /individually and collectively (the “Customer”)2. The Mandate The Customer refers to the mandate (the "Mandate") between the Bank and the Customer governing the operation of all of the Customer's / Firm's* account(s) with the Bank (the "Account(s)") and credit or other facilities or banking arrangements with the Bank. -

Inmarsat-B MOBILE EARTH STATION Models FELCOM 81A/81B

Inmarsat-B MOBILE EARTH STATION Models FELCOM 81A/81B ©Inmarsat and the Inmarsat logo are trademarks of Inmarsat, London, United Kingdom. R ER QUA ST L Catalogue No. W-3237c I IT The future today with FURUNO's electronics technology. G Y E C R O S M « P D A Y N O Y L FURUNO ELECTRIC CO., LTD. L I S O 9 0 0 1 9-52 Ashihara-cho, Nishinomiya City, Japan Telephone: +81 (0)798 65-2111 Telefax: +81 (0)798 65-4200, 66-4622, 66-4623 TRADE MARK REGISTERED FELCOM 81A: (Class 1) GMDSS compatible version FELCOM 81 FELCOM 81B: (Class 2) No-Telex version Inmarsat-B System 178¡E The International Maritime Satellite The Inmarsat space segment consists of Organization (Inmarsat) is a Partnership POR 4 satellites orbiting above the equator of member countries, founded in 1979. at the same speed as the earth With the purpose of providing global rotates. They thus remain fixed communications for ships, land above the same location on the mobile and aircraft, using satellites 35,700 km earth. A satellite orbits at an to overcome the problems that exist altitude of 35,700 km as it sees with conventional radio 1/3 of the earth’s surface. The communications, Inmarsat operates AOR-W satellites work as repeater stations IOR a network consisting of the space 54¡W 64.5¡E between the coast earth stations segment, ground segment and mobile (CESs) and mobile earth stations AOR-E earth stations. (MESs) on different channels for different 15.5¡W services- Inmarsat-A, B, C and M. -

Ethics and Operating Procedures for the Radio Amateur 1

EETTHHIICCSS AANNDD OOPPEERRAATTIINNGG PPRROOCCEEDDUURREESS FFOORR TTHHEE RRAADDIIOO AAMMAATTEEUURR Edition 3 (June 2010) By John Devoldere, ON4UN and Mark Demeuleneere, ON4WW Proof reading and corrections by Bob Whelan, G3PJT Ethics and Operating Procedures for the Radio Amateur 1 PowerPoint version: A PowerPoint presentation version of this document is also available. Both documents can be downloaded in various languages from: http://www.ham-operating-ethics.org The PDF document is available in more than 25 languages. Translations: If you are willing to help us with translating into another language, please contact one of the authors (on4un(at)uba.be or on4ww(at)uba.be ). Someone else may already be working on a translation. Copyright: Unless specified otherwise, the information contained in this document is created and authored by John Devoldere ON4UN and Mark Demeuleneere ON4WW (the “authors”) and as such, is the property of the authors and protected by copyright law. Unless specified otherwise, permission is granted to view, copy, print and distribute the content of this information subject to the following conditions: 1. it is used for informational, non-commercial purposes only; 2. any copy or portion must include a copyright notice (©John Devoldere ON4UN and Mark Demeuleneere ON4WW); 3. no modifications or alterations are made to the information without the written consent of the authors. Permission to use this information for purposes other than those described above, or to use the information in any other way, must be requested in writing to either one of the authors. Ethics and Operating Procedures for the Radio Amateur 2 TABLE OF CONTENT Click on the page number to go to that page The Radio Amateur's Code ............................................................................. -

Glossary – Acronyms, Abbreviations and Terms the Information Contained in This Document Comes from a Variety of Resources

Glossary – Acronyms, Abbreviations and Terms The information contained in this document comes from a variety of resources. This list is representative of acronyms, abbreviations and terms that Amateur Radio communicators may encounter while operating. The list is not all encompassing and has been compiled to reflect items that may be encountered during an emergency response or exercise. AEC – Assistant Emergency Coordinator. A position of leadership within the ARES organization reporting to the EC. Agency Representative – An individual assigned to an incident from an assisting or cooperating agency who has been delegated full authority to make decisions on all matters affecting that agency’s participation at an incident. Agency representatives report to the incident liaison officer. (ICS) Alert – Notification that and emergency situation has occurred, standby for possible activation. Allocated Resources – Resources dispatched to an incident that have not been checked in by the Incident Commander. (ICS) ALS – Advanced Life Support (SAR) AM – Amplitude Modulation. A modulation system where the carrier amplitude is modulated producing equal sidebands or varying amplitude. AMTOR – Amateur Teleprinting Over Radio uses time diversity to minimize the effects of fading. Sent in either ARQ or FEC mode. APRS – Automatic Position Reporting System. A packet based communication system where information from a Global Position Satellite (GPS) is fed to another computer for use. ARC – American Red Cross ARES – Amateur Radio Emergency Service ARQ – Automatic Repeat Request is an AMTOR communication mode where a repeat is sent only when requested by the receiving station. Assigned Resources – Resources checked-in and assigned work tasks on an incident. (ICS) Assisting Agency – An agency directly contributing suppression, rescue, support or services resources to another agency. -

RVON-16 RTS Voice Over Network

RVON-16 RTS Voice Over Network 93507848000 03/2009 Rev D PROPRIETARY NOTICE SHIPPING TO THE MANUFACTURER The product information and design disclosed herein were originated by All shipments of product should be made via UPS Ground, prepaid (you and are the property of Bosch Security Systems, Inc. Bosch reserves all may request from Factory Service a different shipment method). Any patent, proprietary design, manufacturing, reproduction, use and sales shipment upgrades will be paid by the customer. The equipment should rights thereto, and to any article disclosed therein, except to the extent be shipped in the original packing carton. If the original carton is not rights are expressly granted to others. available, use any suitable container that is rigid and of adequate size. If a substitute container is used, the equipment should be wrapped in paper COPYRIGHT NOTICE and surrounded with at least four (4) inches of excelsior or similar shock-absorbing material. All shipments must be sent to the following Copyright 2009 by Bosch Security Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. address and must include the Proof of Purchase for warranty repair. Reproduction, in whole or in part, without prior written permission from Upon completion of any repair the equipment will be returned via Bosch is prohibited. United Parcel Service or specified shipper, collect. WARRANTY NOTICE Factory Service Department Bosch Security Systems, Inc. See the enclosed warranty card for further details. 8601 East Cornhusker Hwy. Lincoln, NE 68507 U.S.A. Attn: Service CUSTOMER SUPPORT This package should include the following: Technical questions should be directed to: Customer Service Department Qty Description Part Number Bosch Security Systems, Inc. -

The Evolution of the International Regulation of the Telegraph Alan J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Odette School of Business Publications Odette School of Business 2015 The cost of a telegram: the evolution of the international regulation of the telegraph Alan J. Richardson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/odettepub Part of the Business Commons, History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Alan J.. (2015). The osc t of a telegram: the evolution of the international regulation of the telegraph. Accounting History. http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/odettepub/84 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Odette School of Business at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Odette School of Business Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The cost of a telegram: the evolution of the international regulation of the telegraph. Alan J. Richardson Odette Research Chair Odette School of Business University of Windsor Windsor Canada. [email protected] The final and definitive version of this article will appear in Accounting History SAGE Publications Ltd, All rights reserved. © [Alan J. Richardson] March 23, 2015. Work on this paper has been supported by an SSHRC grant (410-2010-2231), the Outstanding Scholars program of the University of Windsor, and the research assistants’ program of the Odette MBA program. The research assistance of Colin Wysman, Jason Chen, Paul Borger, Leila Nappi and Austin Dowhan is gratefully acknowledged. -

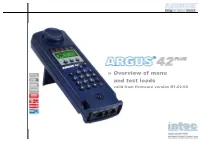

Overview of Menu and Test Leads Valid from Firmware Version R1.02.00

» Overview of menu and test leads valid from firmware version R1.02.00 Legend, Hotkeys – page 3 – Cross references: ADSL / Ethernet S / U / POTS interface Menu Menu Seite d n Configuration menu Key ADSL Ethernet Key S / U POTS Access 4 e g Default Config. menu e Main menu 5 L Input menu 0 Argus status 0 Argus status Single tests 5 Default input menu 1 Help hotkeys 1 Help hotkeys Test reports 5 2 VPI/VCI scan - 2 Service check - Settings 6 3 IP ping 3 Supp. Serv. test - Device 6 4 - 4 Auto. test s y Profiles 7-8 e 5 HTTP download 5 Test to PC k t ISDN 9 o 6 - - 6 Test manager - POTS 9 H 7 - - 7 Numbers Accu servicing 5 8 Trace/remote 8 Trace/remote Help 5 9 - - 9 BERT start - IP and ATM tests Seite ∏ Line-Status ∏ Level measuring IP ping 10 VoIP phone Connection HTTP download *0 Access selection *0 Access selection VPI/VCI scan 11 ATM OAM ping *1 SW options *1 SW options VoIP 12 *2 Reset *2 Reset MDI analysis 13 Ethernet loop ISDN tests Seite BERT Supp. services 14 Services X.31 15 CF tests 16 Phone / connect. 17 Auto. Test 18 Other tests Seite Phone / Connect.. 5 (POTS) Copper test 19 Other Seite Legend 3 Hotkeys 3 Test leads 20-21 ® PLUS e t The basic package of an ARGUS 42 always includes the ADSL interface. All the rest of the interfaces and test features o N are optional (see options in datasheet). Subject to the opted function range therefore individual menu options can be faded out. -

Communication in Dis

Indexed DC 6 15 DISASTER COMMUNICATIONS PART 1 GLOBAL First Edition, June 1996 Mark Wood, G4HLZ Disaster Relief Communications Foundation Table of Contents 1 Global 1.1 Introduction 1.1.2 What Is 'Disaster Communications' 1.1.3 Differences to 'Aid' 1.1.4 Emergency Services 1.2 What Do We Want? 1.2.1 For Phone 1.2.2 Against Phone 1.2.3 For Text 1.2.4 Against Text 1.2.5 For Fax 1.2.6 Against Fax 1.2.7 Semi-fax 1.2.8 ISDN 1.2.9 Internet Electronic Mail 1.2.10 World Wide Web (WWW) 1.3 Networks 1.3.1 Trafficking Messages 1.3.2 Keeping a Log 1.3.3 Echo Tests 1.3.4 Summary 2 Satellite Systems 2.1 The Inmarsat System 2.1.1 For Inmarsat-A 2.1.2 Against Inmarsat-A 2.1.3 Inmarsat-B 2.1.4 For Inmarsat-C 2.1.5 Against Inmarsat-C 2.1.6 For Inmarsat-M http://www.reliefweb.int/library/dc1/dcc1.html (1 von 21) [10.01.2000 23:09:30] Indexed DC 6 15 2.1.7 Against Inmarsat-M 2.1.8 Data over Inmarsat 2.2 Fleet Management Systems 2.3 Regional Satellite Systems 2.4 The Leo Systems 2.5 Satellite Dispatcher Systems 3 HF Radio 3.1 Introduction 3.1.2 HF Radio Equipment 3.1.2.1 Modulation Modes 3.1.3 Antennas 3.1.3.1 ATUs 3.1.4 Dipoles 3.1.4.1 Widebanders 3.1.5 Verticals 3.1.6 Beams 3.1.7 Loops 3.1.8 Multi Antenna Systems 3.2 Marine Radio 3.2.2 How It Is Used 3.2.3 For Marine Radio 3.2.4 Against Marine Radio 3.2.5 For Autolink 3.2.6 Against Autolink 3.3 Gateway Services 3.3.1 For Gateway 3.3.2 Against Gateway 3.4 Amateur Radio Service 3.4.1 Resolution 640 3.4.2 For Amateur Radio 3.4.3 Against Amateur Radio 3.5 'Private' HF Radio Networks 4 Power 4.1.1 Batteries -

Development of Automatic Telegraph Switching Systems

UNCLASSIFIED Development of Automatic Telegraph Switehing Systems BY R. D. PARKER Uncla.ssijied There are two general types of automat~ !elegraph switd1£ng systtms. In one, eUctrieal circuits are e.st.ablished to pr1Jvidt comnmnicatWn patht between lelegra'[Jh silJti-Ons in customers' o.flic~ and are broken wMn t.ltt need for communication is over. In the other, direct tllectrical circuits between stations are not established, but coded informatiott in messages automatically routes them through telegraph networks to their dBStino,tions. This paper de.scribes briefly same of the systems now in use, and oldliTUs some of the requirements whic.h had to be met to provide a sali-Ojadory seniice. INTRODUCTION A switch as used in electrical engineering is defined in dictionaries as a device for making, breaking, or changing the connections in an electric circuit. When a switching operation is performed, circuits are changed from one connection to another and devices are cut in and out of circuits. The idea is to transfer or shift these electrical circuits and devices around. A telephone et:>atral office or exchange is an excellent example of the above, in that e\ectrical voke-tran.smission circuits are shifted about to establish commuoication paths between parties, and are broken when conversations are over. Thus, a telephone exchange area such as the District of Columbia is operated as a large ele(trical switching system. Telegraph circuits are established, broken, and shifted around like telephone circuits, and when telegraph circuits t0 subscribern' premises ate connected and disconnected on reque;ts from subscribers a telegraph exchange system is created. -

Telex Radio Dispatch, Part of the Bosch Group, Manufactures and Delivers Thousands of Mission-Critical Communication Systems Worldwide

Innovating the Future of Mission-Critical Communications More installations than any other IP-based dispatch system. Table of Contents Features: IP-based FAQ 4 Nexus IP Console Position – complete communications solution 5 C-Soft – software-based radio dispatch console 6 DFSI-P25 7 Advanced SIP – session initiation protocol (SIP) 8 Beacon Series – includes Advanced Digital Headset Box (ADHB-4) and Remote Headset Box (RHB) 9 Telex C-Soft 10 IP-224 11 IP-223 12 MTRBi - Radio Interface for C-Soft 13 Accessories 14 Network Recorder 15 Remote Database Reviewer Telex System Manager (TSM) 16 V.I.P.E.R. – IP-based radio control system IP-1616 – eight-line IP-based radio dispatch console 17 C-6200 – 18-line IP/analog radio dispatch console 18 IP-2002 – two-line IP-based radio dispatch console C-1616 – six-line analog tone remote control console 19 C-2002 – two-line radio control console 20 C-2000 & C-2000HS – single-line radio control console 21 DSP-223 & TRA-223– tone remote adapter panel 22 Headsets – includes DH2000, DH2200, DH3000, and DH3200 Microphones – includes MDMS, 6513C, DT-GN-18, and PC desktop-18RD 23 System Diagram 24 2 | www.telex.com/radiodispatch Telex Radio Dispatch, part of the Bosch Group, manufactures and delivers thousands of mission-critical communication systems worldwide. Telex Radio Dispatch is the leading manufacturer of IP control Recorder, paging, and intercom. Available features include for two-way radio communications. Based on a distributive Fleetsync, MDC-1200, and Advanced SIP. C-Soft is compatible architecture, Telex dispatch console systems have flexibility, and Windows 7 32- and 64-bit formats. -

C-SOFT IP DISPATCH CONTROL Application for Any Dispatch Environment

WORKS FOR YOU C-Soft is the industry’s most flexible and capable software dispatch console and is the perfect C-SOFT IP DISPATCH CONTROL application for any dispatch environment. C-Soft delivers all of the dispatch capabilities you expect while also giving you the flexibility that only an IP-based software console can provide: simple and quick deployment in the field, easy back-up of communications assets, and the ability to save multiple configurations on a single computer. This proven application has been deployed in communication centers around the world in applications from 911 dispatch to mobile command centers and transportation management. PRODUCT INFORMATION BASE DISPATCH SOFTWARE OPTIONAL FEATURES* SAP # Description SAP # Description F.01U.307.023 C-Soft 2-line Software v7 F.01U.307.047 SIP 6-line C-Soft v7 F.01U.307.024 C-Soft 6-line Software v7 F.01U.307.048 SIP 12-line C-Soft v7 F.01U.307.025 C-Soft 12-line Software v7 F.01U.307.042 P25 DFSI Direct IP 2-line F.01U.307.026 C-Soft 24-line Software v7 F.01U.307.043 P25 DFSI Direct IP 6-line F.01U.307.027 C-Soft 50-line Software v7 F.01U.307.044 P25 DFSI Direct IP 12-line F.01U.307.028 C-Soft 100-line Software v7 F.01U.307.045 P25 DFSI Direct IP 24-line F.01U.307.029 C-Soft 150-line Software v7 F.01U.307.038 Kenwood NEXEDGE Direct IP 2-line F.01U.307.030 C-Soft 200-line Software v7 F.01U.307.039 Kenwood NEXEDGE Direct IP 6-line F.01U.307.031 Upgrade previous C-Soft to C-Soft v7 F.01U.307.040 Kenwood NEXEDGE Direct IP 12-line F.01U.307.041 Kenwood NEXEDGE Direct IP 24-line F.01U.307.032 Per-Line Call Playback 2-line F.01U.307.033 Per-Line Call Playback 6-line F.01U.307.034 Per-Line Call Playback 12-line F.01U.307.035 Per-Line Call Playback 24-line F.01U.307.036 Per-Line Call Playback 50-line Bosch Security Systems, Inc.