20 Years of Scandinavian Studies at Vilnius University – Feast, Play and Puzzles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jag Blev Glad(Are) Och Vis(Are) Unga Vuxnas Läsning Av Skönlitteratur

MAGISTERUPPSATS I BIBLIOTEKS OCH INFORMATIONSVETENSKAP VID BIBLIOTEKS- OCH INFORMATIONSVETENSKAP/BIBLIOTEKSHÖGSKOLAN 2005:119 ISSN 1404-0891 Jag blev glad(are) och vis(are) Unga vuxnas läsning av skönlitteratur EVA RANGLIN MARIANNE TENGFJORD © Författarna Mångfaldigande och spridande av innehållet i denna uppsats – helt eller delvis – är förbjudet utan medgivande. Svensk titel: Jag blev glad(are) och vis(are): Unga vuxnas läsning av skönlitteratur English title: I became happier and wiser: young adults reading of fiction Författare: Eva Ranglin & Marianne Tengfjord Kollegium: Kollegium 3 Färdigställt: 2005 Handledare: Gunilla Borén, Skans Kersti Nilsson, Christian Swalander Abstract: This Master’s thesis explores young adults’ 18-26 years old, reading of fiction: their reading preferences, the meaning of reading and their access to literature. A study was made by way of a questionnaire, including 56 young adults, and seven qualitative interviews with two groups: one at a folk high- school and the other at a public library. The theories we have used to analyse the results are: theories of gender and youth, theories of literary genres, reader-response criticism, literature sociology and the theories of cultural sociology by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In the analysis the results are compared to other studies of reading habits. Results from this study show that the young adults read fiction from several genres among popular- and quality literature. Women read more than men and they read fiction by male and female authors. Men are in favour of male authors. Women read more genres than men do and many women prefer reading realistic stories about people’s tragic fortunes. Most of the respondents read fiction for entertainment, for emotional and/or existential causes and for general knowledge. -

Charlotte Barslund Has Translated Several Norwegian and Danish Writers, Including Jo Nesbø and Karin Fossum

Vigdis Hjorth (born 1959) is a Norwegian novelist whose work has been recognised by many prizes. She writes about the dilemmas of living in modern society; her characters struggle to come to terms with a rapidly changing world and to find a meaningful way to integrate with others and realise their own potential. In this novel she combines the political with the personal, as she also does in Snakk til meg (Talk To Me, 2010), about the problems of a long-distance intercultural relationship, and Leve Posthornet! (Long Live the Postal Service! 2012), which examines the clash between local, ‘people-friendly’ services and global corporations. Her latest novel, Arv og miljø (Inheritance and Environment, 2016), a searing account of sexual abuse, has aroused heated debate about the relationship between fiction and reality. Charlotte Barslund has translated several Norwegian and Danish writers, including Jo Nesbø and Karin Fossum. Her translation of Per Petterson’s I Curse the River of Time was shortlisted for the Independent 2011 Foreign Fiction award, and that of Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned was nominated for the 2016 International Dublin Literary Award. Some other books from Norvik Press Kjell Askildsen: A Sudden Liberating Thought (translated by Sverre Lyngstad) Jens Bjørneboe: Moment of Freedom (translated by Esther Greenleaf Mürer) Jens Bjørneboe: Powderhouse (translated by Esther Greenleaf Mürer) Jens Bjørneboe: The Silence (translated by Esther Greenleaf Mürer) Hans Børli: We Own the Forest and Other Poems (translated by Louis Muinzer) -

Könsfördelning I Två Läromedel I Ämnet Svenska För Årskurs 9

Beteckning: Institutionen för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap Könsfördelning i två läromedel i ämnet Svenska för årskurs 9. Annakarin Johansson Februari 2009 Examensarbetet/uppsats/30hp/C-nivå Svenska/Litteraturdidaktik LP90/Examensarbet Examinator: Janne Lindqvist Grinde Handledare: Sarah Ljungquist 0 Innehållsförteckning 1. Inledning 2. 1.1 Urval 2. 1.2 Syfte och tes 3. 1.3 Frågeställningar 3. 1.4 Metod 3. 1.5 Begreppen kön och genus 4. 1.6 Begreppet kanon 5. 2. Närläsning av samt urval ur Uppdrag Svenska 3 samt Studio Svenska 4 6. 2.1 Uppdrag Svenska 3 (US3) 6. 2.1.1 Kommentarer till US3 14. 2.2 Studio Svenska 4 (SS4) 18. 2.2.1 Kommentarer till SS4 24. 3. Jämförelse mellan Uppdrag Svenska 3 och Studio Svenska 3 samt slutsats 27. 4. Sammanfattning 31. Litteraturlista 32. 1 1. Inledning När verkligheten ska beskrivas måste den förenklas. Den är helt enkelt för komplex för att beskrivas fullständigt och rättvisande. Detta kan ske genom användning av en modell. Modellen innebär en avgränsning, som i sig innebär att man väljer bort förhållanden eller perspektiv som är betydelsefulla för den totala förståelsen. Det är alltså väldigt viktig hur man "bygger sin modell" och att tala om hur man har gjort, eftersom modellen i sig innebär avsteg från verkligheten. Ett genusperspektivet bidrar till är att justera tidigare medvetna eller omedvetna "modellbyggen" som gör kvinnan till det andra könet1. I strävan mot ett jämställt samhälle är det viktigt att kunna utgå från en bild av verkligheten som är så riktig som möjligt för att kunna åstadkomma en framtida förändring. Litteraturen tecknar bilder av världen och den komplicerade tillvaron ur många erfarenheter, i många former, med många perspektiv. -

Larin Paraske, Finnish Folk Poet

NO. 76 | F AL L 2018 a quarterly publication of the ata’s literary SOURCE division FEATURING NORTHERN LIGHTS LD PROGRAM, ATA 59 CONTEMPORARY SCANDINAVIAN LITERATURE LARIN PARASKE, FINNISH FOLK POET REVIEW: Misha Hoekstra’s translation of the Danish novel Mirror, Shoulder, Signal WORDS, WORDS, WORDS: Our isoisä from Vaasa SOURCE | Fall 2018 1 IN THIS ISSUE FROM THE EDITORS.................................................................3 SUBMISSION GUIDELINES .....................................................4 LETTER FROM THE LD ADMINISTRATOR ..........................5 LD PROGRAM AND SPEAKER BIOS FOR ATA 59................7 READERS’ CORNER.................................................................11 LARIN PARASKE, FINNISH FOLK POET/SINGER by Frances Karttunen..................................................................13 CONTEMPORARY SCANDINAVIAN LITERATURE by Michael Meigs.........................................................................25 REVIEW OF MISHA HOEKSTRA’S TRANSLATION OF MIRROR, SHOULDER, SIGNAL by Dorthe Nors by Michele Aynesworth...............................................................37 WORDS WORDS WORDS COLUMN: Our isoisä from Vaasa..................................................................44 by Patrick Saari BY THE WAY: TOONS by Tony Beckwith........................................................24, 36, 43 CREDITS....................................................................................49 © Copyright 2018 ATA except as noted. SOURCE | Fall 2018 2 From the Editors he Nordic countries -

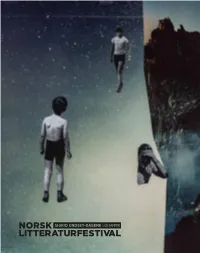

Program 2017

ILLUSTRASJON: KIM HIORTØY • DESIGN: BLÆST DESIGN • TRYKK GRØSET • STEMNINGSBILDER: FESTIVALENS FOTOGRUPPE INNHOLD Høydepunkter 2 t irsdag 30. mai 14 Onsdag 31. mai 20 To rsdag 1. juni 42 Fredag 2. juni 66 Lørdag 3. juni 86 s øndag 4. juni 100 s eminar 108 u tstiLLinger 111 praktisk inFO 115 FOtOkreditering 116 samarbeidspartnere 117 medvirkende 118 kart 120 HØYDEPUNKTER NORSK LITTERATURFESTIVAL SIDE 2 30. MAI 31. MAI 1. JUNI 2. JUNI 3. JUNI 4. JUNI DIN FESTIVAL Norsk Litteraturfestival er Nordens største og Penguin kåret oss nylig til en av de 20 beste litteraturfestivalene i verden! Festivalen gir et unikt overblikk over hva som rører seg i litteraturen akkurat nå. Mer enn 300 SAMFUNNSENGA- forfattere står på scenen. Om du er interessert i SJERT KRIM samfunnsdebatt, poesi eller krim, romaner eller litterær sakprosa; på Lillehammer møter du Den nordiske kriminallittera- et bredt utvalg norske og nordiske forfattere, turen holder høy kvalitet og er sammen med noen av de beste forfatterne fra populær som aldri før. Hvordan hele verden. Vi har invitert forfattere som kan kan det ha seg at vår trygge del bidra til akkurat de samtalene, debattene, av verden, med lav kriminalsta- refleksjonene og kunstopplevelsene vi ønsker tistikk, har blitt et så vellykket at festivalen skal romme. utgangspunkt for å beskrive menneskesinnets irrganger og Noe av det vi har valgt å fokusere på i årets fes- miljøer som bringer svake sjeler tival er indisk litteratur, nasjonalisme, den nor- inn på kriminelle løpebaner? diske litteraturen og såkalt «nature writing». Svenske Johan Theorin og de Vi gleder oss også til å feire Pegasus, festivalens norske krimforfatterne Torkil barne- og ungdomsprogram, som er 10 år i år. -

Modern Greek Studies in the 21St Century

Modern Greek Studies in the 21st Century Panel 1. Elsewheres. Towards less (Pen)insular Modern Greek Studies Georgios Tsagdis (University of Westminster / Leiden University) The 'Elsewheres' of Modern Greek Literature By focusing on one of the most famous poems, from one of the most canonical authors of modern Greek literature, I wish to unravel the problematic of the 'elsewhere'. Cavafy's God Abandons Antony, speaks of emigration, yet in an uncanny reversal it is the city, rather than the person, that emigrates. This 'fleeing of the city', means death, yet it is not only the death of the individual, but the death of an era, of a whole world in demise. Kavafis, who embodies the cultural 'elsewhere' par excellence of modern Greek literature, might enable us orient in a literary and theoretical landscape where everywhere is elsewhere. Alexis Radisoglou (Durham University) Eurozone(s): On Articulating Europe and the Case of Greece Drawing on a larger research project on cultural constructions of a shared and divided sense of ‘Europeanness’, my paper seeks to analyze the ways in which contemporary fiction narrates Europe as a precarious domain for human praxis and political agency. Using Angela Dimitrakaki’s novel Αεροπλάστ (Aeroplast, 2015) as a case study, I focus both on the instantiation of a transnational territoriality in such texts and on their critical negotiation of the question of the possible ‘foundations’ of a shared European imaginary, highlighting different—often highly contentious—forms of contact, transfer and exchange within a plural Europe that transcends the narrowly economistic parameters and unequal power dynamics of the so-called ‘Eurozone’. -

Norske Inspirationer I Dansk Kortprosa

Max Ipsen Norske inspirationer i dansk kortprosa Man kan begynde historien om dansk kortprosa mange steder: de korteste og mindst regulært eventyragtige af H.C. Andersens tekster, fx “Det nye Aarhundredes Musa” eller teksterne i Billedbog uden Billeder, Søren Kierkegaards “Diapsalmata” fra Enten-Eller, Johannes V. Jensens prosaforfatterskab, Peter Seebergs, Raymond Carvers, Ernest Hemmingways. Man kan også lade den begynde med de islandske sagas ordknappe stil, fablen, det romantiske fragment, den amerikanske short story eller short short story’en. Men man kan også lade den begynde i Norge. Det perspek- tiv er der ikke mange der har været opmærksomme på.1 Kortprosamysteriet I nogle år – fra sidste halvdel af 1990’erne til en tre-fire år ind i det nye årtusinde – blev der skrevet en del dansk kortprosa. Og i nogle år – en lille smule, men ikke meget forskudt i forhold til den hektiske kortprosa-produktion – blev der også skre- vet en hel del om dansk kortprosa. Der blev også skrevet kortprosa der kunne læses som kortprosa om kortprosa. Fx skrev Morten Søndergaard i kortprosa-samlingen At holde havet tilbage med en kost (2004) en kort tekst, som man kan læse som et bud på hvor kortprosaen kom fra. Teksten hedder “Foran biblioteket”, og den lyder i sin helhed sådan her: I døråbningen ind til Nationalbiblioteket i Buenos Aires spørger Borges katten som bor der, om han må have lov at gå forbi den. “Det er muligt,” svarer katten, “men du skal vide “ at jeg er mægtig. Og jeg er kun den underste dørvogter; fra sal til sal står der dørvogtere, den ene mægtigere end den anden. -

Program 2019

NORSK LITTERATURFESTIVAL 21. TIL 26. MAI 2019 TIRSDAG NORSK LITTERATURFESTIVAL DAGSPROGRAM SIDE 1 Innhold Guide på veien 2 TirsdaG 21. mai 14 OnsdaG 22. mai 22 TOrsdaG 23. mai 48 FredaG 24. mai 74 LørdaG 25. mai 112 søndaG 26. mai 120 UtsTiLLinGer 127 KOMMA 128 seminarer 130 FotokrediTerinG 134 praKTisK informasjOn 136 samarbeidsparTnere 137 medvirKende og sidereGisTer 138 KarT 140 NORSK LITTERATURFESTIVAL SIDE 2 Nordens største og viktigste Fransk vår litteraturfestival på Lillehammer Breen eller debatt om regionspressen med åreTs prOGram kan vi trygt ved Morten Dahlback, hør si at det er verdt å komme på Norsk maratonopplesning av verdens lengste Litteraturfestival i 2019! Vi har roman; syvbindsklassikeren På sporet som vanlig et håndplukket utvalg av den tapte tid og diskuter litteratur til gode forfattere, i år omtrent 200 lunsj eller ut i de sene nattetimer. Gå på fra 24 nasjoner. Programmet gir Nansenskolens hagefest, drikk kaffe og et unikt innblikk i hva som rører lytt til forfatterne som leser under Lunsj seg i litteraturen akkurat nå. Det i parken og ta med hele familien på det blir debatt og poesi, sakprosa og rikholdige barneprogrammet i helgen. skjønnlitteratur i en frodig blanding. Den franskspråklige litteraturen utgjør Vi oppfordrer deg til å studere et tyngdepunkt i årets festival. Det programmet godt, eller å la oss guide gjør også det norske og det nordiske deg på veien gjennom våre løypeforslag. i en passende blanding av forfattere Hvis du er lur kjøper du billetter i du kjenner fra før og sterke, nye forkant, da kan du rusle rolig fra post bekjentskaper. til post mens alt fokus er rettet mot de Se Han Kang, Édouard Louis og interessante forfattermøtene og den Per Petterson på samme scene under unike stemningen. -

181001 Frankfurt Norla Pressemappe EN.Indd

Press kit for the press conference at Frankfurter Buchmesse 11 October 2018 Press Guest of Honour Organisation Website: www.norway2019.com Krystyna Swiatek and Catherine Knauf NORLA, Norwegian Literature Abroad Facebook: @norwegen2019 c/o Literaturtest PB 1414 Vika, 0115 Oslo, Norway Instagram: @norwegianliterature Adalbertstr. 5 10999 Berlin, Germany Press Books from Norway: Sunniva Adam booksfromnorway.com Phone: +49 (0)30 531 40 70-20 [email protected] NORLA’s website: norla.no Fax: +49 (0)30 531 40 70-99 Phone: +47 23 08 41 00 Email: [email protected] #Norwegen2019 #Norway2019 #norwegianliteratureabroad #thedreamwecarry The digital press kit and images can be found in the press section of our website Contents Norway — The Dream We Carry 5 Olav H. Hauge and the poem 6 Press conference, 11 October 2018 — Programme 7 Speakers at the press conference 8 Statements 11 Frankfurter Buchmesse 2018 — NORLA’s programme 12 Norwegian authors at FBM18 taking part in NORLA’s programme 13 Musicians at the handover ceremony, 14 October 14 The literary programme: The Dream We Carry 15 Norwegian authors to be published in German translation in 2018-2019 16 Cultural programme: The Dream We Carry 18 About NORLA 19 Contact the team 20 Literature in Norway 21 Fiction 21 Crime fiction 22 Non-fiction 22 Children and young adults 23 Sámi literature 25 Languages in Norway 26 The Norwegian literary system 28 Facts and figures for 2017 29 The Guest of Honour project 30 Partners and collaborators 30 4 norway2019.com Norway — The Dream We Carry ‘It is the dream we carry’ of Honour programme. -

Selected Backlist FICTION (5)

Selected backlist FICTION (5) CRIME (29) NON-FICTION (35) Oslo Literary Agency is Norway’s largest literary agency, representing authors in the genres of literary fiction, crime and commercial fiction, children’s and YA books and non-fiction. OKTOBER (49) Oslo Literary Agency was established in 2016, transforming from the in-house Aschehoug Agency to an agency representing authors from a wide range of publishers. In addition, Oslo Literary Agency carries full representation of publisher of literary fiction, Forlaget Oktober. Oslo Literary Agency, Sehesteds gate 3, P. O. Box 363 Sentrum, N-0102 Oslo, Norway osloliteraryagency.no FICTION Maja Lunde (6 - 7) Jostein Gaarder (8 - 9) Simon Stranger (10 - 11) Helga Flatland (12- 13) Carl Frode Tiller (14 - 15) Ketil Bjørnstad (16) Bjarte Breiteig (17) Maria Kjos Fonn (18) Gøhril Gabrielsen (19) Gaute Heivoll (20) Ida Hegazi Høyer (21) Monica Isakstuen (22) Jan Kjærstad (23) Roskva Koritzinsky (24) Thure Erik Lund (25) Lars Petter Sveen (26) Demian Vitanza (27) 5 MAJA LUNDE Praise for The History of Bees: Author of the international bestseller History of Bees, translated into 36 languages “Quite simply the most visionary Norwegian novel I have read since the first instalment of Knausgård’s My Struggle” – Expressen, Sweden “The History of Bees is complex and extraordinarily well-written, and in addition as exciting as a psychological thriller” – Svenska Dagbladet “A first-time novelist who is brave enough to spread out a great, epic canvas and in addition brings up a provocative and current topic, is not something you see every day” – Aftenposten ASCHEHOUG Praise for Blue: “A new bestseller is born (…) Solid and impressive. -

Munch På Tøyen! Planen Om Å Flytte Munch-Museet Fra Tøyen Til Bjørvika Har Vakt Sterk Debatt

pax.no Kamilla Aslaksen og Erling Skaug (red.) Munch på Tøyen! Munch på Planen om å flytte Munch-museet fra Tøyen til Bjørvika har vakt sterk debatt. Også museumskonseptet «Lambda» er svært omstridt. Munch på Tøyen! belyser ulike sider av prosessen rundt flytteplanene: • Hvordan kom flytteideen i stand etter at byrådet i 2005 enstemmig hadde gått inn for nytt mueseum på Tøyen? • Egner «Lambda» seg som kunstmuseum? • Hva koster Bjørvika-planene sammenlignet med en utbygging på Tøyen? • Hvordan kunne juryen velge Lambda når bygget er i konflikt med kommunens egen reguleringsplan? • Hvorfor har kommunen sviktet sitt vedlikeholdsansvar, slik at Munch-museet – idet boken går i trykken – må stenge helt eller delvis pga. klimaproblemer? Munch på Tøyen! Bak boken og oppropet for nytt Munch-museum på Tøyen står en rekke personer fra kulturliv og akademia, Oslo Byes Vel samt beboerforeningene i Tøyen og Gamlebyen. munch på tøyen! 1 2 Kamilla Aslaksen og Erling Skaug (red.) MUNCH PÅ TØYEN! pax forlag a/s, oslo 2011 3 © pax forlag 2011 omslagsillustrasjon: finn graff omslag: akademisk publisering trykk: ait otta as printed in norway isbn 978-82-530-3414-0 boken er utgitt med støtte fra institusjonen fritt ord 4 Innhold Forord | 7 Peter Butenschøn | Den store flyttesjauen i miljøperspektiv | 9 Eivind Otto Hjelle | Glem Fjordbyen – bevar byen! | 15 Rune Slagstad | Nasjonaltyveriet | 21 Morten W. Krogstad m.fl. | Klipp fra pressedebatten | 29 Kamilla Aslaksen og Erling Skaug | Lambda: Musealt behov eller politisk reklamesøyle? | 39 Erling Skaug | Hva koster Lambda? | 59 Jeremy Hutchings og Erling Skaug | Kan Lambda bli et godt museum? | 69 Jeremy Hutchings | Bærekraftige museumsbygg | 83 Thorvald Steen og Jan Erik Vold | Munch og Stenersen må få hvert sitt museum | 103 Didrik Hvoslef-Eide, Harald Hjelle, Stein Halvorsen | Tøyen kan ved enkle grep bli det nye stedet i Oslo, inkludert nytt Munch-museum | 109 Appendiks 1. -

NORD6104 TEORI, SJANGER OG RETORIKK (15 Sp)

Standard pensumliste NORD6104 høsten 2018 NORD6104 TEORI, SJANGER OG RETORIKK (15 sp) Kortere skjønnlitterære tekster (noveller og dikt) er å finne i følgende antologier: Gimnes og Hareide: Norske tekster. Prosa, Cappelen Damm (2009 eller senere) og Stegane, Vinje og Aarseth: Norske tekster. Lyrikk, Cappelen Damm (1998 eller senere). Alle svenske dikt og kortere prosatekster kommer i kompendium. Tekster merket * kommer i kompendium. 1. Episk diktning Fire romaner: . Jonny Halberg: All verdens ulykker (2007) . Knut Hamsun: Sult (1890) . Torborg Nedreaas: Av måneskinn gror det ingenting (1947) . Amalie Skram: Sjur Gabriel (1887) Ca.100 sider kortere prosatekster. *Folkeeventyr: «Østenfor sol og vestenfor måne» (9 s.) . Kjell Askildsen: «Hundene i Tessaloniki» (5 s.) . Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson: «Thrond» (5 s.) . Johan Borgen: «Passet» (9 s.) . Camilla Collett: «Ikke hjemme» (4 s.) . Knut Hamsun: «Livets røst» (4 s.) . Ragnar Hovland: «Seinsommarnattsdraum» (8 s.) . Roy Jacobsen: «Isen» (8 s.) . Liv Køltzow: «I dag blåser det» (8 s.) . Torborg Nedreaas: «Farbror Kristoffer» (7 s.) . Amalie Skram: «Karens Jul» (6 s.) . Tarjei Vesaas: «Det snør og snør» (4 s.) . *Gunnhild Øyehaug: «Liten knute» (8 s) . Hans Aanrud: «En vinternat» (8 s) 2. Dramatisk diktning Tre drama. Ludvig Holberg: Jeppe paa Bjerget (1722) . Henrik Ibsen: Gengangere (1881) . Jon Fosse: Nokon kjem til å komme (1992) 1 3. Lyrisk diktning Ca. 20 dikt. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson: «Salme II» . Erling Christie: «Jailhouse Rock» . Petter Dass: «En Begiæring til Mad. Dorethe Engebrets-Daatter» . Dorothe Engelbretsdatter: «Til Hr. Peter Dass» . Inger Hagerup: «Aust-Vågøy» . Olav H. Hauge: «Til eit Astrup-bilete» og «Kvardag» . Gunvor Hofmo: «Fra en annen virkelighet» . Rolf Jacobsen: «Landskap med gravemaskiner» . *Ruth Lillegraven: «Moby og eg flyttar frå A til C» .