Duncan the Transformation of Australian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Round 8 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 8

The FRONT ROW ROUND 82021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 8 Stand by your Mann Newcastle's five-eighth on his side's STATS season defining run of games ahead Two into one? Why the mooted two-conference NOT system for the NRL is a bad call. GOOD WE ANALYSE EXACTLY HOW THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS INFLUENCED THE GAME INSIDE: NRL Round 8 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 7 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 8 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 8 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Last week, long-serving former player and referee Henry Feature What's (with) the point(s)? 4-5 Perenara was forced into medical retirement from on-field Feature Kurt Mann 6-7 duties. While former player-turned-official will remain as part of the NRL Bunker operations, a heart condition means he'll be Opinion Why the conference idea is bad 8-9 doing so without a whistle or flag. All of us at LeagueUnlimited. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 10 com wish Henry all the best - see Pg 33 for more from the PRLMO. GAME DAY · NRL Round 8 11-27 Meanwhile - the game rolls on. We no longer have a winless team LU Team Tips 11 with Canterbury getting up over Cronulla on Saturday, while THU Canberra v South Sydney 12-13 Penrith remain the high-flyers, unbeaten through seven rounds. -

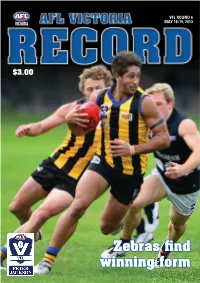

VFL Record Rnd 6.Indd

VFL ROUND 6 MAY 18-19, 2013 $3.00 ZZebrasebras fi nndd wwinninginning fformorm WWAFLAFL 117.16.1187.16.118 d VVFLFL 115.11.1015.11.101 Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL State football CONGRATULATIONS to the West Australian Football League for its victory against the Peter Jackson VFL last Saturday at Northam. The host State emerged from a typically hard fought State player, as well as to Wayde match with a 17-point win after grabbing the lead midway Twomey, who won the WAFL’s through the last quarter. Simpson Medal. Full credit to both teams for the manner in which they What was particularly pleasing played; the game showcased the high standard and quality was the opportunity afforded to so many players to play football that exists in the respective State Leagues. State representative football for the fi rst time. There were One would suspect that a number of players from the game just four players returning to the Peter Jackson VFL team will come under the scrutiny of AFL recruiters come the end that defeated Tasmania last year. of the year. Last year’s Peter Jackson VFL team contained And, the average age of the Peter Jackson VFL team of 24 six players who are now on an AFL list. -

Richmond F.C. Comes to Life

R ic hmond F.c. “The TigeRs” a proud history of a great club as told by those who made it happen R ic hmond F.c. “The TigeRs” a proud history of a great club as told by those who made it happen updated and revised edition interviews by Rhett Bartlett historical essays by trevor ruddell Tigers of the 1960s learn their new club song. Clockwise from top left: Neville Crowe, Kevin Smith, Mike Perry, John Ronaldson, Dick Clay, Owen Madigan. visit slatterymedia.com 2 The Slattery Media Group Eat ’em alive, Tigers 1 Albert Street, Richmond Victoria, Australia, 3121 visit slatterymedia.com Richmond had won its first premiership and we were celebrating. There he stood, a crayfish in each hand, ruckman Barney Herbert, Copyright © Slattery Media Group, 2012 First published by GSP Books, 2007 rampant, on the pedestal of Richmond Mayor G.G.Bennett’s statue Second edition 2012 with a background relief of the Richmond Town Hall. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Barney was yelling: ‘What did we do to them?!’ The AFL logo and competing team logos, emblems and names on this product are all trade marks of and used under ‘Eat em Alive!!’ roared the mob, and Barney waved license from the owner, the Australian Football League, by whom all copyright and other rights of reproduction are reserved. Australian Football League, AFL House, 140 Harbour Esplanade, Docklands, Victoria, 3008 the crays again and again. -

3 Russell Hanson Version 5

Tasmanian Legislative Council Select Committee Inquiry into AFL in Tasmania Submission from Russell Hanson 18 th June 2019 Because of the history of Tasmanian football, in particular, from the creation of the AFL in 1990, there needs to be an understanding of just what has happened since then; what the AFL has done, or more correctly have not done. My submission therefore will examine the history and recent events with an aim to provide context for the Select Committee. It will also look at current problems and solutions and will examine the future with budgets, economic returns and the way forward. This may not follow precisely the Terms of Reference, but it will incorporate the 7 items throughout. I sincerely hope this will work for you as I believe a better understanding of the issues will become apparent. INDEX Opening statement and Index Page1 Executive Summary Page 2 Introduction Pages 3 – 6 History of football including Tasmania Pages 7 – 10 When did football change and what were the ramifications? Page 11 The purposes/values of big banks and the AFL Pages 12 – 14 Participation Rates Pages 15 – 16 Pathways Pages 17 – 18 Where should the Tasmanian team play and be based? Pages 19 – 20 Why Tasmanian youth are denied Page 21 The history of cricket and football in Tasmania Pages 22 – 23 Anniversaries; the Good, the Bad and the Ugly Page 24 AFL Premiership Cup Page 25 How it feels for a current Tasmanian AFL player Page 26 A sample of statements over time Pages 27 – 28 What the journalists say Pages 28 - 30 Tax exemption Pages 31 – -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

Coaching Lessons

VOLUME 23, No 1 May 2009 How AFL Coaches Learn Jeff Gieschen’s Coaching Lessons Celebrating Culture Getting the best out of Indigenous players COACHING EDGE CoachingEdge CONTENTS Jeff Gieschen: coaching 0 5 lessons I have learned Coaching your 10 own child Nutrition for 12 football How AFL 1 4 coaches learn Coaching Indigenous 19 players 28 The key to tackling best in the business: Geelong coach Mark Thompson has transformed the Cats into one of the most dominant sides of the modern era; after round six this year they had won 45 of their past 48 matches. INtrODUCtION A resource for coaches at all levels Welcome to Coaching Edge. the Australian Football Coaches conducted junior development As part of the changes to Association (AFCA) Vic Branch in programs until the VFL assumed CoachingEdge CrEdITS the Australian Football Coaches 1987. There was also a predecessor, responsibility for state development Publisher Association (AFCA) structure in Australian Football Coach, published in 1988), was the editor and Australian Football 2008, in which membership is now by SANFL from 1972 until 1975. designer of the magazine throughout League automatically a part of the process of The inaugural AFCA Vic branch its life. GPO Box 1449 Melbourne Vic 3001 AFL coach accreditation, the president was Allan Jeans, who Coaching Edge is edited by Ken Correspondence to: AFL is now providing services provided the initial editorials. Davis. Ken has a long history of Peter romaniw nationally to complement those Allan was supported by an involvement in sport, physical Peter.romaniw provided by state and regional active committee, including VFL education and coaching. -

Issue 16 AUGUST 17Th 2011

HONI SOIT Issue 16 AUGUST 17th 2011 12-10pm The revue madness continues with THE ARTS REVUE OR HOW WE LEARNT TO LOVE AGAIN and, from the law faculty, THE SOCIALLY AWKWARD NETWORK opening tonight. Head to the Seymour Centre for two great shows! Arts is on til Fri, Law til Sat. Get in quick! $12-23. 7.30PM If you want to get your comedy fix off campus, WED then get down to the Comedy Store at Moore Park for a very special show, STAND UP FOR THE HOPE OF CAMBODIAN CHILDREN. Featuring P52’s own Michael Hing, as well as a host of local talent, the show will raise $$ for children in need. $25 17th 3-5PM And joining the party, THE ED REVUE, GLADIATAR.. $12- 18, also at the Seymour. Go! Enjoy! These people will one day be responsible for our kids! 7PM-9AM One of Humanitarian Week’s highlights is the annual YOUNG VINNIES SLEEP OUT. Camp out on Gadigal Green tonight and experience what homelessness can feel like. With inspiring speakers and talented musicians on hand to educate and entertain, PICK OF it’s sure to be a fulfilling night. Make some likeminded friends! THE WEEK Register at the ACCESS Desk. $5/15, dinner and b/fast provided. • 5pm-8pm After a week of enlightenment, share the love at the Humanitarian Week WRAP UP PARTY. Bevvies, pizza, • hypnotic interactive lightshows from Punk Monk Propaganda. HUG EVERYONE is our only request. FREE. 8pm Those ironic enough to fork out over 100 nuggets for a ticket to WINTERBEATZ should don their gold Diva hoops and hi- tops to break it down with 50 Cent and G Unit, Mario, Lil Kim and FRI Fabolous at Sydney Ent Cent. -

VFL Record Rnd 4.Indd

VFL ROUND 4 APRIL 26-28, 2013 $3.00 WWilliamstownilliamstown wwinsins wwesternestern dderby...erby... aagaingain SSandringhamandringham 116.12.1086.12.108 ddww PPortort MMelbourneelbourne 116.12.1086.12.108 (Photos: Dave Savell) WWilliamstownilliamstown 119.15.1299.15.129 d WWerribeeerribee TTigersigers 55.16.46.16.46 Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL Drug education and awareness the focus AS news of the recent ACC Report and ASADA follow up continues to prevail throughout the media, it’s timely to highlight AFL Victoria’s position. First and foremost illicit and performance-enhancing that our education strategies are substances will not be tolerated in our game. Breaches appropriate. of the AFL’s Anti-Doping Code rightly results in heavy ASADA doesn’t detail its testing regime, for the integrity of sanctions. its testing program, and nor does AFL Victoria ever expect to Education and awareness are two unwavering tenets that know the intricate operation details of the testing program. must prevail in understanding the game’s Anti-Doping policy. Every registered player, including those within community AFL Victoria works with all VFL Clubs to help educate level in country and metropolitan Leagues, can be tested by players and offi cials regarding the requirements of the ASADA. -

At 10-Year Get-Together Berro Recalls His Goals

BRONCOS OLD BOYS LUNCHEON 2016 At 10-year get-together Berro recalls his goals 1 ALTHOUGH ONLY SEVEN members of the 2006 NRL grand final winning team 2 could attend, the annual Broncos Old Boys luncheon to celebrate the milestone was widely acclaimed as one of the best. Almost 300 former players (BOBs) and members of the wider Broncos family attended the luncheon at the Broncos Leagues Club during the June bye weekend. And Justin Hodges, David Stagg, Shane Perry, Shaun Berrigan, Petero Civoniceva, Ben Hannant and Casey McGuire were the 3 premiership winners from a decade ago who were able share to the unforgettable 4 moment with their fellow guests. But for Berrigan, who joined the club from school and made 186 NRL appearances for the club, winning on grand final day had been a long-held aspiration. “As a kid still in school, I recall sitting in Cyril Connell’s office upstairs here and writing down my goals,” he revealed to an attentive audience. “One was to win a grand final and the other was to win the Clive Churchill Medal as best on ground. Luckily that day I was able to do both.” Berrigan, who was also a member of the 5 2000 premiership team, was joined on stage by teammates Petero Civoniceva, Justin Hodges and Ben Hannant and interviewed by MC Ben Ikin, also a Broncos premiership winner form 2000. Another dual premiership winner, Lote Tuqiri, was another special guest interviewed. 6 A number of guests travelled long distance to attend the function, but none 1. -

The Media's Impact on Play in the Australian Football League

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT. STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.2478/pcssr-2018-0001 Managed Play: The Media’s Impact on Play in the Australian Football League Authors’ contribution: Samuel Keith Duncan A) conception and design of the study B) acquisition of data Holmesglen Institute, Australia, Victoria C) analysis and interpretation of data D) manuscript preparation E) obtaining funding ABSTRACT No industry has influenced the transformation of the Australian Football League (AFL) into a professional, commercial business more than the media. Today, the AFL players are paid more than ever and are used as marketing tools to promote and sell the game, often to new fans in new markets of Australia – namely New South Wales and Queensland - who haven’t traditionally played Australian Football, preferring the rugby codes instead. But perhaps the biggest change in the AFL is that the play element is now used as function of business. Put simply, winning leads to more money. As such, the play element is now manipulated more than ever. The game has more coaches implementing more tactics, strategies, game plans and set plays than ever before. These changes can be linked back to the media’s influence on the game. This paper utilises the combined observations and theories of Johan Huizinga and Pierre Bourdieu to create a theoretical lens through which we can understand the media’s growing influence in sport and its impact on play’s transformation. The theory will then be expounded through an extensive analysis of the media’s influence in the AFL, particularly its play element. This analysis will be supported with insights and views from AFL fans, members, commentators and theorists. -

BRAIN STORM the Concussion Class Action That Could Punch a Hole in Aussie Rules Football

WHEN GRANDPA PREYS plus OUR BEACH LIFE MARCH 16, 2019 BRAIN STORM The concussion class action that could punch a hole in Aussie rules football BY Konrad Marshall Melbourne’s Shaun Smith, one of the ex- players threatening to sue, hits the ground after attempting a mark in 1998. HEADCASE Several former Aussie Rules stars are threatening to sue the AFL for memory loss and other cognitive issues they say stem from on-field concussion. But the science in this most emotive of areas is anything but clear. BY Konrad Marshall NDER LIGHTS in a drifting rain, a flaccid Association, and until recently was the dial-a-quote The case is well timed. Concussion is big news. The windsock flops about as 44 footballers slip, chairman of A-League soccer team Adelaide United. finer details of a class action brought against the National slide, trip and collide on an oval east of Now, though, Griffin is angling to become a thorn in the Football League (NFL) in the United States were settled Adelaide. It’s a Friday night game in the side of the Australian Football League, this time repre- in 2017 with a fund to compensate thousands of damaged USouth Australian National Football League (SANFL), senting ex-players – including a premiership ruckman, a gridiron players; it has already handed out more than and commercial lawyer Greg Griffin is among a crowd Brownlow Medal-winning rover, and the man who once $US629 million ($895 million). As more claims are of a few thousand swilling Coopers Ale and scarfing plucked what is commonly called “The Mark of the lodged, the estimated payout could balloon to as much Vili’s Pies. -

Sydney Football League • Sydney Football Association

SYDNEY FOOTBALL LEAGUE • SYDNEY FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION SYDNEY FOOTBALL LEAGUE SYDNEY FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION Balmain • Baulkham Hills Bankstown • Blacktown Campbelltown • East Sydney Camden • Hawkesbury Holroyd-Parramatta Liverpool Anzacs • Wollongong North Shore • Pennant Hills Macquarie University St. George • Sydney University Manly Warringah • Penrith Western Suburbs Penshurst • Sutherland University of NSW SYDNEY FOOTBALL LEAGUE Saturday-Sunday August 6-7, 1994 1994 FIXTURES & RESULTS No. 18 $1.00 ROUND ONE • Saturday April 9 ROUND 10 ·Sunday June 19 Holroyd Parramatta 23.27-165 v Balmain 9.7-61 104p1s Balmain 12.18-90 v Hol Parramatta 22.29·161 71pts Campbelltown 12.16-88 v East Sydney 13.5-83 5p1s Western Subs 17.15-117vStGeorge 16.8-104 13pts North Shore 19.13·127 v Pennant Hills 10.16-76 51pts Baulkham Hills 17.14·116 v Sydney Uni 8.16·64 52pts St George 24.12·156 v Western Suburbs 12.13·85 71pts East Sydney 12.14·86 v Campbelltown12.19·91 5pts Sunday April 10 Pennant Hills 16.20.116 v North Shore 10.9-69 47pts Sydney Uni 21.17-143 v BaulkhamHills 10.21·81 62p1s MAGPIES SKIN THE BEARS ROUND 11 • Saturday June 25 ROUND TWO • Sal April 16 Sydney Uni 4.18·42 v East Sydney 17.17-119 77pts East Sydney17.19-121 vSydney Uni 10.14-74 47p1s Sunday June 26 Sunday April 17 Ho~Parramatta 8.15-63 v Western Subs 13.19·97 34pts Western Subs 20.16-136 v Ho~Parraniatta 14.15-99 37pts SI George 23.20.158 v Baulkham Hills 6.10-46 112pts Uni Give the Saints a Fright Baulkham Hills 12.15-87 v St George 23.22·160 73pts Campbelllown 21.16-142 v Pennant Hills 13.7-85 57pts Pennant Hills 13.9-87 v Campbelltown 24.22·166 79pts North Shore 32.20.222 v Balmain 7.8·50 172pts The final four appears set as We stem Suburbs with a 12-point win in the 16th Balmain 14.17-101 vNorthShore21.19-145 44pts ROUND 12 ·Saturday July 2 round challenge at Gore Hill last Sunday have all but ended the chances of North Baulkham Hills 14.13-97 v Hol•P'malta 24.15-159 62p1s ROUND THREE • Sal April 23 East Sydney 16.19-115 vStGeorge 5.7-37 78p1s Shore participating in their seventh successive finals series.