Summer 06 Vol 6 Ed 15 Aug 06.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Chalmers Archer, Jr

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Chalmers Archer, Jr. PERSON Archer, Chalmers, 1928- Alternative Names: Chalmers Archer, Jr.; Life Dates: April 21, 1928-February 24, 2014 Place of Birth: Tchula, Mississippi, USA Residence: Manassas, VA Occupations: Soldier; Psychology Professor Biographical Note Combat medical technician, author and education administrator Chalmers Archer, Jr. was born on April 21, 1928 in Tchula, Mississippi to Eva R. Archer, a teacher and Chalmers Archer, Sr., a farmer. As a child, his father and uncles rented a hilltop of more than four hundred acres known as the “Place”, where they farmed, cultivated orchards, raised livestock and built smokehouses. The land was sold when Archer was twelve years old and his family moved to Lexington, Mississippi. After graduating from Ambrose High School, he attended Tuskegee University for one year Mississippi. After graduating from Ambrose High School, he attended Tuskegee University for one year before volunteering for the United States Army Air Corps. Archer was in the United States Army Air Corps for one year and then transferred to the Army. He served on a medical crew as a master sergeant technician during the Korean War, where his unit’s job was to retrieve wounded soldiers. In 1952, Archer began training at Fort Bragg’s Psychological Warfare Center as part of the newly formed United States Army’s Special Forces. His unit was one of the first to enter Vietnam where he trained original Special Forces teams of the South Vietnamese army. On October 21, 1957, Archer’s unit was ambushed and he witnessed the first American combat deaths in Vietnam, as well saving the lives of American and Vietnamese soldiers. -

Arctic Rail & Road

Bodø Cruise Port 7 - Arctic Rail & Road Magnificent Nature and History Photo: NSB FACTS: Description Combination of train and coach from Rognan. Your return journey will be by Duration: 6 hours 45 min Bodø to Rognan in the Municipality of coach over the mountains to Misvær and Capacity: Min. 25 pax, Max. 80 Saltdal. Enjoy a scenic train ride on a then on to the famous Saltstraumen, pax (40 by train and commuter train along the beautiful before returning to your ship in Bodø. 40 by coach in Skjerstad fjord between Bodø and reverse order) Highlights on the excursion Blood Road Museum where we offer home-made and other Blood Road Museum tells the story of the produce based on natural ingredients. lives and work of prisoners of war under In summer you can enjoy the scent and the German regime from 1942-1945 and taste of the many fascinating herbs in the NOTES: is presented in German barracks moved garden, or just sit down and take in the here from Dunderdalen. Thousands of pri- tranquillity of Tofte. This tour operates in reverse order soners of war from eastern Europe were when the group size exceeds 40 sent north to build roads and railways. Saltdal Folk Museum pax. Departure time for the second Travel back in time, to 1880, where the group is 12:10 by train. The tour The Herb Garden at Tofte farmwife, Berit, welcomes you to a beauti- may be extended with city sightse- The Herb Garden in Tofte is located in a ful farmstead. Berit will take you inside the eing if time. -

Okstindan Glacier

RABOTHYTTA CABIN on the edge of the Okstindan glacier WELCOME TO HEMNES Skaperglede mellom smul sjø og evig snø Mo i Rana 40 km Sandnessjøen 70 km HEMNES Mosjøen 50 km – a creative community in the heart of Helgeland Hemnes - a great place to live! Fascinating facts The Municipality of Hemnes has a lush countryside, idyllic valleys and five The Municipality of Hemnes is situated in the - Hemnes’ coat of arms shows a golden boat- . villages: Bleikvasslia, Korgen, Bjerka, Finneidfjord and Hemnesberget. The heart of Helgeland. Our district enjoys excellent builder’s clamp on a blue background, symbolising total population is about 4 500. In addition to friendly services and a thri- communications as well as scenic surroundings the area’s ancient traditions. Since we started ving community of artists and musicians, Hemnes offers boat production, – and we have plenty of room should you wish counting in 1850, close to 300 000 boats have window and furniture factories, agriculture and significant hydropower pro- to settle here, with your family or your business! been built in Hemnes! duction. Our cultural calendar includes popular summer festivals and an - Leif Eirikson, a replica of the ship sailed by the outdoor historical play. In Hemnes you will also find Northern Norway’s Many residents commute to jobs in Mosjøen, Viking explorer to the New World, is displayed in tallest mountain, the eighth largest glacier on the Norwegian mainland, Sandnessjøen and Mo i Rana. Hemnes has rail- its own park in Duluth, Minnesota. Crafted by the way connections, highway E6 passes through sheltered fjords, wonderful fishing opportunities, and a wilderness that will skilled boat-builders on a farm in Leirskarddalen, our district, and the new 10.6 km Toven Tunnel the replica ship sailed across the Atlantic in 1926. -

2017 Fourth Quarter Music Preview

2017 INHere’s a line on what’s fallingTHE into place Q for label and promotion teams in the FOURTH QUARTER fourth quarter. MUSIC PREVIEW ARISTA ible momentum propelled by the successes of new soon. Urban’s Ripcord has already notched fi ve chart LanCo are telling the “Greatest Love Story” as that artists Midland and Carly Pearce.” Midland’s debut toppers. The label hopes Jon Pardi’s top 10 “Heart- single climbs the charts, as well as “You Broke Up album On The Rocks is out Sept. 22 and features the ache On The Dance Floor” will become his third No. With Me” from Walker Hayes, and Brad Paisley’s “Last gold single “Drinkin’ Problem” and their latest release 1 from his gold album California Sunrise. Pardi’s been Time For Everything.” “Tim McGraw and Faith Hill “Make A Little.” Lamb reports Pearce’s debut single on the road all year with Dierks Bentley, Bryan and return to the charts with their powerful single ‘Rest “Every Little Thing” continues to climb inside the top also headlining his own tour. Other ascending singles Of Our Life,’” says VP/Promotion Josh Easler. Expect 10, “a breakthrough for a solo female artist – and only include Bentley’s “What The Hell Did I Say” from his a new album from McGraw and Hill in November. one of four active on the chart.” Pearce’s debut album gold album Black. Bentley’s prepping for studio time “Also coming this fall will be new music from Cam is out Oct. 13. “Big Machine Records is also home in early 2018. -

Kesha Releases "Best Music of Her Career" with 'Rainbow,' out Today

Kesha Releases "Best Music of Her Career" with 'Rainbow,' Out Today Singer Paints the World With Video, Essay for 'Rainbow' Title Track 'Rainbow' was worth the wait. That's the consensus about Kesha's first album since 2012, out today on Kemosabe Records/RCA Records. In a four-star review, Rolling Stone calls 'Rainbow' "the best music of her career," while Entertainment Weekly gives the album an A- and proclaims it "an artistic triumph." Order and download links below. Billboard describes lead single "Praying" as a "ballad that tears at your soul" while Consequence of Sound says "no other song in recent memory so perfectly embodies the way in which hope itself is a kind of triumph." Other reviewers have highlighted songs including "Hymn," a "powerful outsider anthem" (Rolling Stone); the "feminist battle cry" (Mic) of "Woman"; "Hunt You Down," which PopCrush describes as "far more authentic than anything currently playing on country radio"; and "Learn to Let Go," "the most carefree, uplifting song we've heard from her" (Jezebel). Additional Praise for 'Rainbow': New York Times: "On 'Rainbow,' Kesha nods to the past and roars into the future." USA Today: "Songs that see Kesha at her defiant, unbridled best." Billboard: "Kesha has the swagger for neo-glam, the grit for old-school soul, the pipes for power- balladry." Stereogum: "Kesha's grand return is a smashing success." Watch Kesha perform "Praying" on Good Morning America HERE. Check out Kesha on The Tonight Show HERE. Kesha also unveils an in-the-studio video for the title track today and writes about "the song that started a new chapter in my life" in an essay for Refinery 29. -

Fall 04-1.Qxd

Volume 4, Edition 4 Fall 2004 A Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical Professionals Dedicated to the Indomitable Spirit & Sacrifices of the SOF Medic “That others may live.” Pararescuemen jump from a C-130 for a High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) free fall drop from 12,999 feet at an undisclosed location, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Official Photo by: SSgt Jeremy Lock. From the Editor The Journal of Special Operations Medicine is an authorized official quarterly publication of the United States Special Operations Command, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. It is not a product of the Special Operations Medical Association (SOMA). Our mission is to promote the professional development of Special Operations medical personnel by providing a forum for the exam- ination of the latest advancements in medicine. Disclosure: The views contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official Department of Defense posi- tion. The United States Special Operations Command and the Journal of Special Operations Medicine do not hold themselves respon- sible for statements or products discussed in the articles. Unless so stated, material in the JSOM does not reflect the endorsement, official attitude, or position of the USSOCOM-SG or of the Editorial Board. Articles, photos, artwork, and letters are invited, as are comments and criticism, and should be addressed to Editor, Journal of Special Operations Medicine, USSOCOM, SOC-SG, 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, FL 33621-5323. Telephone: DSN 299- 5442, commercial: (813) 828-5442, fax: -2568; e-mail [email protected]. All scientific articles are peer-reviewed prior to publication. -

A Vibrant City on the Edge of Nature 2019/2020 Welcome to Bodø & Salten

BODØ & SALTEN A vibrant city on the edge of nature 2019/2020 Welcome to Bodø & Salten. Only 90 minutes by plane from Oslo, between the archipelago and south, to the Realm of Knut Hamsun in the north. From Norway’s the peaks of Børvasstidene, the coastal town of Bodø is a natural second biggest glacier in Meløy, your journey will take you north communications hub and the perfect base from which to explore via unique overnight accommodations, innumerable hiking trails the region. The town also has gourmet restaurants, a water and mountain peaks, caves, fantastic fishing spots, museums park, cafés and shopping centres, as well as numerous festivals, and cultural events, and urban life in one of the country’s including the Nordland Music Festival, with concerts in a beautiful quickest growing cities, Bodø. In the Realm of Hamsun in the outdoor setting. Hamsun Centre, you can learn all about Nobel Prize winner Knut Hamsun`s life and works, and on Tranøy, you can enjoy open-air This is a region where you can get close to natural phenomena. art installations against the panoramic backdrop of the Lofoten There is considerable contrast – from the sea to tall mountains, mountain range. from the midnight sun to the northern lights, from white sandy beaches to naked rock. The area is a scenic eldorado with wild On the following pages, we will present Bodø and surroundings countryside and a range of famous national parks. Here, you can as a destination like no other, and we are more than happy immerse yourself in magnificent natural surroundings without to discuss any questions, such as possible guest events and having to stand in line. -

View Our 2021 Brochure

SCANDINAVIA 2021 TRAVEL BROCHURE WHY TRAVEL WITH BREKKE TOURS Let our clients tell you why... This was a trip of a lifetime for us. The Brekke staff was so helpful planning our pre- and post- trips. Our guide was fantastic! H.L. & P. Z. ~ Hager City, WI Fantastic adventure! The tour provided us with a great overview of Norway, its history, culture, and spirit. We enjoyed the tour and all of the folks we met along the way. R. & B.K. ~ Sturgis, SD This was the trip of a lifetime for my 89 year old father, my sister, brother, and I. We learned so much about the beautiful country of our ancestors, its culture, as well as the kindness and humor of the native Norwegians. We had a small tour and we all became like one big family. I can’t wait to go back to Norway with Brekke Tours! BREKKE TOURS J.B. ~ Newton, IA I have lived in Norway and still saw many new YOUR SCANDINAVIAN SPECIALIST SINCE 1956 places and learned so much of my family’s country from our exceptional guide. I am most impressed with my experience and would not 2020 was certainly a year for the record books! We would like to thank all of our hesitate to take another trip with Brekke. clients for their patience, understanding, and words of encouragement throughout R.H. ~ Bakersfield, CA the year as we struggled with the ever-changing policies and restrictions on Second tour with Brekke and completely overseas travel. Although we were greatly disappointed in having to reschedule satisfied with both pre-planning and escorted all of our tours in 2020, we are hoping 2021 brings a ray of hope to the travel portions of both trips. -

AITO Inspiration – Learning Holidays

AITO Inspiration – Learning holidays 27 February 2018 Pick up a new hobby or learn a new skill with these holiday ideas from travel specialist members of The Association of Independent Tour Operators (www.aito.com). From papermaking in Japan to a family archaeological adventure in Greece, and from a culinary course in Italy to a painting retreat in Kerala, here are some of the best learning holidays on offer in 2018: History, culture, and family adventures in beautiful Peru – from £3,295 pp with Activities Abroad With a remarkable history and plenty of natural wonders to uncover, every member of the family will be fascinated by Peru. Discover the animals and plants of the Amazon rainforest on an ethnobotanical tour: explore the Sacred Valley of the Incas by foot and zip line, mountain bike between ancient archaeological sites, unearth Machu Picchu’s wonders on a private tour, explore Cusco and learn how to make chocolate, raft along the Chuquicahuana River and kayak on Lake Titicaca. Departing 21 July, Incan Adventure in Peru costs from £3,295 pp for adults and £2,795 pp for children (eight-10 years), and includes internal flights, vistadome train, transfers, 11 nights’ B&B accommodation, six lunches, seven dinners, activities listed, all equipment and expert guides. International flights extra. Call Activities Abroad on 01670 789 991 (www.activitiesabroad.com). Enjoy a brush with Kerala on a painting retreat – from £3,395 pp with Authentic Adventures Under the watchful eye of a well-established painting tutor, capture the essence of Kerala on this 15- day adventure. -

Kesha Unveils "Rainbow Tour," Her First Solo Trek Since 2013

August 1, 2017 Kesha Unveils "Rainbow Tour," Her First Solo Trek Since 2013 General On Sale Starts Saturday, August 5 at keshaofficial.com LOS ANGELES, Aug. 1, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Kesha launches her "Rainbow Tour," a six- week trek across North America, on September 26th in Birmingham, AL at Iron City. The singer's first solo tour since 2013's "Warrior Tour," the "Rainbow Tour" takes Kesha to 21 markets, wrapping November 1st at the Hollywood Palladium. Kesha will perform new songs from her highly anticipated album 'Rainbow' (out August 11 from Kemosabe Records/RCA Records) for the first time on tour, as well as her previous global hits. Additionally, every pair of tickets to the "Rainbow Tour" comes with a physical copy of Kesha's new album. VIP ticket packages for the "Rainbow Tour" will be available and include exclusive signed merchandise and show benefits. "My new album 'Rainbow' is dedicated to my fans. And I'm so excited to be able to invite you all to come boogie with me on my new 'Rainbow Tour'," says Kesha. "I would not have made it to this point without my animals and supporters so now come out and join the celebration with me." Rolling Stone, Billboard, and The LA Times hail the songs from Kesha's first album in five years as a triumphant return. Slate lauds "Praying" as "a testament to the strength she says she wants to inspire in others." Kesha has released two other advance tracks from 'Rainbow': "Woman" and "Learn To Let Go." Fans will get an additional look into the music of 'Rainbow' with an intimate private live performance by Kesha taking place at YouTube Space LA, streaming on Wednesday, August 2nd via YouTube.com. -

Kesha Offers up a 'Hymn' for the Hymnless

Kesha Offers Up a 'Hymn' For the Hymnless August 3rd — Anticipation continues to build for Kesha's new album 'Rainbow' with the release of "Hymn," a song dedicated to dreamers and outsiders everywhere. Following "Praying," "Woman" and "Learn to Let Go," "Hymn" is the fourth advance track from 'Rainbow,' out August 11th on Kemosabe Records/RCA Records. Pre-order and download links below. Listen to "Hymn" here: http://smarturl.it/pvHymn Kesha intends for "Hymn" to connect with the fans, many of whom have reached out to share personal stories of how her music had encouraged and helped them navigate through difficult times in their lives. "This is a hymn for the hymnless, kids with no religion," Kesha sings over the sparkling, otherworldly production of Ricky Reed and Jonny Price. Kesha wrote on the song with her producers, Cara Salimando and her mother, Pebe Sebert. "This song is dedicated to all the idealistic people around the world who refuse to turn their backs on progress, love, and equality whenever they are challenged," Kesha writes in an essay about "Hymn" that appears in Mic. "It's dedicated to the people who went out into the streets all over the world to protest against racism, hate, and division of any kind. It's also dedicated to anyone who feels like they are not understood by the world or respected for exactly who they are." Read the full essay here via Mic: http://smarturl.it/KMIC Earlier this week, Kesha announced the six-week North American "Rainbow Tour," her first solo tour since 2013's "Warrior Tour." Dates here: http://smarturl.it/RainbowTour -

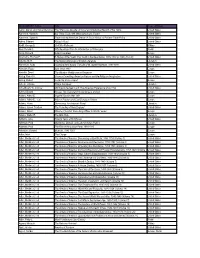

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert Bendiner The Strenuous Decade: A Social and Intellectual Record of the 1930s United States Aaronson, Susan A. Are There Trade-Offs When Americans Trade? United States Aaronson, Susan A. Trade and the American Dream: A Social History of Postwar Trade Policy United States Abbey, Edward Abbey's Road United States Abdill, George B. Civil War Railroads Military Abel, Donald C. Fifty Readings Plus: An Introduction to Philosophy World Abels, Richard Alfred The Great Europe Abernethy, Thomas P. A History of the South: The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819 (p.1996) (Vol. IV) United States Abrams, M. H. The Norton Anthology of English Literature Literature Abramson, Rudy Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 United States Absalom, Roger Italy Since 1800 Europe Abulafia, David The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms Europe Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination United States Abzug, Robert Inside the Vicious Heart Europe Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Literature Achenbaum, W. Andrew Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience since 1790 United States Acton, Edward Russia: The Tsarist and Soviet Legacy, 2nd ed. Europe Adams, Arthur E. Imperial Russia After 1861 Europe Adams, Arthur E., et al. Atlas of Russian and East European History Europe Adams, Henry Democracy: An American Novel Literature Adams, James Trustlow The Founding of New England United States Adams, Simon Winston Churchill: From Army Officer to World Leader Europe Adams, Walter R. The Blue Hole Literature Addams, Jane Twenty Years at Hull-House United States Adelman, Paul Gladstone, Disraeli, and Later Victorian Politics Europe Adelman, Paul The Rise of the Labour Party, 1880-1945 Europe Adenauer, Konrad Memoirs, 1945-1953 Europe Adkin, Mark The Charge Europe Adler, Mortimer J.