A Brief History of All Saints' Church, Brantingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humberside Police Area

ELECTION OF A POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER for the HUMBERSIDE POLICE AREA - EAST YORKSHIRE VOTING AREA 15 NOVEMBER 2012 The situation of each polling station and the description of voters entitled to vote there, is shown below. POLLING STATIONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO r VOTE r VOTE r VOTE 1 21 Main Street (AA) 2 Kilnwick Village Hall (AB) 3 Bishop Burton Village Hall (AC) Main Street 1 - 116 School Lane 1 - 186 Cold Harbour View 1 - 564 Beswick Kilnwick Bishop Burton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 4 Cherry Burton Village (AD) 5 Dalton Holme Village (AE) 6 Etton Village Hall (AF) Hall 1 - 1154 Hall 1 - 154 37 Main Street 1 - 231 Main Street West End Etton Cherry Burton South Dalton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 7 Leconfield Village Hall (AG) 8 Leven Recreation Hall (AH) 9 Lockington Village Hall (AI) Miles Lane 1 - 1548 East Street 1 - 1993 Chapel Street 1 - 451 Leconfield LEVEN LOCKINGTON EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE 10 Lund Village Hall (AJ) 11 Middleton-On-The- (AK) 12 North Newbald Village Hall (AL) 15 North Road 1 - 261 Wolds Reading Room 1 - 686 Westgate 1 - 870 LUND 7 Front Street NORTH NEWBALD MIDDLETON-ON-THE- WOLDS 13 2 Park Farm Cottages (AM) 14 Tickton Village Hall (AN) 15 Walkington Village Hall (AO) Main Road 1 - 96 Main Street 1 - 1324 21 East End 1 - 955 ROUTH TICKTON WALKINGTON 16 Walkington Village Hall (AO) 17 Bempton Village Hall (BA) 18 Boynton Village Hall (BB) 21 East End 956 - 2 St. -

U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Barnards Family of South Cave U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave Historical background: The papers relate to the branch of the family headed by Leuyns Boldero Barnard who began building up a landed estate centred on South Cave in the mid-eighteenth century. His inherited ancestry can be traced back to William and Elizabeth Barnard in the late sixteenth century. Their son, William Barnard, became mayor of Hull and died in 1614. Of his seven sons, two of them also served time as mayor of Hull, including the sixth son, Henry Barnard (d.1661), through whose direct descendants Leuyns Boldero Barnard was eventually destined to succeed. Henry Barnard, married Frances Spurrier and together had a son and a daughter. His daughter, Frances, married William Thompson MP of Humbleton and his son, Edward Barnard, who lived at North Dalton, was recorder of Hull and Beverley from the early 1660s until 1686 when he died. He and his wife Margaret, who was also from the Thompson family, had at least seven children, the eldest of whom, Edward Barnard (d.1714), had five children some of whom died without issue and some had only female heirs. The second son, William Barnard (d.1718) married Mary Perrot, the daughter of a York alderman, but had no children. The third son, Henry Barnard (will at U DDBA/14/3), married Eleanor Lowther, but he also died, in 1769 at the age of 94, without issue. From the death of Henry Barnard in 1769 the family inheritance moved laterally. -

Barn Cottage, Main Street, Brantingham £450,000 Fabulous Stone and Tiled Construction Village Has a Public House/Restaurant and Has "Karndean' Flooring and Radiator

Barn Cottage, Main Street, Brantingham £450,000 Fabulous stone and tiled construction village has a public house/restaurant and Has "Karndean' flooring and radiator. Leads extended 4 Bedroom Link Detached House communal hall and there are many delightful into: with long landscaped garden located within walks close by including the Wolds Way which SITTING ROOM 17' x 9'9 (5.18m x 2.97m) the heart of this highly regarded village. lies to the west of the village. Local shops, Superb extension with pitched roof and views Viewing highly recommended. schools & sporting facilities can be found at of the rear garden: Has radiator, oak the nearby villages of South Cave, Elloughton INTRODUCTION engineered flooring and french doors leading & Brough, each village being almost Appointed to a high standard, this delightful to a delightful paved patio. equidistant and approximately five minutes property is situated on Main Street within by car. A main line rail station is located at KITCHEN 14'2 x 8'4 (4.32m x 2.54m) view of the village pond. The rear garden Brough with direct links to Hull & London This well fitted kitchen offers a offers fabulous views of the surrounding Kings Cross. comprehensive range of cream high gloss countryside. The accommodation comprises fronted floor and wall units complimented by Entrance Hall with Cloak/WC off, Living Room, ENTRANCE HALL solid wood work surfaces and integrated Dining Room, rear Sitting Room extension With uPVC door and glazed screen, radiator. dishwasher; plumbed for washing machine; with garden views and a spacious modern CLOAKROOM 1.5 bowl sink unit; ceramic tiled floor; radiator. -

Friendly Societies in East Yorkshire

Bands and Banners George Tutill - Banner Maker George Tutill was born in the market town of Howden in the East Riding in 1817. George was the only child of Thomas Tutill, who was a miller, and Elizabeth. By the time George was twenty one he had moved to Hull and in June 1838 he married Emma Fairfield. He was known as an artist and exhibited a number of landscape paintings in London between 1846 and 1858. It was, however, as an entrepreneur of banners and regalia making that Tutill made his reputation and fortune. He moved to premises in City Road, London, and many societies went to Tutill’s for their emblems, regalia and banners, such as Friendly Societies, Trade Unions, Freemasons and Sunday Schools. George Tutill was active in the friendly society ‘The Ancient Order of Foresters’ from the 1840’s. Front cover of the 1895 Tutill catalogue Tutill advertisement George Tutill produced the banners from raw silk that was woven to the required size on a purpose built jacquard loom. The silk was then painted in oils on both front and back. Next, they were highly embellished with golden scrollwork with ornate lettering on streamers, and the central painted image, would be supplemented by inset cameos. The purchase of a banner was an extravagance entered into as soon as a society’s funds and membership allowed. With dimensions of up to 12 feet by 11 feet a Tutill banner could require eight men to carry it; two to carry each of the vertical poles and four more to hold the The studio of George Tutill at City Road, Oddfellows sash and badge made by George Tutill. -

12 Manor Fields, Hull, HU10 7SG Offers Over £500,000

12 Manor Fields, Hull, HU10 7SG • Executive Detached • Exclusive Cul De Sac • Private Garden • Beautiful Kitchen/Diner • Four Bedrooms • En-Suite and Dressing Room • Conservatory • Large Living Space • VIEWING IS A MUST! Offers over £500,000 www.lovelleestateagency.co.uk 01482 643777 12 Manor Fields, Hull, HU10 7SG INTRODUCTION Situated in this exclusive setting, this attractively designed modern four bedroomed detached home borders fields to the rear and forms part of the award winning development of Manor Fields which is situated in the picturesque and highly desirable village of West Ella. Built a number of years ago to a high specification, the development is located off Chapel Lane, West Ella Road and blends in with the village scene typified by rendered white-washed houses and cottages. The accommodation boasts central heating, double glazing and briefly comprises an entrance hall, cloakroom/WC, rear lounge with feature fireplace and double doors leading into the fabulous conservatory, which in turn leads out to the garden, large dining room/sitting room, modern breakfasting kitchen with range of appliances and utility room with access to the integral garaging. At first floor level there is a spacious landing, bathroom and four bedrooms, the master of which includes a fitted dressing room and a luxurious en suite. The property is set behind a brick wall with farm style swing gate providing access to the blockset driveway and onwards to the single garage. The rear garden borders fields and includes a patio area with raised lawned garden beyond. Viewing is essential to appreciate this fine home. LOCATION West Ella is a small village in the parish of Kirk Ella and West Ella, west of Kirk Ella within the East Riding of Yorkshire on the eastern edge of the Yorkshire Wolds. -

Ellerker Enclosure Award - 1766

Ellerker Enclosure Award - 1766 Skinn 1 TO ALL TO WHOM THESE PRESENTS SHALL COME John Cleaver of Castle Howard in the County of York gentleman John Dickinson of Beverley in the said County of York Gentleman and John Outram of Burton Agnes in the said County of York Gentleman Give Greeting WHEREAS by an Act of Parliament in the fifth year of the reign of his Gracious Majesty King George the Third ENTITLED An Act for Dividing and Inclosing certain Open Commons Lands Fields and Grounds in the Township of Ellerker in the Parish of Brantingham in the East Riding of the County of York RECITING that the Township of Ellerker in the Parish of Brantingham in the east Riding of the County of York consists of Seventy Five oxgangs of Land and some odd Lands and also Fifty Two Copyhold and Freehold ancient Common Right Houses and Frontsteads and of certain parcels of Ground belonging to the said Common Right Houses and Frontsteads called Norfolk Acres the Dams the Common Ings Rees Plumpton Parks and the Flothers with several oxgangs of Land and odd lands and pieces or parcels of Ground lying in the open Common Fields and open Common Pastures and Meadow Grounds twelve of which oxgangs Are Freehold and Sixty Three of them are Copyhold of the Bishop of Durham of his Manor of Howden Twenty Four of which Copyhold oxgangs are Hall Lands and are lying in the Hall Fields and in the Hall Ings and the remaining Thirty Four Copyhold oxgangs and the said Twelve Freehold oxgangs and the said odd lands are called Town Lands and are lying in the Town Fields and in -

CITY of HULL AC NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2004 ***Christmas Party

CITY OF HULL AC NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2004 ***Christmas Party*** *Triton Inn, Brantingham, Saturday, 11th December* *5 Course Christmas Menu* *Bar & Disco, Cost £21.50 per Person* *£5.00 Deposit by 20th November 2004* *We have just 68 places only, for what should be a great night,* *so, if you are interested see Carol Ingleston,* *or telephone her on 07766 540563. Book early to avoid disappointment* Training Sessions Monday 5.45pm Humber Bridge top car park Speed session Tuesday 7.00pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Club night Thursday 9.00am Elloughton Dale top Pensioner’s Plod Thursday 6.00pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Club night Thursday 700pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Fartlek Session Saturday 8.30am Wauldby Green, Raywell 3 to 5 mile cross country Sunday 8.45am Brantingham Dale car park half way down Cross country City of Hull 3 Mile Winter League Series - all start at 7.15pm Tue 9th Nov Humber Bridge top car park Tue 14th Dec as above Tue 11th Jan as above Tue 1st Feb as above Tue 1st Mar as above The first race of this series was held on 12th October and attracted 61 runners. This was not a problem at the finish due to there being no handicap times. However, for future races, we could possibly get 61 plus runners all coming through the finish line at the same time. So, could I please ask you to stay in line in the funnel, do not pass the person in front of you and display your number clearly for the markers. If anything does go wrong at the finish with the recording of the times and numbers, please remember, that our finishing crew are all volunteers, who do an excellent job. -

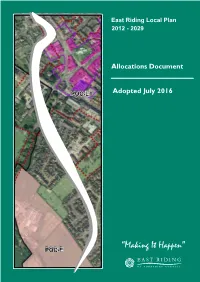

Allocations Document

East Riding Local Plan 2012 - 2029 Allocations Document PPOCOC--L Adopted July 2016 “Making It Happen” PPOC-EOOC-E Contents Foreword i 1 Introduction 2 2 Locating new development 7 Site Allocations 11 3 Aldbrough 12 4 Anlaby Willerby Kirk Ella 16 5 Beeford 26 6 Beverley 30 7 Bilton 44 8 Brandesburton 45 9 Bridlington 48 10 Bubwith 60 11 Cherry Burton 63 12 Cottingham 65 13 Driffield 77 14 Dunswell 89 15 Easington 92 16 Eastrington 93 17 Elloughton-cum-Brough 95 18 Flamborough 100 19 Gilberdyke/ Newport 103 20 Goole 105 21 Goole, Capitol Park Key Employment Site 116 22 Hedon 119 23 Hedon Haven Key Employment Site 120 24 Hessle 126 25 Hessle, Humber Bridgehead Key Employment Site 133 26 Holme on Spalding Moor 135 27 Hornsea 138 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 28 Howden 146 29 Hutton Cranswick 151 30 Keyingham 155 31 Kilham 157 32 Leconfield 161 33 Leven 163 34 Market Weighton 166 35 Melbourne 172 36 Melton Key Employment Site 174 37 Middleton on the Wolds 178 38 Nafferton 181 39 North Cave 184 40 North Ferriby 186 41 Patrington 190 42 Pocklington 193 43 Preston 202 44 Rawcliffe 205 45 Roos 206 46 Skirlaugh 208 47 Snaith 210 48 South Cave 213 49 Stamford Bridge 216 50 Swanland 219 51 Thorngumbald 223 52 Tickton 224 53 Walkington 225 54 Wawne 228 55 Wetwang 230 56 Wilberfoss 233 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 57 Withernsea 236 58 Woodmansey 240 Appendices 242 Appendix A: Planning Policies to be replaced 242 Appendix B: Existing residential commitments and Local Plan requirement by settlement 243 Glossary of Terms 247 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Foreword It is the role of the planning system to help make development happen and respond to both the challenges and opportunities within an area. -

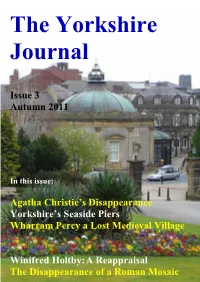

Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Agatha Christie's Disappearance

The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2011 In this issue: Agatha Christie’s Disappearance Yorkshire’s Seaside Piers Wharram Percy a Lost Medieval Village Winifred Holtby: A Reappraisal The Disappearance of a Roman Mosaic Withernsea Pier Entrance Towers Above: All that remain of the Withernsea Pier are the historic entrance towers which were modelled on Conwy Castle. The pier was built in 1877 at a cost £12,000 and was nearly 1,200 feet long. The pier was gradually reduced in length through consecutive impacts by local sea craft, starting with the Saffron in 1880 then the collision by an unnamed ship in 1888. Then following a collision with a Grimsby fishing boat and finally by the ship Henry Parr in 1893. This left the once-grand pier with a mere 50 feet of damaged wood and steel. Town planners decided to remove the final section during sea wall construction in 1903. The Pier Towers have recently been refurbished. In front of the entrance towers is a model of how the pier would have once looked. Left: Steps going down to the sands from the entrance towers. 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Above: Early autumn in the village of Burnsall in the Yorkshire Dales, which is situated on the River Wharfe with a five-arched bridge spanning it Cover: The Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Editorial n this autumn issue we look at some of the things that Yorkshire has lost, have gone missing and disappeared. Over the year the Yorkshire coast from Flamborough Head right down to the Humber estuary I has lost about 30 villages and towns. -

Feb2020 NEIL News.Pub

Rudston RUDSTON COMMUNITY Newsletter Also available, in full colour, on line at :- February www.rudston.org.uk/newsletter 2020 This month’s Newsletter is kindly sponsored by: Hall Bros Fuels & Heating 1 Editor’s Letter Dear Everyone, May I offer a belated Happy and Healthy New Year to all the resi- dents of Rudston. We are having problems with the printer again, so apologies for the fact that this edition will probably be late. Welcome to anyone who has recently come to live in our lovely village. For those who are keen to be involved in village activities, there is a list of people, whom you can contact on the back page. Thank you to all those people who have sent good wishes on my recovery following a broken ankle. It is a long process, but things are improving. They say that misfortunes come in threes; well I can cer- tainly attest to that. When we returned from a wonderful cruise at the end of October, we realised that I had left my IPad in the cabin. I thought that I wouldn’t see it again, but I am informed that it will be re- turned to me in March...it is at present enjoying its own cruise around the Caribbean. Then followed the afore mentioned break and when I returned from hospital, what should I find in the post, but a speeding fine. ..in over 50 years of driving, I have never so much as incurred a parking fine! Hopefully that is the end of my misfortunes for the time being anyway! It was a shame that the Village Hall Party had to be cancelled, but it did seem that lots of people had previous engagements. -

EAST RIDING of YORKSHIRE and KINGSTON UPON HULL Joint Local Access Forum

EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE AND KINGSTON UPON HULL Joint Local Access Forum 12th Annual Report 2015 - 2016 WELCOME TO THE TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE AND KINGSTON UPON HULL JOINT LOCAL ACCESS FORUM (JLAF) Chairman’s Summary This has been an interesting year as we move closer Government funding, we are also exploring other to the opening of the East Yorkshire section of the funding sources to continue and expand the work of England Coast Path. Negotiations between Natural the Local Access Forum. England and landowners have been ongoing and the main change of which we are aware is that the route Between the publication of this report and the end of will go as far as Easington then cut across to the the year, our local authorities will be going through Humber Estuary. One of the big challenges, on safety the due processes of recruiting and appointing new grounds, was determining the route around the old members to the Forum. I would encourage anyone RAF Cowden bombing range but this hopefully seems interested to please contact the Secretariat for more to have now been resolved. information about joining us. Before too long we hope to have access to figures for Our annual report also includes progress updates those sections of the Coast Path already open, showing from both our local authorities relating to work the cost/benefit and spend per head in the local and undertaken in the past year to improve rights of rural communities, which should indicate the long term way and public access. -

Locating the Site of the Battle of Brunanburh (937) V4 by and © Adrian C Grant (1St Version Posted 7Th February 2019, This Revision Posted 5Th August 2019)

Locating the site of the Battle of Brunanburh (937) v4 by and © Adrian C Grant (1st version posted 7th February 2019, this revision posted 5th August 2019) Abstract In this paper I argue that the Battle of Brunanburh (937) took place on the old Roman Road between Brough-on-Humber (Petuaria/Civitas Parisiorum) and South Cave in the East Riding of Yorkshire. This updated version has been triggered both by comments gratefully received from readers of previous drafts and because two alternative candidate sites not wholly inconsistent with my original proposal have come to my attention since version 3 was uploaded. So, whereas the original paper dismissed other proposals mainly by disregarding them, this revision now extends the argument to examine the claims of as many rival sites as I can identify, showing why they are to be discounted. The basis of the positive argument for Brough lies in (a) understanding the military objectives (b) the evidence of the Annals and (c) the relevance of Beverley Minster. It is demonstrated that the place-name evidence is consistent with this site. It is suggested that the huge proportion of church dedications in the area to "All Saints" can be seen as further circumstantial evidence. Preface Following up my researches into the 12 famous battles of "king" Arthur, published in late 2017 ("Arthur: Legend, Logic & Evidence"), my attention turned to the process and timescale of the Anglo-Saxon take over of post-Roman Britain. Amongst other things this caused me to consider the Siege of Lindisfarne and the battles of Catterick, Daegsastan and Caer Greu.