THE HYBRID WING by Jim Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015-2018 Finisher Comparison

2018/17/16/15 R2AK Results Congratulations 2018 R2AK Finishers! Elapsed Time from Victoria Final Team Standings: Start: June 17, 1200 PDT 2016 (1st) 3d 20h 13m, MAD Dog Racing - 31.8’ (9.7m) Cat - Marstrom M32 (3 Crew) 2017 (1st) 4d 3h 5m, Pure & Wild / Freeburd - 28’ (8.5m) Tri - Custom Tetzlaff / Melvin 8.5m Class (3 Crew) 2017 (2nd) 4d 3h 11m, Big Broderna - 30.8’ (9.4m) Tri - Corsair F-31R (4 Crew) 2016 (2nd) 4d 12h 59m, Skiff Foundation Jungle Kitty - 48’ (44’ [13.4m] w/o 4’ bowsprit) Mono - Schooner Creek Fox 44 (8 Crew) 2016 (3rd) 4d 16h 30m, Big Broderna - 30.8’ (9.4m) Tri - Corsair F-31R (3 Crew) 2016 (4th) 4d 18h 6m, Madrona - 40’ (12.2m) Mono - Custom Design (6 Crew) 2016 (5th) 4d 18h 41m, Mail Order Bride - 27.9’ (8.5m) Tri - Farrier F-85SR (4 Crew) 2016 (6th) 4d 20h 34m, Pure & Wild - 27.9’ (8.5m) Tri - Custom Tetzlaff / Melvin 8.5 Class (3 Crew) 2016 (7th) 5d 0h 3m, Un-Cruise Adventures - 26.9’ (8.2m) Tri - Farrier F-25C (3 Crew) 2015 (1st) 5d 1h 55m, Elsie Piddock - 26.9’ (8.2m) Tri - Corsair F-25C (3 Crew) 2017 (3rd) 5d 4h 55m, Bad Kitty - 34’ (10.4m) Cat - Modified Uthoff Custom Catamaran (4 Crew) 2016 (8th) 5d 6h 15m, Turn Point Design - 24’ (7.3m) Cat - Custom Carbon Fiber (3 Crew) 2016 (9th) 5d 16h 18m, It Ain’t Brain Surgery - 30.8’ (9.4m) Tri - Corsair F-31R (3 Crew) 2016 (10th) 6d 6h 44m, Golden Oldies/Ghost Rider - 38’ (11.6m) Cat - Crowther Super Shockwave (6 Crew) 1. -

2017/16/15 R2AK Results

2017/16/15 R2AK Results Congratulations 2017 R2AK Finishers! Elapsed Time from Victoria Final Team Standings: Start: June 11, 1200 PDT 2016 (1st) 3d 20h 13m, Team MAD Dog Racing - 32’ Cat - Marstrom M32 (3 Crew) 1. Team Pure & Wild / Freeburd - 28’ Tri - Custom Tetzlaff / Melvin 8.5m Class (3 Crew) Thursday, June 15, 1405 AKDT (1505 PDT) . 4d 3h 5m 2. Team Big Broderna - 30.8’ Tri - Corsair F31R (4 Crew) Thursday, June 15, 1411 AKDT (1511 PDT) . 4d 3h 11m 2016 (2nd) 4d 12h 59m, Team Skiff Foundation Jungle Kitty - 48’ (44’ w/o 4’ bowsprit) Mono - Schooner Creek Fox 44 (8 Crew) 2016 (3rd) 4d 16h 30m, Team Big Broderna - 31’ Tri - Corsair F31R (3 Crew) 2016 (4th) 4d 18h 6m, Team Madrona - 40’ Mono - Custom Design (6 Crew) 2016 (5th) 4d 18h 41m, Team Mail Order Bride - 28’ Tri - Farrier F-85SR (4 Crew) 2016 (6th) 4d 20h 34m, Team Pure & Wild - 28’ Tri - Custom 8.5 Class (3 Crew) 2016 (7th) 5d 0h 3m, Team Un-Cruise Adventures - 25’ Tri - Farrier F-25C (3 Crew) 2015 (1st) 5d 1h 55m, Team Elsie Piddock - 25’ Tri - Corsair F-25C (3 Crew) 3. Team Bad Kitty - 34’ Cat - Modified Uthoff Custom Catamaran (4 Crew) Friday, June 16, 1555 AKDT (1655 PDT) . 5d 4h 55m 2016 (8th) 5d 6h 15m, Team Turn Point Design - 24’ Cat - Custom Carbon Fiber (3 Crew) 2016 (9th) 5d 16h 18m, Team It Ain’t Brain Surgery - 31’ Tri - Corsair F31R (3 Crew) 2016 (10th) 6d 6h 44m, Team Golden Oldies/Ghost Rider - 38’ Cat - Crowther Super Shockwave (6 Crew) 2016 (11th) 6d 14h 58m, Team Fly - 27’ Tri - Corsair F27 (3 Crew) 2016 (12th) 6d 15h 45m, Team Hot Mess - 30’ Mono - Olson 30 (4 Crew) 2016 (13th) 6d 21h 22m Team Salish Express - 27’ Mono - Express 27 (3 Crew) 4. -

BCMS Newsletter September 2017 2017 Race Results to Date

BCMS Newsletter December 2015 British Columbia Multihull Society September 2017 Spectacular September Long Weekend Sail-In The weather was fabulous over the September Long Weekend at Port Browning. Beautiful sunshine, wind for the race! Great to catch up with everyone. Vicky from Dreamchaser found out why it is called a boom… Ouch! Unless otherwise stated, the views expressed in this newsletter do not represent those of the B.C.M.S., the Directors or the Editor. Contents of the newsletter may be reproduced provided due credit is given to the British Columbia Multihull Society Check out BCMS News @ www.bcms.bc.ca Page 1 of 14 BCMS Newsletter September 2017 2017 Race Results to date Courtesy of: Bruce Campbell https://www.facebook.com/Northwest-Racing-Multis-189212051581313/ updated Sept. 5 1. Southern Straits Race - Apr. 14 - 16 WVYC 8th overall Bad Kitty Ron Tomas custom 34’ cat 12th overall Pturbodactyl John Tulip F31R 2. Semiamhoo Bay Regatta - 3 races Apr. 29 & 30 IYC 1st Bad Kitty Ron Tomas custom 34’ cat 2nd Blue Lightning Mark Gumley F31R 3rd Mustang Sally Rae Simpson 38’ cruising cat 4th Nellie William Crossno 23’ Tremilino 3. Round Thetis Island Race - May 13 1st Dream Chaser Greg Keel F27 2nd Mail Order Bride Wayne Gorrie F85SR 4. Round Salt Spring Island Race - May 20 SISC 1st Dream Chaser Greg Keel F27 DNF Mail Order Bride Wayne Gorrie F85SR DNF Pturbodactyl John Tulip F31R 5. BCMS Fun Race May 21 Port Browning, Pender Island Cruising Div. 1st Dutch Treat Peter Schoonbeck mod. Crowther Bucc. 36 2nd Simone Ken Pepperdine Catamaran 34’ Jeffcat 3rd Mustang Sally Rae Simpson 38’ cruising cat Racing Div. -

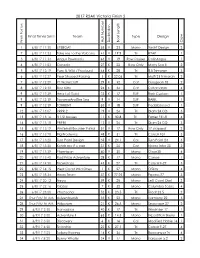

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Epoxyworks 23 Is Also Available As A

® EPOXYWORKS ® Number 23 n Spring 2006 BUILDING, RESTORATION & REPAIR with EPOXY Onne van der Wal In this issue EPOXYWORKS® 1 Scheherazade update Editors Kay Harley, Jennifer Jones A late look at the Hodgdon-built, Bruce King-de- Designer Michael Barker signed, 154' ketch. Subscriptions Kristen Lore 2 The limitations of statues What to do when your shepherd gets cold feet and Contributors W. D. Bertelsen, Tim Botimer, Jason Havel, falls apart under a little stress. Brian Knight, Bruce Niederer, Tom Pawlak, Patrick Ropp, 4 Fabricating an air scoop J. R. Watson and Jeff Wright Using the “lost foam” method to build a custom air Epoxyworks is published twice a year by Gougeon Brothers, scoop for a race car. Inc.,BayCity,MIUSA. 6 Building a masthead fitting Product number 000-605 Building a custom sailboat part with a molded cavity also using the “lost foam” method. ©2006 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Reproduction in any form, in whole or in part, is expressly forbidden without the 8 If you can’t take the heat... written consent of the publisher. An explanation of the effects of high temperatures on cured epoxy and what HDUL really means. Epoxyworks, Gougeon Brothers, WEST SYSTEM,105, 205, 206, 207, 209, 403, 404, 405, 406, 407, 410, Episize, Scarffer, and 10 Rebuilding an International 110 Microlight as used throughout this publication are trade- Tim Botimer wins a national championship after re- marks of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. building a 110 that sailed in the 1941 Nationals. Subscriptions, US and Canada Epoxyworks subscriptions 12 Readers’ projects are FREE to US and Canadian addresses only. -

The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction

The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction Wood and WEST SYSTEM® Materials 5th Edition Meade Gougeon Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Bay City, Michigan Gougeon Brothers, Inc. P.O. Box 100 Patterson Avenue Bay City, Michigan, 48707-0908 Editor: Kay Harley Technical Editors: Brian K. Knight and Tom P. Pawlak Designer: Michael Barker Copyright © 2005, 1985, 1982, 1979 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. P.O. Box 908, Bay City, Michigan 48707, U. S. A. First edition, 1979. Fifth edition, 2005. Except for use in a review, no part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form, or by any means, electronic or manual, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system without prior written approval from Gougeon Brothers, Inc., P.O. Box 908, Bay City, Michigan 48707-0908, U. S. A., 866-937-8797 The techniques suggested in this book are based on many years of practical experience and have worked well in a wide range of applications. However, as Gougeon Brothers, Inc. and WEST SYSTEM, Inc.will have no control over actual fabrication, any user of these techniques should understand that use is at the user’s own risk. Users who purchase WEST SYSTEM® products should be careful to review each product’s specific instructions as to use and warranty provisions. LCCN 00000 ISBN 1-878207-50-4 Cover illustration by Michael Barker. Layout by Golden Graphics, Midland, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America by McKay Press, Inc., Midland, Michigan. Contents Preface . ix Acknowledgments . xi Chapter 1 Introduction–Gougeon Brothers and WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy . -

2019,18,17,16,15 R2AK Results

2019,18,17,16,15 R2AK Results Congratulations 2019 R2AK Finishers! Elapsed Time from Victoria Final Team Standings: Start: June 6, 1200 PDT 2016 (1st) 3d 20h 13m, MAD Dog Racing - 31.8’ (9.7m) Cat - Marstrom M32 (3 Crew) 2017 (1st) 4d 3h 5m, Pure & Wild / Freeburd - 28’ (8.5m) Tri - Cust. Tetzlaff / Melvin 8.5m Class (3 Crew) 2017 (2nd) 4d 3h 11m, Big Broderna - 30.8’ (9.4m) Tri - Corsair F-31R (4 Crew) 1. Angry Beaver - Skiff Sailing Foundation - 40.0’ (12.2m) Mono - Shock 40 (6 Crew) Monday, June 10, 1456 AKDT (1556 PDT) . 4d 3h 56m 2. Pear Shaped Racing - 34.8’ (10.6m) Tri - Chris Cochrane 10.6m Custom (3 Crew) Monday, June 10, 1723 AKDT (1823 PDT) . 4d 6h 23m 2016 (2nd) 4d 12h 59m, Skiff Foundation Jungle Kitty - 48’ (44’ [13.4m] w/o 4’ bowsprit) Mono - Schooner Creek Fox 44 (8 Crew) 3. Shut Up And Drive - 33.2’ (10.1m) Mono - Beneteau Figaro 2 (8 Crew) Tuesday, June 11, 0019 AKDT (0119 PDT) . 4d 13h 19m 4. First Federal’s Team Sail Like A Girl - 31.8’ (9.7m) Mono - Melges 32 (7 Crew) Tuesday, June 11, 0233 AKDT (0333 PDT) . 4d 15h 33m 5. Educated Guess - 24.0’ (7.3m) Mono - Melges 24 (4 Crew) Tuesday, June 11, 0306 AKDT (0406 PDT) . 4d 16h 6m 2016 (3rd) 4d 16h 30m, Big Broderna - 30.8’ (9.4m) Tri - Corsair F-31R (3 Crew) 2016 (4th) 4d 18h 6m, Madrona - 40’ (12.2m) Mono - Custom Design (6 Crew) 2016 (5th) 4d 18h 41m, Mail Order Bride - 27.9’ (8.5m) Tri - Farrier F-85SR (4 Crew) 6. -

2017 R2AK Victoria Finish Results

2017 R2AK Victoria Finish 2 Final Times Set I Team Type Design Hull Number Finish Position Destination Boat Length Crew 1 6/8/17 11:30 LITEBOAT 55 V 23 Mono Yacht Design 2 2 6/8/17 11:33 Take me to the Volcano 41 V 19.9 Tri R2AK 1 3 6/8/17 11:34 Angus Rowboats 63 V 19 Row Cruiser ColinAngus 1 4 6/8/17 11:53 Oaracle 27 K 22 Row Only Merry Sea II 2 5 6/8/17 12:19 Pure & Wild / Freeburd 44 K 28 Tri 8.5 Trimaran 3 6 6/8/17 12:27 Pear Shaped Racing 5 K 22.06 Tri Multi 23 Trimaran 2 7 6/8/17 12:29 PT Watercraft 29 K 32 Cat Gougeon 32 2 8 6/8/17 12:32 Bad Kitty 24 K 34 Cat Catamaran 4 9 6/8/17 12:39 Heart of Gold 23 K 17 SUP Bark-Custom 1 9 6/8/17 12:39 TacomaAndThe Sea 9 V 14 SUP BARK 1 9 6/8/17 12:39 TORRENT 53 V 18 SUP Paddleboard 1 12 6/8/17 13:07 PRPR 2 19 V 24 Tri Diam 24 OD 3 13 6/8/17 13:16 3 1/2 Aussies 11 K 30.8 Tri Farrier F31-R 4 14 6/8/17 13:18 PRPR1 13 V 24 Tri Diam 24 OD 3 15 6/8/17 13:19 Whitehall Boarder Patrol 51 V 17 Row Only 17 slideseat 2 16 6/8/17 13:20 Big Broderna 48 K 31 Tri Corsair F31 3 17 6/8/17 13:20 Turn Point Design 35 V 24.1 Cat Turn Point 24 3 18 6/8/17 13:30 Ketch me if u can 31 K 20 Cat Nacra Inter 20 2 19 6/8/17 13:39 Ptarmigan 60 V 30 Mono Olson30 4 20 6/8/17 13:40 Rod Price Adventure 28 K 17 Mono Canoe 1 21 6/8/17 14:50 Triceratops 45 K 27 Tri Corsair F-27 3 22 6/8/17 16:15 West Coast Wild Ones 1 K 27 Mono O'Day 4 23 6/8/17 18:34 Away Team 37 K 27.25 Mono Express 27 3 24 6/8/17 20:12 Freya 59 K 25 Mono Left Coast Dart 2 25 6/8/17 22:16 Global 7 K 32 Mono Columbia Sabre 4 26 6/8/17 23:00 Phocoena 52 K 23.5 -

Team Name Type Boat Description LOA Skipper Hometown 2019

2019 Tracker Junkie Cheat Sheet # Team Name Type Boat Description LOA Skipper Hometown Crew 7 SoggyKru Cat Malcom Tennant Streaker 24 ft. Dunand Victoria, BC 1 44 Ghost the Coast Kayak Seaward Kayaks Chilco X3 18.5 ft. Kozma Langley, BC 1 48 Oaracle Kayak Seaward Passat G3 Tandem 22 ft Graeme Victoria, BC 2 52 Angry Beaver Mono Schock 40 Matte 40 ft. Pistay Port Ludlow, WA 6 33 Barbarossa Mono Melges 24 24 ft. Kershner Seattle, WA 2 11 Dazed and Confused Mono Olson 30 30 ft. Boland Ponte Vedra Beach, FL 5 12 Educated Guess Mono Melges 24 24 ft. Walker Bellingham, WA 4 41 Funky Dory Mono Swampscott Dory 15.9 ft. Belle Walpole, ME 2 21 High Sea Drifters Mono Olson 30 ft. 30 ft Hocking San Rafael, CA 6 9 Ketchikan Yacht Club Mono Santa Cruz 27 27 ft. 27 ft. Dahl Ketchikan, AK 3 14 M.B.R. (McGuffin Brothers Racing) Mono J24 White 24 ft. McGuffin Salt Spring, BC 4 46 North2Alaska Mono Maryland Fishing Sharpie 25 ft. Veitenhans Port Townsend, WA 6 8 Pitoraq Mono Windward 30 30.25 ft. Heath Victoria, BC 3 18 Quilbillians Mono Miller 27 28 ft. Miller Quilcene, WA 3 51 R2Ache Mono MacGregor 26 30 ft. Jensen Vancouver, BC 2 16 Ripple Mono Santa Cruz 27 27 ft. Stewart Whitefish Bay, WI 5 42 Sail Like a Girl Mono Melges 32 ft. Goussev Bainbridge Island, WA 7 30 Seaforth Expeditions Mono Custom Rower/Sailer 41 ft. McPherson Sechelt, BC 7 6 Shut Up and Drive Mono Beneteau Figaro 2 33 ft. -

Epoxyworks 51 Is Also Available As A

FREE BUILDING, RESTORATION & REPAIR with EPOXY Number 51 Fall 2020 In this issue EPOXYWORKS ® Editor/Designer Jenessa Hilger Managing Editor/Copy Editor Grace Ombry In This Issue Contact/Subscriptions Mari Verhalen Jon Staudacher’s Scientific Approach to Projects 1 Contributors Bill Bauer, Pat Dammer, Rachael Don Gutzmer shares some of the recent projects noted Geerts, Don Gutzmer, Jared Kramer, Mike Lenemen, designer and builder Jon Staudacher has been working Jeff McAffer, Terry Monville, Bruce Schinder on and his innovative solutions. Epoxyworks is published twice a year by Gougeon Brothers, Inc., Bay City, MI, USA. Quality Control: It’s what we do 4 At WEST SYSTEM we take quality control very seriously. Product Number 000-605 We want to be sure you get consistently excellent epoxy © 2020 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Reproduction in any form, every time you pick up a can off the shelf. Here are some in whole or in part, is expressly forbidden without the written of the tests we do to ensure that promise is a reality. consent of the publisher. Epoxyworks is a registered trademark of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Understanding Impact and Abrasion Resistance 6 WEST SYSTEM, 105 Epoxy Resin, 205 Fast Hardener, 206 Slow Hardener, Skid plates take a beating from impacts and 410 Microlight, G/5, G/flex and Six10 are registered trademarks of abrasions on small boats. Here are some things you Gougeon Brothers, Inc. 207 Special Clear Hardener, 209 Extra Slow can do to give your boat the best resistance against Hardener, 422 Barrier Coat Additive and Episize are trademarks of this type of damage. -

2017 R2AK Boat Cheat Sheet 11 33 65 63 37 24 57 48 30 34 42 8 56 6

2017 R2AK Boat Cheat Sheet Team Name Boat Name Type Design Hull Color Sail Color Hull# V-K LOA Crew # 3 1/2 Aussies 11 Pturbodactyl K 30.8 Tri Farrier F31-R White Black 4 Adventourists 33 GIZMO K 22 Mono Harmony 22 White TBD 3 Adventure II 65 Adventure II K 14.5 Mono Expedition Skerry White white 1 Angus Rowboats 63 Row Cruiser K 19 Row Cruiser Colin Angus White w/ Red Deck White w/ red stripes 1 Away Team Spar Trek Mono Express 27 White White w/ carbon 37 K 27.25 y 3 Bad Kitty Bad Kitty Cat Catamaran yellow spinaker 24 K 34 g p 4 Baloo-Water 57 Rowena K 19 Tri Cruiser and grey topside. White/Red 1 Big Broderna 48 Broderna K 31 Tri Corsair F31 White White 3 Bitty Kitty Meow Bitty Kitty Meow Cat NACRA 17 white tan 30 K 17.2 1 Bunny Whaler Bunny Whaler Mono Harpoon 5.2 White Whiten, black, red 34 V 17 pp p g 2 campbell sloop 42 campbell sloop K 17 Tri Angus orange mixed 1 Chum 8 Orca K 17.5 Mono Siren 17 Blue Black 2 Dandies Hobie 18 Cat Hobie White Blue 56 V 18 2 Discovery 6 Catsup K 19.8 Tri and SUP RagWing Racing Sand SUP None 1 Eagle - Take 3 Cetus (The Whale) Kayak Ancient Aleutian White None 58 V 17.5 g y 1 Excellent Adventure 16 Pacific V 17 Mono sloop white with green stripe drifter 3 Freya 59 Freya K 25 Mono Left Coast Dart White black and white 2 Fueled By Stoke Part Deux 50 Hakuna Matata K 17 SUP Ronin multi 1 Fueled On Stoke 49 Ronin K 17 SUP Expedition SUP Multi 1 GAR 17 GAR K 18.4 Tri TriRaid 560 Dark Grey and White White 1 Global Greener Mono Columbia Sabre Super Green White 7 K 32 4 Grace B 18 Grace B K 25.75 Mono Pinky -

BUILDING, RESTORATION & REPAIR with EPOXY Number 46 Spring 2018

FREE BUILDING, RESTORATION & REPAIR with EPOXY Number 46 Spring 2018 In this issue EPOXYWORKS ® Editor/Designer Jenessa Hilger Managing Editor/Copy Editor Grace Ombry In This Issue Contact/Subscriptions Mari Verhalen Contributors Russell Brown, Tom Pawlak, Alan G-wiz! 1 Gurski, Bruce Niederer Doc Wright, Ryan Krafka, Russell Brown bought a G-32, refit it and raced it in Greg Bull, and Don Gutzmer the R2AK. He highlights some of his favorite features about the boat which was originally constructed here at Gougeon Brothers. Epoxyworks is published twice a year by Gougeon Wooden Window Repair 4 Brothers, Inc., Bay City, MI, USA. Window sills, wood sashes and trims often become weathered and rot due to constant exposure to the Product Number 000-605 elements. This article covers our process for fixing the © 2018 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Reproduction in any form, damage and preventing future damage. in whole or in part, is expressly forbidden without the written consent of the publisher. Refinishing a wood strip canoe 6 Epoxyworks is a registered trademark of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Tom shares his process for fairing his wood strip canoe WEST SYSTEM, 105 Epoxy Resin, 205 Fast Hardener, 206 Slow Hardener, while maintaining a clear finish. 410 Microlight, G/5, G/flex and Six10 are registered trademarks of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. 207 Special Clear Hardener, 209 Extra Slow Meade A. Gougeon 8 Hardener, 422 Barrier Coat Additive, Episize and Scarffer are Meade, one of the founders of Gougeon Brothers, trademarks of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. passed away in August. It was his idea to create a magazine to share epoxy projects, tips and ideas.