Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Cover 01-2012.Ppp

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association JANUARY 2012 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Anxious Dxers Camp out on a Snowy New Years Eve Anticipating huge Discounts on DX Equipment at Ozzy’s House of Antennas. Paul Mitschler Happy New DX Year 2012! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info _______________________________________________________________________________________ We’re back. I hope everyone had an enjoyable holiday season! So far I’ve heard of just one Es event just before Christmas that very briefly made it to FM and another Es event that was noticed by Chris Dunne down in Florida that went briefly to FM from Colombia. F2 skip faded away somewhat as the solar flux dropped down to the 130s. So, all in all, December has been mostly uneventful. But keep looking because anything can still happen. We’ve prepared a “State of the Club” message for this issue. -

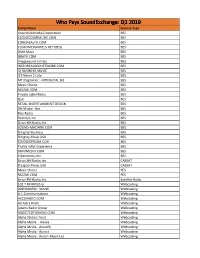

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

Somerset, PA (United States) FM Radio Travel DX

Somerset, PA (United States) FM Radio Travel DX Log Updated 3/13/2019 Click here to view corresponding RDS/HD Radio screenshots from this log http://fmradiodx.wordpress.com/ Freq Calls City of License State Country Date Time Prop Miles ERP HD RDS Audio Information 88.3 WLVV Midland MD USA 3/10/2019 2:02 PM Tr 30 490 "K-Love" - ccm 88.5 WYFU Masontown PA USA 3/10/2019 2:02 PM Tr 52 16,000 area Tr 88.9 WFRJ Johnstown PA USA 3/10/2019 2:03 PM Tr 26 5,500 religious 89.3 WQED-FM Pittsburgh PA USA 3/10/2019 2:03 PM Tr 57 28,000 "Classical 89.3 QED' - classical 89.5 WVDS-FM Petersburg WV USA 3/10/2019 2:03 PM Tr 56 10,000 "West Virginia Public Broadcasting" - public radio 89.7 WQEJ Johnstown PA USA 3/10/2019 2:04 PM Tr 26 8,400 "Classical 89.3 QED' - classical 89.9 WVNP Wheeling WV USA 3/10/2019 2:04 PM Tr 81 25,000 "West Virginia Public Broadcasting" - public radio 90.3 WAIJ Grantsville MD USA 3/10/2019 2:04 PM Tr 21 10,000 religious 90.5 WESA Pittsburgh PA USA 3/10/2019 2:04 PM Tr 59 25,000 "90.5 WESA" - public radio 90.7 WPAI Nanty Glo PA USA 3/10/2019 2:04 PM Tr 37 2,100 "Air 1" - ccm 90.9 WVPM Morgantown WV USA 3/10/2019 2:05 PM Tr 43 5,000 RDS "West Virginia Public Broadcasting" - public radio 91.1 WUFR Bedford PA USA 3/10/2019 2:06 PM Tr 32 2,500 religious 91.3 WYEP-FM Pittsburgh PA USA 3/10/2019 2:06 PM Tr 55 18,000 variety 91.9 WFWM Frostburg MD USA 3/10/2019 2:06 PM Tr 30 1,300 classical 92.1 WJHT Johnstown PA USA 3/10/2019 2:07 PM Tr 26 580 RDS "Hot 92.1" - CHR 92.3 W222AP New Baltimore MD USA 3/10/2019 2:07 PM Tr 12 10 public radio -

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Florence September 19, 2018

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Florence September 19, 2018 The following is a report on the status of communications services in geographic areas impacted by Hurricane Florence as of September 19, 2018 at 11:00 a.m. EDT. This report incorporates network outage data submitted by communications providers to the Federal Communications Commission’s Disaster Information Reporting System (DIRS). DIRS currently covers areas of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia. Note that the operational status of communications services during a disaster may evolve rapidly, and this report represents a snapshot in time. As of today, Hurricane Florence has had an impact on communications, primarily in North Carolina, and to some degree in South Carolina. The following 99 counties are in the current geographic area that is part of DIRS (the “disaster area”). GEORGIA: Appling, Bacon, Bryan, Bulloch, Burke, Candler, Chatham, Effingham, Emanuel, Evans, Jeff Davis, Jefferson, Jenkins, Liberty, Long, Mcintosh, Montgomery, Screven, Tattnall, Toombs, Treutlen, Wayne NORTH CAROLINA: Anson, Beaufort, Bertie, Bladen, Brunswick, Camden, Carteret, Chatham, Chowan, Columbus, Craven, Cumberland, Currituck, Dare, Duplin, Edgecombe, Franklin, Gates, Greene, Halifax, Harnett, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Johnston, Jones, Lee, Lenoir, Martin, Moore, Nash, New Hanover, Northampton, Onslow, Pamlico, Pasquotank, Pender, Perquimans, Pitt, Richmond, Robeson, Sampson, Scotland, Tyrrell, Wake, Washington, Wayne, Wilson SOUTH CAROLINA: Allendale, Bamberg, Barnwell, Beaufort, Berkeley, Calhoun, Charleston, Chesterfield, Clarendon, Colleton, Darlington, Dillon, Dorchester, Florence, Georgetown, Hampton, Horry, Jasper, Kershaw, Lee, Marion, Marlboro, Orangeburg, Richland, Sumter, Williamsburg VIRGINIA: Chesapeake City, Suffolk City, Virginia Beach City The following map shows the counties in the disaster area: As prepared by the Federal Communications Commission: September 19, 2018 11:30 a.m. -

Marvell Fm Download

Marvell fm download the critically acclaimed Marvell FM 1 by the North London trio takes listeners back to the days Downloads ; Listens ; Views Released in , Marvell FM 3 has been praised as the best mixtape to date by the North London Downloads ; Listens ; Views The long-awaited Marvell FM 4 from the UK hip hop trio Marvell Boys has finally dropped for all you Marvell Fans! Look out for features from Chipmunk, Wrecth 32, Sneakbo, JME, Lady Leshurr, Mark Asari, Dot Rotten and many more. Flee free to listen or download the mixtape here on. Marvell FM 2 also has a feature from N.A.S.T.Y Krus Griminal as well as a remix to Aggros Free Yard Downloads ; Listens ; Views Click Here To Download. Marvell FM 3. The newest installment from the marvell boys featuring their hit single rhythm & flow. Marvell Fm 3 Mixtape. CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD MARVELL FM 2 COMING SOON AUGUST 17TH, STAY LOCKED INTO THE COUNTDOWN. Marvell - Marvell FM 3 (Free Download). February 04, 0 Comments. A week later, it's out, but still late. The Marvell fan boys and girls were going mad in. Don't violate Murder dem Request line Marvell mandem Outro Going in 32's Marvell vs Westwood. DOWNLOAD: Marvell – Marvell FM. Creme de le creme Go outta control 3 way Marvell boys Outro Freestyle bonus (featuring Ike The Kidd). DOWNLOAD: Marvell – Marvell FM 4. Successful (Official UK remix) (featuring Trey Songs) Going in 32's part 2 (featuring Griminal) Outro 09 free yard. DOWNLOAD: Marvell – Marvell FM 2. This thread is an automatic RSS feed from our home page and it is best viewed in it's original format here. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Merry Christmas! Visit Us At

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association DECEMBER 2010 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers FLEA MARKET FIND Andria Radio “Sharp Focus” Television/Radio The AUVIO HD TUNER IS IT ANY GOOD? Merry Christmas! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info DECEMBER 2010 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 4 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 9 secure way to join or renew your membership FCC Facilities Changes 13 in the WTFDA. Just logon to Paypal and send Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 16 your dues to [email protected]. Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 19 Use the email address above to either join Southern FM DX…John Zondlo 25 the WTFDA or renew your membership in Coast to Coast TV DX…Nick Langan 26 North America’s only TV and DX organization. -

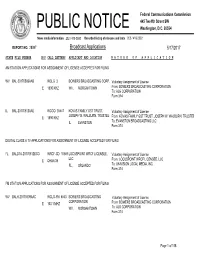

Broadcast Applications 5/17/2017

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28987 Broadcast Applications 5/17/2017 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WV BAL-20170509AAB WCLG 3 BOWERS BROADCASTING CORP. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1300 KHZ WV , MORGANTOWN From: BOWERS BROADCASTING CORPORATION To: AJG CORPORATION Form 314 IL BAL-20170512AAE WCGO 35447 KOVAS FAMILY GST TRUST, Voluntary Assignment of License JOSEPH W. WALBURN, TRUSTEE E 1590 KHZ From: KOVAS FAMILY GST TRUST, JOSEPH W. WALBURN, TRUSTEE IL , EVANSTON To: EVANSTON BROADCASTING LLC Form 314 DIGITAL CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING FL BALDTA-20170512BCO WRCF-CD 10549 LOCUSPOINT WRCF LICENSEE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E CHAN-35 From: LOCUSPOINT WRCF LICENSEE, LLC FL , ORLANDO To: UNIVISION LOCAL MEDIA, INC. Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WV BALH-20170509AAC WCLG-FM 6553 BOWERS BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License CORPORATION E 100.1 MHZ From: BOWERS BROADCASTING CORPORATION WV , MORGANTOWN To: AJG CORPORATION Form 314 Page 1 of 158 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

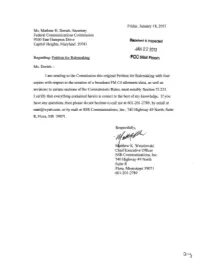

Class C4 Allocation

Friday, January 18, 2013 Ms. Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary Federal Communications Commission 9300 East Hampton Drive Aeeelved & ln:5~eeted Capitol Heights, Maryland 20743 JAN 2 2 2013 Regarding: Petition for Rulemaking FCC Mail Room Ms. Dortch- I am sending to the Commission this original Petition for Rulemaking with four copies with respect to the creation of a broadcast FM C4 allotment class, as well as revisions to certain sections ofthe Commission's Rules, most notably Section 73.215. I certify that everything contained herein is correct to the best of my knowledge. If you have any questions, then please do not hesitate to call me at 601-201-2789, by email at [email protected], or by mail at SSR Communications, Inc., 740 Highway 49 North, Suite R, Flora, MS 39071. Respectfully, -u/,;Pf~· .J~hew K. Wesolowski Chief Executive Officer SSR Communications, Inc. 740 Highway 49 North SuiteR Flora, Mississippi 39071 601-201-2789 .. Received & ln~pected JAN 2 2 2013 Before the FCC Mail Room FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Docket No. MB ----- Amendment of Sections 73.207, 73.210, ) RM------ 73.211, 73.215, and 73.3573 ofthe ) Commission's Rules related to Minimum ) Distance Separation Between Stations, ) Station Classes, Power and Antenna Height ) Requirements, Contour Protection for Short ) Spaced FM Assignments, and Processing ) FM Broadcast Station Applications ) To the Commission PETITION FOR RULEMAKING Matthew K. Wesolowski Chief Executive Officer SSR Communications, Inc. 740 U.S. Highway 49 North SuiteR Flora, MS 39071 (601) 201-2789 [email protected] January 18, 2013 i :,J. -

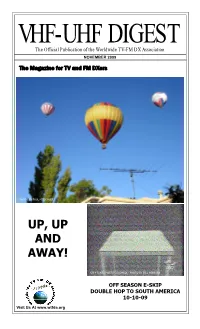

Up, up and Away!

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association NOVEMBER 2009 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers PHOTO BY PAUL MITSCHLER UP, UP AND AWAY! CH 4 SANTA MARTA COLOMBIA - PHOTO BY BILL HEPBURN OFF SEASON E-SKIP DOUBLE HOP TO SOUTH AMERICA 10-10-09 Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info NOVEMBER 2009 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Finally! For those of you online with an email Mailbox 3 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and TV News…Doug Smith 4 secure way to join or renew your membership FM News…Bill Hale 11 in the WTFDA from our page at: Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 22 http://www.wtfda.org/join.html FM South…John Zondlo 24 You can now renew either paper VUD Eastern TV DX…Nick Langan 25 membership or your online eVUD membership Western TV DX…Nick Langan 27 at one convenient stop. -

Broadcast Applications 2/15/2007

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 26424 Broadcast Applications 2/15/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED TN BRED-20040331ANB WDVX 14724 CUMBERLAND COMMUNITIES Amendment filed 02/12/2007 COMMUNICATIONS E 89.9 MHZ CORPORATION TN , CLINTON FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED TN BRFT-20040331ANC W291AA 11058 CUMBERLAND COMMUNITIES Amendment filed 02/12/2007 COMMUNICATIONS E 106.1 MHZ CORPORATION TN , KNOXVILLE TN BRFT-20040331AND W275AD 82561 CUMBERLAND COMMUNITIES Amendment filed 02/12/2007 COMMUNICATIONS E 102.9 MHZ CORPORATION TN , KNOXVILLE AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING MI BAL-20070212AAT WWKK 79338 STONE COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 750 KHZ MI , PETOSKEY From: STONE COMMUNICATIONS, INC. To: FORT BEND BROADCASTING COMPANY Form 314 Page 1 of 141 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 26424 Broadcast Applications 2/15/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING MO BAL-20070212ACM KCHI 63377 DANIEL D. -

Attachment B - Second Adjacent Waiver Requests FCC 14-132

WLUP-FM, WFMT(FM) WUBU(FM) WVEZ(FM) N E R 1 of 6 10865 Attachment B - Second Adjacent Waiver Requests FCC 14-132 12 73A 20131115ABV3 20131115ABV 73A 20131107AJD4 CROMWELL 20131107AJD5 MANCHESTER6 78 20131113BMP7 CT 20131113BMP 78 20131112CCS CT TAKOMA PARK SOCIETY OF THE MISSIONARIES HOLY WDRC-FM 8 78 20131112CCS 20131114AKR MANCHESTER COMMUNITY COLLEGE9 20131114AKR WASHINGTON MD WASHINGTON HISTORIC TAKOMA INC. 80 20131113BOBDC 80 20131113BOB 20131113BMQDC WDRC-FM HR-57 FOUNDATION HOCKESSIN 20131113BMQ THE WASHINGTON PEACE CENTER WILMINGTON DE DE AFRO-AMERICAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY SANFORD SCHOOL WKYS(FM), WIAD(FM) WBEN-FM WKYS(FM), WIAD(FM) WKYS(FM), WIAD(FM) WBEN-FM 15 1617 15218 20131114BNK 20131114BNK 15219 20131114ADR CHICAGO 20131114ADR 15220 20131114ABC CHICAGO 20131114ABC21 CHICAGO 15322 20131114BDD 20131114BDD23 IL EL PASO 15424 20131115ASO IL SOUND OF HOPE RADIO NFP 154 20131115ASO25 20131115AVQ IL URBANMEDIA ONE CHICAGO 20131115AVQ26 MORTON COLLEGE CHICAGO 16327 20131114AHR IL 20131114AHR28 EVANSVILLE TRINITY EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION 16629 20131114BBG IL 166 20131114BBG30 IL 20131114BFX ROOTS & CULTURE SOUTH BEND IN 20131114BFX31 WFMT(FM), WUSN(FM) PUBLIC MEDIA INSTITUTE WJEK(FM), WQQB(FM) SOUTH BEND 171 LEGION OF MARY COMITIUM32 20131023AAA 20131023AAA 171 IN33 20131112AZF LOUISVILLE HOLY CROSS COLLEGE, INC.34 20131112AZF IN 174 LOUISVILLE35 SISTERS OF ST. FRANCIS PERPETUAL ADO 20131114AFB WFMT(FM), WUSN(FM) 174 20131114AFB36 KY 20131114AOU WFMT(FM), WUSN(FM) LOUISVILLE 20131114AOU CRESCENT HILL RADIO INC.37 LOUISVILLE KY 17538 20131112AWI FELLOWSHIP OF RECONCILIATION LOUISVILL WIKY-FM WOJO(FM), WCFS-FM 175 20131112AWI39 20131112AMA KY 20131112AMA COVINGTON KY ART FM, INC. COVINGTON WOJO(FM), WCFS-FM WUBU(FM) SQUALLIS PUPPETEERS INC. 183 20131112AAF 20131112AAF KY AUBURNDALE KY 24-7 BROADCASTING, INC.