Getting Here from There: Steamboat Travel to Mount Desert Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Settlement-Driven, Multiscale Demographic Patterns of Large Benthic Decapods in the Gulf of Maine

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, L 241 (1999) 107±136 Settlement-driven, multiscale demographic patterns of large benthic decapods in the Gulf of Maine Alvaro T. Palmaa,* , Robert S. Steneck b , Carl J. Wilson b aDepartamento EcologõaÂÂ, Ponti®cia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Alameda 340, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile bIra C. Darling Marine Center, School of Marine Sciences, University of Maine, Walpole, ME 04573, USA Received 3 November 1998; received in revised form 30 April 1999; accepted 5 May 1999 Abstract Three decapod species in the Gulf of Maine (American lobster Homarus americanus Milne Edwards, 1837, rock crab Cancer irroratus Say, 1817, and Jonah crab Cancer borealis Stimpson, 1859) were investigated to determine how their patterns of settlement and post-settlement abundance varied at different spatial and temporal scales. Spatial scales ranged from centimeters to hundreds of kilometers. Abundances of newly settled and older (sum of several cohorts) individuals were measured at different substrata, depths, sites within and among widely spaced regions, and along estuarine gradients. Temporal scales ranged from weekly censuses of new settlers within a season to inter-annual comparisons of settlement strengths. Over the scales considered here, only lobsters and rock crabs were consistently abundant in their early post- settlement stages. Compared to rock crabs, lobsters settled at lower densities but in speci®c habitats and over a narrower range of conditions. The abundance and distribution of older individuals of both species were, however, similar at all scales. This is consistent with previous observations that, by virtue of high fecundity, rock crabs have high rates of settlement, but do not discriminate among habitats, and suffer high levels of post-settlement mortality relative to lobsters. -

The Propulsion of Sea Ships – in the Past, Present and Future –

The Propulsion of Sea Ships – in the Past, Present and Future – (Speech by Bernd Röder on the occasion of the VHT General Meeting on 11.12.2008) To prepare for today’s topic, more specifically for the topic: ship propulsion of the future, I did what every reasonable person would have done in my situation if he should have a look into the future – I dug out our VHT crystal ball. As you know, our crystal ball is a reliable and cost-efficient resource which we have been using for a long time with great suc- cess. Among other things, we’ve been using it to provide you with the repair costs or their duration or the probable claims experience of a policy, etc. or to create short-term damage statistics, as well. So, I asked the crystal ball: What does ship propulsion of the future look like? Every future and all statistics lie in the crystal ball I must, however, admit that what I saw there was somewhat irritating, and it led me to only the one conclusion – namely, that we’re taking a look into the very distant future at a time in which humanity has not only used up all of the oil reserves but also the entire wind. This time, we’re not really going to get any further with the crystal ball. Ship propulsion of the future or 'back to the roots'? But, sometimes it helps to have a look into the past to be able to say something about the fu- ture. According to the principle, draw a line connecting the distant past to today and simply extend it into the future. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX best, 9–10 AITO (Association of Blue Hill, 186–187 Independent Tour Brunswick and Bath, Operators), 48 AA (American Automobile A 138–139 Allagash River, 271 Association), 282 Camden, 166–170 Allagash Wilderness AARP, 46 Castine, 179–180 Waterway, 271 Abacus Gallery (Portland), 121 Deer Isle, 181–183 Allen & Walker Antiques Abbe Museum (Acadia Downeast coast, 249–255 (Portland), 122 National Park), 200 Freeport, 132–134 Alternative Market (Bar Abbe Museum (Bar Harbor), Grand Manan Island, Harbor), 220 217–218 280–281 Amaryllis Clothing Co. Acadia Bike & Canoe (Bar green-friendly, 49 (Portland), 122 Harbor), 202 Harpswell Peninsula, Amato’s (Portland), 111 Acadia Drive (St. Andrews), 141–142 American Airlines 275 The Kennebunks, 98–102 Vacations, 50 Acadia Mountain, 203 Kittery and the Yorks, American Automobile Asso- Acadia Mountain Guides, 203 81–82 ciation (AAA), 282 Acadia National Park, 5, 6, Monhegan Island, 153 American Express, 282 192, 194–216 Mount Desert Island, emergency number, 285 avoiding crowds in, 197 230–231 traveler’s checks, 43 biking, 192, 201–202 New Brunswick, 255 American Lighthouse carriage roads, 195 New Harbor, 150–151 Foundation, 25 driving tour, 199–201 Ogunquit, 87–91 American Revolution, 15–16 entry points and fees, 197 Portland, 107–110 America the Beautiful Access getting around, 196–197 Portsmouth (New Hamp- Pass, 45–46 guided tours, 197 shire), 261–263 America the Beautiful Senior hiking, 202–203 Rockland, 159–160 Pass, 46–47 nature -

Ewa Beach, Died Dec. 23, 2000. Born in San Jose, Calif

B DORI LOUISE BAANG, 38, of ‘Ewa Beach, died Dec. 23, 2000. Born in San Jose, Calif. Survived by husband, Alfred; daughter, Katrina Weaver; son, Joseph Perez; stepsons, Alfred, Richard, Simon, Chad, Damien and Justin; nine grandchildren; mother, Charlotte Young; stepfather, Samuel Young; brother, Joe Allie; grandparents, John and Lorraine Kemmere. Visitation 11 a.m. to noon Saturday at 91-1009D Renton Road; service noon. No flowers. Casual attire. Arrangements by Nuuanu Mortuary. ELECIO RAMIREZ BABILA, 86, of Ewa Beach, died March 5, 2000. Born in Bangui, Ilocos Norte, Philippines. A member of the Bangui Association and Hinabagayan Organization. Survived by wife, Dionicia; son, Robert; daughters, Norma Valdez, Sally Caras and Elizabeth Bernades; 13 grandchildren; 14 great- grandchildren. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Monday at Immaculate Conception Church, Mass 7 p.m. Visitation also 9 a.m. Tuesday at Mililani Memorial Park mauka chapel, service 10:30 a.m.; burial 11 a.m. Casual attire. JAMES SUR SUNG BAC, 80, of Honolulu, died June 16, 2000. Born in Kealakekua, Hawai‘i. Retired from Army and a member of Disabled American Veterans. Survived by wife, Itsuyo; sons, James and Joseph; sister, Nancy; two grandchildren. Service held. Arrangements by Nu‘uanu Memorial Park Mortuary. CLARA TORRES BACIO, 85, of Makaweli, Kaua‘i, died Dec. 20, 2000. Born in Hilo, Hawai‘i. A homemaker. Survived by sons, Peter Kinores, Raymond Kinores, Walter Bacio, Gary Koloa and Paul Bacio; daughters, Lucille Ayala, Margaret Kinores, Joanne Quiocho and Donna Igaya; 26 grandchildren; 15 great-grandchildren; four great-great-grandchildren. Visitation from 8:30 a.m. -

Spanish American, 06-27-1908 Roy Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico Historical Newspapers New Mexico) 6-27-1908 Spanish American, 06-27-1908 Roy Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news Recommended Citation Roy Pub. Co.. "Spanish American, 06-27-1908." (1908). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news/91 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico) by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. US0MMB fálVaai 03DQR Of JO The Spanish American VOL JY. ROY, MORA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE, 27, 1908, NO. 23 WILL CELEBRATE Ball In Honor of Miss Cane. SOMETHING DOING Water Works Meeting Last Friday evening at Bushke- - The Roy Water Works Co. held vitz Hall a dance complimentary to their meeting in the new Bushkevitz Miss Beulah of was giv- A Good Base Ball Game and Other Cane, Colmor, hall on Wednesday evening, June 24. Horse Stealing and a Genuine Old- - en by L. E. Aldredge and Roy Wood. The stockholders were nearly all pres- Closing the Day Amusements. About fifteen couples were present and Fashioned "Hold Up" Takes ent. Chairman Goodman called the With A Grand Ball. themujic furnished by Messers Hanson stockhold- Place in Roy. meeting to order, the Krause and Stanton together with the ers discussed various plans for the to smooth floor made the evenintr pass operation of the Roy Water Works The committee have decided give Our little town is composed of a Bush-kevit- all too quickly although the weather System. -

AN INCREDIBLE JOURNEY ACROSS MAINE ► 10 DAY SAMPLE ITINERARY ACROSS MAINE ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM DESTINATION 02 Superyacht MAINE ITINERARY

H H H H H AN INCREDIBLE JOURNEY ACROSS MAINE ► 10 DAY SAMPLE ITINERARY ACROSS MAINE ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM DESTINATION 02 superyacht MAINE ITINERARY Accommodation 1 Master, 2 Vip, 1 Double, 1 Twin Specifications Length 161’ (49m) Beam 28’ (8.5m) Draft 8 (2.5m) Built Trinity Yachts Year 2005/2015 Engines 2 x Caterpillar 3516B-HD Cruising Speed 20/23 knots Tender + Toys: Towed tender 1 Nautica 18-foot tender with 150hp engine 1 40’ Seahunter towable tender 2 three-person WaveRunners The 161-foot (49.07m) luxury Trinity superyacht ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM is reputed as one 2 Seabobs ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM of the fastest yachts in her size range on the open seas. Not only is she quick, ZOOM 2 Paddleboards 161’ (49M) : TRINITY YACHTS : 2005/2015 ZOOM ZOOM also boasts impeccable style and grace. Snorkeling gear 10 GUESTS : 05 CABINS : 09 CREW Water skis Under the command of Captain Mike Finnegan, who previously ran the owner’s Wakeboard Alaskan yacht SERENGETI, you will enjoy ultimate luxury while cruising The Kneeboard Bahamas, Caribbean and New England on board this resplendent yacht. ZOOM ZOOM Inflatables ZOOM already possesses a successful charter history and is the perfect yacht for Fishing gear Spinning bike your next luxury holiday. Free weights and bench Waterslide Guests who enjoy the water will be delighted by ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM’s extensive toy inventory. She features a towable tender, an 18-foot Nautica with 150hp engine, two three-person WaveRunners, two Seabobs, snorkeling gear, water skis, a wakeboard, a kneeboard, inflatables and fishing gear. ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM DESTINATION 03 superyacht MAINE ITINERARY 10 DAYS MAINE ITINERARY Day 1 PORTLAND Pick up in Portland, ME- Maine’s largest city is an active seaport for ocean going vessels. -

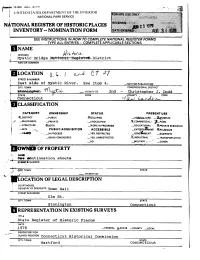

National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form

JEoua^lo 10-300 REV. (9/77) ! UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES i INVENTORY-NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS \UHOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS ____ INAME HISTORIC Mystic Bridge National RegiaLeg- District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER East side of Mystic River. See Item 4. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN1 ^* CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF 2nd - Christopher J. Dodd STATE V CODE A XDUNTY , CODE Connecticut ^J CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _AoajauLiu RS , ,,., S^USEUM X — BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED , ^COMMERCIAL' ^—PAftK: —STRUCTURE X.BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL XpfljvATE RESIDENCE _ SITE v^ PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —OBJMgi ^ N _ IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED > _ GQVElifMENF ' —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED ^.INDUSTRIAL " —TRANSPORTATION —NO ' ^MILITARY V • --'' —OTHER: lOOWNEl OF PROPERTY i See atibntinuation sheets l" STWilTA NUMBER STATE ^ '"'..y' — VICINITY OF VOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Hall STREET & NUMBER Elm St. CITY. TOWN STATE Stoning ton Connecticut REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS State Register of Historic Places DATE 1978 FEDERAL X-STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Connecticut Historical Commission CITY. TOWN STATE . Hartford Connecticut Fori^N" 10-^.Oa (Hev 10 74) UNIThD STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM Mystic Bridge District Mystic, CT CONTINUATION SHEET Prop. Owners . ITEM NUMBER 4 PAGE 1 All addresses are Mystic, CT 06355 unless otherwise noted. Property address and mailing address of owner(s) are the same unless ad ditional (mailing) address is given. -

01 Why Did the United States Enter World War I

DBQ Why did the United States Enter World War I? DIRECTIONS: Read all the following documents and answer the questions in full sentences on a separate sheet of paper. Label each set of questions with the title and number of the document first. Be sure that your answers include specific outside information, details, and analysis. You may consult your class notes, homework, or textbook for help with any question. Whatever you do not finish in class you will have for homework. Document 1 The Lusitania, The Arabic Pledge, The Sussex Pledge and Unrestricted Submarine Warfare On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British ship Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. The Germans attacked the Lusitania without warning, leading to the deaths of 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. President Woodrow Wilson, outraged at Germany’s violation of the United States’ neutral rights, threatened to end diplomacy with Germany. Still, many Americans opposed war, and a large number of German-Americans favored the Central Powers. Germany continued submarine warfare. In August of 1915, another U-boat torpedoed the British passenger liner Arabic, killing approximately forty passengers and crew, including two Americans. Afraid that the U.S. might now enter the war on the side of the Allied Powers, the German government issued the Arabic Pledge in 1915. Germany promised that it would warn non-military ships thirty minutes before it sank them. This would allow passengers and crew time to escape safely on lifeboats. Germany, though, broke the Arabic Pledge in March of 1916, when a U-boat torpedoed the French ship Sussex. -

Little Cranberry Island in 1870 and the 1880S

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine (Islesford Historical Museum, 1969, Acadia National Park) (The Blue Duck, 1916, Acadia National Park) Off the jagged, rocky coast of Maine lie approximately 5,000 islands ranging in size from ledge outcroppings to the 80,000 acre Mount Desert Island. During the mid-18th century many of these islands began to be inhabited by settlers eager to take advantage of this interface between land and sea. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine Living on an island was not easy, however. The granite islands have a very thin layer of topsoil that is usually highly acidic due to the spruce forests dominating the coastal vegetation. Weather conditions are harsh. Summers are often cool with periods of fog and rain, and winters--although milder along the coast than inland--bring pounding storms with 60-mile-per-hour winds and waves 20 to 25 feet high. Since all trading, freight- shipping, and transportation was by water, such conditions could isolate islanders for long periods of time. On a calm day, the two-and-one-half-mile boat trip from Mount Desert Island to Little Cranberry Island takes approximately 20 minutes. As the boat winds through the fishing boats in the protected harbor and approaches the dock, two buildings command the eye's attention. -

History of Maine - History Index - MHS Kathy Amoroso

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 2019 History of Maine - History Index - MHS Kathy Amoroso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Amoroso, Kathy, "History of Maine - History Index - MHS" (2019). Maine History Documents. 220. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/220 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Index to Maine History publication Vol. 9 - 12 Maine Historical Society Newsletter 13 - 33 Maine Historical Society Quarterly 34 – present Maine History Vol. 9 – 51.1 1969 - 2017 1 A a' Becket, Maria, J.C., landscape painter, 45:203–231 Abandonment of settlement Besse Farm, Kennebec County, 44:77–102 and reforestation on Long Island, Maine (case study), 44:50–76 Schoodic Point, 45:97–122 The Abenaki, by Calloway (rev.), 30:21–23 Abenakis. see under Native Americans Abolitionists/abolitionism in Maine, 17:188–194 antislavery movement, 1833-1855 (book review), 10:84–87 Liberty Party, 1840-1848, politics of antislavery, 19:135–176 Maine Antislavery Society, 9:33–38 view of the South, antislavery newspapers (1838-1855), 25:2–21 Abortion, in rural communities, 1904-1931, 51:5–28 Above the Gravel Bar: The Indian Canoe Routes of Maine, by Cook (rev.), 25:183–185 Academy for Educational development (AED), and development of UMaine system, 50(Summer 2016):32–41, 45–46 Acadia book reviews, 21:227–229, 30:11–13, 36:57–58, 41:183–185 farming in St. -

ICE FESTIVAL A.M

DAILY ACTIVITIES VISIT A WORKING SHIPYARD DON’T MISS THESE Mayflower II, which is owned by Plimoth Plantation, All INDOOR SOCK SKATING RINK 11:30 LEARN ABOUT PEMMICAN – is in the final stages of a multi-year restoration. UPCOMING EVENTS Day The Galley THE ULTIMATE SURVIVAL FOOD She is scheduled to depart in spring of 2020: the Buckingham-Hall House 11 AND PROGRAMS! All J.M.W. TURNER BINGO 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival. Day Collins Gallery, Sherman Zwicker, which is owned by the not-for- ADVENTURE SERIES 12:30 MUSIC OF THE SEA AND SHORE ☺ Tickets still available! Thompson Building 1 profit Maritime Foundation, was once part of the Chandlery 26 proud Grand Banks fleet that fished the abundant February 20, March 19, April 16 All BUILD A TOY BOAT KEEPSAKE ☺ but turbulent North Atlantic for cod. Today she is a BEHIND THE CANVAS Day Ages 4 and older; 12:45- POP-UP WINTER ART ACTIVITY ☺ rare surviving example of a transition vessel A special program for art lovers. $5 per boat (cash only) 2:30 P.R. Mallory 4 (from sail to diesel power) and is thus equipped February 22, March 21, April 4 John Gardner Boat Shop Annex 38 with smaller masts and sails that were used less 1:00 STORYTIME WITH NEWFOUNDLANDS ☺ for power and more for stability. She is undergoing SATURDAY WINTER TREATS: PUDDING AND PIES 10:00- ICE SCULPTURE DEMONSTRATION seasonal restoration and maintenance and will Children’s Museum 10 February 29 12:00 (weather permitting) return to her home berth in New York City where SUNDAY, Village Green she is the home to “Grand Banks,” a celebrated MONDAY, The Common INTRODUCTION TO HALF MODEL 1:00 RÉSONANCES BORÉALES* oyster bar. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse.