Joins the Perkins Library: Collecting to Support Persuasion in Architectural Design and History William B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force University of Texas at Austin April 2, 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Inputs to the Task Force ......................................................................................................... 6 Charge 1 ................................................................................................................................ 9 Offsite Storage, Cooperative Collection Management, and Print Preservation .................................9 Closure and Consolidation of Branch Libraries ............................................................................... 10 Redesign of Library Facilities Housing Academic and Research Collections ..................................... 10 Proliferation of Digital Resources and Hybrid Collections .............................................................. 11 Discovery Mechanisms ................................................................................................................. 12 Charge 2 .............................................................................................................................. 14 Size of the Fine Arts Library Collection .......................................................................................... 14 Use of the Fine Arts -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Kahn at Penn

Kahn at Penn Louis I. Kahn is widely known as an architect of powerful buildings. But although much has been said about his buildings, almost nothing has been written about Kahn as an unconventional teacher and philosopher whose influence on his students was far-reaching. Teaching was vitally important for Kahn, and through his Master’s Class at the University of Pennsylvania, he exerted a significant effect on the future course of architectural practice and education. This book is a critical, in-depth study of Kahn’s philosophy of education and his unique pedagogy. It is the first extensive and comprehensive investi- gation of the Kahn Master’s Class as seen through the eyes of his graduate students at Penn. James F. Williamson is a Professor of Architecture at the University of Memphis and has also taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, Drexel University, and Rhodes College. He holds two Master of Architecture degrees from Penn, where he was a student in Louis Kahn’s Master’s Class of 1974. He was later an Associate with Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates. For over thirty years he practiced as a principal in his own firm in Memphis with special interests in religious and institutional architecture. Williamson was elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in recognition of his contributions in architectural design and education. He is the recipient of the 2014 AIA Edward S. Frey Award for career contribu- tions to religious architecture and support of the allied arts. Routledge Research in Architecture The Routledge Research in Architecture series provides the reader with the latest scholarship in the field of architecture. -

Download Issue As

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday July 16, 2019 Volume 66 Number 1 www.upenn.edu/almanac The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research: $12 Million Funding for Major Expansion of Gene Therapy New Center at Penn to Study Radiation Therapy and Immune Signaling Collaboration Between Amicus Therapeutics and Penn The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research radiation oncology in Penn’s Perelman School announced that it has awarded a grant of $12 of Medicine. The primary efforts of the center Amicus Therapeutics and the Perelman million to establish The Mark Foundation Cen- will comprise five key projects that converge School of Medicine at the University of Penn- ter for Immunotherapy, Immune Signaling and on understanding the signaling pathways elic- sylvania announced a major expansion to their Radiation at the University of Pennsylvania. ited by radiation therapy and how those path- collaboration with rights to pursue collaborative The Center will bring together cross-depart- ways can be exploited therapeutically to enable research and development of novel gene thera- mental teams of basic scientists and clinical re- the immune system to recognize and eradicate pies for lysosomal disorders (LDs) and 12 addi- searchers who will focus on better understand- cancer. tional rare diseases. The collaboration has been ing the interconnected relationships between “These projects have the chance to change expanded from three to six programs for rare advances in radiation therapy, important signal- the paradigm when it comes to cancer treat- genetic diseases and now includes: Pompe dis- ing pathways in cancer and immune cells, and ment,” said Dr. Minn. “Understanding impor- ease, Fabry disease, CDKL5 deficiency disorder the immune system’s ability to effectively con- tant and potentially targetable mechanisms of (CDD), Niemann-Pick Type C (NPC), next gen- trol cancer. -

Faith Reforming

Reforming Faith by Design Frank Furness’ Architecture and Spiritual Pluralism among Philadelphia’s Jews and Unitarians Matthew F. Singer Philadelphia never saw anything like it. The strange structure took shape between 1868 and 1871 on the southeast corner of North Broad and Mount Vernon streets, in the middle of a developing residential neighborhood for a newly rising upper middle class. With it came a rather alien addition to the city’s skyline: a boldly striped onion dome capping an octagonal Moorish-style minaret that flared outward as it rose skyward. Moorish horseshoe arches crowned three front entrances. The massive central At North Broad and Mount Vernon streets, Rodeph Shalom’s first purpose-built temple—de- doorway was topped with a steep gable signed by Frank Furness—announced the growing presence and aspirations of the newly developed neighborhood’s prospering German Jewish community. beneath a Gothic rose window that, in HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA turn, sat within another Moorish horse- shoe. Composed of alternating bands of phia. In a city of red-brick rowhouses built full Jewish emancipation and equality and yellow and red sandstone, the arches’ halo- primarily in neoclassical styles, Rodeph sparked new spasms of anti-Semitism. like tops appeared to radiate from central Shalom’s new temple mixed Islamic, Pedestrians gazing upon Rodeph disks incised with abstracted floral shapes. Byzantine and Gothic elements. Shalom may have wondered whether their Buttresses shored the sides of the building, Founded in 1795 as the first Ashkenazi wandering minds conjured an appari- which stood tall and vertical like a Gothic (Central and Eastern European) Jewish tion from a faraway time and place. -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

From Philly, with Love a Leader in Arts, Industry, and Inspiration

From Philly, With Love A leader in arts, industry, and inspiration eople say that you can find inspira- landscaped city park, plus countless smaller that brought America its first art institute con- in Chester County’s Brandywine Valley — and Above: The Philadel- ones; five major league sports teams; and more tinues to break boundaries with events like we’re not talking humdrum suburbs. “Much phia skyline ties tion anywhere, but in Philadelphia, together the city’s public art than any other U.S. city. Philadelphia Open Studio Tours (POST), like the great cities of Europe, whose surround- storied past and bright inspiration is everywhere. It has Visitors to Philadelphia go beyond its inviting audiences to visit more than 300 art- ing towns and villages are intrinsically tied to present. been true of the city for genera- impressive superlatives to really experience ists’ workspaces in 20 neighborhoods. Get up the landscape, Philadelphia and the Brandy- its personality. In one day, they can stroll the close and personal with Philadelphia’s most wine Valley combine for an inspirational tions, and it’s especially true today. culturally rich Ben Franklin Parkway, see a creative. destination,” says Blair Mahoney, executive P ballet, bounce from blues bar to luxe lounge director of the Chester County CVB. to brew-centric pub, and eat that famous Major Players This inspiration takes form in vibrant and cheesesteak. Philadelphia’s specialty? Variety. The Eagles, Flyers, Sixers, and Phillies are Lifelong Learning By HannaH growing neighborhoods, immersive museums The most inspiring thing in Philadelphia quintessentially American teams. But when the Eighty colleges and 300,000 students give SHerk that stun inside and out, and forward-thinking can’t be found on a map or in a visitors’ guide Philadelphia Union soccer team joined the Philadelphia that energetic, college-town schools that shape professional fields. -

PAS WEEKLY UPDATE WEEK of May 7, 2018 Mr

PAS WEEKLY UPDATE WEEK OF May 7, 2018 Mr. Farrell, Principal Thank you for coming out to our inaugural art celebraton last Thursday– Upcoming Events Celebratng the Art of Penn Alexander. We thank our planning commitee and the Home & School Associaton (HSA) Teacher Appreciaton Week for their commitment to Art programming at PAS! Monday, May 7th- Friday, May 11th Home & School Associaton (HSA) Meetng School District Parent & Guardian Survey We would love to hear your feedback! We ask that you take some tme and com- Tue., May 8th 6:00-7PM plete the School District of Philadelphia 2018 Parent & Guardian Survey now availa- ble through June 23rd. You will need your student’s ID number to access the survey, Kindergarten Open House ID numbers can be found on your child’s latest report card. Thur., May 10th 9:00-10AM Moving? Moving? Not returning to PAS next Fall? If you are Pretzel Friday ($1) planning to relocate, or not return to Penn Alexander Fri., May 11th next Fall, please contact the ofce with a writen leter as soon as possible. This informaton will assist Dinner & Bingo Night us in planning and reorganizing for the upcoming school-year. We have a number of students on our Fri., May 11th 5:30-8PM wait-list for each grade. Thanks for your communica- ton. Interim Reports (Grs. 5-8) Monday, May 14th Home and School Associaton (May 8th) Atenton 4th & 5th Grade Families– The May Home and School (HSA) meetng , on Tuesday, May 9th 6-7PM, will Electon Day, School Closed feature our 5th grade & Middle School teachers. -

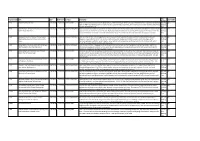

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

January at PENN 2015

Photo credit Eduardo Patino a nod to the diverse and oft-times ornate organizational letterheads of times gone MUSIC by; Penn Museum. Through February 14. 7 The Ghetto: Music for a Merchant; the Nikon Small World Exhibition; dis- Swiss-Italian ensemble Lucidarium per- cover the beauty and complexity of life as forms Venetian Jewish music of the February seen through advanced microscopes with Baroque era, evoking the sights and sounds the exhibit of winning images from of Shylock’s world – part of program on A T P E N N Nikon’s Small World photography contest; the Venetian Ghetto; 2:30 p.m.; Class of Wistar Institute. Through March 4. 1978 Pavilion, Van Pelt-Dietrich Library; Year of Health–Corn: From Ancient free and open to the public (Jewish Studies Crop to Soda Pop; corn as an important Program). See Talks. crop that has impacted human health; Wherever these symbols appear, more images or audio/video clips are Penn Museum. Through March 13. Annenberg Center available on our website, www.upenn.edu/almanac Children of Abraham by Abbas; Mag- Tickets: num Photos photographer Abbas; Arthur www.annenbergcenter.org Esther Klein Gallery: free; Ross Gallery. Through March 20. 19 Cyrille Aimée; fresh, creative ACADEMIC CALENDAR Mon.-Sat., 9 a.m.-5 p.m.; The Civil War: An Ephemeral Lens vocal approach that honors jazz Into the Life and Times; on the home Course Selection Period ends. http://estherkleingallery.tumblr.com/ tradition while blazing in intoxicating, 1 Goldstein Family Gallery, 6th floor, front and the front lines of the Union and new directions; 8 p.m.; Harold Prince 19 Drop Period ends. -

Class of 1969 – 50Th Reunion Then and Now Campus Tour 1

Class of 1969 – 50th Reunion Then and Now Campus Tour 1. Houston Hall - exit on Spruce St. Houston Hall was the country’s first student union martial arts and aerobics as well as a juice bar. Just like when you were at completed in 1896. It originally featured a 4 lane bowling alley, swimming pool, gym Penn! If you look west on Walnut Street, you can imagine Smokey Joe’s and locker room in the basement. A student lounge, billiards room and reception at 38th and Walnut. It is now on 40th St. If you look east, you can picture area were located on the first floor. An auditorium, athletic department and trophy Pagano’s. room were on the second floor and offices for student clubs including The Daily 10. Walk down Walnut to Penn Book Store and Hill Square. The Institute of Pennsylvanian were on the third floor. Houston Hall is still in use today with lower Contemporary Art (ICA) is at 118 S 36th St. The Penn Bookstore Building level food court and upper floor performance spaces, meeting rooms and offices for also contains The Inn at Penn, The Faculty Club and numerous shops student organizations. and restaurants. The bookstore itself is a combination of a full service 2. Claudia Cohen Hall formerly Logan Hall opened for use as the Medical School in 1874. academic bookstore and a Barnes and Noble. The computer connection When the Medical School moved to Hamilton Walk, Logan Hall became home to the is housed in the bookstore. As we walk down Walnut, remember the Wharton School. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 07:16 16 August 2016 Kahn at Penn](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8191/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-07-16-16-august-2016-kahn-at-penn-1248191.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 07:16 16 August 2016 Kahn at Penn

Downloaded by [New York University] at 07:16 16 August 2016 Kahn at Penn Louis I. Kahn is widely known as an architect of powerful buildings. But although much has been said about his buildings, almost nothing has been written about Kahn as an unconventional teacher and philosopher whose influence on his students was far-reaching. Teaching was vitally important for Kahn, and through his Master’s Class at the University of Pennsylvania, he exerted a significant effect on the future course of architectural practice and education. This book is a critical, in-depth study of Kahn’s philosophy of education and his unique pedagogy. It is the first extensive and comprehensive investi- gation of the Kahn Master’s Class as seen through the eyes of his graduate students at Penn. James F. Williamson is a Professor of Architecture at the University of Memphis and has also taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, Drexel University, and Rhodes College. He holds two Master of Architecture degrees from Penn, where he was a student in Louis Kahn’s Master’s Class of 1974. He was later an Associate with Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates. For over thirty years he practiced as a principal in his own firm in Memphis with special interests in religious and institutional architecture. Williamson was elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in recognition of his contributions in architectural design and education. He is the recipient of the 2014 AIA Edward S. Frey Award for career contribu- tions to religious architecture and support of the allied arts.