05 Østern EDIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download the Mccoy Tyner Collection

THE MCCOY TYNER COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK McCoy Tyner | 120 pages | 01 Nov 1992 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9780793507474 | English | Milwaukee, United States The Mccoy Tyner Collection PDF Book Similar Artists See All. There's magic in the air, or at the very least a common ground of shared values that makes this combination of two great musicians turn everything golden. That's not to say their progressive ideas are completely harnessed, but this recording is something lovers of dinner music or late-night romantic trysts will equally appreciate. McCoy Tyner. Extensions - McCoy Tyner. Tyner died on March 6, at his home in New Jersey. They sound empathetic, as if they've played many times before, yet there are enough sparks to signal that they're still unsure of what the other will play. Very highly recommended. Albums Live Albums Compilations. Cart 0. If I Were a Bell. On this excellent set, McCoy Tyner had the opportunity for the first time to head a larger group. McCoy later said, Bud and Richie Powell moved into my neighborhood. He also befriended saxophonist John Coltrane, then a member of trumpeter Miles Davis' band. A flow of adventurous, eclectic albums followed throughout the decade, many featuring his quartet with saxophonist Azar Lawrence, including 's Song for My Lady, 's Enlightenment, and 's Atlantis. McCoy Tyner Trio. See the album. Throughout his career, Tyner continued to push himself, arranging for his big band and releasing Grammy-winning albums with 's Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane and 's The Turning Point. However, after six months with the Jazztet, he left to join Coltrane's soon-to-be classic quartet with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. -

Abstract.Pdf

52701311 : สาขาสังคีตวิจัยและพัฒนา คําสําคัญ : เปียโน / แมคคอย ไทเนอร์ รัตนะ วงศ์สรรเสริญ : แบบฝึกหัดการเล่นเปียโนกรณีศึกษาเพลง Passion Dance ของแมคคอย ไทเนอร์. อาจารย์ทีปรึกษาวิทยานิพนธ์ : อ.ดร.ยศ วณีสอน. 168 หน้า แมคคอย ไทเนอร์ เป็นนักเปียโนแจ๊สทีมีอิทธิพลต่อวงการดนตรีแจ๊สเป็นอย่างมาก เขา ได้เป็นมือเปียโนทีร่วมเล่นกับ เบนนี โกลสัน (Benny Golson) ตังแต่อายุ 17 ปี จนกระทังในปี ค.ศ. 1960 แมคคอย ไทเนอร์ ได้ร่วมเล่นและบันทึกเสียงกับนักแซกโซโฟนระดับแนวหน้าของโลก คือ จอห์น โคลเทรนซึงทําให้แมคคอยห อไทเนอร์สม ได้เป็นทียอมรับในฝีมือและเป็นทีรู้จักในแวดวงุดกล ดนตรีแจ๊สทัวโลก แม็คคอยำน ไทเนอร์ยังได้รับรางวัลมากมายซึงเป็นทียอมรับทัวโลกกั าง เช่น อัลบัม ส เพลงบรรเลงแจ๊สยอดเยียม จากแกรมมี อวอร์ด (Grammy Award) ในปี 2004 และสไตเวแอ่นซัน อาร์ติสต์ (Stienway & Sons Artist)ตังแต่ปี 1977 ฯลฯ ในผลงานวิจัยชินนี ผู้วิจัยได้ศึกษาวิเคราะห์ การใช้เสียงประสานและการใช้ทํานองในการด้น(Improvisation) รวมถึงรูปแบบ วิธีการเล่นและ เทคนิคของแม็คคอย ไทเนอร์ในเพลง Passion Dance และ You Stepped Out of A Dream จากนันนําผลการวิเคราะห์ มาสังเคราะห์เป็นแบบฝึกหัดใหม่ในสไตล์ของแมคคอย ไทเนอร์ โดย แบ่งการวิเคราะห์ และสังเคราะห์เป็น 4 หมวดหมู่ดังนี 1)การใช้บันไดเสียงและโหมด 2)การใช้ ทรัยแอดและอาร์เปจจิโอ 3)การใช้เสียงประสานแบบคู่สีและคู่ห้า 4)การใช้บันไดเสียงเพนทาโทนิก . สาขาวิชาสังคีตวิจัยและพัฒนา บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ลายมือชือนักศึกษา....................................... ปีการศึกษา 2555 ลายมือชืออาจารย์ทีปรึกษาวิทยานิพนธ์ .………………………… ง 52701311 : MAJOR : MUSIC RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT KEY wORD : PIANO / MCCOY TYNER RATTANA wONGSANSERN : JAZZ PIANO ETUDES BASE ON -

Danceafrica 2017 Illstyle & Peace Productions

BAM 2017 Winter/Spring Season #DanceAfrica Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President DanceAfrica Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 2 017 The Healing Light of Rhythm: Tradition and Beyond Artistic Director Abdel R. Salaam and Artistic Director Emeritus Chuck Davis BAM Howard Gilman Opera House May 26 at 7:30pm; May 27 at 2pm & 7pm; May 28 & 29 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 15 minutes, including one intermission Produced by BAM Season Sponsor: Asase Yaa Forces of Nature Dance Theatre Time Warner Inc. is the 2017 DanceAfrica Sponsor. Illstyle & Peace Productions Wula Drum and Dance Ensemble Support for Muslim Stories: Global to Local provided by the Building Bridges Program of the Doris Duke BAM/Restoration Dance Youth Ensemble Foundation for Islamic Art. Lighting design by Al Crawford Zipcar is the DanceAfrica Car-Sharing Sponsor. Sound design by David Margolin Lawson Forest City Ratner Companies is the Presenting Costume design by Hopie Lyn Burrows Sponsor of Dance Education. Stage manager N’Goma Woolbright Leadership support for dance at BAM provided Assistant stage manager Normadien Woolbright by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Major support for dance at BAM provided by The SHS Foundation. Support for the Signature Artist Series provided by Howard Gilman Foundation. DanceAfrica 2017 Illstyle & Peace Productions. Photo by Darrina Ross Productions. Illstyle & Peace Peace and blessings! Welcome to the 40th Anniversary of BAM’s DanceAfrica Festival! This year is a milestone in American history celebrating the dance, music, and culture of the African diaspora here at home and abroad. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

Geographic Perspectives on Contemporary / Smooth Jazz

GEOGRAPHIC PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY / SMOOTH JAZZ By WILLIAM ROBERT FLYNN Bachelor of Music in Classical Guitar Performance California State University, Fullerton Fullerton, California 2000 Master of Applied Geography Texas State University San Marcos, Texas 2001 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 GEOGRAPHIC PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY / SMOOTH JAZZ Dissertation Approved: Dr. G. Allen Finchum Dissertation Adviser Dr. Brad A. Bays Dr. Jonathan C. Comer Dr. Thomas Lanners Outside Committee Member ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing this dissertation and my doctoral program at Oklahoma State University would not have been possible without the support of many people over the past ten years. I would like to start with my advisor and chair, Dr. Allen Finchum, who not only happens to share my interest in smooth jazz, but has always been there for me. One could not ask for a better mentor, as he was always so giving of his time, whether we were discussing my research, talking about my experiences as a graduate instructor, or him just taking an interest in my personal life. I feel blessed to have been able to work with such a special graduate committee, comprised of Dr. Jon Comer, Dr. Brad Bays, and Dr. Tom Lanners. Dr. Comer sparked my passion for quantitative methods and spatial analysis, and Dr. Bays taught my very first course at OSU, a wonderful and stimulating seminar in historical geography. With Dr. Lanners, I could not have asked for a better fit for my outside committee member, and I feel privileged to have been able to work with a musician of his caliber. -

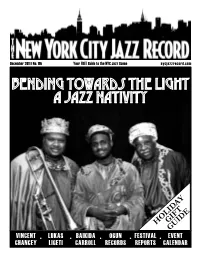

Bending Towards the Light a Jazz Nativity

December 2011 | No. 116 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com bending towards the light a jazz nativity HOLIDAYGIFT GUIDE VINCENT •••••LUKAS BAIKIDA OGUN FESTIVAL EVENT CHANCEY LIGETI CARROLL RECORDS REPORTS CALENDAR The Holiday Season is kind of like a mugger in a dark alley: no one sees it coming and everyone usually ends up disoriented and poorer after the experience is over. 4 New York@Night But it doesn’t have to be all stale fruit cake and transit nightmares. The holidays should be a time of reflection with those you love. And what do you love more Interview: Vincent Chancey than jazz? We can’t think of a single thing...well, maybe your grandmother. But 6 by Anders Griffen bundle her up in some thick scarves and snowproof boots and take her out to see some jazz this month. Artist Feature: Lukas Ligeti As we battle trying to figure out exactly what season it is (Indian Summer? 7 by Gordon Marshall Nuclear Winter? Fall Can Really Hang You Up The Most?) with snowstorms then balmy days, what is not in question is the holiday gift basket of jazz available in On The Cover: A Jazz Nativity our fine metropolis. Celebrating its 26th anniversary is Bending Towards The 9 by Marcia Hillman Light: A Jazz Nativity (On The Cover), a retelling of the biblical story starring jazz musicians like this year’s Three Kings - Houston Person, Maurice Chestnut and Encore: Lest We Forget: Wycliffe Gordon (pictured on our cover) - in a setting good for the whole family. -

African Dancing and Drumming in the Little Village of Tallahassee, Florida Andrea-Latoya Davis-Craig

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Building Community: African Dancing and Drumming in the Little Village of Tallahassee, Florida Andrea-Latoya Davis-Craig Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATER, AND DANCE BUILDING COMMUNITY: AFRICAN DANCING AND DRUMMING IN THE LITTLE VILLAGE OF TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA By ANDREA-LA TOYA DAVIS-CRAIG A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Andrea-La Toya Davis-Craig All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Andrea-La Toya Davis-Craig defended on 03-19-2009. ____________________________________ Pat Villeneuve Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patricia Young Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Committee Member ____________________________________ Tom Anderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________ David Gussak, Chair, Department of Art Education The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I am because you are. Dedicated to: My grandmother Aline Mickens Not a day goes by that I don’t think of you. I love you grandma. My grandmother Lottie Davis I never met you, but I know my dad and know that he is a reflection of you. My parents Lt. Col. Walter and Andrea Davis Your unyielding support, sacrifice, and example have taught me anything is possible. & My ancestors You fought the fight so that I could walk in the light. -

Learn About the Hit TV Show Dance Moms! $3.99

Learn about the hit TV show Dance Moms! How much does it cost to be a dancer? $3.99 Dear Reader, process, I got some writers who were willing I hope you have enjoyed the past issues of to write for me. This being a dance Dancer’s Corner as much as I have. I wrote magazine, finding writers was a difficult this magazine to show people what it takes task. Many people did not feel comfortable to be a dancer, and to have fun with dance. with writing about dance. Some writers When I initially started this thinking backed out when I needed them most, but process, I intended the magazine to be just others came through. I was becoming for dancers. Whether it was competition, stressed about putting the magazine recreational, or independent. It turned out together, but it worked in the end. to become a guide for dancers and for future I got to work with some amazing dancers. To help the parents as much as the writers while creating this magazine. These kids, and to support your passion. I look at writers were dedicated and even if they other dance magazines and they are all didn’t know all that much about dance, they focused on the big dancers. While they came through to write for me. An article write about others people’s that stood out to me was written by someone accomplishments, you are trying to achieve who does not dance, but was willing to help your own goals. That’s what sets Dancer’s me. -

Sommaire Catalogue Jazz / Blues Octobre 2011

SOMMAIRE CATALOGUE JAZZ / BLUES OCTOBRE 2011 Page COMPACT DISCS Blues .................................................................................. 01 Multi Interprètes Blues ....................................................... 08 Jazz ................................................................................... 10 Multi Interprètes Jazz ......................................................... 105 SUPPORTS VINYLES Jazz .................................................................................... 112 DVD Jazz .................................................................................... 114 L'astérisque * indique les Disques, DVD, CD audio, à paraître à partir de la parution de ce bon de commande, sous réserve des autorisations légales et contractuelles. Certains produits existant dans ce listing peuvent être supprimés en cours d'année, quel qu'en soit le motif. Ces articles apparaîtront de ce fait comme "supprimés" sur nos documents de livraison. BLUES 1 B B KING B B KING (Suite) Live Sweet Little Angel – 1954-1957 Selected Singles 18/02/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN (SAGAJAZZ) (900)CD 18/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GACFBH=YYZZ\Y: #:GAAHFD=VUU]U[: Live At The BBC 19/05/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / EMARCY The birth of a king 10.CLASS.REP(SAGAJAZZ) (899)CD 23/08/2004 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GAAHFD=U[XVY^: #:GACEJI=WU\]V^: One Kind Favor 25/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN Live At The Apollo(ORIGINALS (JAZZ)) (268)CD 28/04/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GRP (899)CD #:GACFBH=]VWYVX: -

May 2011 Vol

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community May 2011 Vol. 27, No. 5 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Chuck Deardorf Photo by Daniel Sheehan LETTER FROM THE NOTES DIRECTOR Aiko Shimada and Burnlist Ernestine Anderson and Carver Dear Jazz Fan, Headline Japan Benefit on May 14 Gayton Honored by Northwest With this May issue, we celebrate Presented by the Japan Young Pro- African American Museum Seattle jazz with a profile of recent fessionals Group (JYPG) and Ear- A Night at the Museum is the North- Seattle Jazz Hall of Fame inductee shot Jazz, vocalist Aiko Shimada and west African American Museum’s Chuck Deardorf and the bassist’s the group Burnlist (Cuong Vu, Greg (NAAM) first annual gala fundrais- abundant contributions to the Sinibaldi, Chris Icasiano, and Aaron ing event, set for Saturday May 14 at quality of the Seattle jazz scene as Otheim) headline a special concert ben- 6pm at the museum (2300 S. Massa- an educator, mentor, and example efiting Japan earthquake relief through chusetts). The event honors two major of excellence on the bandstand. As the Peace Winds America agency. The contributors to the Pacific Northwest always, this Earshot Jazz publica- concert takes place on May 14 at 7pm African American community: Dr. tion includes news for the com- at the clubhouse of Seattle’s Nisei Vet- Carver C. Gayton, NAAM’s Found- munity as well as a comprehensive erans Committee (1212 S. King Street, ing Director, and Ernestine Anderson, calendar of jazz events all around Seattle). JYPG works closely with the Grammy Award-winning jazz vocal- the region, in this case, extending Japan America Society of the State of ist. -

Mccoy Tyner, Austin Peralta, and Modal Jazz

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................... 2 Review of Literature ..................................................................................................... 4 Research Methodology ................................................................................................ 6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 2: Modal Jazz: From Davis to Peralta .................................................................... 8 The Origins of Modal Jazz ............................................................................................ 8 John Coltrane and Modal Jazz .................................................................................... 12 McCoy Tyner and Modal Jazz ..................................................................................... 14 Austin Peralta and Modal Jazz ................................................................................... 15 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 17 Chapter 3: McCoy Tyner’s Improvisational Style ............................................................. 18 McCoy Tyner and “Passion Dance” ............................................................................ 18 Melodic Material ....................................................................................................... -

Milestone Records Discography

Milestone Label Discography Milestone Records was established in New York City in 1966 by Orrin Keepnews and Dick Katz. The label recorded mostly jazz with a small amount of blues. The label was made part of Fantasy Records in 1972. Since that time it has been used as a reissue label in addition to new jazz recordings. Milestone has also reissued many historic jazz recordings, including the Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings recordings that were originally made in the 1920’s by Richmond Indiana label Gennett Records. This discography was compiled using Schwann catalogs from 1966 to 1982 and information from the Michael Fitzgerald website. www.JazzDiscography.com 2000 Series: MLP 2001 - The Immortal Ma Rainey - Ma Rainey [1966] Jealous Hearted Blues/Cell Bound Blues/Army Camp Harmony Blues/Explainin' The Blues/Night Time Blues/'Fore Day Honry Scat///Rough And Tumble Blues/Memphis Bound Blues/Slave To The Blues/Bessemer Bound Blues/Slow Driving Moan/Gone Daddy Blues MLP 2002 - The Immortal Johnny Dodds - Johnny Dodds [1967] Rampart Street Blues/Don't Shake It No More/Too Sweet For Words/Jackass Blues/Frog Tongue Stomp/C.C. Pill Blues//Oriental Man/Steal Away/Oh Daddy/Lonesome Blues/Long Distance Blues/Messin' Around No. 2 MLP 2003 - The Immortal Jelly Roll Morton - Jelly Roll Morton [1967] Froggy Moore/35th Street Blues/Mamanita/London Blues/Wolverine Blues/My Gal/ /Big Fat Ham/Muddy Water Blues/Mr. Jelly Lord/Fish Tail Blues MLP 2004 - The Immortal Blind Lemon Jefferson - Blind Lemon Jefferson [1967] Lemon's