Bank Management Response To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experiences, Challenges and Lessons Learnt in Papua New Guinea

Practice BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003747 on 3 December 2020. Downloaded from Mortality surveillance and verbal autopsy strategies: experiences, challenges and lessons learnt in Papua New Guinea 1 1 2 3 4 John D Hart , Viola Kwa, Paison Dakulala, Paulus Ripa, Dale Frank, 5 6 7 1 Theresa Lei, Ninkama Moiya, William Lagani, Tim Adair , Deirdre McLaughlin,1 Ian D Riley,1 Alan D Lopez1 To cite: Hart JD, Kwa V, ABSTRACT Summary box Dakulala P, et al. Mortality Full notification of deaths and compilation of good quality surveillance and verbal cause of death data are core, sequential and essential ► Mortality surveillance as part of government pro- autopsy strategies: components of a functional civil registration and vital experiences, challenges and grammes has been successfully introduced in three statistics (CRVS) system. In collaboration with the lessons learnt in Papua New provinces in Papua New Guinea: (Milne Bay, West Government of Papua New Guinea (PNG), trial mortality Guinea. BMJ Global Health New Britain and Western Highlands). surveillance activities were established at sites in Alotau 2020;5:e003747. doi:10.1136/ ► Successful notification and verbal autopsy (VA) District in Milne Bay Province, Tambul- Nebilyer District in bmjgh-2020-003747 strategies require planning at the local level and Western Highlands Province and Talasea District in West selection of appropriate notification agents and VA New Britain Province. Handling editor Soumitra S interviewers, in particular that they have positions of Provincial Health Authorities trialled strategies to improve Bhuyan trust in the community. completeness of death notification and implement an Additional material is ► It is essential that notification and VA data collec- ► automated verbal autopsy methodology, including use of published online only. -

New Britain New Ireland Mission, South Pacific Division

Administrative Office, New Britain New Ireland Mission, Kokopo, 2012. Built after volcanic eruption in Rabaul. Photo courtesy of Barry Oliver. New Britain New Ireland Mission, South Pacific Division BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The New Britain New Ireland Mission (NBNI) is the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) administrative entity for a large part of the New Guinea Islands region in Papua New Guinea located in the South West Pacific Ocean.1 The territory of New Britain New Ireland Mission is East New Britain, West New Britain, and New Ireland Provinces of Papua New Guinea.2 It is a part of and responsible to the Papua New Guinea Union Lae, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. The Papua New Guinea Union Mission comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the country of Papua New Guinea. There are nine local missions and one local conference in the union. They are the Central Papuan Conference, the Bougainville Mission, the New Britain New Ireland Mission, the Northern and Milne Bay Mission, Morobe Mission, Madang Manus Mission, Sepik Mission, Eastern Highlands Simbu Mission, Western Highlands Mission, and South West Papuan Mission. The administrative office of NBNI is located at Butuwin Street, Kokopo 613, East New Britain, Papua New Guinea. -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

Kokoda Track Pre-Departure Information Guide

KOKODA TRACK AUTHORITY A Special Purposes Authority of the Kokoda and Kolari Local-level Governments Kokoda Track Pre-Departure Information Guide May 2013 July 2013 Disclaimer of Liability: The information provided in this pre-departure information guide is general advice only. The Kokoda Track Authority accepts no liability for any injury or loss sustained by trekkers, guides or porters on the Kokoda Track. Trekkers considering undertaking the Kokoda Track should contact their licensed tour operator and discuss all information with them. 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 3 1.1 HISTORY OF THE KOKODA TRACK ................................................................ 3 1.2 THE KOKODA TRACK TODAY ........................................................................ 3 1.3 TREKKING ON THE KOKODA TRACK ............................................................. 4 1.4 RESPECT THE CULTURE: RESPECT THE LAND .............................................. 4 1.5 CHOOSING A TOUR OPERATOR ................................................................... 5 2. CLIMATE AND TERRAIN ..................................................................... 7 2.1 CLIMATE ....................................................................................................... 7 2.2 GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES OF THE KOKODA TRACK ................................... 8 3. PREPARING FOR YOUR WALK ............................................................ 9 3.1 FITNESS AND ENDURANCE .......................................................................... -

OWEN STANLEY CAMPAIGN KOKODA to IMIT a ATE in June

CHAPTER 2 OWEN STANLEY CAMPAIGN KOKODA TO IMIT A ATE in June Major-General Morris, commander of New Guinea Force , L assigned to the Papuan Infantry Battalion and the 39th Australia n Infantry Battalion the task of preventing any movement of the Japanes e across the Owen Stanley Range through the Kokoda Gap. The Japanese had not yet landed in Papua, but for months their aircraft had bee n regularly bombing Port Moresby . Early in July General MacArthur ordered the assembly of a force of some 3,200 men to construct and defend an airfield in the Buna area. It was to begin operations early the following month. Kokoda was easily accessible from the north coast of Papua by track s which led gradually up to an elevation of a mere 1,500 feet, where ther e was a most useful airstrip. From the Moresby end, however, the line o f communication by land route ran over the arduous Kokoda Trail, rising and falling steeply and incessantly over a range whose highest peak rose to 13,000 feet, and to cross which a climb of 7,000 feet was necessary . THE KOKODA TRAIL This trail was in reality a native road, no doubt of ancient origin, an d followed the primitive idea of dropping into deep valleys only to clamber up forbidding heights, instead of the more modern notions of surveyin g in terms of levels . Even the road from Moresby to Koitaki, some twenty - five miles from the port, was not really practicable for motor traffic until engineers blasted a wider path, and the journey from the upper reaches of the Laloki River to Ilolo, always difficult, became impossible after heavy rain. -

Department of Environment and Conservation

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION KOKODA INITIATIVE – STREAM B2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESKTOP STUDY 21 December 2012 A report by ANU Enterprise Pty Ltd Building 95, Fulton Muir Building Corner Barry Drive & North Road The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia ACN 008 548 650 Pictures (M. Leavesley and M. Prebble) of Madilogo archaeological survey 2012 in clockwise order: A. sieving sediment (Rex, Jonah, Gilbert and Elton); B. Mrs Kabi Moea with stone axe; C. Mrs Deduri with stone axe D. Herman Mandui (NMAG) drawing stone axe. AUTHORS Dr Matthew Leavesley Convener of Archaeology and Deputy Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Dr Matthew Prebble Research Fellow, Archaeology & Natural History, School of Culture History and Languages, College of Asia & Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia 18 December 2012 A report by ANU Enterprise Pty Ltd for Department of Environment and Conservation (Papua New Guinea Government, Port Moresby) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report was commissioned by the the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC, Papua New Guinea) as part of work under the Joint Understanding between the Australian and Papua New Guinea governments. The report is a Desktop Study, with inputs from preliminary consultations and fact-finding in Port Moresby, namely at the National Museum and Art Gallery, Papua New Guinea and University of Papua New Guinea Library, but also at the National Library, National Archives and Australian National University Libraries in Canberra, Australia. This report also outlines the utility of aerial imagery from early surveys obtained since 1956 as a tool for archaeological interpretation within the AOI. -

51035-001: Health Services Sector Development Program

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report July 2020 PNG: Health Services Sector Development Program Subproject: Bitokara Community Health Post Prepared by the Department of Health for the Asian Development Bank. This social safeguards due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Social Safeguards & Land Assessment Report Bitokara Community Health Post West New Britain Provincial Health Authority Health Services Sector Development Project National Department of Health 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 17 June 2020) Currency unit – Kina (K) K1.00 = $0.29 $1.00 = K3.46 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – Affected Persons CCHS – Catholic Church Health Services CEO – Chief Executive Officer CHP – Community Health Post (a level 2 health facility in NHSS) DDA – District Development Authority DDR – Due Diligence Report DHM – District Health Manager DH – District Hospital GRC – Grievance Redress Committee GRM – Grievance Redress Mechanism GoPNG – Government of PNG ha – Hectare HC – Health Centre HSSDP – Health Services Sector Development Project IPPF – Indigenous Persons Planning Framework LARF -

Papua New Guinea’S

Papua New Guinea’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity December 2017 Papua New Guinea’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity Table of Contents Page Executive Summary 1 Part I Biodiversity Status, Trends and Threats and Implications for Human Well-being 16 1. Biodiversity importance in PNG 16 1.1 Human well-being 16 1.2 Socio-economic development 17 1.3 Biodiversity and ecosystems of PNG 19 1.3.1 Terrestrial biodiversity 20 1.3.2 Marine biodiversity 27 2. Major changes in the status and trends of Biodiversity in PNG 28 2.1 Biodiversity status 28 2.1.1 Protected Areas status 31 2.1.2 Species status 32 2.2 Biodiversity trends 34 2.2.1 Trends in Terrestrial biodiversity 34 2.2.2 Trends in Marine biodiversity 39 2.3 Case studies 40 2.3.1 Tree Kangaroo Conservation Program 40 2.3.2 Tenkile Conservation Program 43 2.3.3 Netuli Locally Managed Marine Area 46 2.3.4 Sustainable Wildlife Trade-CITES-Crocodile skin Trade 47 2.3.5 Sustainable Wildlife trade-CITES-Insect trade 48 2.3.6 Beche-de-mer trade 49 2.3.7 Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) 50 3. Main threats to Biodiversity in PNG 54 3.1 Landuse change 54 3.1.1 Commercial logging 55 3.1.2 Subsistence agriculture 55 3.1.3 Commercial agriculture 56 3.1.4 Mining 57 3.1.5 Fire 60 3.2 Climate change 61 3.2.1 Terrestrial ecosystems 61 3.2.2 Marine ecosystems 62 3.2.3 Coastal ecosystems 63 3.3 Direct Exploitation 64 3.3.1 Overfishing 65 3.3.2 Firewood 66 3.3.3 Subsistence hunting 67 3.3.4 Non-wood forest products 70 3.4 Eutrophication 70 3.5 Ocean Acidification 72 3.6 Invasive species 72 3.7 Roads 76 3.8 Over-exploitation 76 3.9 Destructive fishing 77 2 Papua New Guinea’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity 3.10 Climate change in a marine environment 78 3.11 Pollution 80 3.12 Extractive industries 81 3.13 Development corridors 83 3.14 Illegal export/Trade 86 3.15 Other Underlying drivers of biodiversity change 87 4. -

Divune Hydropower Plant Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 41504 August 2010

Indigenous Peoples Assessment and Measures Indigenous Peoples Plan: Divune Hydropower Plant Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 41504 August 2010 Papua New Guinea: Town Electrification Project Prepared by PNG Power Ltd for Asian Development Bank The Indigenous Peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected people/persons CDO – Community Development Officer DPE – Department of Petroleum and Energy DLO – District Lands Officer EA – Executing Agency HA – hectare HH – households IA – Implementing Agency IPP – Indigenous Peoples Plan LLG – Local Level Government MW _ megawatt MOA – memorandum of agreement MFF – Multi-Tranche Financing Facility M – meter PLO – Provincial Lands Officer PMU – Project Management Unit PNG – Papua New Guinea PPL – PNG Power Ltd RP – resettlement plan TEP – Town Electrification Project CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 II. BACKGROUND/PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2 III. OBJECTIVE AND POLICY FRAMEWORK 2 IV. SOCIAL ANALYSIS 3 A. General Demographic and Social Information of the Subproject Area 3 B. Profile of the Directly Affected People 7 C. Assessment of Impact on Customary Landowners 8 V. INFORMATION DISCLOSURE, CONSULTATION AND PARTICIPATION 9 VI. GRIEVANCE REDRESS MECHANISM 11 VII. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT BENEFITS FOR AFFECTED COMMUNITIES 11 A. Free Power Connection 12 B. Access to Energy-Efficient Bulbs 12 C. Village Water Supply 12 D. Awareness and Skills Training 12 VIII. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING 13 IX. BUDGET AND FINANCING 13 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The Divune subproject under Tranche 1 project of the Town Electrification Investment Program (TEIP) includes: (i) building a hydropower plant (3 MW) in Divune River, Oro Province; and (ii) extending transmission lines to Kokoda and Popondetta Town. -

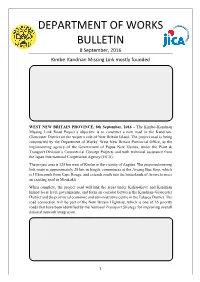

Kimbe Kandrian Missing Link Underway

DEPARTMENT OF WORKS BULLETIN 8 September, 2016 Kimbe‒Kandrian Missing Link mostly founded WEST NEW BRITAIN PROVINCE, 8th September, 2016 – The Kimbe–Kandrian Missing Link Road Project’s objective is to construct a new road in the Kandrian- Gloucester District on the western side of New Britain Island. The project road is being constructed by the Department of Works’ West New Britain Provincial Office, as the implementing agency of the Government of Papua New Guinea, under the Plant & Transport Division’s Commercial Concept Projects and with technical assistance from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The project area is 125 km west of Kimbe in the vicinity of Augitni. The proposed missing link route is approximately 20 km in length, commences at the Aiyang Bus Stop, which is 15 km south from Cape Rouge, and extends south into the hinterlands of Arowe to meet an existing road in Moukukli. When complete, the project road will link the areas under Kaliai-Kove and Kandrian Inland local level governments, and form an corridor between the Kandrian-Gloucester District and the provincial economic and administrative centre in the Talasea District. The road connection will be part of the New Britain Highway, which is one of 16 priority roads that have been identified by the National Transport Strategy for improving overall national network integration. 1 The proposed scope of the work is as follows: Clearing and grubbing of existing 15-km section from Cape Rouge to Complete Aiyang Bus Stop Clearing, grubbing and stripping of top soil in the 20-km missing link section Underway Construction of log bridges over streams Construction of subgrade formation Excavation of all material to construct the road Pending Construction and compaction of subbase layer The work commenced on 22nd June, 2016, shortly after the heavy equipment landed at Cape Rouge and has been progressing at a rate of 3.5 km to 4 km per month. -

'Track' Or 'Trail'? the Kokoda Debate1

‘Track’ or ‘Trail’? The Kokoda Debate1 Peter Provis Introduction The debate as to what should be the name of the route over the Owen Stanley Ranges, Kokoda ‘Track’ or ‘Trail’, has been persistent and spirited, despite appearing on the surface to be a minor issue of semantics. The topic has often resulted in the bitter exchange of correspondence between passionate interested parties who fervently advocate either ‘track’ or ‘trail’, offering a variety of evidence in support of what they believe to be the correct title of one of Australia’s most important and revered military campaigns. This article examines the use of the terms ‘track’ and ‘trail’ during the campaign and their use since in a variety of sources. The research was undertaken to provide an in‐depth response to the innumerable inquiries the Australian War Memorial receives regarding the matter.2 To determine the terms used at the time of the campaign, a wide range of material has been examined, including the war diaries of units that served in the Owen Stanley Ranges in 1942; official reports and a number of private records, especially diaries kept by servicemen, have been included. This has determined whether both versions were used at the time and how frequently they appear in the records. It has been asserted that the term ‘trail’ was coined by war correspondents covering the campaign. I will examine the legitimacy of these claims and 1 This article has been peer reviewed. 2 The author held a Summer Research Scholarship at the Australian War Memorial in 2003. fjhp | volume 26, 2010 | page 127 which terms were used in the newspapers covering the campaign. -

Support for the Establishment of Effectively Managed Platform Sites As Foundations for Resilient Networks of Functionally-Connected Marine Protected Areas

Support for the Establishment of Effectively Managed Platform Sites as Foundations for Resilient Networks of Functionally-Connected Marine Protected Areas Kimbe Bay, West New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea FY06 Annual Report This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of Award No. LAG-A-00-99-00045-00. The contents are the responsibility of The Nature Conservancy and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. TABLE OF ACTIVITY STATUS Activity Activity Title Status Page number Number Support for the Establishment of Effectively Managed Platform Sites as Foundations for Resilient Networks of Functionally-Connected Marine Protected Areas Kimbe Bay, West New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea Objective Increase understanding of the importance of marine ecosystems and ensure 1 long term support for their conservation by local communities and other stakeholders in Kimbe Bay. 1.1 Build community awareness and promote Mixed marine conservation approaches among Performance interested communities. 1.2 Increase Provincial and Local Level Government support for conservation at On Track Kimbe Bay. 1.3 Initiate consultations with key national government agencies and local industries to On Track gain support for marine biodiversity conservation at Kimbe Bay 1.4 Develop communications strategy and materials to support stakeholder On Track engagement and partnership development. 1.5 Identify potential partners and conservation Delayed, but now “champions” among graduates of high Underway school marine education program. Objective 2 Design and implement a functionally-connected network of LMMAs and MPAs in Kimbe Bay.