Psalm 5: a Theology of Tension and Reconciliationl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proverbs for Teens

Proverbs for Teens By Jodi Green All scripture quotations are from The Believer’s Study Bible: New King James Version. 1991. Thomas Nelson, Inc. edited by W.A. Criswell Proverbs for Teens Copyright 2012 by Jodi Green INTRODUCTION When I was in junior high school (middle school now days), I heard about Billy Graham’s practice of reading five chapters of Psalms and one chapter of Proverbs every day. Since there are 150 chapters of Psalms and 31 chapters of Proverbs, that meant he read the entire books of Psalms and Proverbs every month. And since Psalms teaches us to relate to God, and Proverbs teaches us to relate to our culture, Billy Graham’s idea seemed like a great one. Dr. Graham’s practice was to read the chapters of Proverbs according to the day of the month. For example, on the first day of the month he read Proverbs 1; the second day would be Proverbs 2, and so on. He read Psalms in order of the chapters, but we will discuss that more in the conclusion. My hope for this book is to begin training you to read a chapter of Proverbs every day. Proverbs is a book of wisdom, and we all need a daily dose of Biblical wisdom. Reading only one verse of scripture per day is like eating one spoonful of cereal for breakfast. It is still good for you, but you need a whole bowl to be nourished physically. In the same way, one verse of scripture is good for you, but you need more if you are to grow spiritually. -

Old Testament: Gospel Doctrine Teacher\222S Manual

“Let Every Thing That Hath Lesson Breath Praise the Lord ” 25 Psalms Purpose To help class members show their gratitude for the Savior and for the many blessings that he and our Heavenly Father have given us. Preparation 1. Prayerfully study the scriptures discussed in the lesson and as much of the book of Psalms as you can. 2. Study the lesson and prayerfully select the scriptures, themes, and questions that best meet class members ’ needs. This lesson does not cover the entire book of Psalms. Rather, it deals with a few of the important themes that are expressed throughout the book. 3. If you use the first attention activity, bring a picture of the Savior and four or five items that represent things for which you are grateful, such as the scrip- tures, a picture of a loved one, an item that represents one of your talents, or an item of food. If you use the second attention activity, ask one or two class members to prepare to share a favorite psalm and tell why it is important to them. 4. Bring one or more pictures of temples. Suggested Lesson Development Attention Activity You may want to use one of the following activities (or one of your own) as class begins. Select the activity that would be most appropriate for the class. 1. Show a picture of the Savior and express your gratitude for his life and mission. Display the items that represent other things for which you are grateful. Express your gratitude for each one. Then ask the following questions: • What gifts and opportunities from the Lord are you especially grateful for? How would your life be different without these blessings? Explain that many of the psalms express gratitude for blessings the Lord has given. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms for the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms For the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel Today we start a new series in the Psalms. The Psalms provide a wonderful resource of Praying the Psalms inspiration and instruction for prayer and worship of God. Ezra collected the Psalms which were written over a millennium by a number of authors including David, Asaph, Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan and Moses. The Psalms are organized into 5 collections (1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, and 107-150). As we read the book of Psalms we see a variety of psalms including praise, lament, messianic, pilgrim, alphabetical, wisdom, and imprecatory prayers. The Psalms help us see the importance of God’s Word (Torah) and the hopeful expectation of God’s people for Messiah (Jesus). • Why is the “law of the Lord” such an important concept in Psalm 1 for bearing fruit as a follower of Jesus? • In John 15, Jesus says that apart from Him you can do nothing. Compare the message of Psalm 1 to Jesus’ words in John 15. Where are they similar? • Psalm 2 tells of kings who think they have influence and yet God laughs at them (v. 3). Why is it important that we seek our refuge in Jesus (2:12)? • Our heart for Bethel Church in this season is that we would saturate ourselves with God’s Word, specifically the book of Psalms. We’ve created a reading plan that allows you to read a Psalm a day or several Psalms per day as well as a Proverb. -

The Imprecatory Psalms KJV 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, 137, 140 Psalm 5 1 Give Ear to My Words, O LORD

The Imprecatory Psalms KJV 7 His mouth is full of cursing and deceit and 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, fraud: under his tongue is mischief and vanity. 137, 140 8 He sitteth in the lurking places of the villages: in the secret places doth he murder the innocent: Psalm 5 his eyes are privily set against the poor. 1 9 Give ear to my words, O LORD, consider my He lieth in wait secretly as a lion in his den: he meditation. lieth in wait to catch the poor: he doth catch the 2 Hearken unto the voice of my cry, my King, and poor, when he draweth him into his net. my God: for unto thee will I pray. 10 He croucheth, and humbleth himself, that the 3 My voice shalt thou hear in the morning, poor may fall by his strong ones. 11 O LORD; in the morning will I direct my prayer He hath said in his heart, God hath forgotten: unto thee, and will look up. he hideth his face; he will never see it. 4 12 For thou art not a God that hath pleasure in Arise, O LORD; O God, lift up thine hand: forget wickedness: neither shall evil dwell with thee. not the humble. 5 The foolish shall not stand in thy sight: thou 13 Wherefore doth the wicked contemn God? he hatest all workers of iniquity. hath said in his heart, Thou wilt not require it. 6 Thou shalt destroy them that speak leasing: 14 Thou hast seen it; for thou beholdest mischief the LORD will abhor the bloody and deceitful man. -

First Peter 1:6-9 3-28-04 P

1 Psalm 5 April 3, 2016 PM Prayerbook of the Bible Psalms PS1605 A Morning Psalm INTRODUCTION: This is “March Madness” season … 1. … the NCAA Division I Basketball payoffs. 2. Last weekend 8 teams, known as the Elite Eight played one another to narrow the field down to the Final Four. a) The University of Virginia played Syracuse University (NY). b) The Virginia Cavaliers led by as many as 15 points, late into the game, Syracuse scored 20 points to Virginia’s 4 points in the closing minutes, including at one point 15 in a row! c) They won 68 to 62; and in the last 5:47 they outscored Virginia 9 to 4! d) Virginia was the top-seeded team in the Midwest Region. 3. Tony Bennett (Anthony Guy Bennett) is the coach of the Virginia basket ball team. He is an avowed Christian. a) After the game he was asked, “Coach, what do you say to your players after a loss like that?” b) He calmly smiled and said, “There’s an ancient Psalm that says, ‘Weeping may last for the night, but a shout of joy comes in the morning.’ This will be a weepy night, but the future of Virginia basketball looks great.” c) He was quoting Psalm 30:4-5, one of many Morning Psalms in the Psalter Sing praises to the Lord, O you his saints, and give thanks to his holy name. For his anger is but for a moment, and his favor is for a lifetime. Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning. -

“Prayers of Confession” — Psalm 5

“Prayers of Confession” Sunday, June 30, 2019 — Rev. Douglas J. Kortyna, Pastor Sermon Text: Psalm 5 Worship Theme: “The Covenant Community continually confesses their sin before the Lord.” Opening This morning’s text is going to take some time to get through. Therefore, I want to keep my opening short. But, I want us as a congregation to realize that this text has to do primarily with words. How we choose them, how we direct our words to God in worship, and the judgment that will occur for our words spoken in this life. Would you please turn with me to Psalm 5? TEXT SECTION I (Call to Worship) 5:0 - 5:1 – Psalm of singing. This would have been sung in the congregation, historically. Nothing needs to be said further. We first have a command or request directed towards the Lord.1 One of the things that has stood out to me thus far, when reading through the Psalter, is requests to the Lord are commands. This implies the language is stronger than “O, Lord please do this or that.” The Psalms are not polite prayers like we often pray. It is more like “Lord do this or that.” I think there is more urgency in the text. Thus we should pray this way, too! The commands issued towards the Lord are to “hear” and “consider.” Psalm 5 implies the person is overwhelmed with emotion. Perhaps even to the point of not being able to pray. But the Lord will answer the petitions of the covenant community who is inwardly groaning and unable to express themselves adequately.2 5:2 – We have a declarative statement of who the Psalmist is praying to. -

Agpeya English Ereader Test

The Agpeya 1 The Agpeya Book of the Hours Table of contents 2 Table of contents The Agpeya .............................................................................. 1 Table of contents ..................................................................... 2 Introduction to Every Hour ...................................................... 6 The Lord’s Prayer ..................................................................... 6 The Prayer of Thanksgiving ...................................................... 7 Psalm 50 .................................................................................. 9 PRIME .................................................................................... 11 Prime Psalms ....................................................................... 14 Prime Holy Gospel (St. John) ............................................... 34 Prime Litany ......................................................................... 36 The Gloria .............................................................................. 37 THE TRISAGION ...................................................................... 38 Intercession of the Most Holy Mother of God ...................... 40 Introduction to the Creed ...................................................... 41 The Creed .............................................................................. 41 Holy Holy Holy ..................................................................... 43 The Concluding Prayer of Every Hour .................................... 45 Table -

Psalm 5 Sermon Outline

Text: Psalm 5 Title : A Prayer for Your Enemies Date: 7/11/21 Intro: There is a certain amount of uncertainty for believers in America. We can sense the feeling that Christianity is not the accepted and even celebrated world view it once was in America. On our currency when you look at a dollar bill it says… in God we trust… not a surprise to anyone… but the popular consensus seems to be that is an antiquated, uneducated view held by those who really haven’t engaged with the real world out there… For some it is more than just antiquated it is harmful and wrong to promote a belief in God and should be opposed actively until those who call themselves christians are eradicated… Christopher Hitchens a popular thinker and opponent of Christianity said this when asked about his beliefs “ I am not even an atheist so much as I am an antitheist; I not only maintain that all religions are versions of the same untruth but I hold that the influence of churches, and the effect of religious belief is positively harmful.” When we recognize that the feeling of the popular culture is no longer for us but shifting it causes us to pause. We feel uncertain about who we are and what we believe. It can feel as if the walls are closing in around us, the world is growing increasingly secular, schools are banning christian prayers and expressions of faith, leaders are made to seem unloving and uncaring people by fighting for the rights of unborn babies or traditional Christian marriage values and believing God has given us our gender… We start to feel like enemies are everywhere… Rebecca Mclaughlin told this story while sitting in the park with her kids “ When my first daughter was four, we were playing in the sand at a local park. -

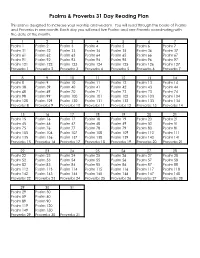

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

1 How to Begin Each Day in a Good Way Psalm 5 Intro. 1) Often We Run Into People Who Have What I Call “A Partly Cloudy Disposi

1 How to Begin Each Day in A Good Way Psalm 5 Intro. 1) Often we run into people who have what I call “a partly cloudy disposition with thunderstorms on the horizon.” They are angry, mad, discouraged. They are not having a good day and feel the need to share their misery with as many people as possible. Concerning these kinds of people we have created a popular saying: “He must have got up on the wrong side of the bed this morning.” In other words he began the day in a bad way rather than a good way, and it has stayed with him all day long. 2) David knew it was important to both begin and end each day in a good way. He knew the best way to do this is with prayer. In Psalms 3-6 we have prayers for the morning and evening. Psalm 3 is a morning prayer. Psalm 4 is an evening prayer. Psalm 5 is a morning prayer (v. 3). Psalm 6 is an evening prayer. The Bible teaches us from the rising of the sun to the setting of the same; our entire day should be bathed in prayer. 3) In this morning prayer David seeks the Lord with great intensity. He is opposed by those who would do him harm. Perhaps the background of this Psalm is also the rebellion of Absalom (Ps. 3-4). Combining the elements of Psalms of lament and confidence, we see David asking for guidance in the midst of his enemies and their slander (vs. -

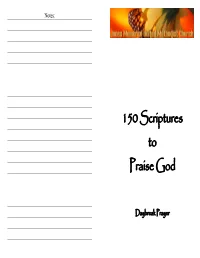

150 Scriptures to Praise

Notes: 150 Scriptures to Praise God Daybreak Prayer 1. Exodus 15:2 7. 2 Samuel 22:50 140. 1 Peter 1:3 before his glorious presence The LORD is my strength and my Therefore I will praise you, O Praise be to the God and Father without fault and with great joy— defense; he has become my LORD, among the nations; I will of our LORD Jesus Christ! In his 25 to the only God our Savior be salvation. He is my God, and I will sing the praises of your name. great mercy he has given us new glory, majesty, power and praise him, my father’s God, and I birth into a living hope through the authority, through Jesus Christ our will exalt him. 8. 1 Kings 8:56 resurrection of Jesus Christ from LORD, before all ages, now and “Praise be to the LORD, who has the dead, … forevermore! Amen. 2. Deuteronomy 32:3 given rest to his people Israel just I will proclaim the name of the as he promised. Not one word has 141. 1 Peter 1:7 146. Revelation 5:12 LORD. Oh, praise the greatness of failed of all the good promises he These have come so that the In a loud voice they sang: “Worthy our God! gave through his servant Moses proven genuineness of your is the Lamb, who was slain, to …” faith—of greater worth than gold, receive power and wealth and 3. Judges 5:3 which perishes even though wisdom and strength and honor Hear this, you kings! Listen, you 9.