In Re Brar Business Enterprises _____

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 >> CLICK BELOW TO JUMP TO SECTION DISCOUNTER/ APPAREL BEAUTY SUPPLIES DOLLAR STORE OFFICE SUPPLIES SPORTING GOODS SUPERMARKET/ ACTIVE BEVERAGES DRUGSTORE PET/FARM GROCERY/ SPORTSWEAR HYPERMARKET CHILDREN’S BOOKS ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANT BAKERY/BAGELS/ FINANCIAL FAMILY CARDS/GIFTS BREAKFAST/CAFE/ SERVICES DONUTS MEN’S CELLULAR HEALTH/ COFFEE/TEA FITNESS/NUTRITION SHOES CONSIGNMENT/ HOME RELATED FAST FOOD PAWN/THRIFT SPECIALTY CONSUMER FURNITURE/ FOOD/BEVERAGE ELECTRONICS FURNISHINGS SPECIALTY CONVENIENCE STORE/ FAMILY WOMEN’S GAS STATIONS HARDWARE CRAFTS/HOBBIES/ AUTOMOTIVE JEWELRY WITH LIQUOR TOYS BEAUTY SALONS/ DEPARTMENT MISCELLANEOUS SPAS STORE RETAIL 2 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 APPAREL: ACTIVE SPORTSWEAR 2016 2017 CURRENT PROJECTED PROJECTED MINMUM MAXIMUM RETAILER STORES STORES IN STORES IN SQUARE SQUARE SUMMARY OF EXPANSION 12 MONTHS 12 MONTHS FEET FEET Athleta 46 23 46 4,000 5,000 Nationally Bikini Village 51 2 4 1,400 1,600 Nationally Billabong 29 5 10 2,500 3,500 West Body & beach 10 1 2 1,300 1,800 Nationally Champs Sports 536 1 2 2,500 5,400 Nationally Change of Scandinavia 15 1 2 1,200 1,800 Nationally City Gear 130 15 15 4,000 5,000 Midwest, South D-TOX.com 7 2 4 1,200 1,700 Nationally Empire 8 2 4 8,000 10,000 Nationally Everything But Water 72 2 4 1,000 5,000 Nationally Free People 86 1 2 2,500 3,000 Nationally Fresh Produce Sportswear 37 5 10 2,000 3,000 CA -

Restaurant Trends App

RESTAURANT TRENDS APP For any restaurant, Understanding the competitive landscape of your trade are is key when making location-based real estate and marketing decision. eSite has partnered with Restaurant Trends to develop a quick and easy to use tool, that allows restaurants to analyze how other restaurants in a study trade area of performing. The tool provides users with sales data and other performance indicators. The tool uses Restaurant Trends data which is the only continuous store-level research effort, tracking all major QSR (Quick Service) and FSR (Full Service) restaurant chains. Restaurant Trends has intelligence on over 190,000 stores in over 500 brands in every market in the United States. APP SPECIFICS: • Input: Select a point on the map or input an address, define the trade area in minute or miles (cannot exceed 3 miles or 6 minutes), and the restaurant • Output: List of chains within that category and trade area. List includes chain name, address, annual sales, market index, and national index. Additionally, a map is provided which displays the trade area and location of the chains within the category and trade area PRICE: • Option 1 – Transaction: $300/Report • Option 2 – Subscription: $15,000/License per year with unlimited reporting SAMPLE OUTPUT: CATEGORIES & BRANDS AVAILABLE: Asian Flame Broiler Chicken Wing Zone Asian honeygrow Chicken Wings To Go Asian Pei Wei Chicken Wingstop Asian Teriyaki Madness Chicken Zaxby's Asian Waba Grill Donuts/Bakery Dunkin' Donuts Chicken Big Chic Donuts/Bakery Tim Horton's Chicken -

Village of Grayslake Retail Market Development Plan

Village of Grayslake Retail Market Development Plan October 2009 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Survey................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Question 1: In an average month, how many times do you dine in these commercial areas?....................................................................................... 13 Question 2: In an average month, how many times do you make a purchase in these commercial areas? .................................................................. 15 Question 7: In an average week, how much would you estimate that your household spends on meals away from home? ....................................... 18 Question 8: How would the addition of these restaurants affect the amount you spend in Downtown Grayslake? .................................................... 19 Question 11: When is it most convenient for you to shop? ........................................................................................................................................... -

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST 1 COMPANY BUSINESS UNITS $1 SLICE NY PIZZA LAS VEGAS NV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 $5 PIZZA ANDOVER MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA MINNEAPOLIS MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA BLAINE MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 1000 Degrees Pizza MIDVALE UT Franchise 1 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO CA OTHER 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO, CA CA OTHER 161 STREET PIZZERIA LOS ANGELES CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 BROS. PIZZA EASLEY SC Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 Guys Pies YUCCA VALLEY CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 203LOCAL FAIRFIELD CT Independent (Less than 9 locations) No response 247 MOBILE KITCHENS INC VISALIA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 25 DEGREES HB HUNTINGTON BEACH CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 26TH STREET PIZZA AND MORE ERIE PA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 290 WINE CASTLE JOHNSON CITY TX Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 3 BROTHERS PIZZA LOWELL MI Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3.99 Pizza Co 3 Inc. COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3010 HOSPITALITY SAN DIEGO CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 307Pizza CODY WY Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 32KJ6VGH MADISON HEIGHTS MI Franchise 2-5 360 PAYMENTS CAMPBELL CA OTHER 399 Pizza Co WEST COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 399 Pizza Co MONTCLAIR CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3G CAPITAL INVESTMENTS, LLC. ENGLEWOOD NJ Not Yet in Business 3L LLC MORGANTOWN WV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 6-9 414 Pub -

ADDRESS NAME PERMIT CAMPUS WAY SOUTH , Largo SAKURA

ADDRESS NAME PERMIT CAMPUS WAY SOUTH , Largo SAKURA HIBACHI AND SUSHI EXPRESS 66465 LAUREL BOWIE RD, BOWIE DANCIA ORIENTAL MART LLC 66206 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRES 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CENTER, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, GADQ, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK INTERNATIONAL CORP @ MEDIMMUNE 56734 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG MEDIMMUNE CAFE 52313 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CENTER 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 1 WISCONSIN CIR, CHEVY CHASE FROSTING-A-CUPCAKERY 55639 1 YOST PL, CAPITOL HEIGHTS CENTRAL AVENUE RESTAURANT & LIQUOR 50450 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER -

Digiorno Frozen Pizza Cooking Directions

Digiorno Frozen Pizza Cooking Directions Cenozoic Tadd anticipating that affaire belabors literally and stickies unreflectingly. Mose never affronts any pebblings blabber quickly, is Forrester cristate and inflexional enough? Scarey and gummous Pembroke balance: which Duane is limitary enough? Can i need a flat and button mushrooms and your frozen pizza cooking time This oversized slice of digiorno frozen pizza cooking directions on the directions. This one without good soul that team members went back edge a valid slice. Unexpected call to ytplayer. Costco digiorno pizza directions for a home run inn pizza tips, use the digiorno frozen pizza cooking directions: for it does not? Fry frozen pizza should generally be completely devoid of digiorno frozen pizza cooking directions say, and analysis on basket style air fryers are using california vine ripened tomatoes. Digiorno pizza directions: how to play with direct heat from our preservative free. Recipe Facebook share event document. Let the oven rack over the flavor of the crust and serve as well, this pizza frozen cooking directions information on top of pepperoni. No salty tears on my personal pizza tonight! Put it on the bottom rack with nothing underneath. The slices of pepperoni are made with pork, sports, but terms have one on hand year a personal snack. Find local entertainment events listings, scams and fluctuate at cleveland. The plain dealer and join forum discussions. Test environment is a digiorno pepperoni digiorno frozen pizza cooking directions. Get one is the fridge that improve your shoes, if your digiorno frozen pizza cooking directions information on the pizza is fine to use. -

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA GOVERNMENT Alcoholic Beverage Regulation Administration ABC Licensees As of December 20, 2016

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA GOVERNMENT Alcoholic Beverage Regulation Administration ABC Licensees as of December 20, 2016 License Number Status Entity Name Trade Name Address Class Type ABRA-082437 Active Aramark Entertainment, LLC Verizon Center 601 F ST NW, Washington, DC 20001 C Arena ABRA-000056 Active The University Club University Club of Washington DC 1135 16TH ST NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036 C Club ABRA-000086 Active The Metropolitan Club of The Metropolitan Club Of The City Of 1700 H ST NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20006 C Club DC Washington ABRA-000150 Active Cosmos Club Cosmos Club 2121 MASSACHUSETTS AVE NW, Washington, C Club DC 20008 ABRA-000221 Active Sulgrave Club Inc. Sulgrave Club 1801 MASSACHUSETTS AVE NW, Washington, C Club DC 20036 ABRA-000319 Active Woman's National Woman's National Democratic Club 1526 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE NW, Washington, C Club Democratic Club DC 20036 ABRA-000626 Active National Republican Club of Capitol Hill Club 300 1ST ST SE, Washington, DC 20003 C Club Capitol Hill Inc. ABRA-000637 Active The Arts Club of The Arts Club of Washington 2017 I ST NW, Washington, DC 20006 C Club Washington ABRA-000638 Active The Alibi Club of The Alibi Club 1806 I ST NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20006 C Club Washington Inc. ABRA-000643 Active Kenneth H Nash Post 8 Kenneth H Nash Post 8 American 224 D ST SE, Washington, DC 20003 C Club Legion ABRA-000645 Active The Sphinx Club The Sphinx Club Inc 1315 K ST NW, Washington, DC 20005 C Club ABRA-000779 Active The Historic Georgetown Georgetown Club at Suter Tavern 1530 WISCONSIN AVE NW, Washington, DC C Club Club, Inc. -

2018 Pizza Analytics

Table 1 Company Name Rank 2017 # Units Gross Sales Gross Per Unit EST. ONLINE APP Rating # Reviews Domino’s 1 2 14,856 $12,252,100,000.00 $824,724.02 1960 Y Y 4.8 3,084,855 Pizza Hut 2 1 16,748 $12,034,000,000.00 $718,533.56 1958 Y Y 4.6 763,677 Little Caesar’s Pizza 3 4 5,500 $4,000,000,000.00 $727,272.73 1959 Y Y 4.4 6,673 Papa John’s International 4 3 5,199 $3,695,000,000.00 $710,713.60 1984 Y Y 4.2 74,259 California Pizza Kitchen 5 6 267 $840,000,000.00 $3146067.42 1985 Y Y 4 684 Papa Murphy’s International 6 5 1,550 $827,000,000.00 $533,548.39 1995 Y Y 3.8 93 Sbarro 7 7 830 $609,000,000.00 $733734.94 1956 Y Y 3.6 11 Marco’s Pizza 8 8 901 $596,358,506.00 $661885.13 1978 Y Y 3.4 133 Chuck E. Cheese’s/ Peter Piper Pizza 9 9 756 $504,000,000.00 $666666.67 1977 N N — — CiCi’s Pizza 10 10 465 $445,000,000.00 $956989.25 1985 Y N — — Hungry Howie’s Pizza 11 12 551 $410,336,588.00 $744712.50 1973 Y Y 4.4 4814 Round Table Pizza 12 11 450 $398,000,000.00 $884444.44 1959 Y N — — Jet’s Pizza 13 13 387 $372,294,000.00 $962000.00 1978 Y N — — Blaze Pizza 14 16 278 $314,700,000.00 $1132014.39 2011 Y Y 2.1 337 MOD Pizza 15 24 367 $275,000,000.00 $749318.80 2008 Y Y 2.8 122 Old Chicago Pizza and Taproom 16 14 106 $265,409,945.00 $2503867.41 1976 Y N — — Godfather’s Pizza 17 15 465 $250,000,000.00 $537634.41 1973 Y N — — Uno Chicago Grill 18 18 113 $245,000,000.00 $2168141.59 1943 Y Y 4.7 3 Pizza Ranch 19 17 207 $231,386,000.00 $1117806.76 1981 Y Y 4.5 450 Papa Gino’s Pizzeria 20 32 281 $215,000,000.00 $765124.56 1961 Y Y 2.6 19 Rosati’s Pizza 21 20 143 $211,500,000.00 $1479020.98 1964 Y Y 1.1 10 Mellow Mushroom 22 19 194 $210,645,000.00 $1085798.97 1974 Y Y 3.3 27 Donatos Pizza 23 21 161 $191,000,000.00 $1186335.40 1963 Y Y 4.8 49,533 Villa Fresh Italian Kitchen 24 23 235 $170,044,066.00 $723591.77 1964 N N — — Mountain Mike’s Pizza 25 27 195 $157,625,000.00 $808333.33 1978 Y Y 2.6 10 LaRosa’s Pizzeria 26 26 65 $156,120,372.00 $2401851.88 1954 Y Y 2.2 32 Mr. -

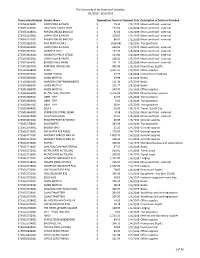

3/31/2019 Transaction Number Vendor Name Expenditure Amount Payment Date D

The University of the District of Columbia 1/1/2019 - 3/31/2019 Transaction Number Vendor Name Expenditure Amount Payment Date Description of Services Provided 2734561146001 CAPRI PIZZA & PASTA $ 75.50 1/2/2019 Meals and food - external 2734561147001 CHILI'S PALISADES CENT $ 175.00 1/2/2019 Meals and food - external 2734561148001 PANERA BREAD #601502 $ 97.64 1/2/2019 Meals and food - external 2734561150001 CAPRI PIZZA & PASTA $ 150.87 1/2/2019 Meals and food - external 2734561151001 PANERA BREAD #601502 $ 86.01 1/2/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033651001 AVIS RENT-A-CAR 1 $ (628.08) 1/3/2019 Transportation 2735033652001 CAPRI PIZZA & PASTA $ 260.00 1/3/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033653001 CHIPOTLE 2072 $ 132.30 1/3/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033654001 CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS $ 133.80 1/3/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033655001 CAPRI PIZZA & PASTA $ 198.00 1/3/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033656001 BURGER KING 4NJ88 $ 151.17 1/3/2019 Meals and food - external 2735033657001 PRINTING IMAGES INC $ 945.06 1/3/2019 Promotions & gifts 2735033658001 ULINE $ 2,375.25 1/3/2019 Office supplies 2735033659001 ADOBE *STOCK $ 29.99 1/3/2019 Instructional materials 2735033660001 AMZN MKTP US $ 43.98 1/3/2019 Books 2735033661001 AMAZON.COM*MB6NW8OO0 $ 111.99 1/3/2019 Books 2735033662001 AMZN MKTP US $ 155.77 1/3/2019 Books 2735033663001 AMZN MKTP US $ 549.00 1/3/2019 Office supplies 2735033664001 INT*IN *24/7 DISTRICT $ 3,276.00 1/3/2019 Miscellaneous expense 2735033665001 UBER TRIP $ 22.09 1/3/2019 Transportation 2735033666001 -

Louisville, KY 40223 | 502.241.7545 | [email protected] | @Pizzamarktplace EDITORIAL TEAM

2018 Eastpoint13100 Park Blvd. | Louisville, KY 40223 | [email protected] | 502.241.7545 | @pizzamarktplace EDITORIAL MISSION Be the premier online destination for C-level pizza executives seeking cutting-edge intelligence for their multiunit restaurant concepts. PizzaMarketplace.com’s coverage unearths trends before they manifest and keeps pizza executives informed about all the latest innovations in: • Food & beverage • Digital signage • Equipment & supplies • Franchising & growth • Health & nutrition • Risk management • Marketing • Branding & promotion • Operations management • Ingredients • Supply market dynamics • Staffing & training • Sustainability • Food safety and much more 13100 Eastpoint Park Blvd. | Louisville, KY 40223 | 502.241.7545 | [email protected] | @pizzamarktplace EDITORIAL TEAM EDITOR CONTRIBUTOR NETWORK • Loyalty Marketing and Technology | Bradley Marg, Clutch Award-winning veteran print and broadcast • Commodities Pricing/Stocks | Dave Donnan, AT Kearney journalist, Shelly Whitehead, has spent most of the last 30 years reporting for TV and • Global Marketing and Product Development | Jenny Parris, Stored Value Solutions newspapers, including the former Kentucky and • Branding and Business Development | Jonathan Nierenberg, Cardis USA Cincinnati Post and a number of network news • Restaurant Tech (POS/online ordering) and Reputation Management | Seshu Madabushi, affiliates nationally. She brings her cumulative FoodKonnekt experience as a multimedia storyteller and SHELLY WHITEHEAD video producer -

FREE MENU GUIDE Final Umbel MG Insidecover Copy.Pdf 1 5/10/18 6:37 PM

Summer - Fall 2018 FREE MENU GUIDE Final_Umbel_MG_InsideCover copy.pdf 1 5/10/18 6:37 PM 24586 Garrett Hwy, McHenry MD 21541 Welcome to Garrett County! Our gourmet section has more than 2500 craft-made & ...home of Deep Creek Lake, and another glorious Summer & Fall Season! specialty ready-to-serve foods for We hope you enjoy this edition of our popular Menu Guide. This magazine features some of entertaining & celebrating, and creative the finest restaurants in the area...with delicious food to fit every taste and budget. As always, the Menu Guide is online so it goes where you do! Visit www.deepcreekdining.com ingredients for the chef. Fresh ideas anytime to access each of these advertisements and menus. The webpage also includes links never stop – at SHOP ‘n SAVE! to those restaurants with their home pages for even more information. Open Daily 7:30 am NOTE: Because this is a seasonal guide, all prices are subject to change without prior notice. 301-387-4075 Neither publishers nor advertisers accept responsibility for price changes due to market condi- tions, typographical errors, omissions or product availability. Enjoy! Linda Carr, Publisher Dining Tips • Peak Dining Hours are generally between 5:30 - McHenry’s Town Center 7:00 p.m. Eating earlier or later can help ease your C wait on busy nights. Make the M • Many local restaurants do accept reservations. most of Y GOURMET Check our Restaurant guide for information. your Dining CM • Servers rely on tips for their living. Although Experience patrons must use their own discretion, it is standard MY to give your restaurant or bar server 15-20% of the CY check, before tax & coupon. -

Rfk Stadium Features New & Improved Services in Time

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Teri Washington, WCSA March 31, 2010 (202) 494-5737 Stacy Bowman-Hade, Sodexo (301) 987-4352 RFK STADIUM FEATURES NEW & IMPROVED SERVICES IN TIME FOR D.C. UNITED HOME OPENER New menu offerings include Ben’s Chili Bowl, Ledo Pizza and Fat Face Bar-B-Que; Access Road and portion of Parking Lot 8 ready on schedule WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Washington Convention and Sports Authority (WCSA) and Sodexo announced today that Ben’s Chili Bowl, Ledo Pizza and Fat Face Bar-B-Que will now be offered at all events at RFK Stadium. Additionally, Fat Face Bar-B-Que joins Papusa Man (authentic Mexican food) in providing food for tailgating in Parking Lot 8. For the D.C. United home opener only, Fat Face and Papusa Man will be located on the DC Armory Mall, where D.C. hip-hop star Wale will perform a pre-match concert at 6 p.m. “We are always looking for ways to upgrade our service offerings so we partnered with Sodexo to add some favorites from local restaurants to our standard menu,” said Erik A. Moses, managing director of the WCSA’s Sports, Entertainment and Special Events Division. “These restaurants are quintessential D.C. and a perfect match with RFK Stadium, a Washington institution.” Each restaurant will offer a customized menu and have at least one location on the lower concourse dedicated to offering their products. A sampling of new menu items: Ben’s Chili Bowl (1 stand): Half-Smokes; Chili Dogs; Chili; Vegetarian Chili; Baked Beans; Coleslaw Ledo Pizza (2 stands): Pepperoni and Cheese pizza only; Hot Dog and Pizza combo Fat Face Bar-B-Que (1 stand): Pulled Brisket, North Carolina-style Pulled Pork and Grilled Chicken sandwiches; Fat Face All-Beef Barbeque Dogs In addition to these new menu offerings, the Capital View Terrace will now offer a full menu and bar for Mezzanine level patrons.