Theatre As a Sample-Based Artform: an Interview with JQ (Q Brothers)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Companiescompanies

PrivatePrivate CompaniesCompanies Private Company Profiles @Ventures Kepware Technologies Access 360 Media LifeYield Acronis LogiXML Acumentrics Magnolia Solar Advent Solar Mariah Power Agion Technologies MetaCarta Akorri mindSHIFT Technologies alfabet Motionbox Arbor Networks Norbury Financial Asempra Technologies NumeriX Asset Control OpenConnect Atlas Venture Panasas Autonomic Networks Perimeter eSecurity Azaleos Permabit Technology Azimuth Systems PermissionTV Black Duck Software PlumChoice Online PC Services Brainshark Polaris Venture Partners BroadSoft PriceMetrix BzzAgent Reva Systems Cedar Point Communications Revolabs Ceres SafeNet Certeon Sandbridge Technologies Certica Solutions Security Innovation cMarket Silver Peak Systems Code:Red SIMtone ConsumerPowerline SkyeTek CorporateRewards SoloHealth Courion Sonicbids Crossbeam Systems StyleFeeder Cyber-Ark Software TAGSYS DAFCA Tatara Systems Demandware Tradeware Global Desktone Tutor.com Epic Advertising U4EA Technologies ExtendMedia Ubiquisys Fidelis Security Systems UltraCell Flagship Ventures Vanu Fortisphere Versata Enterprises GENBAND Visible Assets General Catalyst Partners VKernel Hearst Interactive Media VPIsystems Highland Capital Partners Ze-gen HSMC ZoomInfo Invention Machine @Ventures Address: 187 Ballardvale Street, Suite A260 800 Menlo Ave, Suite 120 Wilmington, MA 01887 Menlo Park, CA 94025 Phone #: (978) 658-8980 (650) 322-3246 Fax #: ND ND Website: www.ventures.com www.ventures.com Business Overview @Ventures provides venture capital and growth assistance to early stage clean technology companies. Established in 1995, @Ventures has funded more than 75 companies across a broad set of technology sectors. The exclusive focus of the firm's fifth fund, formed in 2004, is on investments in the cleantech sector, including alternative energy, energy storage and efficiency, advanced materials, and water technologies. Speaker Bio: Marc Poirier, Managing Director Marc Poirier has been a General Partner with @Ventures since 1998 and operates out the firm’s Boston-area office. -

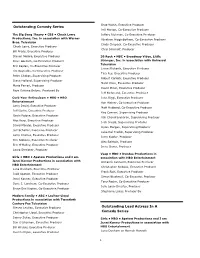

Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming Less Than One Hour)

Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Outstanding Animated Program (For Corey Campodonico, Producer Programming Less Than One Hour) Alex Bulkley, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer Creature Comforts America • Don’t Choke To Death, Tom Root, Head Writer Please • CBS • Aardman Animations production in association with The Gotham Group Jordan Allen-Dutton, Writer Mike Fasolo, Writer Kit Boss, Executive Producer Charles Horn, Writer Miles Bullough, Executive Producer Breckin Meyer, Writer Ellen Goldsmith-Vein, Executive Producer Hugh Sterbakov, Writer Peter Lord, Executive Producer Erik Weiner, Writer Nick Park, Executive Producer Mark Caballero, Animation Director David Sproxton, Executive Producer Peter McHugh, Co-Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind • Jacqueline White, Supervising Producer FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Kenny Micka, Producer James L. Brooks, Executive Producer Gareth Owen, Producer Matt Groening, Executive Producer Merlin Crossingham, Director Al Jean, Executive Producer Dave Osmand, Director Ian Maxtone-Graham, Executive Producer Richard Goleszowski, Supervising Director Matt Selman, Executive Producer Tim Long, Executive Producer King Of The Hill • Death Picks Cotton • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television in association with 3 Arts John Frink, Co-Executive Producer Entertainment, Deedle-Dee Productions & Judgemental Kevin Curran, Co-Executive Producer Films Michael Price, Co-Executive Producer Bill Odenkirk, Co-Executive Producer Mike Judge, Executive Producer Marc Wilmore, Co-Executive Producer Greg Daniels, Executive Producer Joel H. Cohen, Co-Executive Producer John Altschuler, Executive Producer/Writer Ron Hauge, Co-Executive Producer Dave Krinsky, Executive Producer Rob Lazebnik, Co-Executive Producer Jim Dauterive, Executive Producer Laurie Biernacki, Animation Producer Garland Testa, Executive Producer Rick Polizzi, Animation Producer Tony Gama-Lobo, Supervising Producer J. -

Current Issue

1/2 bmf 1/2 ss ad:Layout 1 6/3/10 4:28 PM Page 1 july 8 – august 22, 2010 2010 10 - august BARDSUMM ERSCAPE 10 Bard SummerScape presents seven Opera Bard Music Festival Twenty-first Season Tickets and information: weeks of opera, dance, music, 845-758-7900 THE DISTANT SOUND (Der ferne Klang) BERG AND HIS WORLD | july fishercenter.bard.edu 36 drama, film, cabaret, and the 21st July 30, August 1, 4, 6 August 13–15 and 20–22 Sung in German with English supertitles Two weekends of concerts, panels, and annual Bard Music Festival, this year vol. Music and libretto by Franz Schreker other events bring the musical world of exploring the works and world of American Symphony Orchestra Alban Berg vividly to life. CREATIVE LIVING IN THE HUDSON VALLEY composer Alban Berg. SummerScape Conducted by Leon Botstein Directed by Thaddeus Strassberger Operetta takes place in the extraordinary Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. The first fully-staged North American Richard B. Fisher Center for the THE CHOCOLATE SOLDIER production of an important but rarely August 5 – August 15 Performing Arts and other venues performed opera bearing a gripping story Music by Oscar Straus and a stunning, melodic musical score. on Bard College’s stunning Mid- Conducted by James Bagwell Hudson River Valley campus. Dance Directed by Will Pomerantz Straus's delightful 1908 operetta is an TRISHA BROWN DANCE COMPANY adaptation of George Bernard Shaw's July 8, 9, 10, 11 Arms and the Man. Choreography by Trisha Brown Twelve Ton Rose (excerpt), Foray Forêt, Theater You can see us, L’Amour au théâtre JUDGMENT DAY Film Festival July 14 –25 By Ödön von Horváth THE BEST OF G. -

2000 MFA, Scenic Design, Yale School of Drama 1995 BS, Theater

Pace University office: 212-618-6106 www.lukecantarella.com 140 William Street #606 mobile: 646-263-4989 e-mail: [email protected] New York, NY 10038 or [email protected] education: 2000 M.F.A., Scenic Design, Yale School of Drama 1995 B.S., Theater, Northwestern University other training: School of the Art Institute, Art Students League, The Drawing Center, Columbia University (Summer Intensive in German) university experience: 2012-present Associate Professor/Pace University Head of Set Design (2013-2016): Responsibilities include undergraduate teaching, course development, mentoring student designers, 1st year student advisement Head of Production and Design (2012-2013): Responsibilities include undergraduate teaching, establishing a curriculum for new BFA program in Production & Design, recruiting and retaining students, hiring and mentoring new faculty, student mentorship, production planning and budgeting. 2008-12 Associate Professor/University of California, Irvine Head of Set Design Program: Responsibilities include teaching both graduate and undergraduate courses, curriculum design, recruiting and retaining students, mentorship, thesis reviews, production planning and budgeting. Tenure granted: June 2012 scenic design projects: For the following projects (plays, musicals, dances & live performance), I was in charge of designing the scenery. Responsibilities included collaborating with directors, playwrights, choreographers and other designer to analyze a text, forming design ideas, researching of visual culture, creating design documents (sketches, models, technical drawings, etc.), specifying paint colors and finishes, and the supervising assistants and fabricators including painters, carpenters, masons, furniture-makers, upholsterers and properties masters. Projects listed below show the name of the play, name of the playwright, name of the director and theater or producer. Productions in bold indicate world premieres. -

Nomination Press Release

Brad Walsh, Executive Producer Outstanding Comedy Series Jeff Morton, Co-Executive Producer The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Jeffery Richman, Co-Executive Producer Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Abraham Higginbotham, Co-Executive Producer Bros. Television Cindy Chupack, Co-Executive Producer Chuck Lorre, Executive Producer Chris Smirnoff, Producer Bill Prady, Executive Producer Steven Molaro, Executive Producer 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Dave Goetsch, Co-Executive Producer Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television Eric Kaplan, Co-Executive Producer Lorne Michaels, Executive Producer Jim Reynolds, Co-Executive Producer Tina Fey, Executive Producer Peter Chakos, Supervising Producer Robert Carlock, Executive Producer Steve Holland, Supervising Producer Marci Klein, Executive Producer Maria Ferrari, Producer David Miner, Executive Producer Faye Oshima Belyeu, Produced By Jeff Richmond, Executive Producer Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO John Riggi, Executive Producer Entertainment Ron Weiner, Co-Executive Producer Larry David, Executive Producer Matt Hubbard, Co-Executive Producer Jeff Garlin, Executive Producer Kay Cannon, Supervising Producer Gavin Polone, Executive Producer Vali Chandrasekaran, Supervising Producer Alec Berg, Executive Producer Josh Siegal, Supervising Producer David Mandel, Executive Producer Dylan Morgan, Supervising Producer Jeff Schaffer, Executive Producer Luke Del Tredici, Supervising Producer Larry Charles, Executive Producer Jerry Kupfer, Producer Tim Gibbons, Executive -

26Th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards Recipients Announced The

Press Contact: Thomas Onorato [email protected] Max Wixom [email protected] 646.613.8733 26th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards Recipients Announced The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity Receives Outstanding Play New York, NY (May 1, 2011) – This evening, the 2011 Lucille Lortel Awards for Outstanding Achievement Off-Broadway were handed out to recipients in 14 categories and 3 special awards. This year’s ceremony will benefit The Actors Fund. A full list of recipients follows below. The Ceremony drew an amazing group of celebrity presenters, the Off-Broadway community and a full bevy of entertainment insiders, held at NYU Skirball Center at 566 LaGuardia Place Samantha Bee of THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART and Zach Braff of THE HIGH COST OF LIVING and Off-Broadway’s “Trust” in 2010 co-hosted the 7 PM event. Themed “Off-Broadway Rocks”, the Ceremony featured high octane performances by Everett Bradley (Hall & Oates - http://www.everettbradley.com), Orfeh (Love, Janis - http://www.orfeh.com), The Bettys (http://thebettysrock.com) and New York City’s own rock-n-roll nightlife impresario, Michael T. doing pieces from the Off-Broadway canon with a rock sound. A diverse group of notable presenters for the evening include Kevin Kline, Olympia Dukakis, Blythe Danner, AnnaLynne McCord, Natasha Lyonne, Matthew Settle, Hilarie Burton, Eddie Kaye Thomas, Annabella Sciorra, Michael T. Weiss, Mike Birbiglia, Lily Rabe, Josh Hamilton, Matthew Settle, Ron Rifkin, T.V. Carpio, Chris Benz, Valerie Harper, Arian Moayed, Terrence McNally, Anson Mount, Anthony Rapp, Sanjaya Malakar, Tammy Blanchard, Kate Shindle, Billy Porter, Seth Numrich, Christopher Hanke, Jeremy Strong and Patina Miller. -

Stewartwhitley Resume 11.12.19

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors/Partners Joey Montenarello, CSA Casting Director Sam Yabrow, Casting Director Luke Schaffer, Casting Assistant Resume as of 11.12.2019 _________________________________________________________________ CURRENT & ONGOING: TV/FILM: NEW AMERICANS Sept 2019 - present James Mills (Writer/Dir.), Tony Estrada, Travis Mauck , Jona Ward (Prod.) BRUISED FRUIT TASTES SWEETER Nov 2019 Jake Kolton (Writer/Dir.), Casey Bader (Prod.) TINY PRETTY THINGS Netflix June 2019 Sergio Navarretta (Dir.) NY Casting ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST NBC Lionsgate TV Pilot March 2019 Richard Shepard (Dir.), Austin Winsberg (Writer) NY Casting UNTITLED HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN PROJECT Reading & Demo, New York, NY November 2018 - Ongoing Neil Meron, Mark Nicholson, Stephen Schwartz, David Magee, Fox (Prod.) By: David McGee, Stephen Schwartz THEATRE: HADESTOWN Theater, Broadway – Walter Kerr Theater March 2019 – Open Ended ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Stewart/Whitley 213 West 35th Street Suite 804 New York, NY 10001 212.635.2153 Mara Isaacs, Hunter Arnold, Dale Franzen (Prod.) Rachel Chavkin (Dir.), David Newmann (Choreo.) By: Anais Mitchell THE LIGHTNING THIEF Theater, Broadway – Longacre Theater September 2019 – January 2020 TheaterWorks USA, Martian Entertainment, Victoria Lang, Lisa Chanel, Jennifer Doyle, Roy Lennox, Mary Maggio, Van Dean, and Meredith Lucio (Prod.) Stephen Brackett (Dir.), Patrick McCollum (Choreo.) By: Rob Rokicki & Joe Tracz CHICAGO THE -

The Bomb-Itty of Errors

2007—2008 SEASON THE BOMB-ITTY OF ERRORS by Jordan Allen-Dutton, Jason Catalano, Gregory Qaiyum and CONTENTS Erik Weiner 2 The 411 3 A/S/L & RMAI Music by Jeffrey Qaiyum 4 FYI 5 F2F 6 HTH 7 RBTL 8 IRL 11 B4U 12 SWDYT? MISSOURI ARTS COUNCIL MIHYAP: TOP TEN WAYS TO STAY CONNECTED AT THE REP At The Rep, we know that life moves 10. TBA Ushers will seat your school or class as a group, fast—okay, really so even if you are dying to mingle with the group from the fast. But we also all-girls school that just walked in the door, stick with your know that some friends until you have been shown your section in the things are worth slowing down for. We believe that live theatre. theatre is one of those pit stops worth making and are 9. SITD The house lights will dim immediately before the excited that you are going to stop by for a show. To help performance begins and then go dark. Fight off that oh-so- you get the most bang for your buck, we have put together immature urge to whisper, giggle like a grade schooler, or WU? @ THE REP—an IM guide that will give you yell at this time and during any other blackouts in the show. everything you need to know to get at the top of your 8. SED Before the performance begins, turn off all cell theatregoing game—fast. You’ll find character descriptions phones, pagers, beepers and watch alarms. -

Outstanding Animated Program (For Chris Clements, Directed by Programming Less Than One Hour) Matt Selman, Written By

Scott Brutz, Animation Timer Outstanding Animated Program (for Chris Clements, Directed By Programming Less Than One Hour) Matt Selman, Written by Avatar: The Last Airbender • City Of Walls And Secrets • South Park • Make Love, Not Warcraft • Comedy Central • Nick • Nickelodeon Animation Studio Central Productions Michael Dante DiMartino, Executive Producer Trey Parker, Executive Producer/Directed by/Written by Bryan Konietzko, Executive Producer Matt Stone, Executive Producer Eric Coleman, Executive Producer Anne Garefino, Executive Producer Aaron Ehasz, Co-Executive Producer/Head Writer Frank C. Agnone II, Supervising Producer Tim Hedrick, Written by Kyle McCulloch, Producer Lauren MacMullan, Directed by Eric Stough, Director of Animation Yu Jae Myoung, Animation Director/Timing Director SpongeBob SquarePants • Bummer Vacation / Wig Struck Robot Chicken • Lust For Puppets • Cartoon Network • • Nick • Nickelodeon Animation Studio in association with ShadowMachine Films United Plankton Pictures, Inc. Seth Green, Executive Producer/Writer/Directed by Stephen Hillenburg, Executive Producer Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Writer Paul Tibbitt, Supervising Producer Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Tom Yasumi, Animation Director/Timer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer Alan Smart, Animation Director/Supervising Director/Timer Corey Campodonico, Producer Casey Alexander, Storyboard Director/Written by Alex Bulkley, Producer Chris Mitchell, Storyboard Director/Written by Tom Root, Head Writer Luke Brookshier, Storyboard Director/Written by -

Narrative Strategies in Shakespearean Productions on Twenty-First-Century European Stages

NARRATIVE STRATEGIES IN SHAKESPEAREAN PRODUCTIONS ON TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY EUROPEAN STAGES by STEPHANIE MICHAELA SCHNABEL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF LITERATURE Shakespeare Institute School of English, Drama and American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. THESIS ABSTRACT This thesis is on the one hand part of the wider field of ‘European Shakespeare’ studies which have become more and more popular in recent years. On the other hand it attempts to propose a new way at researching ‘Shakespeare’ in such a context, thereby also trying to answer the ever persistent question of how much ‘Shakespeare’ is essential for a performance to be regarded as ‘Shakespearean’? There has been a constant striving for a more trans-national approach in this field –some successful, some futile– and therefore national borders have been disregarded in this research project. This thesis instead focuses on the different kinds of media or narrative strategies employed in theatre: each chapter is concerned with a change in narration. -

Specials Under $15!!!

Specials Under $15!!! Action/Adventure Blitz (2011) DVD MA15+ Action/Adventure Cat#: R-110503-9 RRP $39.95 SALE $14.20 A tough cop is dispatched to take down a serial killer who has been targeting police officers. Jason Statham heads the cast of BLITZ as the tough uncompromising ... Jason Statham, Paddy Considine, Aidan Gillen, Zawe Ashton, David Morrissey, Richard Riddell, Des Barron, John Burton, Taya De La Cruz, Nabil Elouahabi, Luke Evans, Rebecca Eve, Elly Fairman, Gregory Finnegan, Rishi Ghosh Courage Under Fire (1996) BR M Action/Adventure Cat#: 4132SBO RRP $29.95 SALE $14.20 "In wartime, the first casualty is always truth." January 1991. The world is watching the Gulf War. Day and night, millions tune in to CNN-TV to see a ... Denzel Washington, Meg Ryan, Lou Diamond Phillips, Michael Moriarty, Matt Damon, Seth Gilliam, Bronson Pinchot, Scott Glenn Expendables, The (2010) DVD MA15+ Action/Adventure Cat#: R-109415-9 RRP $19.95 SALE $14.20 Barney Ross leads the "Expendables", a band of highly skilled mercenaries including knife enthusiast Lee Christmas, martial arts expert Yin Yang, heavy ... Sylvester Stallone, Jason Statham, Jet Li, Dolph Lundgren, Eric Roberts, Randy Couture, Steve Austin, David Zayas, Giselle Itie, Charisma Carpenter, Gary Daniels, Terry Crews, Mickey Rourke, Amin Joseph, Senyo Amoaku G.I. Joe - The Rise of Cobra (2009) DVD M Action/Adventure Cat#: AUDVD7722 RRP $29.95 SALE $14.20 Everyone's favourite action heroes come to DVD and Blu-ray in this massive action blockbuster. Paramount Pictures and Hasbro, whose previous collaboration ... Dennis Quaid, Christopher Eccleston, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Sienna Miller, Marlon Wayans, Channing Tatum, Hurt Locker, The (2009) DVD MA15+ Action/Adventure Cat#: R-108924-9 RRP $24.95 SALE $14.20 In the summer of 2004, Bravo Company are at the volatile center of the war, part of a small counterforce trained to handle homemade bombs or Improvised .. -

Bomb-Itty of Errors at HV Shakespeare Fest (291KBMB PDF)

www.TheExaminerNews.com July 27 - August 2, 2010 9 Due to Poor Leadership, New York State Budget Dead on Arrival It’s finally arrived! Washington to give back the $1.1 billion in of New York State are witnessing the most rid ourselves of all these people who have Not the fully Medicaid aid they had taken away from us incompetent, cowardly, sorry excuses breached the public trust by firing them all completed New for THEIR own budgetary constraints. This for lawmakers in our long history. It is on November 3rd. They have failed us by York State budget, is how our legislators expect to plug the impossible to expect New York to become destroying our wonderful state by making heaven forbid, but $9.2 billion budget gap. Add in unrealistic a place that people will want to live in and it a cruel burden to choose to live here. I State Comptroller expectations for increased state income. that businesses will want to move to without love New York and will fight to save it from Thomas DiNapoli’s Now pile on one time savings gimmicks of a complete purge of every incumbent going the way of Greece. It will take 230 new a s s e s s m e n t over $14 billion instead of truly occupying a seat in the current Citizen Legislators, dedicated to cutting of the $134.4 cutting costs ANYWHERE legislature. It is humiliating that the size of government and government billion budgetary within the State government. Guest we have allowed these people to spending, dedicated to making New York a b e h e m o t h .