Temporality and the Anthropocene in Contemporary Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV Johanna Lecklin English

JOHANNA LECKLIN www.johannalecklin.com [email protected] EDUCATION 2018 PhD, Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, Finland, disputation in November 2008 MA, Art History, Helsinki University, Finland 2003 MFA, Fine Art Media, Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, Finland 1999 BFA, Painting Department, Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, Finland 1998-99 Slade School of Fine Art, Fine Art Media, UCL, Erasmus exchange, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Galleria Heino, Helsinki 2017 Mediabox, Forum Box, Helsinki, Finland 2014-15 The Cage, Rappu Space, Pori Art Museum, Pori, Finland 2013 The Cage, Gallery Forum Box, Helsinki, Finland 2012 Language Is the Key to Everything, Haninge Art Hall, Haninge, Sweden 2012 Your Songs Transport Me to A Place I’ve Never Been, Galleri Sinne, Helsinki, Finland 2011 Story Café, Suomesta Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2009 Hitwoman, Heino Gallery, Helsinki, Finland 2007 Tomorrow, Photographic Gallery Hippolyte, Helsinki, Finland Story Café, Linnagallerii, part of the Young Artists’ Biennale, Tallinn, Estonia The Boxer and the Ballerina, Helsinki Kunsthalle, Studio, Helsinki, Finland 2006 Story Café, Galleria Huuto Uudenmaankatu, Helsinki, Finland 2005 There Is A Lot of Joy, Too, Gallery Heino, Helsinki, Finland 2004 A Few Nightmares, Kluuvi Gallery, Helsinki Art Museum, Helsinki, Finland 2003 Portraits of Everyday Life, Photographic Gallery Hippolyte, Helsinki, Finland 2002 Safe and Exciting, Cable Gallery, Helsinki, Finland 2001 A Sensible Use Of Time, Kluuvi Gallery, Helsinki Art Museum, Helsinki, Finland SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 FOKUS Festival, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, Denmark 2017 Self-portrait in Time, Helsinki Kunsthalle, Finland 2017 Visible Country, Arktikum, Rovaniemi, Finland 2016 Eternal Mirror, group exhibition, Gallery Ama, Helsinki, Finland 2016 UN/SAFE, Kuntsi Museum of Modern Art, Vaasa, Finland 2015-16 Face to Face. -

International Evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery

International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Publications of the Ministry on Education and Culture, Finland 2011:18 International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Publications of the Ministry on Education and Culture, Finland 2011:18 Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö • Kulttuuri-, liikunta- ja nuorisopolitiikan osasto • 2011 Ministry of Education and Culture• Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy • 2011 Ministry of Education and Culture Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy Meritullinkatu 10, Helsinki P.O. Box 29, FIN-00023 Government Finland www.minedu.fi/minedu/publications/index.html Layout: Timo Jaakola ISBN 978-952-263--045-2 (PDF) ISSN-L 1799-0327 ISSN 1799-0335 (Online) Reports of the Ministry of Education and Culture 2011:18 Kuvailulehti Julkaisija Julkaisun päivämäärä Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö 15.4.2011 Tekijät (toimielimestä: toimielimen nimi, puheenjohtaja, sihteeri) Julkaisun laji Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön Kansainvälinen arviointipaneeli: projektipäällikkö Sune Nordgren työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä (pj.) Dr. Prof. Günther Schauerte, johtaja Lene Floris, ja Toimeksiantaja Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö oikeustieteen tohtori Timo Viherkenttä. Sihteeri: erikoissuunnittelija Teijamari Jyrkkiö Toimielimen asettamispvm Dnro 23.6.2010 66/040/2010 Julkaisun nimi (myös ruotsinkielinen) International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Julkaisun osat Muistio ja liitteet Tiivistelmä Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö päätti arvioida Valtion taidemuseon toiminnan vuonna 2010. Valtion taidemuseo on ollut valtion virasto vuodesta 1990 lähtien ja sen muodostavat Ateneumin taidemuseo, Nykytaiteen museo Kiasma, Sinebrychoffin taidemuseo ja Kuvataiteen keskusarkisto. Tulosohjattavan laitoksen tukitoimintoja hoitavat konservointilaitos, koko maan taidemuseoalan kehittämisyksikkö sekä hallinto- ja palveluyksikkö. Organisaatiorakenne on pysynyt suurinpiirtein samanlaisena sen koko olemassaolon ajan. Taidemuseon vuosittainen toimintamääräraha valtion budjetissa on n. 19 miljoonaa euroa ja henkilötyövuosia on n. -

Christmas and New Year.2019

OPENING HOURS Mon Tue Wed Thurs Tue Wed Mon CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR 2019 23.12. 24.12. 25.12. 26.12. 31.12. 1.1. 6.1. ART MUSEUMS Amos Rex - - - 11-17 - - 11-18 Ateneum Art Museum - - - 10-17 10-17 - - Didrichsen Art Museum - - - 11-18 11-18 11-18 - Free entry 26.-29.12. Gallen-Kallela museum - - 11-17 11-17 11-16 11-17 11-17 HAM – Helsinki Art Museum (Tennispalace) - - - 11-19 11-17 - - Kunsthalle Helsinki - - - 11-17 - - - Kiasma, Contemporary Art Museum - - - 10-17 10-17 - - WeeGee building + EMMA – Espoo museum of - - - 11-17 - - - modern art Sinebrychoff Art Museum - - - 10-17 10-17 10-17 - HISTORICAL MUSEUMS Helsinki City Museums: -Helsinki City Museum - - - - 11-15 - - -Hakasalmi Villa - - - - 11-15 - - -Tram Museum - - - - 11-15 - - -Burgher’s House - - - - - - 11-17 Mannerheim museum - - - - - - - National Museum of Finland - - - 11-18 11-18 - - Urho Kekkonen Museum, Tamminiemi - - - - - - - CABLE FACTORY Hotel and Restaurant Museum - - - - - - - Theatre Museum - - - - - - - Finnish Museum of Photography - - - - - - - OTHER MUSEUMS Alvar Aalto Studio (Riihitie 20), only open for guided tours - - - 11.30 11.30 11.30 - House (Tiilimäki 20), only open for guided tours - - - 13 13 13, 14, 15 13, 14, 15 Design Museum - - - - 11-15 - - Lab & Design Museum Arabia - - - - - - - Iittala & Arabia Design Centre Store 10-20 10-13 - - 10-18 - 10-16 Helsinki University Museum - - - - - - - Closed 23.12.2019-6.1.2020 Natural History Museum - - - - - - - Helsinki Observatory - - - - - - - Päivälehti-press museum 11-17 - - - 11-17 - 11-17 Seurasaari Open Air Museum opens - - - - - - 15.5.2019 Museum of Finnish Architecture - - - - 11-16 - - Sports Museum of Finland opens in - - - - - - 2020 Museum of Technology - - - - - - - Helsinki Tourist Information, Helsinki Marketing 12/2019 Helsinki Marketing is not responsible for any changes OPENING HOURS Mon Tue Wed Thurs Tue Wed Mon CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR 2019 23.12. -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

Imaging the Spiritual Quest Spiritual the Imaging

WRITINGS FROM THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 06 Imagingthe Spiritual Quest Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality FRANK BRÜMMEL & GRANT WHITE, EDS. Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality WRITINGS FROM THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 06 Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality FRANK BRÜMMEL & GRANT WHITE, EDS. Table of Contents Editors and Contributors 7 Acknowledgements 12 Imaging the Spiritual Quest Introduction 13 Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality. GRANT WHITE Writings from the Academy of Fine Arts (6). Breathing, Connecting: Art as a Practice of Life 19 Published by RIIKKA STEWEN The Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki The Full House and the Empty: On Two Sacral Spaces 33 Editors JYRKI SIUKONEN Frank Brümmel, Grant White In a Space between Spirituality and Religion: Graphic Design Art and Artists in These Times 41 Marjo Malin GRANT WHITE Printed by Mutual Reflections of Art and Religion 53 Grano Oy, Vaasa, 2018 JUHA-HEIKKI TIHINEN Use of Images in Eastern and Western Church Art 63 ISBN 978-952-7131-47-3 JOHAN BASTUBACKA ISBN 978-952-7131-48-0 pdf ISSN 2242-0142 Funerary Memorials and Cultures of Death in Finland 99 © The Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki and the authors LIISA LINDGREN Editors and Contributors Stowaway 119 PÄIVIKKI KALLIO On Prayer and Work: Thoughts from a Visit Editors to the Valamo Monastery in Ladoga 131 ELINA MERENMIES Frank Brümmel is an artist and university lecturer. In his ar- tistic practice Brümmel explores how words, texts and im- “Things the Mind Already Knows” ages carved onto stone semiotically develop meanings and and the Sound Observer 143 narratives. -

HELSINKI the Finnish Capital of Helsinki Is a Modern City with Over Half a Million Residents and Is Situated on the Baltic Sea

HELSINKI The Finnish capital of Helsinki is a modern city with over half a million residents and is situated on the Baltic Sea. The city is known for its great mixture of neo-classical buildings, orthodox style churches and its chique bar and restaurant scene. The archipelago that surrounds Helsinki with hundreds of tiny islands creates an idyllic environment for cruises. Some of our favorite hotel picks in Helsinki Sightseeing in Helsinki Helsinki Cathedral - You can’t miss this large white church with a green top. This neoclassical style church is a one most known landmark of Helsinki. Located at the Senaatintori. Akateeminen Kirjakauppa - The Akademic book shop, de- signed by Finland’s most Famous architect Alvar Aalto in 1969. Situated at Pohjoisesplanadi 39, just next to Stock- mann department store (Finland’s version of Harrods). Kiasma - Museum of Contemporary Art. It’s situated close to the main railway station and is easy to get to. Image Credits: Visit Finland Well worth a visit! Address: Mannerheiminaukio 2, 00100 Helsinki. The Church Inside a Rock – “Temppeliaukion kirkko” located at Lutherinkatu 3. To experience something a bit different a visit to this fascinating church is something you can’t miss. It’s one of Helsinki’s most popular tourist From the airport attractions, and while you wander around this church Bus – Helsinki-Vantaa Airport is located 20 km north of the built inside a giant block of natural granite, you’ll under- city centre of Helsinki. The Finnair City bus runs frequently stand why. between the airport and city. The bus trip takes around 30 minutes. -

A Life in Theater

22 19 – 25 JANUARY 2012 WHERE TO GO HELSINKI TIMES Wed 25 January Kunsthalle Helsinki Greystone Nervanderinkatu 3 Psychedelic garage rock. Tue, Thu, Fri 11:00-18:00 Bar Loose Wed 11:00-20:00 Annankatu 21 Sat-Sun 11:00-17:00 ANTON VERHO Tickets €5/6 Tickets €0/5.50/8 www.barloose.com www.taidehalli.fi Wed 25 January Until Sun 29 January In the mood for love Ana Popovic (SRB) Juhani Linnovaara – The Power Spring season at Zodiak starts in romantic mood, as new dance Brilliant blues. of Fantasy Tavastia Retrospective exhibition of an artist piece The Greatest Love Songs, directed by dancer and perfor- Urho Kekkosen katu 4-6 with a distinctive visual world of his mance artist Maija Mustonen, premieres on Thursday 19 January. Tickets €20/22 own, includes paintings, graphics, Inspired by a nostalgic finding from the attic – a tape featuring www.tavastiaklubi.fi sculptures and jewellery. love songs from artists such as Elton John, Marvin Gaye and The Didrichsen Museum of Art Bangles – the author created a piece that is wildly melodramat- Wed 25 January and Culture Eva & Manu (FIN/FRA) Kuusilahdenkuja 1 ic, yet also sincerely intimate and highly personal. Sympathetic folk pop duo. Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00 The performance is a sweet-scented dance cavalcade portray- Semifinal Tickets €3/7/9 ing the great love stories of the century – tales of heartbreak, Urho Kekkosen katu 4-6 www.didrichsenmuseum.fi jealousy and romantic fulfilment. The Greatest Love Songs con- Tickets €5/6 www.semifinal.fi Until Sun 29 January sists of ten mini-choreographies, with each dancer interpreting Anssi Kasitonni a love song with a personal meaning to them. -

Arrive in Copenhagen Itinerary for Best of Scandinavia & the Baltics • Expat Explore Start Point

Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:38:42 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/21 Itinerary for Best of Scandinavia & the Baltics • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Park Inn by Radisson Copenhagen Radisson Blu Sobieski Hotel, Airport, plac Artura Zawiszy 1, 02-025 Warszawa, Engvej 171, 2300 København, Denmark | Tel: Poland 0045 32 87 02 02 10:00 hrs 10:00 hrs DAY 1: Arrive in Copenhagen Welcome to Copenhagen! Today is the beginning of this exciting Best of Scandinavia and the Baltics tour! Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark’s capital city and check into the hotel. This afternoon, meet up with your tour leader and the rest of the tour group. Once everybody has arrived, it’s time to head off on an exciting city tour of Copenhagen with an expert local guide! Complete the first day of the tour with an included group dinner this evening and get to know more about your tour leader and fellow travellers. Adventure definitely awaits over the next 20 days! Experiences Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:38:42 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/21 Guided tour of Copenhagen: Embark on a walking and driving tour of Copenhagen with a local guide. Highlights of the tour include the well-known Nyhavn Waterfront, Rosenborg, the Town Hall, Amalienborg Palace and the Little Mermaid statue. Included Meals Accommodation Breakfast: Lunch: Dinner: Park Inn Copenhagen Airport DAY 2: Copenhagen: Free Day Explore Copenhagen at your leisure during the free day today! Copenhagen is a colourful and creative city, home to ornate royal palaces and modernist buildings. -

Helsinki! Helsinki Is Simply So Unbelievably Lovable Right Now

WELCOME TO THE CITY WHERE HEAVEN MEETS THE SEA - HELSINKI! HELSINKI IS SIMPLY SO UNBELIEVABLY LOVABLE RIGHT NOW. IT FEELS LIBERATED, HAPPY, INSPIRED, CREATIVE AND BOLD. IT’S AS IF THE LOCALS HAVE ALL GOT TOGETHER AND DECIDED TO SHOW THE WORLD AT LAST WHAT HELSINKI IS MADE OF! #VISITHELSINKI Helsinki Programme, 5.5.2016 THURSDAY 5.5. 9.45 MEET UP AT RAILWAY SQUARE The tour starts from Mikonkatu 17, in front of the Casino Helsinki. 10.00 TRAM TOUR AROUND HELSINKI The guided tour will cover the main sights and attractions of Helsinki, eg. the beautiful harbor area with the legendary Market Square, neoclassical Senate Square, Art Nouveau and contemporary architecture such as Kiasma. You’ll also have a look at the brand new Jätkäsaari district currently under construction on a southern peninsula recently vacated by a cargo port. Architect and Head of Project Mr Matti Kaijansinkko from the City Planning Department will introduce you to Jätkäsaari. Mr Ollipekka Heikkilä, Head of Development, Helsinki City Transport will tell you all want to know about the new custom built Artic tram. http://en.uuttahelsinkia.fi/jatkasaari CONTACT DETAILS FOR VISIT HELSINKI Tel: +358 (0)9 310 25 215 [email protected] www.facebook.com/visithelsinki @visithelsinki #VisitHelsinki 11.30 BOAT RIDE TO SUOMENLINNA MARITIME FORTRESS 12.00 LUNCH AT VALIMO The café-restaurant of Suomenlinna’s guest harbour is a popular lunch and evening spot for both yachts people and the residents of Suomenlinna. The restaurant is located in the dock area and its menu includes various types of soups, pasta and salads. -

Welcomes Cruise Visitors

ENGLISH Welcomes Cruise Visitors Vibrant and urban Helsinki is a unique and diverse city, where traditional Eastern exotica meets contemporary Scandinavian style. Helsinki is also a youthful and relaxed city where cosmopoli- tan lifestyle exists in perfect harmony with nature. This second-most northern capital city in the world is full of unique experiences and friendly people who speak good English. Finland’s capital offers lots to see, do and experience for cruise visitors of all ages. Most sights and attractions are within walking distance and getting around is easy. MAP & DISCOUNTS INCLUDED MUST SEE ATTRACTIONS Temppeliaukio Church Museum of Contemporary Quarried out of the natural bed- Art, Kiasma The Helsinki Cathedral and rock, Temppeliaukio Church is one Kiasma presents three major new the Senate Square of Helsinki’s most popular tourist exhibitions every year alongside The beautiful and historically signif- attractions. numerous smaller projects. The icant Helsinki Cathedral is for many programme includes exhibitions of the symbol of Helsinki. The Senate Finnish and international art and Square and its surroundings form thematic group exhibitions. a unique and cohesive example of Neoclassical architecture. Uspenski cathedral Completed in 1868 in the Kataja- nokka district of Helsinki, Uspenski is the largest Orthodox cathedral in The National Museum of Finland Olympic Stadium & Stadium Tower Western Europe. The redbrick edi- The museum’s main exhibitions The Olympic Stadium is one of the ½FHFRPELQHV(DVWHUQDQG:HVWHUQ present Finnish life from prehis- most famous landmarks in Helsin- LQ¾XHQFHV toric times to the present. ki. The stadium tower is 72 metres high and offers a spectacular view over Helsinki. -

Press Release 29.8.2018

Press release, 29 August 2018 Facilities for new services at Finlandia Hall to be built during renovation Plans are in place for an audio-visual exhibition, design store, and a drink bar on the roof The renovation project of Finlandia Hall will begin in 2021 according to the preliminary schedule. The project means not only restoration of existing premises but also construction of a framework for new services. Plans for the renewed Finlandia Hall include, for instance, an audio-visual exhibition and a design store. The kitchen will be modernized so the restaurant can be of service during large events and conferences in the future. Restaurant operations will be developed so that people from far away arrive at Finlandia Hall for dinner. A drink bar on the rooftop terrace is planned as a main attraction. For the area around Töölönlahti Bay, there are plans for glamping-type activity that connects Finlandia Hall more closely to the surrounding park area. Finlandia Hall is the largest and best-known event and conference centre in Finland. The building’s turnover has doubled in six years, and Finlandia Hall Ltd’s operation is profitable. – Finlandia Hall is very important for Helsinki both as an architectural landmark and as a living conference centre, which enables the arrangement of diverse events in the capital city of Finland. This is why special care must be taken of the building. Every year Finlandia Hall welcomes more than 200,000 visitors. According to one study, they spend almost €50 million per year on various experiences, shopping and services in Helsinki, says Anni Sinnemäki, the Deputy Mayor for Urban Environment. -

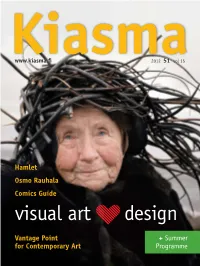

Visual Art Design

www.kiasma.fi 2012 51 vol 15 Hamlet Osmo Rauhala Comics Guide visual art design Vantage Point + Summer for Contemporary Art Programme Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma Is a JANITOOM; FNG / CAA / PIRJE MYKKÄNEN, PETRI SUMMANEN,TERO SUVILAMMI, PETRIVIRTANEN Vantage Point Kiasma is an oasis of contemporary art and visual culture in the heart of Helsinki. Surrounded by the bustle of urban life and flanked by the Postitalo, Parliament and Lasipalatsi buildings and the Helsinki Music Centre, the shimmering aluminium-clad art museum has in a short time earned kiasma its place at the summit of the most talked-about cultural life in Finland. 2 Kiasma Kiasma 3 Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art 1. LAURI ERIKSSON 2. AKI-PEKKA SINIKOSKI 3. JUHA SAARINEN 4. FNG / CAA PETRI VIRTANEN 5. JANNE HEINONEN 6. FNG / CAA PIRJE MYKKÄNEN 7. VIRTANEN 3. JUHA SAARINEN 4. FNG / CAA PETRI ERIKSSON 2. AKI-PEKKA SINIKOSKI 1. LAURI AS A MUSEUM OF contemporary and street dust. The next thing Minna Koivurinta, Riitta Lindegren, Teppo Rantanen The most impressive is the tall, art, Kiasma is the place where to go that comes to mind is the narrow Partner, Advertising Freelance Journalist, CEO, asymmetric main gallery on the top to see the very latest in art. While resource framework of museums Agency Satumaa Writer Deloitte floor, which must be also one of the showcasing Finnish and international today, which means that Kiasma too most challenging for exhibitions. art in its exhibitions, Kiasma also is associated with many unfulfilled 3. The café. 1. Kiasma is of course the only 1.