10Th Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Perspective on Interactions Between Police and Persons with Mental Disabilities Michael L

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 43 Number 3 Mental Health, the Law, & the Urban Article 5 Environment 2016 "Had to Be Held Down by Big Police": A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Perspective on Interactions Between Police and Persons with Mental Disabilities Michael L. Perlin Alison J. Lynch Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Recommended Citation Michael L. Perlin and Alison J. Lynch, "Had to Be Held Down by Big Police": A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Perspective on Interactions Between Police and Persons with Mental Disabilities, 43 Fordham Urb. L.J. 685 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol43/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “HAD TO BE HELD DOWN BY BIG POLICE”: A THERAPEUTIC JURISPRUDENCE PERSPECTIVE ON INTERACTIONS BETWEEN POLICE AND PERSONS WITH MENTAL DISABILITIES Michael L. Perlin, Esq.* & Alison J. Lynch, Esq.** Introduction ............................................................................................. 685 I. Current State of Affairs ................................................................... 696 II. Therapeutic Jurisprudence ............................................................. 701 A. What Is Therapeutic Jurisprudence? ................................. -

Constitutional Jurisprudence of History and Natural Law: Complementary Or Rival Modes of Discourse?

California Western Law Review Volume 24 Number 2 Bicentennial Constitutional and Legal Article 6 History Symposium 1988 Constitutional Jurisprudence of History and Natural Law: Complementary or Rival Modes of Discourse? C.M.A. McCauliff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr Recommended Citation McCauliff, C.M.A. (1988) "Constitutional Jurisprudence of History and Natural Law: Complementary or Rival Modes of Discourse?," California Western Law Review: Vol. 24 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol24/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Western Law Review by an authorized editor of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McCauliff: Constitutional Jurisprudence of History and Natural Law: Compleme Constitutional Jurisprudence of History and Natural Law: Complementary or Rival Modes of Discourse? C.M.A. MCCAULIFF* The Bill of Rights provides broadly conceived guarantees which invite specific judicial interpretation to clarify the purpose, scope and meaning of particular constitutional safeguards. Two time- honored but apparently divergent approaches to the jurisprudence of constitutional interpretation have been employed in recent first amendment cases: first, history has received prominent attention from former Chief Justice Burger in open-trial, family and reli- gion cases; second, natural law has been invoked by Justice Bren- nan in the course of responding to the Chief Justice's historical interpretation. History, although indirectly stating constitutional values, provides the closest expression of the Chief Justice's own jurisprudence and political philosophy. -

Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: the Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 27 Issue 5 Article 7 1982 Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles James McClellan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation James McClellan, Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles, 27 Vill. L. Rev. 1019 (1982). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol27/iss5/7 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McClellan: Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect 1981-82] CONGRESSIONAL RETRACTION OF FEDERAL COURT JURISDICTION TO PROTECT THE RESERVED POWERS OF THE STATES: THE HELMS PRAYER BILL AND A RETURN TO FIRST PRINCIPLES JAMES MCCLELLAN t S INCE THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THE WARREN COURT, countless bills have been introduced in Congress which would deny the federal courts jurisdiction over a great variety of subjects ranging from busing to abortion.' The exceptions clause of article III of the Constitution provides Congress with the authority to enact such bills. 2 While none of these proposed bills has been enacted into law, it is noteworthy that two have passed at least one house of Congress, and that both of these have sought to deny all federal courts, including the Supreme Court, jurisdiction over certain cases arising under the fourteenth amendment. -

Three Federalisms Randy E

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2007 Three Federalisms Randy E. Barnett Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/23 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers THREE FEDERALISMS RANDY E. BARNETT* ABSTRACT: Debates over the importance of “federalism” are often obscured by the fact that there are not one, but three distinct versions of constitutional federalism that have arisen since the Founding: Enumerated Powers Federalism in the Founding era, Fundamental Rights Federalism in the Reconstruction era, and Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism in the post-New Deal era. In this very short essay, my objective is to reduce confusion about federalism by defining and identifying the origin of each of these different conceptions of federalism. I also suggest that, while Fundamental Rights Federalism significantly qualified Enumerated Powers Federalism, it was not until the New Deal’s expansion of federal power that Enumerated Powers Federalism was eviscerated altogether. To preserve some semblance of state discretionary power in the post-New Deal era, the Rehnquist Court developed an ahistorical Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism that was both under- and over-inclusive of the role of federalism that is warranted by the original meaning of the Constitution as amended. In my remarks this morning, I want to explain how there are, not one, but three distinct versions of federalism that have developed since the Founding. -

Predictive POLICING the Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations

Safety and Justice Program CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Safety and Justice Program View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that ad- dress the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Safety and Justice Program PREDICTIVE POLICING The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations Walter L. -

History SS Federalism Today Complex Project

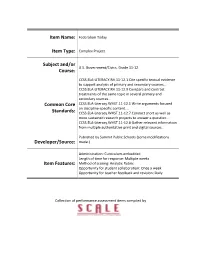

Item Name: Federalism Today Item Type: Complex Project Subject and/or U.S. Government/Civics, Grade 11-12 Course: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources… CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources… Common Core CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content…. Standards: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.7 Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question… CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources… Published by Summit Public Schools (some modifications Developer/Source: made.) Administration: Curriculum-embedded Length of time for response: Multiple weeks Item Features: Method of scoring: Analytic Rubric Opportunity for student collaboration: Once a week Opportunity for teacher feedback and revision: Daily Collection of performance assessment items compiled by Overview This learning module will prepare you to write an argument over which level of government, federal or state, should have the authority and power when making and executing laws on controversial issues. You will research an issue of your choice, write an argument in support of your position, and then present it to a panel of judges. Standards AP Standards: APS.SOC.9-12.I Constitutional Underpinnings of United States Government APS.SOC.9-12.I.D - Federalism Objective: Understand the implication(s) -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

Federalism in the Constitution

Federalism in the Constitution As you read each paragraph, answer the questions in the margin. The United States is one country—but it’s also a bunch of states. You When creating the Constitution, what could almost say it’s a group of states that are, well, united. When we things did we need our central created the Articles of Confederation, each state already had its own government to be able to do? government and court system, so the new Americans weren’t exactly running amok. But if the new United States was going to be able to deal with other nations, it needed one government that would speak for the entire country. It also needed one central government to do things like declare war on other countries, keep a military, and negotiate treaties with other countries. There also needed to be federal courts where citizens from different states could resolve their disputes. So, the Founders created the Constitution to do those things. Define federalism. The United States Constitution created a central government known as the federal government. The federal government deals with issues that affect the entire country. Each state also has its own state government that only handles the affairs of that state. This division of power between a central government and state governments is called federalism. The federal government gets all of its power from the Create a Venn Diagram, with labels, that shows Constitution. These federal powers are listed in the the relationship between the federal powers, Constitution. In order to keep the federal government from reserve powers, and concurrent powers. -

Seattle Police Department

Seattle Police Department Adrian Diaz, Interim Chief of Police (206) 684-5577 http://www.seattle.gov/police/ Department Overview The Seattle Police Department (SPD) addresses crime, enforces laws, and enhances public safety by delivering respectful, professional, and dependable police services. SPD divides operations into five precincts. These precincts define east, west, north, south, and southwest patrol areas, with a police station in each area. The department's organizational model places neighborhood-based emergency response services at its core, allowing SPD the greatest flexibility in managing public safety. Under this model, neighborhood-based personnel in each precinct assume responsibility for public safety management, primary crime prevention and law enforcement. Precinct-based detectives investigate property crimes and crimes involving juveniles, whereas detectives in centralized units located at SPD headquarters downtown and elsewhere conduct follow-up investigations into other types of crimes. Other parts of the department function to train, equip, and provide policy guidance, human resources, communications, and technology support to those delivering direct services to the public. Interim Police Chief Adrian Diaz has committed the department to five focus areas to anchor itself throughout the on-going work around the future of community safety: • Re-envisioning Policing - Engage openly in a community-led process of designing the role the department should play in community safety • Humanization - Prioritize the sanctity -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

Constitution of the United States of America—17871

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA—1787 1 WE THE PEOPLE of the United States, in Order to SECTION. 2. 1 The House of Representatives form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, shall be composed of Members chosen every sec- insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the ond Year by the People of the several States, common defence, promote the general Welfare, and the Electors in each State shall have the and secure the Blessings of Liberty to our- Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most selves and our Posterity, do ordain and estab- numerous Branch of the State Legislature. lish this Constitution for the United States of 2 No Person shall be a Representative who America. shall not have attained to the Age of twenty five Years, and been seven Years a Citizen of the ARTICLE. I. United States, and who shall not, when elected, SECTION 1. All legislative Powers herein grant- be an Inhabitant of that State in which he shall ed shall be vested in a Congress of the United be chosen. States, which shall consist of a Senate and 3 Representatives and direct Taxes shall be ap- House of Representatives. portioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be deter- 1 This text of the Constitution follows the engrossed copy signed by Gen. Washington and the deputies from 12 States. The mined by adding to the whole Number of free small superior figures preceding the paragraphs designate Persons, including those bound to Service for a clauses, and were not in the original and have no reference to Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, footnotes. -

2020 Annual Report MISSION in Support of the Port of Seattle’S Mission, We: • Fight Crime, • Protect and Serve Our Community

PORT OF SEATTLE POLICE 2020 Annual Report MISSION In support of the Port of Seattle’s Mission, we: • fight crime, • protect and serve our community. VISION To be the nation’s finest port police. GUIDING PRINCIPLES • Leadership • Integrity • Accountability Port of Seattle Commissioners and Executive Staff: It is my pleasure to present to you the 2020 Port of Seattle Police Department Annual Report. This past year was challenging in unprecedented ways. COVID-19 significantly impacted our day-to-day operations and our employees and their families. National civil unrest and demand for police reform led to critique and an ongoing assessment of the department. Changes in leadership, ten retirements, and a hiring freeze compounded the pressures and stress on your Police Department members. However, despite these challenges, I am proud to say that the high caliber professionals in the department stepped up. They adapted to the new environment and continued to faithfully perform their mission to fight crime, and protect and serve our community. Port employees, business partners, travelers, and visitors remained safe yet another year, because of the teamwork and outstanding dedication of the people who serve in your Police Department. As you read the pages to follow, I hope you enjoy learning more about this extraordinary team. On behalf of the exemplary men and women of this Department, it has been a pleasure to serve the Port of Seattle community. - Mike Villa, Deputy Chief Table of Contents Command Team . 6 Jurisdiction .........................................7 Community Engagement ...........................8 Honor Guard .......................................9 Operations Bureau .................................10 Port of Seattle Seaport . 11 Marine Patrol Unit .................................12 Dive Team .........................................12 SEA Airport .