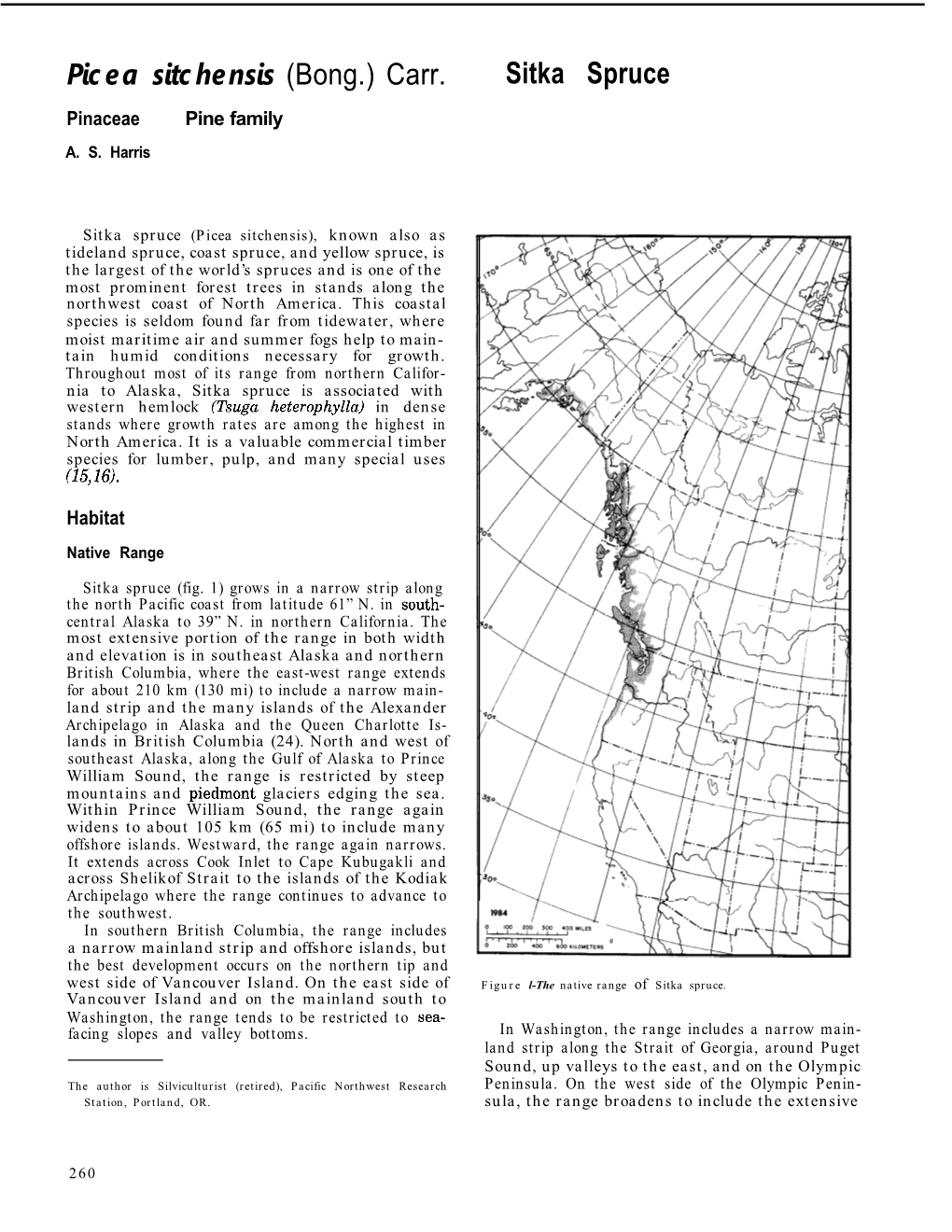

Picea Sitchensis (Bong.) Carr. Sitka Spruce Pinaceae Pine Family A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEFOLIATORS Insect Sections

Alaska. Reference is made to this map in selected DEFOLIATORS insect sections. (Precipitation information from Schwartz, F.K., and Miller, J.F. 1983. Probable maximum precipitation and snowmelt criteria for Fewer defoliator plots (27 plots) were visited during southeast Alaska: National Weather Service the 1999 aerial survey than in previous years (52 plots) Hydrometeorological Report No. 54. 115p. GIS layer throughout southeast Alaska. An effort was made to created by: Tim Brabets, 1997. distribute these plots evenly across the archipelago. URL:http://agdc.usgs.gov/data/usgs/water) The objectives during the 1999 season were to: ¨ Spend more time covering the landscape during Spruce Needle Aphid the aerial survey, Elatobium abietinum Walker ¨ Allow more time to land and identify unknown mortality and defoliation, and Spruce needle aphids feed on older needles of Sitka ¨ Avoid visit sites that were hard to get to and had spruce, often causing significant amounts of needle few western hemlocks. drop (defoliation). Defoliation by aphids cause reduced tree growth and can predispose the host to Hemlock sawfly and black-headed budworm larvae other mortality agents, such as the spruce beetle. counts were generally low in 1999 as they were in Severe cases of defoliation alone may result in tree 1998. The highest sawfly larvae counts were from the mortality. Spruce in urban settings and along marine plots in Thorne Bay and Kendrick Bay, Prince of shorelines are most seriously impacted. Spruce aphids Wales Island. Larval counts are used as a predictive feed primarily in the lower, innermost portions of tree tool for outbreaks of defoliators. For example, if the crowns, but may impact entire crowns during larval sample is substantially greater in 1999, then an outbreaks. -

Biodiversity Climate Change Impacts Report Card Technical Paper 12. the Impact of Climate Change on Biological Phenology In

Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Biodiversity Climate Change impacts report card technical paper 12. The impact of climate change on biological phenology in the UK Tim Sparks1 & Humphrey Crick2 1 Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, CV1 5FB 2 Natural England, Eastbrook, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8DR Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Executive summary Phenology can be described as the study of the timing of recurring natural events. The UK has a long history of phenological recording, particularly of first and last dates, but systematic national recording schemes are able to provide information on the distributions of events. The majority of data concern spring phenology, autumn phenology is relatively under-recorded. The UK is not usually water-limited in spring and therefore the major driver of the timing of life cycles (phenology) in the UK is temperature [H]. Phenological responses to temperature vary between species [H] but climate change remains the major driver of changed phenology [M]. For some species, other factors may also be important, such as soil biota, nutrients and daylength [M]. Wherever data is collected the majority of evidence suggests that spring events have advanced [H]. Thus, data show advances in the timing of bird spring migration [H], short distance migrants responding more than long-distance migrants [H], of egg laying in birds [H], in the flowering and leafing of plants[H] (although annual species may be more responsive than perennial species [L]), in the emergence dates of various invertebrates (butterflies [H], moths [M], aphids [H], dragonflies [M], hoverflies [L], carabid beetles [M]), in the migration [M] and breeding [M] of amphibians, in the fruiting of spring fungi [M], in freshwater fish migration [L] and spawning [L], in freshwater plankton [M], in the breeding activity among ruminant mammals [L] and the questing behaviour of ticks [L]. -

Respacing Naturally Regenerating Sitka Spruce and Other Conifers

Respacing naturally regenerating Sitka spruce and other conifers Sitka spruce ( Picea sitchensis ) Practice Note Bill Mason December 2010 Dense natural regeneration of Sitka spruce and other conifers is an increasingly common feature of both recently clearfelled sites and stands managed under continuous cover forestry in upland forests of the British Isles. This regeneration can be managed by combining natural self-thinning in the early stages of stand establishment with management intervention to cut access racks and carry out selective respacing to favour the best quality trees. The target density should be about 2000 –2500 stems per hectare in young regeneration or on windfirm sites where thinning will take place. On less stable sites that are unlikely to be thinned, a single intervention to a target density of 1750 –2000 stems per hectare should improve mean tree diameter without compromising timber quality. Managing natural regeneration in continuous cover forestry or mixed stands can be based upon similar principles but the growth of the regenerated trees will be more variable. FCPN016 1 Introduction Natural self-thinning Dense natural regeneration of conifers in upland Britain has Management intervention to respace young trees is sometimes become increasingly common as forests planted during the last justified on the basis that stands of dense natural regeneration century reach maturity. The density of naturally regenerated Sitka will ‘stagnate’ if no respacing is carried out. However, with the spruce ( Picea sitchensis ) can exceed 100 000 seedlings per hectare exception of stands of lodgepole pine ( Pinus contorta ) on very on suitable sites in forests throughout northern and western poor-quality sites in Canada, there are few examples of Britain – examples include Fernworthy, Glasfynydd, Radnor, ‘stagnation’ occurring. -

The Green Spruce Aphid in Western Europe

Forestry Commission The Green Spruce Aphid in Western Europe: Ecology, Status, Impacts and Prospects for Management Edited by Keith R. Day, Gudmundur Halldorsson, Susanne Harding and Nigel A. Straw Forestry Commission ARCHIVE Technical Paper & f FORESTRY COMMISSION TECHNICAL PAPER 24 The Green Spruce Aphid in Western Europe: Ecology, Status, Impacts and Prospects for Management A research initiative undertaken through European Community Concerted Action AIR3-CT94-1883 with the co-operation of European Communities Directorate-General XII Science Research and Development (Agro-Industrial Research) Edited by Keith R. t)ay‘, Gudmundur Halldorssorr, Susanne Harding3 and Nigel A. Straw4 ' University of Ulster, School of Environmental Studies, Coleraine BT52 ISA, Northern Ireland, U.K. 2 2 Iceland Forest Research Station, Mogilsa, 270 Mossfellsbaer, Iceland 3 Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Department of Ecology and Molecular Biology, Thorvaldsenvej 40, Copenhagen, 1871 Frederiksberg C., Denmark 4 Forest Research, Alice Holt Lodge, Wrecclesham, Farnham, Surrey GU10 4LH, U.K. KVL & Iceland forestry m research station Forest Research FORESTRY COMMISSION, EDINBURGH © Crown copyright 1998 First published 1998 ISBN 0 85538 354 2 FDC 145.7:453:(4) KEYWORDS: Biological control, Elatobium , Entomology, Forestry, Forest Management, Insect pests, Picea, Population dynamics, Spruce, Tree breeding Enquiries relating to this publication should be addressed to: The Research Communications Officer Forest Research Alice Holt Lodge Wrecclesham, Farnham Surrey GU10 4LH Front Cover: The green spruce aphid Elatobium abietinum. (Photo: G. Halldorsson) Back Cover: Distribution of the green spruce aphid. CONTENTS Page List of contributors IV Preface 1. Origins and background to the green spruce aphid C. I. Carter and G. Hallddrsson in Europe 2. -

Isoenzyme Identification of Picea Glauca, P. Sitchensis, and P. Lutzii Populations1

BOT.GAZ. 138(4): 512-521. 1977. (h) 1977 by The Universityof Chicago.All rightsreserved. ISOENZYME IDENTIFICATION OF PICEA GLAUCA, P. SITCHENSIS, AND P. LUTZII POPULATIONS1 DONALD L. COPES AND ROY C. BECKWITH USDA Forest Service,Pacific Northwest Forest and Range ExperimentStation ForestrySciences Laboratory, Corvalli.s, Oregon 97331 Electrophoretictechniques were used to identify stands of pure Sitka sprucePicea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.and purewhite spruceP. glauca (Moench)Voss and sprucestands in whichintrogressive hybridization betweenthe white and Sitka sprucehad occurred.Thirteen heteromorphic isoenzymes of LAP, GDH, and TO were the criteriafor stand identification.Estimates of likenessor similaritybetween seed-source areas were made from 1) determinationsIntrogressed hybrid stands had isoenzymefrequencies that were in- termediatebetween the two purespecies, but the seedlingswere somewhat more like white sprucethan like Sitkaspruce. Much of the west side of the KenaiPeninsula appeared to be a hybridswarm area, with stands containingboth Sitka and white sprucegenes. The presenceof white sprucegenes in Sitka sprucepopula- tions was most easily detectedby the presenceof TO activity at Rm .52. White spruceshowed activity at that positionin 79% of its germinants;only 1% of the pure sitka sprucegerminants had similaractivity. Isoenzymevariation between stands of pure Sitka sprucewas less variablethan that betweeninterior white spruce stands (mean distinctionvalues were 0.11 for Sitka and 0.32 for white spruce). Clusteranalysis showedall six pure Sitka sprucepopulations to be similarat .93, whereaspure white sprucepopulations werenot similaruntil .69. Introduction mining quantitatively the genetic composition of Hybrids between Picea glauca (Moench) Voss and stands suspected of being of hybrid origin would be Sitka spruce Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr. were of great use to foresters and researchers. -

Using Multiple Methodologies to Understand Within Species Variability of Adelges and Pineus (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha) Tav Aronowitz University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2017 Using Multiple Methodologies to Understand within Species Variability of Adelges and Pineus (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha) Tav Aronowitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Aronowitz, Tav, "Using Multiple Methodologies to Understand within Species Variability of Adelges and Pineus (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha)" (2017). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 713. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/713 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING MULTIPLE METHODOLOGIES TO UNDERSTAND WITHIN SPECIES VARIABILITY OF ADELGES AND PINEUS (HEMIPTERA: STERNORRHYNCHA) A Thesis Presented by Tav (Hanna) Aronowitz to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Natural Resources May, 2017 Defense Date: March 6, 2016 Thesis Examination Committee: Kimberly Wallin, Ph.D., Advisor Ingi Agnarsson, Ph.D., Chairperson James D. Murdoch, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT The species of two genera in Insecta: Hemiptera: Adelgidae were investigated through the lenses of genetics, morphology, life cycle and host species. The systematics are unclear due to complex life cycles, including multigenerational polymorphism, host switching and cyclical parthenogenesis. I studied the hemlock adelgids, including the nonnative invasive hemlock woolly adelgid on the east coast of the United States, that are currently viewed as a single species. -

Integrating Cultural Tactics Into the Management of Bark Beetle and Reforestation Pests1

DA United States US Department of Proceedings --z:;;-;;; Agriculture Forest Service Integrating Cultural Tactics into Northeastern Forest Experiment Station the Management of Bark Beetle General Technical Report NE-236 and Reforestation Pests Edited by: Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team J.C. Gregoire A.M. Liebhold F.M. Stephen K.R. Day S.M.Salom Vallombrosa, Italy September 1-3, 1996 Most of the papers in this publication were submitted electronically and were edited to achieve a uniform format and type face. Each contributor is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of the contributors from outside the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. Some participants did not submit papers so they have not been included. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Remarks about pesticides appear in some technical papers contained in these proceedings. Publication of these statements does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the conference sponsors, nor does it imply that uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by State and Federal Law. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agencies. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish and other wildlife - if they are not handled and applied properly. -

Bucket Cable Trap Technique for Capturing Black Bears on Prince of Wales Island, Southeast Alaska Boyd Porter

Wildlife Special Publication ADF&G/DWC/WSP–2021–1 Bucket Cable Trap Technique for Capturing Black Bears on Prince of Wales Island, Southeast Alaska Boyd Porter Stephen Bethune ©2012 ADF&G. Photo by Stephen Bethune. 2021 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation Wildlife Special Publication ADF&G/DWC/WSP-2021-1 Bucket Cable Trap Technique for Capturing Black Bears on Prince of Wales Island, Southeast Alaska PREPARED BY: Boyd Porter Wildlife Biologist1 Stephen Bethune Area Wildlife Biologist APPROVED BY: Richard Nelson Management Coordinator REVIEWED BY: Charlotte Westing Cordova Area Wildlife Biologist PUBLISHED BY: Sky M. Guritz Technical Reports Editor ©2021 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation PO Box 115526 Juneau, AK 99811-5526 Hunters are important founders of the modern wildlife conservation movement. They, along with trappers and sport shooters, provided funding for this publication through payment of federal taxes on firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment, and through state hunting license and tag fees. This funding provided support for Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Black Bear Survey and Inventory Project 17.0. 1 Retired Special Publications include reports that do not fit in other categories in the division series, such as techniques manuals, special subject reports to decision making bodies, symposia and workshop proceedings, policy reports, and in-house course materials. This Wildlife Special Publication was reviewed and approved for publication by Richard Nelson, Region I Management Coordinator for the Division of Wildlife Conservation. Wildlife Special Publications are available via the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s public website (www.adfg.alaska.gov) or by contacting Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Wildlife Conservation, PO Box 115526, Juneau, AK 99811-5526; phone: (907) 465- 4190; email: [email protected]. -

Sitka Spruce and Engelmann Spruce in Northwest California and Across

Sitka spruce and www.conifercountry.com Pinaceae Engelmann spruce in Sitka spruce Picea sitchensis perennial cones have scales which are soft to the touch—a stark contrast to northwest California and the prickly needles bark has flakey, circular platelets— across the West sun bleached in a dune forrest Bark: thin with circular platelets that flake off; depending on age, color ranges from pale brown when young to dark brown when older (if you can see under mosses). Needles: 1”, dark green, very sharp at the tip, radiate from stem in all directions, tend to point forward (similar to Engelmann), stomatal bloom on underside of needle. Cones: 1”-3”, yellow when young aging to tan; scales are thin and papery with rounded tips Habitat: coastal, wet, 0’-1000’ www.conifercountry.com Pinaceae Engelmann spruce Picea engelmannii short needles are the sharpest of any conifer in the Klamath Mountains bases of trees are buttressed, offering comfortable seating to revel in the conifer diversity of the Russian Wilderness Bark: purplish to reddish-brown, thin, loosely attached circular scales appearing much darker than those of Brewer spruce Needles: one inch long, pointed at tip, roll in fingers, very sharp, with branches often growing upward Cones: 1”-2”, Range* map for: Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) bearing flexible papery scales with irregular, ragged tips, softer tips than Brewer Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) spruce Habitat: 3500’-6000’, riparian CA Range: drainages around Russian Peak in the Russian Wilderness, often dominating; also, Clark and Hat creeks in Shasta * based on Little (1971),Griffin and Critchfield (1976), and Van Pelt (2001) County www.conifercountry.com Michael Kauffmann | www.conifercountry.com Range* map for: Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) * based on Little (1971),Griffin and Critchfield (1976), and Van Pelt (2001) Michael Kauffmann | www.conifercountry.com. -

Growth and Yield of Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock at Cascade Head Experimental Forest, Oregon

United States Department of i Agriculture Growth and Yield of Sitka Forest Service Pacific Northwest Spruce and Western Forest and Range Experiment Station Research Paper Hemlock at Cascade Head PNW-325 September 1984 Experimental Forest, Oregon Stephen H. Smith, John F. Bell, Francis R. Herman, and Thomas See Authors STEPHEN H. SMITH was a graduate student, College of Forestry Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. He is now with Potlatch Corporation, Lewiston, Idaho. JOHN F. BELL is a professor, Forest Management, College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. FRANCIS R. HERMAN is a mensurationist, retired, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fairbanks, Alaska. THOMAS SEE was a graduate student, College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. He is now with Continental Systems, Inc., Portland, Oregon. Abstract Summary Smith, Stephen H.; Bell, John F.; Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Herman, Francis R.; See, Thomas. Carr.) and western hemlock (Tsuga Growth and yield of Sitka spruce heterophylla (Raf.) Sarg.) are the and western hemlock at Cascade principal components of the Pacific Head Experimental Forest, Oregon. Northwest coastal fog belt type (Meyer Res. Pap. PNW-325. Portland, OR: 1937) or the Picea sitchensis zone U.S. Department of Agriculture, (Franklin and Dyrness 1973) found Forest Service, Pacific Northwest along the Oregon and Washington Forest and Range Experiment Sta- coasts. The tremendous potential for tion; 1984. 30 p. rapid growth and high yield of the Sitka spruce-western hemlock type A study established in 83-year-old, ranks it among the most productive even-aged stands of Sitka spruce coniferous types in the world. -

Projecting the Impact of Climate Change on the Spatial Distribution of Six Subalpine Tree Species in South Korea Using a Multi-Model Ensemble Approach

Article Projecting the Impact of Climate Change on the Spatial Distribution of Six Subalpine Tree Species in South Korea Using a Multi-Model Ensemble Approach Sanghyuk Lee 1 , Huicheul Jung 1 and Jaeyong Choi 2,* 1 Korea Adaptation Center for Climate Change, Korea Environment Institute, Sejong 30147, Korea; [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (H.J.) 2 Department of Environment & Forest Resources, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change is recognized as a major threat to global biodiversity and has already caused extensive regional extinction. In particular danger are the plant habitats in subalpine zones, which are more vulnerable to climate change. Evergreen coniferous trees in South Korean subalpine zones are currently designated as a species that need special care given their conservation value, but the reason for their decline and its seriousness remains unclear. This research estimates the potential land suitability (LS) of the subalpine zones in South Korea for six coniferous species vulnerable to climate change in the current time (1970–2000) and two future periods, the 2050s (2041–2060) and the 2070s (2061–2080). We analyze the ensemble-averaged loss of currently suitable habitats in the future, using nine species distribution models (SDMs). Korean arborvitae (Thuja koraiensis) and Khingan fir (Abies nephrolepis) are two species expected to experience significant habitat losses in 2050 (−59.5% under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5 to −65.9% under RCP 8.5 and −56.3% under RCP 4.5 to −57.7% under RCP 8.5, respectively). High extinction risks are estimated for these species, due to the difficulty of finding other suitable habitats with high LS. -

Evaluating a Standardized Protocol and Scale for Determining Non-Native Insect Impact

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 55: 61–83 (2020) Expert assessment of non-native insect impacts 61 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.55.38981 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions The impact is in the details: evaluating a standardized protocol and scale for determining non-native insect impact Ashley N. Schulz1, Angela M. Mech2, 15, Craig R. Allen3, Matthew P. Ayres4, Kamal J.K. Gandhi5, Jessica Gurevitch6, Nathan P. Havill7, Daniel A. Herms8, Ruth A. Hufbauer9, Andrew M. Liebhold10, 11, Kenneth F. Raffa12, Michael J. Raupp13, Kathryn A. Thomas14, Patrick C. Tobin2, Travis D. Marsico1 1 Arkansas State University, Department of Biological Sciences, PO Box 599, State University, AR 72467, USA 2 University of Washington, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, 123 Anderson Hall, 3715 W Stevens Way NE, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 3 U.S. Geological Survey, Nebraska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Unit, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 423 Hardin Hall, 3310 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, NE 68583, USA 4 Dartmouth College, Department of Biological Sciences, 78 College Street, Hanover, NH 03755, USA 5 The University of Georgia, Daniel B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, 180 E. Green St., Athens, GA 30602, USA 6 Stony Brook University, Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA 7 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 51 Mill Pond Rd., Hamden, CT 06514, USA 8 The Davey Tree Expert Company, 1500 N Mantua St., Kent, OH 44240, USA