Haemocystidium Spp., a Species Complex Infecting Ancient Aquatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Probiotic Administration During

EFFECTS OF PROBIOTIC ADMINISTRATION DURING COCCIDIOSIS VACCINATION ON PERFORMANCE AND LESION DEVELOPMENT IN BROILERS A Thesis by Anthony Emil Klein, Jr. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2009 Major Subject: Poultry Science EFFECTS OF PROBIOTIC ADMINISTRATION DURING COCCIDIOSIS VACCINATION ON PERFORMANCE AND LESION DEVELOPMENT IN BROILERS A Thesis by Anthony Emil Klein, Jr. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, David J. Caldwell Committee Members, James A. Byrd Morgan B. Farnell Jason T. Lee Head of Department, John B. Carey August 2009 Major Subject: Poultry Science iii ABSTRACT Effects of Probiotic Administration during Coccidiosis Vaccination on Performance and Lesion Development in Broilers. (August 2009) Anthony Emil Klein, Jr., B.S., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. David J. Caldwell The principal objective of this investigation was to evaluate coccidiosis vaccination, with or without probiotic administration, for effects on broiler performance and clinical indices of infection due to field strain Eimeria challenge during pen trials of commercially applicable durations. During trials 1 and 2, body weights of vaccinated broilers were reduced (P<0.05) compared to other experimental groups during rearing through the grower phase. Final body weights, however, were not different among experimental groups at the termination of each trial. Similarly, feed conversion in trials 1 and 2 was increased (P<0.05) in vaccinated broilers during rearing through the grower phase when compared to non-vaccinated broilers. -

Haemogregariny Parazitující U Želv Rodu Pelusios: Fylogenetické Vztahy, Morfologie a Hostitelská Specifita

Haemogregariny parazitující u želv rodu Pelusios: fylogenetické vztahy, morfologie a hostitelská specifita Diplomová práce Bc. Aneta Maršíková Školitel: MVDr. Jana Kvičerová, Ph.D. Školitel specialista: doc. MVDr. Pavel Široký, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2016 Maršíková A., 2016: Haemogregariny parazitující u želv rodu Pelusios: fylogenetické vztahy, morfologie a hostitelská specifita. [Haemogregarines in Pelusios turtles: phylogenetic relationships, morphology, and host specificity, MSc. Thesis, in Czech] – 68 pp., Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, České Budějovice, Czech Republic. Annotation: The study deals with phylogenetic relationships, morphology and host specificity of blood parasites Haemogregarina sp. infecting freswater turtles of the genus Pelusios from Africa. Results of phylogenetic analyses are also used for clarification of phylogenetic relationships between "haemogregarines sensu lato" and genus Haemogregarina. Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě – v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných Přírodovědeckou fakultou - elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. -

Journal of Parasitology

Journal of Parasitology Eimeria taggarti n. sp., a Novel Coccidian (Apicomplexa: Eimeriorina) in the Prostate of an Antechinus flavipes --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: 17-111R1 Full Title: Eimeria taggarti n. sp., a Novel Coccidian (Apicomplexa: Eimeriorina) in the Prostate of an Antechinus flavipes Short Title: Eimeria taggarti n. sp. in Prostate of Antechinus flavipes Article Type: Regular Article Corresponding Author: Jemima Amery-Gale, BVSc(Hons), BAnSci, MVSc University of Melbourne Melbourne, Victoria AUSTRALIA Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Melbourne Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Jemima Amery-Gale, BVSc(Hons), BAnSci, MVSc First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Jemima Amery-Gale, BVSc(Hons), BAnSci, MVSc Joanne Maree Devlin, BVSc(Hons), MVPHMgt, PhD Liliana Tatarczuch David Augustine Taggart David J Schultz Jenny A Charles Ian Beveridge Order of Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: A novel coccidian species was discovered in the prostate of an Antechinus flavipes (yellow-footed antechinus) in South Australia, during the period of post-mating male antechinus immunosuppression and mortality. This novel coccidian is unusual because it develops extra-intestinally and sporulates endogenously within the prostate gland of its mammalian host. Histological examination of prostatic tissue revealed dense aggregations of spherical and thin-walled tetrasporocystic, dizoic sporulated coccidian oocysts within tubular lumina, with unsporulated oocysts and gamogonic stages within the cytoplasm of glandular epithelial cells. This coccidian was observed occurring concurrently with dasyurid herpesvirus 1 infection of the antechinus' prostate. Eimeria- specific 18S small subunit ribosomal DNA PCR amplification was used to obtain a partial 18S rDNA nucleotide sequence from the antechinus coccidian. -

Culture of Exoerythrocytic Forms in Vitro

Advances in PARASITOLOGY VOLUME 27 Editorial Board W. H. R. Lumsden University of Dundee Animal Services Unit, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, P.O. Box 120, Dundee DDI 9SY, UK P. Wenk Tropenmedizinisches Institut, Universitat Tubingen, D7400 Tubingen 1, Wilhelmstrasse 3 1, Federal Republic of Germany C. Bryant Department of Zoology, Australian National University, G.P.O. Box 4, Canberra, A.C.T. 2600, Australia E. J. L. Soulsby Department of Clinical Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 OES, UK K. S. Warren Director for Health Sciences, The Rockefeller Foundation, 1133 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10036, USA J. P. Kreier Department of Microbiology, College of Biological Sciences, Ohio State University, 484 West 12th Avenue, Columbus, Ohio 43210-1292, USA M. Yokogawa Department of Parasitology, School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan Advances in PARASITOLOGY Edited by J. R. BAKER Cambridge, England and R. MULLER Commonwealth Institute of Parasitology St. Albans, England VOLUME 27 1988 ACADEMIC PRESS Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers London San Diego New York Boston Sydney Tokyo Toronto ACADEMIC PRESS LIMITED 24/28 Oval Road LONDON NW 1 7DX United States Edition published by ACADEMIC PRESS INC. San Diego, CA 92101 Copyright 0 1988, by ACADEMIC PRESS LIMITED All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by photostat, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publishers British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Advances in parasitology.-Vol. 27 1. Veterinary parasitology 591.2'3 SF810.A3 ISBN Cb12-031727-3 ISSN 0065-308X Typeset by Latimer Trend and Company Ltd, Plymouth, England Printed in Great Britain by Galliard (Printers) Ltd, Great Yarmouth CONTRIBUTORS TO VOLUME 27 B. -

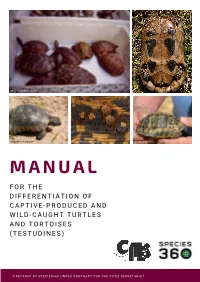

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

(Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) Haemoparasites

Biological Forum – An International Journal 8(1): 331-337(2016) ISSN No. (Print): 0975-1130 ISSN No. (Online): 2249-3239 Molecular identification of Hepatozoon Miller, 1908 (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) haemoparasites in Podarcis muralis lizards from northern Italy and detection of conserved motifs in the 18S rRNA gene Simona Panelli, Marianna Bassi and Enrica Capelli Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Section of Animal Biology, Laboratory of Immunology and Genetic Analyses and Centre for Health Technologies (CHT)/University of Pavia, Via Taramelli 24, 27100 Pavia, Italy (Corresponding author: Enrica Capelli, [email protected]) (Received 22 March, 2016, Accepted 06 April, 2016) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: This study applies a non-invasive molecular test on common wall lizards (Podarcis muralis) collected in Northern Italy in order to i) identify protozoan blood parasites using primers targeting a portion of haemogregarine 18S rRNA; ii) perform a detailed bioinformatic and phylogenetic analysis of amplicons in a context where sequence analyses data are very scarce. Indeed the corresponding phylum (Apicomplexa) remains the poorest-studied animal group in spite of its significance for reptile ecology and evolution. A single genus, i.e., Hepatozoon Miller, 1908 (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) and an identical infecting genotype were identified in all positive hosts. Bioinformatic analyses identified highly conserved sequence patterns, some of which known to be involved in the host-parasite cross-talk. Phylogenetic analyses evidenced a limited host specificity, in accord with existing data. This paper provides the first Hepatozoon sequence from P. muralis and one of the few insights into the molecular parasitology, sequence analysis and phylogenesis of haemogregarine parasites. -

Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Evidence for a Cryptic Plastid in the Colpodellid Voromonas Pontica, a Close Relative of Chromerids and Apicomplexan Parasites

Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Evidence for a Cryptic Plastid in the Colpodellid Voromonas pontica, a Close Relative of Chromerids and Apicomplexan Parasites Gillian H. Gile*, Claudio H. Slamovits Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Abstract Colpodellids are free-living, predatory flagellates, but their close relationship to photosynthetic chromerids and plastid- bearing apicomplexan parasites suggests they were ancestrally photosynthetic. Colpodellids may therefore retain a cryptic plastid, or they may have lost their plastids entirely, like the apicomplexan Cryptosporidium. To find out, we generated transcriptomic data from Voromonas pontica ATCC 50640 and searched for homologs of genes encoding proteins known to function in the apicoplast, the non-photosynthetic plastid of apicomplexans. We found candidate genes from multiple plastid-associated pathways including iron-sulfur cluster assembly, isoprenoid biosynthesis, and tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, along with a plastid-type phosphate transporter gene. Four of these sequences include the 59 end of the coding region and are predicted to encode a signal peptide and a transit peptide-like region. This is highly suggestive of targeting to a cryptic plastid. We also performed a taxon-rich phylogenetic analysis of small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences from colpodellids and their relatives, which suggests that photosynthesis was lost more than once in colpodellids, and independently in V. pontica and apicomplexans. Colpodellids therefore represent a valuable source of comparative data for understanding the process of plastid reduction in humanity’s most deadly parasite. Citation: Gile GH, Slamovits CH (2014) Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Evidence for a Cryptic Plastid in the Colpodellid Voromonas pontica, a Close Relative of Chromerids and Apicomplexan Parasites. -

A New Species of Hepatozoon (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) from Python Regius (Serpentes: Pythonidae) and Its Experimental Transmission by a Mosquito Vector

J. Parasitol., 93(?), 2007, pp. 1189–1198 ᭧ American Society of Parasitologists 2007 A NEW SPECIES OF HEPATOZOON (APICOMPLEXA: ADELEORINA) FROM PYTHON REGIUS (SERPENTES: PYTHONIDAE) AND ITS EXPERIMENTAL TRANSMISSION BY A MOSQUITO VECTOR Michal Sloboda, Martin Kamler, Jana Bulantova´*, Jan Voty´pka*†, and David Modry´† Department of Parasitology, University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Palacke´ho 1-3, 612 42 Brno, Czech Republic. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Hepatozoon ayorgbor n. sp. is described from specimens of Python regius imported from Ghana. Gametocytes were found in the peripheral blood of 43 of 55 snakes examined. Localization of gametocytes was mainly inside the erythrocytes; free gametocytes were found in 15 (34.9%) positive specimens. Infections of laboratory-reared Culex quinquefasciatus feeding on infected snakes, as well as experimental infection of juvenile Python regius by ingestion of infected mosquitoes, were performed to complete the life cycle. Similarly, transmission to different snake species (Boa constrictor and Lamprophis fuliginosus) and lizards (Lepidodactylus lugubris) was performed to assess the host specificity. Isolates were compared with Hepatozoon species from sub-Saharan reptiles and described as a new species based on the morphology, phylogenetic analysis, and a complete life cycle. Hemogregarines are the most common intracellular hemo- 3 genera (Telford et al., 2004). Low host specificity of Hepa- parasites found in reptiles. The Hemogregarinidae, Karyolysi- tozoon spp. is supported by experimental transmissions between dae, and Hepatozoidae are distinguished based on the different snakes from different families. Ball (1967) observed experi- developmental patterns in definitive (invertebrate) hosts oper- mental parasitemia with Hepatozoon rarefaciens in the Boa ating as vectors; all 3 families have heteroxenous life cycles constrictor (Boidae); the vector was Culex tarsalis, which had (Telford, 1984). -

Clerissi-2018-Frontiersmicrobi

Protists Within Corals: The Hidden Diversity Camille Clerissi, Sébastien Brunet, Jeremie Vidal-Dupiol, Mehdi Adjeroud, Pierre Lepage, Laure Guillou, Jean-Michel Escoubas, Eve Toulza To cite this version: Camille Clerissi, Sébastien Brunet, Jeremie Vidal-Dupiol, Mehdi Adjeroud, Pierre Lepage, et al.. Protists Within Corals: The Hidden Diversity. Frontiers in Microbiology, Frontiers Media, 2018, 9, pp.2043. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02043. hal-01887637 HAL Id: hal-01887637 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01887637 Submitted on 7 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. fmicb-09-02043 August 30, 2018 Time: 10:39 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 31 August 2018 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02043 Protists Within Corals: The Hidden Diversity Camille Clerissi1*, Sébastien Brunet2, Jeremie Vidal-Dupiol3, Mehdi Adjeroud4, Pierre Lepage2, Laure Guillou5, Jean-Michel Escoubas6 and Eve Toulza1* 1 Univ. Perpignan Via Domitia, IHPE UMR 5244, CNRS, IFREMER, Univ. Montpellier, Perpignan, France, 2 McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3 IFREMER, IHPE UMR 5244, Univ. Perpignan Via Domitia, CNRS, Univ. Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 4 Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, UMR 9220 ENTROPIE & Laboratoire d’Excellence CORAIL, Université de Perpignan, Perpignan, France, 5 CNRS, UMR 7144, Sorbonne Universités, Université Pierre et Marie Curie – Paris 6, Station Biologique de Roscoff, Roscoff, France, 6 CNRS, IHPE UMR 5244, Univ. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Why the –Omic Future of Apicomplexa Should Include Gregarines Julie Boisard, Isabelle Florent

Why the –omic future of Apicomplexa should include Gregarines Julie Boisard, Isabelle Florent To cite this version: Julie Boisard, Isabelle Florent. Why the –omic future of Apicomplexa should include Gregarines. Biology of the Cell, Wiley, 2020, 10.1111/boc.202000006. hal-02553206 HAL Id: hal-02553206 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02553206 Submitted on 24 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Article title: Why the –omic future of Apicomplexa should include Gregarines. Names of authors: Julie BOISARD1,2 and Isabelle FLORENT1 Authors affiliations: 1. Molécules de Communication et Adaptation des Microorganismes (MCAM, UMR 7245), Département Adaptations du Vivant (AVIV), Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CNRS, CP52, 57 rue Cuvier 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. 2. Structure et instabilité des génomes (STRING UMR 7196 CNRS / INSERM U1154), Département Adaptations du vivant (AVIV), Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. Short Title: Gregarines –omics for Apicomplexa studies -

Redalyc.Protozoan Infections in Farmed Fish from Brazil: Diagnosis

Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária ISSN: 0103-846X [email protected] Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Brasil Laterça Martins, Mauricio; Cardoso, Lucas; Marchiori, Natalia; Benites de Pádua, Santiago Protozoan infections in farmed fish from Brazil: diagnosis and pathogenesis. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária, vol. 24, núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2015, pp. 1- 20 Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Jaboticabal, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=397841495001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Review Article Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol., Jaboticabal, v. 24, n. 1, p. 1-20, jan.-mar. 2015 ISSN 0103-846X (Print) / ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015013 Protozoan infections in farmed fish from Brazil: diagnosis and pathogenesis Infecções por protozoários em peixes cultivados no Brasil: diagnóstico e patogênese Mauricio Laterça Martins1*; Lucas Cardoso1; Natalia Marchiori2; Santiago Benites de Pádua3 1Laboratório de Sanidade de Organismos Aquáticos – AQUOS, Departamento de Aquicultura, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC, Florianópolis, SC, Brasil 2Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária e Extensão Rural de Santa Catarina – Epagri, Campo Experimental de Piscicultura de Camboriú, Camboriú, SC, Brasil 3Aquivet Saúde Aquática, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brasil Received January 19, 2015 Accepted February 2, 2015 Abstract The Phylum Protozoa brings together several organisms evolutionarily different that may act as ecto or endoparasites of fishes over the world being responsible for diseases, which, in turn, may lead to economical and social impacts in different countries.