Why Is Op. 6 Still So Difficult to Understand?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 Program Notes

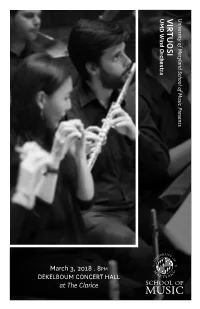

UMD Wind OrchestraUMD VIRTUOSI University Maryland of School Music of Presents March 3, 2018 . 8PM DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL at The Clarice University of Maryland School of Music presents VIRTUOSI University of Maryland Wind Orchestra PROGRAM Michael Votta Jr., music director James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano Kammerkonzert .........................................................................................................................Alban Berg I. Thema scherzoso con variazioni II. Adagio III. Rondo ritmico con introduzione James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano INTERMISSION Serenade for Brass, Harp,Piano, ........................................................Willem van Otterloo Celesta, and Percussion I. Marsch II. Nocturne III. Scherzo IV. Hymne Danse Funambulesque .....................................................................................................Jules Strens I wander the world in a ..................................................................... Christopher Theofanidis dream of my own making 2 MICHAEL VOTTA, JR. has been hailed by critics as “a conductor with ABOUT THE ARTISTS the drive and ability to fully relay artistic thoughts” and praised for his “interpretations of definition, precision and most importantly, unmitigated joy.” Ensembles under his direction have received critical acclaim in the United States, Europe and Asia for their “exceptional spirit, verve and precision,” their “sterling examples of innovative programming” and “the kind of artistry that is often thought to be the exclusive -

Isang Yun World Premiere: 06 Nov 1983 Trossingen, Germany Hugo Noth, Accordion; Joachim-Quartett

9790202514955 Accordion, String Quartet Isang Yun World Premiere: 06 Nov 1983 Trossingen, Germany Hugo Noth, accordion; Joachim-Quartett Contemplation 1988 11 min for two violas 9790202516089 2 Violas Isang Yun photo © Booseyprints World Premiere: 09 Oct 1988 Philharmonie, Kammermusiksaal, Berlin, Germany Eckart Schloifer & Brett Dean ENSEMBLE AND CHAMBER WITHOUT VOICE(S) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Bläseroktett Distanzen 1993 18 min 1988 16 min for wind octet with double bass ad lib. for wind quintet and string quintet 2ob.2cl.2bn-2hn-db(ad lib) 9790202516409 (Full score) 9790202518427 (Full score) World Premiere: 09 Oct 1988 World Premiere: 19 Feb 1995 Philharmonie, Kammermusiksaal, Berlin, Germany Stuttgart, Germany Scharoun Ensemble Stuttgarter Bläserakademie Conductor: Heinz Holliger Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Bläserquintett Duo for cello and harp 1991 16 min 1984 13 min for wind quintet (or cello and piano) fl.ob.cl.bn-hn 9790202514986 Cello, Harp 9790202580790 Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, Horn (score & parts) 9790202580806 Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon (Full Score) World Premiere: 27 May 1984 Ingelheim, Germany Ulrich Heinen, cello / Gerda Ockers, harp World Premiere: 06 Aug 1991 Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, Altenhof bei Kiel, Germany Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Albert Schweitzer Quintett Espace II Concertino 1993 13 min 1983 17 min for cello, harp and oboe (ad lib.) for accordion and string quartet 9790202517475 Cello, Harp, (optional Oboe) 9790202518700 Accordion, String Quartet (string parts) World Premiere: 17 Sep 1993 St. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

November 6, 2018 to the Board of Directors of the Voice Foundation

November 6, 2018 To the Board of Directors of The Voice Foundation, This is a letter of interest in the Van L. Lawrence Fellowship, to be awarded in 2019. As I look through the bullet points to be included in this document, it’s clear to me that what I should really be submitting is simply a thank-you note, since attending the Annual Symposium has comprehensively re-shaped me as a vocal pedagogue since I began attending four years ago. The singers I teach (at the University of Missouri, and as of this year, at the Jacobs School of Music at IU-Bloomington) are music majors ranging from freshmen to young professionals, c. 18-26 years old. The freshmen arrive having had some introductory experience with vocal instruction, but are basically wide-open to the unknown. They leave after their first lesson knowing what vowel formants are and where they are located, understanding the contribution of harmonics to an expressive vocal color, and demonstrating a solid rudimentary understanding of resonance strategies (including divergence and off-resonance, aka inertance). I’ve been diligent in streamlining this information; I want them to gain fluency in these concepts before they even think twice. The rapidity with which these talented students assimilate a paradigm so squarely founded on acoustics and physiology is inspiring, and very exciting. As recently as three years ago, I felt obliged to defend the validity of these ideas, and my qualifications to present them as established fact. Now, that defensive stance (at least with these superlative students) is already obsolete. -

Camera Lucida Symphony, Among Others

Pianist REIKO UCHIDA enjoys an active career as a soloist and chamber musician. She performs Taiwanese-American violist CHE-YEN CHEN is the newly appointed Professor of Viola at regularly throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe, in venues including Suntory Hall, the University of California, Los Angeles Herb Alpert School of Music. He is a founding Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, the 92nd Street Y, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, member of the Formosa Quartet, recipient of the First-Prize and Amadeus Prize winner the Kennedy Center, and the White House. First prize winner of the Joanna Hodges Piano of the 10th London International String Quartet Competition. Since winning First-Prize Competition and Zinetti International Competition, she has appeared as a soloist with the in the 2003 Primrose Competition and “President Prize” in the Lionel Tertis Competition, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Santa Fe Symphony, Greenwich Symphony, and the Princeton Chen has been described by San Diego Union Tribune as an artist whose “most impressive camera lucida Symphony, among others. She made her New York solo debut in 2001 at Weill Hall under the aspect of his playing was his ability to find not just the subtle emotion, but the humanity Sam B. Ersan, Founding Sponsor auspices of the Abby Whiteside Foundation. As a chamber musician she has performed at the hidden in the music.” Having served as the principal violist of the San Diego Symphony for Chamber Music Concerts at UC San Diego Marlboro, Santa Fe, Tanglewood, and Spoleto Music Festivals; as guest artist with Camera eight seasons, he is the principal violist of the Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra, and has Lucida, American Chamber Players, and the Borromeo, Talich, Daedalus, St. -

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in the Department of French, the School of Music, and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought Mitch Renaud, 2015 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay, Department of French and CSPT Supervisor Christopher Butterfield, School of Music Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross, Department of English and CSPT Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay (Department of French and CSPT) Supervisor Christopher Butterfield (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross (Department of English and CSPT) Outside Member Noise is noisy. Its multiple definitions cover one another in such a way as to generate what they seek to describe. My thesis tracks the ways in which noise can be understood historically and theoretically. I begin with the Skandalkonzert that took place in Vienna in 1913. I then extend this historical example into a theoretical reading of the noise of Derrida’s Of Grammatology, arguing that sound and noise are the unheard of his text, and that Derrida’s thought allows us to hear sound studies differently. Writing on sound must listen to the noise of the motion of différance, acknowledge the failings, fading, and flailings of sonic discourse, and so keep in play the aporias that constitute the field of sound itself. -

The Modernist Kaleidoscope: Schoenberg's Reception History in England, America, Germany and Austria 1908-1924 by Sarah Elain

The Modernist Kaleidoscope: Schoenberg’s Reception History in England, America, Germany and Austria 1908-1924 by Sarah Elaine Neill Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ R. Larry Todd, Supervisor ___________________________ Severine Neff ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 ABSTRACT The Modernist Kaleidoscope: Schoenberg’s Reception History in England, America, Germany and Austria 1908-1924 by Sarah Elaine Neill Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ R. Larry Todd, Supervisor ___________________________ Severine Neff ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Sarah Elaine Neill 2014 Abstract Much of our understanding of Schoenberg and his music today is colored by early responses to his so-called free-atonal work from the first part of the twentieth century, especially in his birthplace, Vienna. This early, crucial reception history has been incredibly significant and subversive; the details of the personal and political motivations behind deeply negative or manically positive responses to Schoenberg’s music have not been preserved with the same fidelity as the scandalous reactions themselves. We know that Schoenberg was feared, despised, lauded, and imitated early in his career, but much of the explanation as to why has been forgotten or overlooked. -

CHAN 9999 BOOK.Qxd 10/5/07 3:38 Pm Page 2

CHAN 9999 front.qxd 10/5/07 3:31 pm Page 1 CHANDOS CHAN 9999 CHAN 9999 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 3:38 pm Page 2 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Complete Chamber Music String Quartet, Op. 3 (1909–10) 25:53 1 I Langsam 10:18 2 II Mäßige Viertel 10:59 premiere recording 3 Hier ist Friede, Op. 4 No. 5 (1912)* 4:34 from Altenberg Lieder arranged for piano, harmonium, violin and cello by Alban Berg (1917) Ziemlich langsam premiere recording Four Pieces, Op. 5 (1913) 8:02 for clarinet and piano arranged for viola and piano by Henk Guittart (1992) 4 I Mäßig 1:28 5 II Sehr langsam 2:08 6 III Sehr rasch 1:19 7 IV Langsam 3:05 8 Adagio* 13:13 Alban Berg, c. 1925 Second movement from the Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 wind instruments (1923–25) arranged for violin, clarinet and piano by Alban Berg (1935) 3 CHAN 9999 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 3:38 pm Page 4 Berg: Complete Chamber Music Lyric Suite (1925–26) 28:41 With the exception of the Lyric Suite and the writing songs for performance by and within for string quartet Chamber Concerto, all the works on the the family. Writing to the publisher Emil 9 Allegretto giovale 3:08 present CD were written in the three years Hertzka in 1910, Schoenberg observed: from 1910 to 1913, when Alban Berg [Alban Berg] is an extraordinarily gifted composer, 10 Andante amoroso 6:15 (1885–1935) was in his mid-twenties. but the state he was in when he came to me was 11 Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico 3:24 The earliest work, the String Quartet, Op. -

Kenneth Woods- Repertoire

Kenneth Woods- Conductor Orchestral Repertoire Operatic repertoire follows below Adam, Adolpe: Giselle (complete ballet staged) Adams, John Violin Concerto Arnold, Malcolm: Serenade for Guitar and Strings Concerto for Guitar Scottish Dances Applebaum, Edward: Symphony No. 4 Bach, J.S.: St. John Passion St. Matthew Passion Christmas Oratorio Magnificat Cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme BWV 140 Brandenberg Concerti, No.’s 1, 3, 4 and 5 Violin Concerti in A minor and E major Concerto for Two Violins Concerto for Violin and Oboe Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B minor Bacewicz, Grażyna Concerto for String Orchestra Barber, Samuel: Prayer of Kirkegarde Overture to “The School for Scandal” Adagio for Strings Violin Concerto Cello Concerto First Essay Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance Bartók, Bela: Divertimento for Strings Concerto for Orchestra Two Portraits Violin Concerto No. 2 Piano Concerti No.’s 2 and 3 Viola Concerto Miraculous Mandarin (Complete and Suite) Beethoven, Ludwig van: Symphonies No.’s 1-9 Mass in C Major Overtures: Coriolan, Leonore 1, 2 and 3, Fidelio, Egmont, Creatures of Prometheus, King Stephen Incidental Music to “Egmont” Piano Concerti No.’s 1-5 Kenneth Woods- conductor www.kennethwoods.net Violin Concerto Triple Concerto String Quartet in F minor op. 95, “Serioso,” arr. Gustav Mahler Leonore Overture No. 3 arr. Gustav Mahler Berg, Alban: Three Orchestra Pieces Kammerkonzert Violin Concerto Berio, Luciano: Folk Songs Serenata I for Flute and 14 Intruments Berlioz, Hector: Harold in Italy Symphonie Fantastique Damnation of Faust Overtures: Benvenuto Cellini, Roman Carnival, Corsaire, Beatrice and Benedict Te Deum Bernstein, Leonard: Overture to Candide Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Symphony No. -

Die Altenberg-Lieder Sind Vorläufer Der Großen Opernfresken Bergs

Drei Orchesterstücke Op.6 Altenberg Lieder Op.4 - Sieben frühe Lieder CHRISTIANE IVEN soprano HY BRID MU LTICHANNEL A L B A N B E R G Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg MARC ALBRECHT Alban Berg (1885 – 1935) Drei Orchesterstücke, Op. 6 (Three pieces for orchestra) 1 Präludium 4. 51 2 Reigen 5. 38 3 Marsch 10. 02 Altenberg Lieder, Op. 4 (Fünf Orchesterlieder nach Ansichtskartentexten von Peter Altenberg) (Five Orchestral Songs to Picture-Postcard Texts by Peter Altenberg) 4 Seele, wie bist du schöner 2. 42 5 Sahst du nach dem Gewitterregen den Wald 1. 24 6 Über die Grenzen des All 1. 33 7 Nichts ist gekommen 1. 29 8 Hier ist Friede 4. 07 Sieben frühe Lieder (Seven early songs) 9 Nacht (Carl Hauptmann) 3. 54 10 Schilflied (Nikolaus Lenau) 2. 11 11 Die Nachtigall (Theodor Storm) 2. 16 12 Traumgekrönt (Rainer Maria Rilke) 2. 52 13 Im Zimmer (Johannes Schlaf) 1. 14 14 Liebesode (Otto Erich Hartleben) 1. 52 15 Sommertage (Paul Hohenberg) 1. 49 Johann Strauss (1825 – 1899) 16 Wein, Weib und Gesang 11. 43 Christiane Iven, soprano Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg conducted by Marc Albrecht Recording venue: Palais de la Musique et de Congrès, Strasbourg, France (Frühe Lieder, 1/2007; Orchesterstücke, Altenberglieder, Wein, Weib und Gesang, 1/2008) Recording producer: Wolfram Nehls Balance engineer: Philipp Knop Editing: Wolfram Nehls Surround Mix: Philipp Knop & Wolfram Nehls Total playing time: 59.46 Biographien auf Deutsch und Französisch finden Sie auf unserer Webseite. Pour les versions allemande et française des biographies, veuillez consulter notre site. www.pentatonemusic.com Alban Berg The Three Orchestral Pieces were writ- Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. -

Library Orders - Music Composition/Electronic Music

LIBRARY ORDERS - MUSIC COMPOSITION/ELECTRONIC MUSIC COMPOSER PRIORITY TITLE FORMAT PUBLISHER PRICE In Collection? Babbitt, Milton A Three Compositions for Piano score Boelke-Bomart 9.50 Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 1, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 2, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 3, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 4, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 5, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 6, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Music for strings, percussion, and celesta score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Berbarian, Cathy A Stripsody : for solo voice score C.F. Peters Corp. 18.70 Berg, Alban A Violin Concerto score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 0.00 YES Berio, Luciano A Sequenza V, for trombone score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 19.95 Berio, Luciano A Sequenza VII; per oboe solo score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 15.95 Berio, Luciano A Sequenza XII : per bassoon solo score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 35.00 Berio, Luciano A Sinfonia, for eight voices and orchestra score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 125.00 Boulez, Pierre A Marteau sans maître : pour voix d'alto et 6 instruments score Warner Brothers Music Pub. -

Clytemnestra

CLYTEMNESTRA Rhian Samuel CLYTEMNESTRA Mahler RÜCKERT-LIEDER Berg ALTENBERG LIEDER RUBY HUGHES BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES / JAC VAN STEEN MAHLER, Gustav (1860—1911) Rückert-Lieder 18'57 1 Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder! 1'25 2 Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft! 2'33 3 Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen 6'20 4 Um Mitternacht 5'50 5 Liebst du um Schönheit (orch. by Max Puttmann) 2'17 BERG, Alban (1885—1935) Altenberg Lieder, Op. 4 10'37 Fünf Orchesterlieder, nach Ansichtkarten-Texten von Peter Altenberg 6 I. Seele, wie bist du schöner 2'54 7 II. Sahst du nach dem Gewitterregen den Wald? 1'07 8 III. Über die Grenzen des All 1'30 9 IV. Nichts ist gekommen 1'21 10 V. Hier ist Friede (Passacaglia) 3'24 2 SAMUEL, Rhian (b. 1944) Clytemnestra for soprano and orchestra (1994) (Stainer & Bell) 24'10 (after Aeschylus — English version assembled by the composer) 11 I. The Chain of Flame 4'41 12 II. Lament for his Absence 4'30 13 III. Agamemnon’s Return — attacca — 4'03 14 IV. The Deed (orchestral) 1'28 15 V. Confession 2'30 16 VI. Defiance 2'33 17 VII. Epilogue: Dirge 4'07 World Première Recording · Recorded in the presence of the composer TT: 54'46 Ruby Hughes soprano BBC National Orchestra of Wales Lesley Hatfield leader Jac van Steen conductor 3 Gustav Mahler: Rückert-Lieder Friedrich Rückert, the celebrated German Romantic poet and scholar, was Gustav Mahler’s poet of choice: for the composer, Rückert’s work represented ‘lyric poetry from the source, all else is lyric poetry of a derivative kind’.