The COMPLETE REPORT Can Be Downloaded Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transatlantic Cooperation and the Prospects for Dialogue

Transatlantic Cooperation and the Prospects for Dialogue The Council for Inclusive Governance (CIG) organized on February 26, 2021 a discussion on trans-Atlantic cooperation and the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue for a group of politicians and civil society representatives from Kosovo and Serbia. Two CIG board members, former senior officials in the U.S. Department of State and the European Commission, took part as well. The meeting specifically addressed the effects of expected revitalized transatlantic cooperation now with President Joe Biden in office, the changes in Kosovo after Albin Kurti’s February 14 election victory, and the prospects of the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue in 2021. The following are a number of conclusions and recommendations based either on consensus or broad agreement. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIG and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), which supports CIG’s initiative on normalization between Kosovo and Serbia. The discussion was held under the Chatham House Rule. Conclusions and recommendations The change of governments in Kosovo and in the US are positive elements for the continuation of the dialogue. However, there are other pressing issues and reluctance both in Belgrade and in Pristina that make it almost impossible for the dialogue to achieve breakthrough this year. • The February 14 election outcome in Kosovo signaled a significant change both at the socio- political level and on the future of the dialogue with Serbia. For the first time since the negotiations with Serbia began in 2011, Kosovo will be represented by a leader who is openly saying that he will not yield to any international pressure to make “damaging agreements or compromises.” “However, this is not a principled position, but rather aimed at gaining personal political benefit,” a speaker, skeptical of Kurti’s stated objectives, said. -

Advancing Normalization Between Kosovo and Serbia

ADVANCING NORMALIZATION BETWEEN KOSOVO AND SERBIA ADVANCING NORMALIZATION BETWEEN KOSOVO AND SERBIA Council for Inclusive Governance New York, 2017 Contents 4 Preface and Acknowledgments 7 Comprehensive Normalization 11 Parliamentary Cooperation 22 Serb Integration and Serb Albanian Relations 32 Challenges of Establishing the Association/Community 39 Serbia’s Internal Dialogue on Kosovo © Council for Inclusive Governance 2017 3 PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Almost twenty years after the war in Kosovo, resolution of the Kosovo-Serbia conflict remains a piece of unfinished business in the Balkans. The process is entering a critical stage. An agreement on comprehensive normalization or a peace treaty under which both sides will commit to mutual respect, peaceful co- existence and hopefully cooperation is within reach. Comprehensive normalization with Kosovo is an obligation for Serbia’s accession to the European Union and is also needed by Pristina in order to move forward. It is unclear, however, what is the most efficient way of getting there. It is not clear how to produce a document that will be acceptable to both sides and a document in the spirit of win-win rather than of win-lose. Since 2010, Serbia and Kosovo have been on a quest to normalize their relations. In Brussels, in 2013, their prime ministers reached the first agreement of principles governing normalization of relations. Implementation deadlines were agreed upon as well. However, five years later the agreement remains to be implemented in full, most notably the provisions on establishing the Association/Community of Serb-Majority Municipalities and on energy. Kosovo’s institutions are not fully functioning in Kosovo’s predominantly ethnically Serb north and Serbia’s parallel administrative institutions continue their existence across Kosovo. -

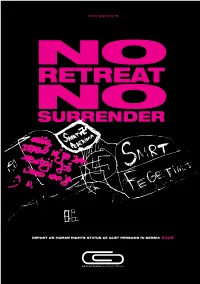

REPORT on HUMAN RIGHTS STATUS of LGBT PERSONS in SERBIA 2011 REPORT PRODUCED BY: Gay Straight Alliance, May 2012

REPORT ON HUMAN RIGHTS STATUS OF LGBT PERSONS IN SERBIA 2011 REPORT PRODUCED BY: Gay Straight Alliance, May 2012 COVER ILLUSTRATION: Collage: Dragan Lončar (Clips from the daily media and parts of attack victims’ statements) TRANSLATION: Vesna Gajišin 02 03 C O N T E N T S I INSTEAD OF AN INTRODUCTION 07 II DOES INSTITUTIONAL DISCRIMINATION 08 OF THE LGBT POPULATION EXIST IN SERBIA? III LEGAL FRAMEWORK 10 IV EVENTS OF IMPORTANCE FOR THE 12 STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE STATUS OF LGBT PEOPLE IN SERBIA IN 2011 V SUMMARY OF THE REPORT 14 VI THE RIGHT TO LIFE 18 VII INVIOLABILITY OF PHYSICAL 19 AND MENTAL INTEGRITY VIII THE RIGHT TO A FAIR TRIAL AND THE 31 RIGHT TO EQUAL PROTECTION OF RIGHTS AND TO A LEGAL REMEDY IX FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY AND 44 FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION X THE RIGHT TO WORK 58 XI HEALTH CARE 60 XII SOCIAL WELFARE 62 XIII THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION 65 COURT DOCUMENTS 69 02 03 T H A N K S ! Members of Gay Straight Alliance Lawyers of Gay Straight Alliance, Aleksandar Olenik and Veroljub Đukić Victims of violence and discrimination who had the courage to speak out and report their cases Partners from the NGO sector: Belgrade Centre for Human Rights, Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence, E8 Centre, Centre for Modern Skills, Centre for Euro-Atlantic Studies, Centre for Cultural Decontamination, Centre for New Politics, Centre for Youth Work, Centre for Empowerment of Young People Living with HIV / AIDS “AS”, Centre for Gender Alternatives – AlteR, Dokukino, European Movement in Serbia, Centre for Free Elections and Democracy - CeSID, Policy Center, Fractal, Civic Initiatives, Centre “Living Upright”, Dr. -

Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians

Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians Ms. Aleksandra Jerkov, President Ms. Delsa Solórzano, Vice‐President (Serbia) (Venezuela) Mr. Ali A. Alaradi, President Ms. Fawzia Koofi Mr. Federico Pinedo Ms. Laurence Dumont (Bahrain) (Afghanistan) (Argentina) (France) Mr. Nassirou Bako‐Arifari Mr. Andrea Caroni Ms. Julie Mukoda Zabwe Mr. David Carter (Benin) (Switzerland) (Uganda) (New Zealand) The Inter-Parliamentary Union, the Headquarters in Geneva (usually in parliamentarian, reinstatement of a world organization of national January) and twice in conjunction previously relinquished parliaments, set up a procedure in with the bi-annual IPU Assemblies parliamentary seat, the effective 1976 for the treatment of (usually March/April and investigation of abuses and legal complaints regarding human rights September/October). On those action against their perpetrators. violations of parliamentarians. It occasions, it examines and adopts entrusted the Committee on the decisions on the cases that have The Committee does everything it Human Rights of Parliamentarians been referred to it. can to nurture a dialogue with the with implementing that procedure. authorities of the countries concerned in its pursuit of a The procedure satisfactory settlement. It is in this Composition The Committee seeks to establish spirit that, during the IPU The Committee is composed of the facts of a given case by Assemblies, the Committee 10 members of parliament, cross-checking and verifying, with regularly meets with the representing the major regions of the authorities of the countries parliamentary delegations of such the world. They are elected in their concerned, the complainants and countries and may suggest sending personal capacity for a mandate of other sources of information, the an on-site mission to help move a five years. -

Human Rights in Serbia 2019

HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA 2019 Belgrade Centre for Human Rights The Belgrade Centre for Human Rights was established by a group of human rights experts and activists in February 1995 as a non-profit, non- governmental organisation. The main purpose of the Centre is to study human rights, to disseminate knowledge about them and to educate individuals engaged in this area. It hopes, thereby, to promote the development of democracy and rule of law in Serbia. Since 1998 Belgrade Centre for Human Right has been publishing Annual Human Rights Report. This Report on Human Rights in Serbia analyses the Constitution and laws of the Republic of Serbia with respect to the civil and poli- tical rights guaranteed by international treaties binding on Serbia, in particular the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the European Convention on Human Rights and Funda- mental Freedoms (ECHR) and its Proto- cols and standards established by the jurisprudence of the UN Human Rights Committee and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Where relevant, the Report also re- views Serbia’s legislation with respect to standards established by specific inter- national treaties dealing with specific human rights, such as the UN Convention against Torture, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the UN Convention on the Elimina- tion of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. For its achievements in the area of human rights, the Centre was awarded the Bruno Kreisky Prize for 2000. -

WITHOUT PUNISHMENT: Maja Forgiven 300 Million Euros The

WITHOUT PUNISHMENT: Maja forgiven 300 million Euros The Prosecution dismissed as obsolete the criminal charges for abuse of official position. The issue considered here is the criminal charge against the current member of the Serbian Progressive Party Presidency filed by Ilija Dević, the unsuccessful investor in building of the bus station in Novi Sad. In 2006 he concluded the contract with then Mayor Maja Gojković on the intercity bus station; he did his part of the job. but the City authorities did not redirect the traffic to the new location. The trials have been being in progress since 2007. In the dismissed criminal charges Dević charged Gojković and her co-workers for the damage inflicted to the City budget in the amount of 400 million dinars. That is the exact amount stated in the final judgement brought in 2014, according to which the City of Novi Sad paid the money to his ATP Vojvodina as the compensation for outstanding liabilitiee. The Prosecutor Works as Instructed by Politicians. The investor of Auto- transport company Vojvodina, Ilija Dević, has accused the Prosecution in Novi Sad for thwarting the proceedings against Maja Gojković and her co- workers because they are high officials of SPP (Serbian Progressive Party). In the press release he has said that the prosecution in Serbia is „open wound of this society“ because they still work „under Eventually, the City had to pay but Gojković and her Progressives will pass without punishment. pressure of tycoons, powerful people, Namely, the Basic Public Prosecutor has decided that criminal groups and all „based on the Law on Criminal Procedure, there are circumstances which permanently exclude their that with the intention prosecution meaning that there is obsolescence of to be liked by the prosecution“. -

Parncipantes Alendus Alliance Progressiste: « Construire Notre

Par$cipantes aendus Alliance progressiste: « Construire notre avenir » 12-13 Mars 2017, Berlin, Germany Argen$na Antonio Bonfa> Socialist Party (PS) Sebas@an Melchor Argen$na Jaime Linares Gen Party (Gen) Ricardo Vazquez Australia Trudy JacKson Australian Labour Party (ALP) Austria Ilia Dib Social Democra@c Party of Chris@an Kern Austria (SPÖ) Georg Niedermühlbichler Andreas Schieder Sebas@an Schublach Bahrain Saeed Mirza Na@onal Democra@c Ac@on Society (Waad) Belarus Ihar Barysau Belarussian Social Democra@c Party (HRAMADA) Belgium Ariane Fontenelle Socialist Party (PS) Elio di Rupo Belgium Jan de BocK Socialist Party (S.PA) Jan Cornillie Bosnia Herzegovina Irfan Cengic Socialist Democra@c Party Sasa Magazinovic (SDP) Davor Vulec Brazil Monica Valente WorKer’s Party (PT) Bulgaria Kris@an Vigenin Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) Krum ZarKov Burkina Faso Moussa Boly Movement of People for Progress (MPP) Cameroon Josh Osih Social Democra@c Front (SDF) Canada Rebecca BlaiKie New Democra@c Party (NDP) Central African RepuBlic Mar@n Ziguele Movement for the Libera@on of the Central African People (MLPC) Chile Pablo Velozo Socialist Party of Chile (PS) Chile German Pino Party for Democracy (PPD) Costa Rica Margarita Bolanos Arquin Ci@zens’Ac@on Party (PAC) Czech RepuBlic Kris@an Malina Czech Social Democra@c Party Bohuslav Sobotka (CSSD) Vladimír Špidla 2 Denmark Jan Juul Christensen Social Democra@c Party Dominican RepuBlic Luis Rodolfo Adinader Corona Modern Revolu@onary Party Rafael Báez Perèz (PRM) Orlando Jorge Mera Orlando Antonio Mar@nez -

GSA-Report-2009.Pdf

www.gsa.org.rs REPORT ON HUMAN RIGHTS STATUS OF GLBT PERSONS IN SERBIA 2009 CONTENTS PREFACE BY BORIS DITTRICH 09 OPENING WORD BY ULRIKE LUNACEK 11 I SUMMARY 13 II INTRODUCTION 15 III RIGHT TO LIFE 17 IV RIGHT TO PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL INTEGRITY 21 V RIGHT TO FAIR TRIAL AND EQUAL PROTECTION 33 UNDER THE LAW VI FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY 39 VII HEALTH PROTECTION 57 VIII RIGHT TO EDUCATION 63 IX ATTITUDE OF THE STATE TOWARDS GLBT POPULATION 67 AUTHORS Boris Milićević, Nenad Sarić, Lazar Pavlović, Mirjana Bogdanović, Veroljub Đukić, Nemanja Ćirilović X THE ATTITUDE OF POLITICAL PARTIES TOWARDS 77 GLBT POPULATION TRANSLATION Ljiljana Madžarević, Vesna Gajišin, Vladimir Lazić XI THE ATTITUDE OF NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL 93 DIZAJN & LAYOUT ORGANIZATIONS TOWARDS GLBT POPULATION Dragan Lončar OTHER CONTRIBUTORS XII MEDIA VIEW ON GLBT POPULATION IN SERBIA 97 Miroslav Janković, Monika Lajhner, Jelena Đorđević, Dragan Popović, Zdravko Janković, Marina Marković, Jovana Zlatković, Darko Kenig, Jelisaveta Belić, Ivan Knežević, Nebojša Muljava COVER ILLUSTRATION XIII GLBT MOVEMENT IN SERBIA 99 Stylized photo of a school desk of one gay secondary school student on which are drawn swastikas, messages “death to fagots”, etc.. However, on the desk someone also wrote: “I’m glad there is someone like me. N. :)” XIV RECOMMENDATIONS 101 THANKS! Members of the Gay Straight Alliance Victims of the violence and discrimination who courageously spoke publicly and reported the incidents Civil Rights Defenders and Fund for an Open Society for financial support to create -

Open-Parliament-Vol

Table of content Open Parliament Newsletter PARLIAMENTARY INSIDER Issue 5 / Vol 5 / March 2019 Introductory remarks 5 Month in the parliament 6 Parliament in numbers 8 OUR HIGHLIGHTS: Analysis of the Open Parliament 9 Introductory remarks Summaries of the laws 11 Opposition’s proposals on the agenda four years after naslovna Law on tourism 11 Law on the Hospitality Industry 13 Open Parliament Analyses Law amending the Law on Plant Protection Products 13 March in the shadow of the parliamentary boycott Law amending the Law on Plant Health 14 Law amending the Law on plant nutrition products and soil conditioners 19 Summaries of the laws Law on Central Population Register 20 Law on Tourism Law proposal on financing Autonomous Province of Vojvodina 22 Law on the Hospitality Industry Law amending the Law on Plant Protection Products Proposal of the Resolution of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia on Vojvodina 25 Law amending the Law on Food Safety Law amending the Law on plant nutrition products and soil conditioners Law on Central Population Register Law proposal on financing Autonomous Province of Vojvodina Proposal of the Resolution of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia on Vojvodina INTRODUCTORY REMARKS Opposition’s proposals on the agenda four years after A part of the opposition MPs carried on with their boycott in March as well, and in the Assembly Hall, the abuse of procedures and discussions on topics unrelated to the agenda continued. The agenda included two proposals from the opposition party League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina MPs. The spring session started with the continued boycott of the opposition, so one fifth of MPs seats remained empty. -

Republic of Serbia

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF SERBIA PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2 April 2017 OSCE/ODIHR NEEDS ASSESSMENT MISSION REPORT 9-10 February 2017 Warsaw 7 March 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................... 1 III. FINDINGS .................................................................................................................... 3 A. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ............................................................................ 3 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM .................................................................. 4 C. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ................................................................................................ 4 D. VOTER REGISTRATION ......................................................................................................... 5 E. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION ................................................................................................. 6 F. ELECTION CAMPAIGN .......................................................................................................... 6 G. CAMPAIGN FINANCE ............................................................................................................ 6 H. MEDIA ................................................................................................................................. -

Parliamentary Insider

Table of content Open Parliament Newsletter PARLIAMENTARY INSIDER Introductory remarks 5 Issue 12 / March - April 2020 From discussing weapons to reviewing the fundamental role of the MPs in the state of emergency 5 Month in the parliament 7 Parliament in numbers 9 OUR HIGHLIGHTS: Analysis of the Open Parliament 11 Women in Parliament: XI Legislature 11 Introductory remarks: Selection of law abstracts 14 From discussing weapons to reviewing the fundamental role Law concerning the confirmation of the Protocol amending the Convention for the of the MPs in the State of Emergencynaslovna Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data 14 Proposal of the Law amending the Law on ID card 16 Open Parliament Analysis Proposal of the Law amending the Law on Road Safety 18 Women in Parliament: XI Legislature Law amending the Law on Local Elections 19 Summaries of the laws Law amending the Law on Election of the Members of Parliament 20 Law concerning the confirmation of the Protocol amending Law amending the Law on Population Protection from the Infectious Diseases 20 the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data Law amending the Law on Local Elections Summaries of the audio reports Strofa, Refren, Replika Law amending the Law on Election of the Members of Parliament 24th episode Law amending the Law on Population Protection from the Infectious Diseases 25th episode 26th episode Audio reports #StrofaRefrenReplika 27th episode 28th episode 29th episode 30th episode 31st episode INTRODUCTORY REMARKS From discussing weapons to reviewing the fundamental role of the MPs in the state of emergency The key highlights of March and April in the Parliament are the reduced activities of the MPs during Spring Session, proclamation of the state of emergency and convening of the first sitting during the state of emergency. -

Programme for Participants

Parliamentary engagement on human rights: Identifying good practices and new opportunities for action Seminar for members of parliamentary human rights committees organized by the Inter-Parliamentary Union in collaboration with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 24 – 26 June 2019, Geneva UN Palais des Nations, Conference Room XXIII BACKGROUND In the last 70 years, starting with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the international community has made great strides in developing new, and fine-tuning existing, international human rights standards. However, this progress has yet to be matched by a similar change on the ground which is why bridging this “implementation gap” has become a priority. Parliaments, in particular their human rights committees, have a critical role to play in the promotion and protection of human rights by turning international human rights obligations into meaningful action at the national level. Increasingly, United Nations human rights mechanisms, most notably the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) and the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), have recognized the potential of parliaments to help ensure better implementation of human rights standards, and have therefore started to include the work of parliaments more systematically in their own deliberations. In turn, parliaments—in particular parliamentary human rights committees—have intensified their efforts to acquire a better understanding of the functioning of UN human rights mechanisms and to contribute directly to their work. The seminar for members of parliamentary human rights committees aims to take stock of where these efforts have brought us to today and to identify good practices and new courses of action.