Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg Interactive Channels 5145 Tropicales 225 The Weather Channel 90 Interactive Dashboard 5146 Mexicana 2 City of Las Vegas Television 230 C-SPAN 92 Interactive Games 5147 Romances 3 NBC 231 C-SPAN2 4 Clark County Television 251 TLC Digital Music Channels PrismTM Complete 5 FOX 255 Travel Channel 5101 Hit List TM 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 265 National Geographic Channel 5102 Hip Hop & R&B Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 7 Universal Sports 271 History 5103 Mix Tape 132 American Life 8 CBS 303 Disney Channel 5104 Dance/Electronica 149 G4 9 LATV 314 Nickelodeon 5105 Rap (uncensored) 153 Chiller 10 PBS 326 Cartoon Network 5106 Hip Hop Classics 157 TV One 11 V-Me 327 Boomerang 5107 Throwback Jamz 161 Sleuth 12 PBS Create 337 Sprout 5108 R&B Classics 173 GSN 13 ABC 361 Lifetime Television 5109 R&B Soul 188 BBC America 14 Mexicanal 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5110 Gospel 189 Current TV 15 Univision 364 Lifetime Real Women 5111 Reggae 195 ION 17 Telefutura 368 Oxygen 5112 Classic Rock 253 Animal Planet 18 QVC 420 QVC 5113 Retro Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 19 Home Shopping Network 422 Home Shopping Network 5114 Rock 258 Science Channel 21 My Network TV 424 ShopNBC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 25 Vegas TV 428 Jewelry Television 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 27 ESPN 451 HGTV 5117 Classic Alternative 272 Biography 28 ESPN2 453 Food Network 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 274 History International 33 CW 503 MTV 5120 Soft Rock 305 Disney XD 39 Telemundo 519 VH1 5121 Pop Hits 315 Nick Too 109 TNT 526 CMT 5122 90s 316 Nicktoons 113 TBS 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5123 80s 320 Nick Jr. -

Everly IPTV Channel Guide 10-7-19.Xlsx

EVERLY IPTV BASIC (continued on back) Standard HD Standard HD 4 KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) 404 CNN 104 CNN 504 9 KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) 409 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 105 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 505 KDINDT2 "IPTV KIDS" 410 MSNBC 107 MSNBC 507 11 KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" 411 CNBC 111 CNBC 511 KEYC "CBS" (MANKATO) 412 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 112 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 512 14 KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) 414 C-SPAN 115 15 KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) 415 C-SPAN2 116 22 KTIVDT2 "CW" KTIVDT2 "CW" 422 NICKELODEON 123 NICKELODEON 523 30 ESPN ESPN 430 NICK JR. 124 31 ESPN NEWS ESPN NEWS 431 NICK TOO 126 32 ESPN CLASSIC NICKTOONS 127 33 ESPNU ESPNU 433 BOOMERANG 129 35 ESPN2 ESPN2 435 CARTOON NETWORK 131 CARTOON NETWORK 531 39 NFL NETWORK NFL NETWORK 439 DISNEY 133 DISNEY 533 43 THE TENNIS CHANNEL THE TENNIS CHANNEL 443 DISNEY JUNIOR 134 DISNEY JUNIOR 534 44 GOLF CHANNEL GOLF CHANNEL 444 DISNEY XD 136 DISNEY XD 536 45 OLYMPIC CHANNEL OLYMPIC CHANNEL 445 FREEFORM 138 FREEFORM 538 47 OUTDOOR CHANNEL OUTDOOR CHANNEL 447 TEEN NICK 140 49 NBC SPORTS CHANNEL NBC SPORTS CHANNEL 449 DISCOVERY FAMILY 143 DISCOVERY FAMILY 543 50 FOX SPORTS 1 FOX SPORTS 1 450 DISCOVERY 144 DISCOVERY 544 51 FOX SPORTS 2 FOX SPORTS 2 451 MOTOR TREND 545 55 FOX SPORTS NORTH FOX SPORTS NORTH 455 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 149 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 549 FOX SPORTS NORTH PLUS 457 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 150 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 550 61 BIG TEN 1 (overflow) BIG TEN 1 (overflow) 461 ANIMAL PLANET 153 -

Channel Lineup January 2018

MyTV CHANNEL LINEUP JANUARY 2018 ON ON ON SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND My64 (WSTR) Cincinnati 11 511 Foundation Pack Kids & Family Music Choice 300-349• 4 • 4 A&E 36 536 4 Music Choice Play 577 Boomerang 284 4 ABC (WCPO) Cincinnati 9 509 4 National Geographic 43 543 4 Cartoon Network 46 546 • 4 Big Ten Network 206 606 NBC (WLWT) Cincinnati 5 505 4 Discovery Family 48 548 4 Beauty iQ 637 Newsy 508 Disney 49 549 • 4 Big Ten Overflow Network 207 NKU 818+ Disney Jr. 50 550 + • 4 Boone County 831 PBS Dayton/Community Access 16 Disney XD 282 682 • 4 Bounce TV 258 QVC 15 515 Nickelodeon 45 545 • 4 Campbell County 805-807, 810-812+ QVC2 244• Nick Jr. 286 686 4 • CBS (WKRC) Cincinnati 12 512 SonLife 265• Nicktoons 285 • 4 Cincinnati 800-804, 860 Sundance TV 227• 627 Teen Nick 287 • 4 COZI TV 290 TBNK 815-817, 819-821+ TV Land 35 535 • 4 C-Span 21 The CW 17 517 Universal Kids 283 C-Span 2 22 The Lebanon Channel/WKET2 6 Movies & Series DayStar 262• The Word Network 263• 4 Discovery Channel 32 532 THIS TV 259• MGM HD 628 ESPN 28 528 4 TLC 57 557 4 STARZEncore 482 4 ESPN2 29 529 Travel Channel 59 559 4 STARZEncore Action 497 4 EVINE Live 245• Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) 18 STARZEncore Action West 499 4 EVINE Too 246• Velocity HD 656 4 STARZEncore Black 494 4 EWTN 264•/97 Waycross 850-855+ STARZEncore Black West 496 4 FidoTV 688 WCET (PBS) Cincinnati 13 513 STARZEncore Classic 488 4 Florence 822+ WKET/Community Access 96 596 4 4 STARZEncore Classic West 490 Food Network 62 562 WKET1 294• 4 4 STARZEncore Suspense 491 FOX (WXIX) Cincinnati 3 503 WKET2 295• STARZEncore Suspense West 493 4 FOX Business Network 269• 669 WPTO (PBS) Oxford 14 STARZEncore Family 479 4 FOX News 66 566 Z Living 636 STARZEncore West 483 4 FOX Sports 1 25 525 STARZEncore Westerns 485 4 FOX Sports 2 219• 619 Variety STARZEncore Westerns West 487 4 FOX Sports Ohio (FSN) 27 527 4 AMC 33 533 FLiX 432 4 FOX Sports Ohio Alt Feed 601 4 Animal Planet 44 544 Showtime 434 435 4 Ft. -

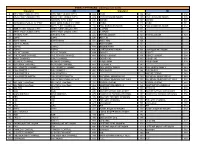

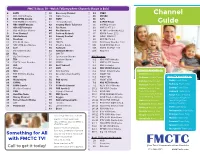

Channel Guide

FMCTC Basic TV - Watch TVEverywhere Channels Shown in Bold 2 ESPN 38 Discovery Channel 84 CNBC Channel 3 CBS KMTV-Omaha 39 WGN America 85 MSNBC 4 FOX KPTM-Omaha 40 HGTV 86 SyFy 5 FOX KDSM-Des Moines 41 History Channel 90 CSPAN-House Guide 6 NBC WOWT-Omaha 42 Country Music Television 91 CSPAN2-Senate 7 ABC KETV-Omaha 43 Fox News 93 KMTV LAFF 3.2 8 CBS KCCI-Des Moines 44 Fox Business 94 KPTM This-Omaha 42.2 9 Food Channel 45 Cartoon Network 95 KDSM Comet 17.2 10 USA Network 46 Comedy Central 96 WOWT COZI 6.2 11 Freeform 47 EWTN 98 KCCI MeTV 8.2 12 PBS KHIN-Iowa 48 FMCTV 100 WHO Iowa Weather 13.2 13 NBC WHO-Des Moines 49 Channel Guide 101 KXVO CHARGE 15.3 14 Golf 50 Hallmark 105 KDSM CHARGE 17.3 15 CW KXVO-Omaha 51 Hallmark Movies 108 KCCI 8.3 16 TLC 52 MAV TV 17 Big Ten Network 53 Sportsman Channel HD Channels 18 TBS 54 Outdoor Channel 3-1 CBS KMTV-Omaha 19 FMCTV Local Weather 55 RFDTV 3-2 KMTV LAFF-Omaha 23 VH1 56 Do It Yourself 3-3 KMTV Escape 24 TV Land 57 OWN 6-1 NBC WOWT-Omaha 25 MTC 58 BTN Overflow 6-2 WOWT COZI-Omaha Digital TV Available In: 26 PBS KYNE-Nebraska 59 Great American Country 6-3 WOWT H&I • Corley-Rural & Town 27 TNT 70 FX 6-4 WOWT ION • Defiance-Rural & Town Basic TV Available In: 28 Nickelodeon 71 FOX Sports 6-5 WOWT STAR • Earling-Rural & Town • Corley-Town Only 29 ESPN2 72 FXX 7-1 ABC KETV-Omaha • Defiance-Town Only 30 ESPN Classic 73 FX Movie Channel 7-2 KETV MeTV-Omaha • Hancock-Rural & Town 31 Weather Channel 74 FOX Sports 2 15-1 CW KXVO-Omaha • Harlan-Parts of Town, • Earling-Town Only 32 CNN 75 Olympic Channel -

XFINITY®TV Channel Line Up

xfirnty XFINITY®TV Channel Line up Effective January 2016 King County/Pierce County/ Snohomish County ~k WA-009 COMCAST 677 Disney Channel HD " 50 Bloomberg TV /\ 679 Nickelodeon HD " 53 FX XFINITY®TV 681 Disney XD HD " 54 TNT A Secondary Audio Programming (SAP) available • Channels in bold are HD 696 Science HD 55 TBS 720 Sprout HD 59 Syfy /\ 109 KCTS HD (PBS) Limited Basic 721 Discovery Family 62 VH1 110 KZJO HD (JOETV) Channel HD 63 MTV 111 KSTW HD (CW) 2 NWCN 64 MTV 2 1121126 KUNS HD (Univision) 3 KWPX-TV ION Digital Economy 66 Bravo /\ 113 KCPQ HD (FOX) 4 KOMO (ABC) 68 HGTV 321 Seattle Channel HD Includes Limited Basic 5 KING (NBC) 70 Golf Channel 322 KCTV-HD 35 Food Network 6 KONG 71 Oxygen 325 KIRO Get TV 37 History /\ 7 KIRO (CBS) 118 Sprout 328 KOMO ThisTV (ABC) 41 Disney Channel /\ 8 Discovery Channel 128 WGN 331 Live Well Network 42 Cartoon Network /\ 9 KCTS (PBS) 149 MoviePlex /\ 334 KBTC-MHz 43 Animal Planet 10 KZJO (JOETV) 150 C-SPAN3 336 KCTS-Create 44 CNN 11 KSTW (CW) 152 Crossings TV 337 KCTS Vme 48 Fox News Channel 12 KBTC (PBS) 162 BBC America /\ 340 Antenna TV 49 truTV 12 KVOS Me TV (Marysvillel 173 ESPN HD 343 KVOS Movies! 51 Lifetime /\ Arlington) 174 ESPN 2 HD 346/738 KUNS (MundoFox) 52 A&E /\ 13 KCPQ (FOX) 183 Esquire 349 Azteca America 56 BET 14 KBCB (IND) 271 Investigation Discovery 350 KFFV Antenna TV 58 USA Network /\ 15 KFFV (IND) 273 National Geographic 351 KFFV KBS World 60 Comedy Central 16 QVC Channel 352 CoziTV 65 E!/\ 17 HSN 275 fyi, 353 KSTW-Decades 67 AMC /\ 18 KWDK (Daystar) 276 H2 599 XFINITY Latino -

TEN Ten Network Holdings Ltd (Administrators

Sale and Recapitalisation of Ten ASX Code: TEN Ten Network Holdings Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) ACN 081 327 068 and Associated Entities (Collectively ‘Ten ’ or the ‘Company’ - refer to Appendix 2) Further to the announcement of July 6, 2017, the Receivers and Managers (Christopher Hill, Philip Carter, David McEvoy of PPB Advisory) with the assistance of its sale advisor Moelis Australia Advisory Pty Ltd undertook a competitive process to identify a suitable party to purchase or recapitalise the Company or the business and assets of the Company. We advise that the Administrators (Mark Korda, Jarrod Villani and Jenny Nettleton of Korda Mentha) and the Receivers and Managers have entered into binding transaction documents with wholly owned entities of CBS Corporation (‘CBS’), a New York Stock Exchange listed corporation (the 'Transaction'). The Transaction contemplates an acquisition of the Company by CBS, which will be effected by way of a refinance of existing secured debt arrangements (including shareholder guarantor fees) in full and a Deed of Company Arrangement (‘DOCA’) that will be put to creditors at the second creditors meeting. Further details on the expected return to creditors and timing of the second creditors meeting will be provided in due course. Note that the Transaction is only subject to certain limited conditions including Foreign Investment Review Board approval, and compulsory transfer of shares in Ten to CBS through a section 444GA process (which will require Australian Securities and Investment Commission relief to permit the transfer and an order made by the Court under section 444GA of the Corporations Act). -

Packages & Channel Lineup

™ ™ ENTERTAINMENT CHOICE ULTIMATE PREMIER PACKAGES & CHANNEL LINEUP ESNE3 456 • • • • Effective 6/17/21 ESPN 206 • • • • ESPN College Extra2 (c only) (Games only) 788-798 • ESPN2 209 • • • • • ENTERTAINMENT • ULTIMATE ESPNEWS 207 • • • • CHOICE™ • PREMIER™ ESPNU 208 • • • EWTN 370 • • • • FLIX® 556 • FM2 (c only) 386 • • Food Network 231 • • • • ™ ™ Fox Business Network 359 • • • • Fox News Channel 360 • • • • ENTERTAINMENT CHOICE ULTIMATE PREMIER FOX Sports 1 219 • • • • A Wealth of Entertainment 387 • • • FOX Sports 2 618 • • A&E 265 • • • • Free Speech TV3 348 • • • • ACC Network 612 • • • Freeform 311 • • • • AccuWeather 361 • • • • Fuse 339 • • • ActionMAX2 (c only) 519 • FX 248 • • • • AMC 254 • • • • FX Movie 258 • • American Heroes Channel 287 • • FXX 259 • • • • Animal Planet 282 • • • • fyi, 266 • • ASPiRE2 (HD only) 381 • • Galavisión 404 • • • • AXS TV2 (HD only) 340 • • • • GEB America3 363 • • • • BabyFirst TV3 293 • • • • GOD TV3 365 • • • • BBC America 264 • • • • Golf Channel 218 • • 2 c BBC World News ( only) 346 • • Great American Country (GAC) 326 • • BET 329 • • • • GSN 233 • • • BET HER 330 • • Hallmark Channel 312 • • • • BET West HD2 (c only) 329-1 2 • • • • Hallmark Movies & Mysteries (c only) 565 • • Big Ten Network 610 2 • • • HBO Comedy HD (c only) 506 • 2 Black News Channel (c only) 342 • • • • HBO East 501 • Bloomberg TV 353 • • • • HBO Family East 507 • Boomerang 298 • • • • HBO Family West 508 • Bravo 237 • • • • HBO Latino3 511 • BYUtv 374 • • • • HBO Signature 503 • C-SPAN2 351 • • • • HBO West 504 • -

XFINITY® TV Channel Lineup

XFINITY® TV Channel Lineup Somerville, MA C-103 | 05.13 51 NESN 837 A&E HD 852 Comcast SportsNet HD Limited Basic 52 Comcast SportsNet 841 Fox News HD 854 Food Network HD 54 BET 842 CNN HD 855 Spike TV HD 2 WGBH-2 (PBS) / HD 802 55 Spike TV 854 Food Network HD 858 Comedy Central HD 3 Public Access 57 Bravo 859 AMC HD 859 AMC HD 4 WBZ-4 (CBS) / HD 804 59 AMC 863 Animal Planet HD 860 Cartoon Network HD 5 WCVB-5 (ABC) / HD 805 60 Cartoon Network 872 History HD 862 Syfy HD 6 NECN 61 Comedy Central 905 BET HD 863 Animal Planet HD 7 WHDH-7 (NBC) / HD 807 62 Syfy 906 HSN HD 865 NBC Sports Network HD 8 HSN 63 Animal Planet 907 Hallmark HD 867 TLC HD 9 WBPX-68 (ION) / HD 803 64 TV Land 910 H2 HD 872 History HD 10 WWDP-DT 66 History 901 MSNBC HD 67 Travel Channel 902 truTV HD 12 WLVI-56 (CW) / HD 808 13 WFXT-25 (FOX) / HD 806 69 Golf Channel Digital Starter 905 BET HD 14 WSBK myTV38 (MyTV) / 186 truTV (Includes Limited Basic and 906 HSN HD HD 814 208 Hallmark Channel Expanded Basic) 907 Hallmark HD 15 Educational Access 234 Inspirational Network 908 GMC HD 16 WGBX-44 (PBS) / HD 801 238 EWTN 909 Investigation Discovery HD 251 MSNBC 1 On Demand 910 H2 HD 17 WUNI-27 (UNI) / HD 816 42/246 Bloomberg Television 18 WBIN (IND) / HD 811 270 Lifetime Movie Network 916 Bloomberg Television HD 284 Fox Business Network 182 TV Guide Entertainment 920 BBC America HD 19 WNEU-60 (Telemundo) / 199 Hallmark Movie Channel HD 815 200 MoviePlex 20 WMFP-62 (IND) / HD 813 Family Tier 211 style. -

NCC Media Price Vs

GET CONNECTED • GET SMART • BE EVERYWHERE • GET CONNECTED • GET SMART • BE EVERYWHERE • GET CONNECTED • GET SMART Table of contents INTRODUCTION ROI DRIVEN Broadcast 2 Introduction Letter 35 Cable 3 Cable: The Media of Choice Reach More Consumers; More Effective Frequency GET CONNECTED 39 5 About NCC Media Price vs. Consumer Value 6 Cable, Satellite, and TARGETED Telco Interconnected 8 Connecting Advertisers to 41 Geo-Targeting Consumers in Cable Programming State Market County System GET SMART 11 SMART: The Acronym for Success in Cable 43 Targeting Multicultural Consumers SIMPLE 45 Micro-Targeting at the Cable System Level 13 eBusiness Agency Support MARKET FOCUSED BE EVERYWHERE 15 Viewer Migration to Cable 47 NCC Online Media 16 Broadcast Prime and Local 49 News Viewing Trends The Right Sites for your 20 Complementing Network Brand in Every Market Cable with Spot Cable 50 NCC Interactive Media: iTV and VOD ADAPTABLE 51 Mobile Marketing 51 23 The Right Cable Programming for Your Brand in Every Market NCC CONSULTATIVE RESOURCES 52 Investment Grade Research, Programming and Marketing Analysis 30 Reach Sports Enthusiasts More Effectively 54 The Company We Keep 55 Top 10 Key Media Buying and Planning Guidelines for Spot Television 32 Cable Program Sponsorships and Sweepstakes 1 GET CONNECTED • GET SMART • BE EVERYWHERE • GET CONNECTED • GET SMART • BE EVERYWHERE • GET CONNECTED • GET SMART NCC Media and our owners—Comcast, Time Warner Cable and Cox Media— have implemented a remarkable new set of strategic growth initiatives and partnerships. Among these recent developments, the most important and fascinating one is the forming of alliances between NCC, cable operators and satellite and telco programming distributors, including DIRECTV, AT&T U-verse and VERIZON FiOS. -

How Murdoch Outfoxed CBS V3.0

How Rupert Murdoch Outfoxed Larry Tisch: Ten Enduring Lessons from the Negotiations that Wrested the NFL from CBS James K. Sebenius Working Paper 19-098 How Rupert Murdoch Outfoxed Larry Tisch: Ten Enduring Lessons from the Negotiations that Wrested the NFL from CBS James K. Sebenius Harvard Business School Working Paper 19-098 Copyright © 2019 by James K. Sebenius Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. How Rupert Murdoch Outfoxed Larry Tisch: Ten Enduring Lessons from the Negotiations that Wrested the NFL from CBS By James K. Sebenius,* March 7, 2019 Abstract A remarkable 1993 negotiation rocked the world of American football with aftershocks that have directly shaped today’s entertainment and media landscapes, and even our polarized politics. In December of that year, Rupert Murdoch’s fledgling Fox Network unexpectedly displaced longtime incumbent CBS as the host of the National Football League’s flagship programming. Fox’s negotiating success seemed most unlikely given that CBS had regularly renewed these NFL rights since 1956, enjoyed a good relationship with the NFL, sported an acclaimed broadcast unit, and had affiliates in virtually all important U.S. markets. Yet acquisition of these NFL rights directly enabled the expansion Fox, then a minor broadcaster, into the media behemoth of today. For many observers, Fox’s NFL “heist” looked like the result of a simple move: Fox offered more money than CBS. A closer analysis, however, suggests a far more complex reality with ten broader lessons for negotiators facing challenging situations. -

June 17, 2019 the Honorable Makan Delrahim Assistant Attorney General Antitrust Division U.S. Department of Justice 450 Fifth S

June 17, 2019 The Honorable Makan Delrahim Assistant Attorney General Antitrust Division U.S. Department of Justice 450 Fifth Street, NW Washington DC 20530 Via Email to [email protected] Re: Public Workshop on Competition in Television and Digital Advertising Dear Assistant Attorney General Delrahim and Division Staff: The National Association of Broadcasters1 appreciated the opportunity to participate in the Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division’s recent public workshop on Competition in Television and Digital Advertising.2 As NAB and other broadcasters observed during the workshop, the DOJ’s definition of the relevant markets for analyzing proposed broadcast television mergers is critically important. Defining the market as one in which only local television stations compete unjustifiably limits the ability of television broadcasters to enter efficient combinations and realize economies of scale and scope. These limitations make it increasingly difficult for broadcasters to compete effectively with much larger entities that face fewer regulatory restrictions and to continue providing free over-the-air services to local viewers, including both entertainment and vital coverage of local news, emergencies and severe weather. The presentations of several workshop participants demonstrated that broadcasters, multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) and digital video platforms, among other outlets, compete head-to-head for advertising dollars. Among other things, panelists 1 The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) is a nonprofit association that advocates on behalf of local radio and television stations and broadcast networks before Congress, the Federal Communications Commission and other federal agencies, and the courts. 2 See DOJ Antitrust Division, Public Workshop on Competition in Television and Digital Advertising, May 2-3, 2019, https://www.justice.gov/atr/public-workshop-competition- television-and-digital-advertising. -

American Primacy and the Global Media

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Chalaby, J. (2016). Drama without drama: The late rise of scripted TV formats. Television & New Media, 17(1), pp. 3-20. doi: 10.1177/1527476414561089 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/5818/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1527476414561089 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Drama without drama: The late rise of scripted TV formats Author’s name and address: Professor Jean K. Chalaby Department of Sociology City University London London EC1V 0HB Tel: 020 7040 0151 Fax: 020 7040 8558 Email: [email protected] Author biography: Jean K. Chalaby is Professor of International Communication and Head of Sociology at City University London. He is the author of The Invention of Journalism (1998), The de Gaulle Presidency and the Media (2002) and Transnational Television in Europe: Reconfiguring Global Communications Networks (2009).