1 Relatives in Residence: the Importance of Fathers And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

V15.4 Code Table Listing

V.15.4 Code Table Listing -- SSIS.RELATION Sort = RELATION_ID Relation_ID Relation_Desc Person1_ NEU_DESC Person2_ NEU_DESC Last Chgd Dt 1 Adoptive parent - adoptive child Adoptive parent Adoptive child 03/01/2003 2 Aunt/uncle - niece/nephew Aunt/uncle Niece/Nephew 03/01/2003 4 Birth parent - birth child Birth parent Birth child 01/03/2008 5 Brother/sister-in-law - brother/sister-in-law Brother/sister-in-law Brother/Sister-in-law 03/01/2003 9 Cousin - cousin Cousin Cousin 03/01/2003 10 Ex-spouse - ex-spouse Ex-spouse Ex-spouse 03/01/2003 11 Kin (tribal or ethnic)/previous foster parent - Kin Kin (tribal or ethnic)/previous Kin (tribal or ethnic)/previous 08/27/2015 (tribal or ethnic)/previous foster child foster parent foster child 14 Father/mother-in-law - son/daughter-in-law Father/mother-in-law Son/daughter-in-law 03/01/2003 15 Previous foster parent, non-relative - previous Previous foster parent, Previous foster child 11/24/2008 foster child non-relative 16 Foster parent - foster child Foster parent Foster child 03/01/2003 18 Grandparent - grandchild Grandparent Grandchild 03/01/2003 19 Guardian ad litem - client Guardian ad litem Client 07/31/2003 21 Legal guardian - ward Legal guardian Ward 03/01/2003 25 Other non-relative - other non-relative Other non-relative Other non-relative 03/01/2003 26 Other relative - Other relative Other relative Other relative 03/01/2003 27 Parent's partner - partner's child Parent's partner Partner's child 03/01/2003 28 Partner - partner Partner Partner 03/01/2003 31 Sibling - sibling Sibling Sibling -

Medical Student Research Project

Medical Student Research Project Supported by The John Lachman Orthopedic Research Fund and Supervised by the Orthopedic Department’s Office of Clinical Trials Acute Management of Open Long Bone Fractures: Clinical Practice Guidelines ELIZABETH ZIELINSKI, BS;1 SAQIB REHMAN, MD2 1Temple University School of Medicine; 2Temple University Hospital, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Philadelphia, PA syndrome,1, 2 often resulting in loss of function of the limb. Abstract Infection rates can range from 0–50% depending on fracture Introduction: The acute management of an open frac- severity and location2–5 and nonunion rates are reported at an ture aims to promote bone and wound healing through a incidence of 18–29%.6, 7 Historically, amputation of the frac- series of key steps; however, lack of standardization in tured limb and mortality were commonly associated with these steps prior to definitive treatment may contribute to open fractures.8, 9 However, due to developments in its man- complications. agement, outcomes for open fractures have generally Methods: A literature review was conducted to deter- improved, as limbs are often salvaged and patients can retain mine the best practice in the acute management of open function of the injured extremity. Despite generalized stan- long bone fractures to be implemented at Temple Univer- dards for open fracture treatment, there remains variation sity Hospital, with a primary focus on prophylactic anti- and controversy over the initial management of open frac- biotic administration, local antibiotic delivery, time to tures, which may contribute to complications following debridement and irrigation techniques. treatment. Results: A computerized search yielded 2,037 results, Open fractures occur when the fractured bone penetrates of which a total of 21 articles were isolated and reviewed through the skin, involving damage to the bone and soft tis- based on the study criteria. -

BACK to the BEST INTERESTS of the CHILD 2Nd Edition

POLICY MONOGRAPH BACK TO THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE CHILD 2nd Edition TOWARDS A REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION OF JOINT RESIDENCE Yuri Joakimidis BACK TO THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE CHILD TOWARDS A REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION OF JOINT RESIDENCE Although the dispute is symbolized by a 'versus' which signifies two adverse parties at opposite poles of a line, there is in fact a third party whose interests and rights make of the line a triangle. That person, the child who is not an official party to the lawsuit but whose well- being is in the eye of the controversy, has a right to shared parenting when both are equally suited to provide it. Inherent in the express public policy is a recognition of the child's right to equal access and opportunity with both parents, the right to be guided and nurtured by both parents, the right to have major decisions made by the application of both parents' wisdom, judgement and experience. The child does not forfeit these rights when the parents divorce." Presiding Judge Dorothy T. Beasley, Georgia Court of Appeals, "In the Interest of A.R.B., a Child," July 2, 1993 A PAPER COMPILED BY THE JOINT PARENTING ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Executive Summary................................................................................................... 5 Overview.................................................................................................................... 7 The Solomon Parable ................................................................................................ 8 The Hearing............................................................................................................ -

Living Arrangements of Children: 1996

Living Arrangements of Children 1996 Issued April 2001 Household Economic Studies P70-74 number of children growing up in various What’s in this Report? family situations.1 Current INTRODUCTION AND HIGHLIGHTS Population As in the earlier survey, detailed information Reports LIVING ARRANGEMENTS OF CHILDREN — was obtained on each person’s relationship to AN OVERVIEW every other person in the household, permit- By Jason Fields THE TRADITIONAL NUCLEAR FAMILY ting the identification of many types of rela- tives, and parent-child and sibling relation- CHILDREN LIVING WITH TWO PARENTS: ships. This report describes family situations BIOLOGICAL, STEP-, AND ADOPTIVE beyond the traditional nuclear family of par- CHILDREN LIVING WITH UNMARRIED ents and their children and includes discus- PARENTS sions of extended family households with CHILDREN IN BLENDED FAMILIES relatives and nonrelatives who may contrib- ute substantially to a child’s development ADOPTED CHILDREN and to the household’s economic well-being. CHILDREN WITH SIBLINGS This report also examines the degree to THE EXTENDED FAMILY HOUSEHOLD which children are living in single-parent Relatives in Extended Families families, with stepparents and adoptive par- Multigenerational Households and ents, or with no parents and in the care of Children With Grandparents another relative or guardian. Of special inter- HISTORICAL TRENDS est in this report are new estimates of chil- dren living with unmarried cohabiting par- ents (either with both of their biological INTRODUCTION AND HIGHLIGHTS parents who are not married to each other, or Children live in a variety of family arrange- with a parent and an unmarried partner who ments, some of which are complex, as a is not the child’s biological parent — see defi- consequence of the marriage, divorce, and nitions box for descriptions of these terms). -

Family Registration Form

FAMILY REGISTRATION FORM An NCHA member may allow certain members of his/her immediate family (as defined in that rule) to show a horse owned by that member in NCHA amateur and non- professional events. If the horse owner/member wishes for someone in his/her immediate family to show the horse owner/member’s horse under the provisions of Rule 51.a.4, it is the responsibility of the horse owner/ member to complete this form and file it with the NCHA prior to any show in which an immediate family member will be showing any horse owned by the horse owner/member. Any horse owner/member filing this form is also responsible for filing with the NCHA any updates necessary to insure that this form to is accurate and up to date. If this completed form is not on file with the NCHA, no one other than the horse owner may show that horse in any amateur or non-pro classes. Member/Owner Name: ___________________________ Member #: _______ ___ (Please Print) Horses: Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ Name as it appears on Breed registry: ____________________________________Reg#____________ IMMEDIATE FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS: Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Name: ______________ Member #: __________ Relationship: _________ Date: Signature: ________________________________________________________ RECEIVED BY NCHA: REFERENCE SHEET FOR FAMILY OWNED HORSE RULE The following chart is to assist in the application of the NCHA’s new Family Owned Horse Rule. -

The Experience and Expression of Emotion Within Stepsibling

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Faculty Scholarship – Communication Communication 5-2010 The Experience and Expression of Emotion within Stepsibling Relationships: Politeness of Expression and Stepfamily Functioning Emily Lamb Normand Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/comm_facp Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lamb Normand, Emily, "The Experience and Expression of Emotion within Stepsibling Relationships: Politeness of Expression and Stepfamily Functioning" (2010). Faculty Scholarship – Communication. 2. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/comm_facp/2 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship – Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPERIENCE AND EXPRESSION OF EMOTION WITHIN STEPSIBLING RELATIONSHIPS: POLITENESS OF EXPRESSION AND STEPFAMILY FUNCTIONING by Emily Lamb Normand A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Professors Dawn O. Braithwaite and Jordan E. Soliz Lincoln, Nebraska May 2010 THE EXPERIENCE AND EXPRESSION OF EMOTION WITHIN STEPSIBLING RELATIONSHIPS: POLITENESS OF EXPRESSION AND STEPFAMILY FUNCTIONING Emily Lamb Normand, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisors: Dawn O. Braithwaite and Jordan E. Soliz While scholars agree there are emotional challenges associated with the divorce and remarriage process, little is known about how stepsiblings interact and manage the experience and expression of emotion within their stepfamily. -

Ethics Presentation

Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do. POTTER STEWART U.S. Supreme Court 1958-1981 What is your current position with your district or school? A. Board Member B. Superintendent/Administrator 0% 0% 0% 0% C. Other Other Administrator Board Secretary Business Manager/Finance How long have you been in your current position? A. < 1 year B. 1-4 years C. 5-10 years 0% 0% 0% 0% D. > 10 years < 1 year 1-4 years 5-10 years > 10 years Have you ever worked with the OGEC on an ethics complaint? A. Yes B. No C. No, but we should have 0% 0% 0% 0% D. Prefer not to answer < 1 year 1-4 years 5-10 years > 10 years RELATIVE Spouse Sibling, Stepsibling Parent Son/Daughter-in-law of the Public Stepparent Legal support obligation Official Child Receives benefits Win Lose Cheer Boo Silence Spouse Sibling, Stepsibling Parent Son/Daughter-in-law of the spouse Stepparent of the Public Child Official Win Lose Cheer Boo Silence SPOUSE PARENT STEPPARENT CHILD SIBLING STEPSIBLING SON-IN-LAW DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SUPPORT OBLIGATION* BENEFITS* STEPSON SPOUSE PARENT STEPPARENT STEPSON CHILD SIBLING STEPSIBLING SON-IN-LAW DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SUPPORT OBLIGATION* BENEFITS* SPOUSE PARENT STEPPARENT STEPSON (OF SPOUSE) CHILD SIBLING STEPSIBLING SON-IN-LAW DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SUPPORT OBLIGATION* BENEFITS* MOTHER-IN-LAW SPOUSE PARENT STEPPARENT CHILD SIBLING STEPSIBLING SON-IN-LAW DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SUPPORT OBLIGATION* BENEFITS* SPOUSE (OF SPOUSE) PARENT STEPPARENT CHILD SIBLING STEPSIBLING SON-IN-LAW DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SUPPORT OBLIGATION* -

Ministering to Students in Stepfamilies

MINISTERING TO STUDENTS IN STEPFAMILIES DID YOU KNOW? DID YOU KNOW? One-third of all students in the US will have a stepparent by age 18 (50% will at some point in their lifetime).* Stepfamilies can be a blessing to kids. 100 million Americans have a stepparent relationship (i.e., stepparent, stepsibling, or stepchild) and 40% of families are blended families. Nontraditional is the new traditional family. WATCH OUR VIDEO The Blended Familiy: On average, it takes more time for a child to adjust to a parent’s Help and Hope remarriage than to the original parental divorce. on YouTube: We used to talk about the impact of parental divorce on Youtube.com/user/ children; now we are concerned with the impact of serial marital FamilyLifeBlended transitions: 29% of children have experienced two or more mother breakups . by the age of 15. WHAT IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT OF SERIAL MARITAL TRANSITIONS ON STUDENTS? Lower economic status, lower academic performance, lower emotional well-being (e.g., depression); less connected to their parents; more behavioral problems (including aggressive and delinquent behavior); have sex at an earlier age and are more likely to have their first child out-of-wedlock (51%). Lower confidence in the institution of marriage (which is currently visible in the high rate of cohabitation and stay-over relationships); delays marriage, but doesn’t delay having a child. When they do marry, they divorce more quickly and at a higher rate. * Statistical references available at smartstepfamilies.com/view/statistics MINISTERING TO STUDENTS IN STEPFAMILIES FamilyLife.com/Blended | 1 WHAT IS THE SPIRITUAL IMPACT ON STUDENTS OF MULTIPLE PARENT The family in part is FIGURES MOVING IN AND OUT OF designed by God to be an incubator of faith for THE HOME? children. -

Between a Nuclear Family and a Stepfamily: Growing up with Married Biological Parents and Older Half-Siblings

BETWEEN A NUCLEAR FAMILY AND A STEPFAMILY: GROWING UP WITH MARRIED BIOLOGICAL PARENTS AND OLDER HALF- SIBLINGS _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri–Columbia _______________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by CAROLINE SANNER Dr. Marilyn Coleman, Dissertation Supervisor Dr. Lawrence Ganong, Dissertation Supervisor JULY 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled BETWEEN A NUCLEAR FAMILY AND A STEPFAMILY: GROWING UP WITH MARRIED BIOLOGICAL PARENTS AND OLDER HALF-SIBLINGS presented by Caroline Sanner, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________ Professor Marilyn Coleman ____________________________________ Professor Lawrence Ganong ____________________________________ Professor Sarah Killoren ____________________________________ Professor Tola Pearce DEDICATIONS To Dad. All that I have accomplished in life is because of you. You built me a ladder and a safety net, and you were there, always, to help me climb or to break my fall. Your hard work, sacrifice, and unconditional love are the cornerstones of my life. You are my hero, and I love you always. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many. First, to my academic advisors, Drs. Marilyn Coleman and Larry Ganong. I cannot begin to express the scope of my gratitude for your investment in my development as a scholar. Thank you for encouraging me, challenging me, advocating for me, and opening doors of opportunity at every corner. Our many meetings at the kitchen table, where life and research were discussed over coffee, will always be near and dear to my heart. -

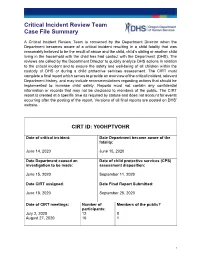

Critical Incident Review Team Case File Summary

Critical Incident Review Team Case File Summary A Critical Incident Review Team is convened by the Department Director when the Department becomes aware of a critical incident resulting in a child fatality that was reasonably believed to be the result of abuse and the child, child’s sibling or another child living in the household with the child has had contact with the Department (DHS). The reviews are called by the Department Director to quickly analyze DHS actions in relation to the critical incident and to ensure the safety and well-being of all children within the custody of DHS or during a child protective services assessment. The CIRT must complete a final report which serves to provide an overview of the critical incident, relevant Department history, and may include recommendations regarding actions that should be implemented to increase child safety. Reports must not contain any confidential information or records that may not be disclosed to members of the public. The CIRT report is created at a specific time as required by statute and does not account for events occurring after the posting of the report. Versions of all final reports are posted on DHS’ website. CIRT ID: Y0OHPTVOHR Date of critical incident: Date Department became aware of the fatality: June 14, 2020 June 15, 2020 Date Department caused an Date of child protective services (CPS) investigation to be made: assessment disposition: June 15, 2020 September 11, 2020 Date CIRT assigned: Date Final Report Submitted: June 18, 2020 September 25, 2020 Date of CIRT meetings: Number of Members of the public? participants: July 2, 2020 12 0 August 27, 2020 16 1 1 Critical Incident Review Team Case File Summary Description of the critical incident and Department contacts regarding the critical incident: Date of report: Allegation(s): Disposition(s): June 15, 2020 Assignment decision: Neglect by Father Unfounded Within 72 Hours On June 15, 2020, the Department received a report regarding the death of a15-year-old child. -

Sibling Relationships in Remarried Families

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2004 Sibling relationships in remarried families Monique C. Diderich Balsam University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Balsam, Monique C. Diderich, "Sibling relationships in remarried families" (2004). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2614. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/11qa-57n8 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIBLING RELATIONSHIPS IN REMARRIED FAMILIES by Monique C. Diderich Balsam Masters of Arts University of Groningen, The Netherlands 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in the Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3194247 Copyright 2005 by Balsam, Monique 0. Diderich All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.