Smokeless Tobacco Use and Circulatory Disease Risk: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed from the California Tobacco Directory by Brand

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Brand Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed #117 - RYO National Tobacco Company 10/21/2011 5/6/05 Man. Change from RBJ to National Tobacco Company 10/20's (ten-twenty's) M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 2/2/05 Man. Name change from Dhanraj Imports, Inc. 10/20's (ten-twenty's) - RYO M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 1st Choice R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Removed 5/2/08; Reinstated 7/11/08 32 Degrees General Tobacco 2/28/2010 4 Aces - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/12/2010 A Touch of Clove Sherman 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. Inc. 9/25/2009 AB Rimboche' - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Ace King Maker Marketing 5/21/2020 All American Value Philip Morris, USA 5/5/2006 All Star Liberty Brands, LLC 5/5/2006 Alpine Philip Morris, USA 8/14/2013 Removed 5/4/07; Reinstated 5/8/09 Always Save Liberty Brands, LLC 5/4/2007 American R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/6/2005 American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC 9/22/2015 American Blend Mac Baren Tobacco Company 5/4/2007 American Harvest Sandia Tobacco Manufacturers, Inc. 8/31/2016 American Harvest - RYO Truth & Liberty Manufacturing 8/2/2016 American Liberty Les Tabacs Spokan 5/12/2006 Amphora - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/18/2011 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Arango Sportsman - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Arbo - RYO VCT 5/4/2007 Ashford Von Eicken Group 5/8/2009 Ashford - RYO Von Eicken Group 12/23/2011 Athey (Old Timer's) Daughters & Ryan, Inc. -

Participating Manufacturers

PARTICIPATING MANUFACTURERS under the Master Settlement Agreement as of June 12, 2015 The following list of brand name tobacco products sold in the United States by Participating Manufacturers has been prepared based on information provided to NAAG by the Participating Manufacturers. NAAG does not assume responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of this information. This list should not and cannot be used to determine whether particular tobacco products are legal for sale in any particular State. Retailers should consult their respective State laws and directories in determining which brands, brand families, or brand styles are legal for sale. Anderson Tobacco Company, LLC SPM from 11/05/2003 – 2/15/2007 Deleted as SPM- no longer in existence Bekenton, S.A. SPM since 6/25/2003 Designated Representatives: Dennis Edward Bruce Esq. Bekenton S.A. 690 Lincoln Road, Suite 303 Miami Beach, Florida 33139 Phone: (888) 672-4991 Fax: (800) 887-1723 Brands: Canary Islands Cigar Co. SPM since 9/26/2003* Designated Representatives: Roberto F. Fleitas, Esquire Federico González de Aledo y Buergo 782 N.W. Lejeune Road Fabrica Record Suite 530 Barrio Chamberi S/N Miami, Florida 33126 Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain Telephone: (305) 442-1439 Telephone: 011-34-922-10-13-66 Facsimile: (305) 442-9944 Facsimile: 011-34-922-20-03-61 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] * On September 26, 2003 the Settling States entered into a Forbearance Agreement with Tabacos de Canarias S.L. (“CITA”) and its wholly-owned subsidiary Canary Island Cigar Co. (“CIC”), and approved Amendment 22 to the Master Settlement Agreement, as a result of which CIC assumed all unsatisfied MSA payment obligations for CITA-made cigarettes sold in the United States from 1999 - 2002 and became a Participating Manufacturer for all CITA-made cigarettes sold in the United States from 2003 forward. -

Nicotine, Tar, and Mutagenicity Of

Journal of Health Science, 55(3) 421–427 (2009) 421 Nicotine, Tar, and Mutagenicity of Mainstream Smoke Generated by Machine Smoking with International Organization for Standardization and Health Canada Intense Regimens of Major Japanese Cigarette Brands Osamu Endo,∗,a Mariko Matsumoto,b Yohei Inaba,b Kazutoshi Sugita,c Daisuke Nakajima,d Sumio Goto,a Hiromitsu Ogata,b and Gen Suzukib aSchool of Life and Environmental Science, Azabu University, 1–17–71 Fuchinobe, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 229–8501, Japan, bDepartment of Environmental Health National Institute of Public Health, 2–3–6 Minami, Wako, Saitama 351–0197, Japan, cAnalysis Division Mitsubishi Chemical Analytech Co., Ltd., 8–5–1 Chuo, Ami-cho, Inashiki-gun, Ibaraki 300–0332, Japan and dResearch Center for Enviromental Risk National Institute for Environmental Studies, 16–2 Onogawa, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0053, Japan (Received February 4, 2009; Accepted March 12, 2009; Published online March 31, 2009) Based upon the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the World Health Organization (WHO) hasrecommended that health authorities disclose toxicological properties of cigarette mainstream smoke (MSS) obtained not only according to US Federal Trade Commission (FTC)/International Organization for Standardization (ISO) conditions but also by more intense conditions such as the Health Canada Intense (HCI) condition. This is because smokers are believed to smoke more intensely than machine smoking under the ISO regimen. Because there are no previous reports on the toxicological properties of MSS of Japanese cigarettes under the HCI condition, we determined nicotine and water contents by gas chromatography (GC-MS and GC/Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD)) for three product lots each of the ten bestselling brands of Japanese cigarettes following the WHO protocol. -

JT Applies to Amend Retail Prices of Tobacco Products in Japan in Response to a Planned Excise Tax Increase

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tokyo, July 30, 2021 JT Applies to Amend Retail Prices of Tobacco Products in Japan in Response to a Planned Excise Tax Increase Japan Tobacco Inc. (JT) (TSE:2914) today announces that it has applied to the Ministry of Finance for approval* to amend the retail prices of its tobacco products in Japan in conjunction with the planned excise tax increase on October 1, 2021. The Company has applied for the retail price amendment for a total of 173 products, including 127 cigarette products, 18 cigarillo products, three pipe tobacco products, three cut tobacco products, 22 snuff tobacco products. The Japanese domestic tobacco market continues to experience decreasing sales volumes due to structural factors including the aging and declining adult population together with increasingly stringent smoking restrictions. As a result, the costs for maintaining the product quality and services are rising. Under these circumstances, while JT has been implementing cost optimization measures in line with a projected further decline of sales volume, it has become even more challenging to maintain the same quality and services that meet our consumer’s satisfaction. In this context, JT has applied to amend the retail prices of cigarettes, which exceeds the excise tax hike of cigarettes (1.0 yen per stick), revised tax structure for light weight cigarillos, while taking into account further increases in costs. JT has decided to amend the retail prices of its tobacco products, however such increase varies among different brands and products, to ensure that the quality of each product will be maintained and that consumer expectations continue to be met. -

Analysis of a Tobacco Vector and Its Actions in China: the Activities of Japan Tobacco Peisen He1,2, Takeaki Takeuchi1*, Eiji Yano1

He et al. Tobacco Induced Diseases 2010, 8:13 http://www.tobaccoinduceddiseases.com/content/8/1/13 REVIEW Open Access Analysis of a tobacco vector and its actions in China: the activities of Japan tobacco Peisen He1,2, Takeaki Takeuchi1*, Eiji Yano1 Abstract Japan Tobacco (JT) is the third largest tobacco company in the world, and China, the world’s largest tobacco consumer, is one of the most important targets for JT. To provide information for tobacco control, we reviewed and analyzed JT and its tactics and strategies in the Chinese market mainly by systematic examination of documents which are made available in the University of California, San Francisco Legacy Tobacco Documents Library. As a result, JT has had a special interest to expand sales of its cigarettes in the Chinese market. Introduction 25.7% of Japanese adults smoke [4]. Besides, the 1987 Smoking is a particular challenge for public health suspension of import tariffs on cigarettes led to rapidly because unlike many other pathogens, this leading cause increased competition in JT’s domestic tobacco market, of morbidity and mortality worldwide continues to be which decreased JT’s sales and market share. To combat actively promoted by large multinational corporations the increased competitive pressures, JT has become and governments. Previous writers have described the more sophisticated and focused in their marketing activities of the two largest transnational tobacco cor- efforts, transforming the company from a Japanese porations (TTC) as summarized later. In this paper we cigarette “manufacturer/distributor” to an International report on the activities of Japan Tobacco (JT), the third cigarette “manufacturer/marketer”[5,6]. -

Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20580 Division of Advertising Practices May23,2008 MEMORANDUM TO: Public Records Office of the Secretary FROM: Sallie Schools Division of Advertising Practices SUBJECT: Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No. P854505 Please place the attached documents on the public record in the above-captioned matter. 1. August 16, 2007letter from Joseph T. Wong Esq. on behalf of Konci G & D Management Group (USA) Inc. to Sallie Schools. 2. September 4, 2007letter from Mary K. Engle to Joseph T. Wong Esq. on behalf of Konci G & D Management Group (USA) Inc. 3. August 20, 2007 letter from Hoo Tjhiang Han, Kretek International, to Sallie Schools. 4. September 5, 2007 letter from Mary K. Engle to Hoo Tjhiang Han, Kretek International. 5. September 6, 2007 letter from Hoo Tjhiang Han, Kretek International, to Sallie Schools. 6. September 7, 2007 letter from Mary K. Engle to Hoo Tjhiang Han, Kretek International. 7. August 23, 2007letter from Craig A. Koenigs on behalf of European Cigarette Imports, Inc. to Mary K. Engle. 8. September 10, 2007letter from Mary K. Engle to Craig A. Koenigs on behalf of European Cigarette Imports, Inc. 9. August 22, 2007 letter from Barry M. Boren on behalf of Tantus Tobacco, LLC to Mary K. Engle. 10. September 13, 2007 letter from Mary K. Engle to Barry M. Boren on behalf of Tantus Tobacco, LLC. 1 Public Records May23, 2008 Page 2 11. September 7, 2007 letter from Karen Kamperman, Tobacco Holdings, Inc. to Mary K. Engle. 12. September 13, 2007 letter from Mary K. -

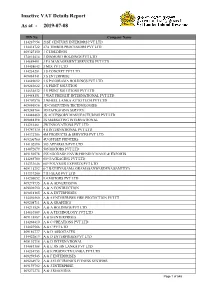

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Tobacco Industry Research Analysts COMMENT

27 July 2016 Asia Pacific/Japan Equity Research Tobacco (Personal Products (Japan)) / MARKET WEIGHT Tobacco industry Research Analysts COMMENT Masashi Mori 81 3 4550 9695 [email protected] Examining the state of Japan’s “heat-not-burn cigarette” market ■ Two products in focus: In Japan’s cigarette market, much of the focus at present is on two type of “heat-not-burn cigarette.” One is iQOS, from Philip Morris International (PMI). This product has made strong gains in market share since going on sale nationwide this April. The other product is Ploom TECH, launched on a trial basis by Japan Tobacco (JT, 2914) in March. For now, iQOS is garnering much of the attention, having launched before Ploom TECH. That said, both products are gaining in popularity and are constantly in short supply. Recognition is growing rapidly for this new genre known as heat-not-burn cigarettes, and we expect market penetration to accelerate. While it is too early to forecast the future for these products, we think they have the potential to become game-changers. In this report, we outline the situation at present. ■ PMI’s 2Q results: Announced on 19 July US time, PMI’s 2Q results served to underscore iQOS' growing popularity. In Japan, iQOS (HeatSticks) reached a national share 2.2% (2.7% in the final week of June), up from 0.8% in 1Q. As positives, PMI noted that (1) the device is now cannibalizing about 35% of the company's cigarette portfolio in Japan, down from around 40% as of September 2015; and (2) many smokers are "up-trading" to iQOS from cheaper brands. -

Contraband Tobacco on Post-Secondary Campuses in Ontario

Contraband Tobacco on Post-Secondary Campuses in Ontario Meagan Barkans, BHSc Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, Applied Health Science (Community Health) Supervisor: Kelli-an Lawrance, PhD Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario Meagan Barkans © August, 2010 Abstract In Ontario 27% of young adults smoke, and annual surveillance data suggests tobacco use is plateauing after years of decline. The availability of inexpensive contraband tobacco products maybe contributing to this situation. Limited research has been conducted on the use of contraband tobacco and despite the increasing availability of contraband 'Native cigarettes', no studies to date have examined their use among young adults. Accordingly, this study examines: (a) what proportion of cigarette butts discarded on post-secondary campuses are contraband; and (b) whether the proportion of contraband butts varies between colleges and universities, across seven geographical regions in the province and based on proximity First Nations reserves. In March and April 2009, discarded cigarette butts were collected from the grounds of 25 post-secondary institutions across Ontario. At each school, cigarette butts were collected on a single day from four locations. The collected cigarette butts were reliably sorted into five categories according to their filter tip logos: legal, contraband First NationslNative cigarettes, international and suspected counterfeit cigarettes, unidentifiable and unknown. Contraband use was apparent on all campuses, but varied considerably from school to school. Data suggest that contraband Native cigarettes account for as little as 1% to as much as 38 % of the total cigarette consumption at a particular school. The highest proportion of contraband was found on campuses in the Northern part of the province. -

Seven Stars Menthol 12 Box” “Seven Stars Menthol 8 Box” “Seven Stars Menthol 5 Box” to Be Rolled out Nationwide from Mid-April 2014

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tokyo, March 13, 2014 Deep Aroma and Rich Taste of Ripened Tobacco Leaves “Seven Stars Menthol 12 Box” “Seven Stars Menthol 8 Box” “Seven Stars Menthol 5 Box” To be rolled out nationwide from mid-April 2014 Japan Tobacco Inc. (JT) (TSE: 2914) has announced the nationwide launch of three new products from the Seven Stars line, one of the most prominent brands in Japan, from mid-April 2014. The new products, “Seven Stars Menthol 12 Box”, “Seven Stars Menthol 8 Box” and “Seven Stars Menthol 5 Box”, offer deep aroma and rich taste, achieved by a blend which includes ripened tobacco leaves. Since its launch in 1969, the Seven Stars brand has consistently offered unique value in terms of flavor, aroma and design, and has been favored by many consumers as a result. With 12 products currently in the Seven Stars lineup including ''Seven Stars'' in the No.1 slot for domestic tobacco sales figures, the brand is now one of the most popular in Japan. ★ Three new products featuring a blend which includes rare ripened tobacco leaves, enhancing the menthol taste The Seven Stars brand is known for its robust smoking sensation and deep flavor. The new “Seven Stars Menthol 12 Box”, “Seven Stars Menthol 8 Box” and “Seven Stars Menthol 5 Box” feature a blend which includes ripened tobacco leaves, which are ripened to a more advanced degree and are only available in limited quantities compared with ordinary tobacco leaves. The ripened leaves are characterized by their deep roasted aroma, sharp flavor and rich smoke sensation, adding depth to the product’s flavor and aroma as well as enhancing its menthol taste. -

Smoking Topography and Biomarkers of Exposure Among Japanese Smokers: Associations with Cigarette Emissions Obtained Using Machine Smoking Protocols

Environ Health Prev Med (2013) 18:95–103 DOI 10.1007/s12199-012-0293-7 REGULAR ARTICLE Smoking topography and biomarkers of exposure among Japanese smokers: associations with cigarette emissions obtained using machine smoking protocols Mariko Matsumoto • Yohei Inaba • Ichiro Yamaguchi • Osamu Endo • David Hammond • Shigehisa Uchiyama • Gen Suzuki Received: 21 July 2011 / Accepted: 21 June 2012 / Published online: 19 July 2012 Ó The Japanese Society for Hygiene 2012 Abstract using the ISO protocol were smoked more intensely than Objectives Although the relative risk of lung cancer due brands with lower levels of ventilation. The smokers of to smoking is reported to be lower in Japan than in other ‘‘ultra-low/low’’ nicotine-yield cigarettes smoked 2.7-fold countries, few studies have examined the characteristics of more intensively than those of ‘‘medium/high’’ nicotine- Japanese cigarettes or potential differences in smoking yield cigarette smokers to achieve the same level of sali- patterns among Japanese smokers. vary cotinine (p = 0.024). CO levels in expiratory breath Methods To examine tar, nicotine and carbon monoxide samples were associated with puff volume and self-repor- (TNCO) emissions from ten leading cigarettes in Japan, ted smoking intensity, but not with nominal values of machine smoking tests were conducted using the Interna- nicotine-yield reported on cigarette packages. tional Organization for Standardization (ISO) protocol and Conclusions Japanese smokers engaged in ‘‘compensa- the Health Canada Intense (HCI) protocol. Smoking tory smoking’’ to achieve their desired nicotine intake, and topography and tobacco-related biomarkers were collected levels of exposure were greater than those suggested by the from 101 Japanese smokers to examine measures of nominal value of nicotine and tar yields reported on ciga- exposure. -

Rich Flavor and Aroma“Seven Stars Real Rich”,Deep Flavor and Aroma

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tokyo, October 28, 2013 ~Two products from Seven Stars that offer the ultimate in taste~ Rich flavor and aroma: “Seven Stars Real Rich” Deep flavor and aroma: “Seven Stars Real Smoke” To be launched nationwide in early December 2013 Japan Tobacco Inc. (JT) (TSE: 2914) has announced the nationwide early-December launch of two new products from Seven Stars, one of the most prominent brands in Japan: “Seven Stars Real Rich,” the ultimate in rich flavor and aroma, and “Seven Stars Real Smoke,” the ultimate in deep flavor and aroma. Since its launch in 1969, Seven Stars has consistently offered unique value in terms of flavor, aroma and design, and as a result has become extremely popular among consumers. In fact, with “Seven Stars” in the No. 1 slot for domestic tobacco sales figures1 and 10 products in the lineup, the brand is now one of the most popular in Japan. Two products simultaneously released from Seven Stars, offering the ultimate in richness and depth, respectively Seven Stars is a brand known for its robust smoking sensation and deep flavor. The newly launched “Seven Stars Real Rich” and “Seven Stars Real Smoke” preserve these aspects of Seven Stars and at the same time, using only the most stringently selected leaf tobacco, embody the ultimate in richness and depth, respectively. With “Seven Stars Real Rich,” only select leaf tobacco is used to bring out the quality taste, resulting in a rich and mellow flavor and aroma with no roughness. For the package design, the basic Seven Stars design was used as a template but given a deep red base tone rendered in sophisticated hues, representing the rich aroma and depth of the product.