IRIS 2009-247.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Anleggskonsesjon

Anleggskonsesjon Meddelt: Agder Energi Nett AS Organisasjonsnummer: 982974011 Dato: 15.06.2016 Varighet: 01.01.2046 Ref: 201507222-4 Kommune: Arendal, Åmli (Aust-Agder), Farsund, Flekkefjord, Kristiansand, Lindesnes, Lyngdal, Mandal, Marnardal, Sirdal, Vennesla, Åseral (Vest-Agder), Nissedal (Telemark) Fylke: Aust-Agder, Vest-Agder og Telemark Side 2 I medhold av lov av 29. juni 1990 nr. 50 om produksjon, omforming, overføring, omsetning, fordeling og bruk av energi m.m. (energiloven) § 3-1, jf. forskrift av 7.desember 1990 nr. 959 om produksjon, omforming, overføring, omsetning, fordeling og bruk av energi m.m. (energilovforskriften) § 3-1 og delegering av myndighet fra Olje- og energidepartementet i brev av 27. november 2013, gir Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat under henvisning til søknader av 14.12.2015 og 21.12.2015 anleggskonsesjon til Agder Energi Nett AS Anleggskonsesjonen gir rett til å fortsatt drive følgende elektriske anlegg (Agder Energi Netts egen anleggsreferanse er angitt på anleggene): Transformatorstasjoner: 1. Augland transformatorstasjon, Kristiansand kommune (3551) En transformator med ytelse 25 MVA og omsetning 66 (132) /22 kV 66 kV innendørs koblingsanlegg med ett bryterfelt (driftes på 50 kV) Nødvendig høyspenningsanlegg 2. Barbu transformatorstasjon, Arendal kommune (3526) To transformatorer hver med ytelse 35 MVA og omsetning 132/10 kV 132 kV innendørs koblingsanlegg med ett bryterfelt Nødvendig høyspenningsanlegg 3. Bjelland transformatorstasjon, Marnardal kommune (3583) 132 kV koblingsanlegg med to bryterfelt (driftes på 110 kV) Nødvendig høyspenningsanlegg 4. Elvegata transformatorstasjon, Kristiansand kommune (3555) To transformatorer hver med ytelse 25 MVA og omsetning 50/11 kV 66 kV innendørs koblingsanlegg med fem bryterfelt (driftes på 50 kV) Nødvendig høyspenningsanlegg 5. -

Laudalstevne 2009, Laudal SKL, 05-06.06.2009: Mesterskap: Klasse 3-5: 1

Laudalstevne 2009, Laudal SKL, 05-06.06.2009: Mesterskap: Klasse 3-5: 1. May Elin Stava, Lyngdal (5) 344, 2. Trygve Carlsen Kjørslevik, Farsund (4) 342, 3. Steinar Skoland, Lyngdal (5) 342, 4. Oddvar Kvåle, Holum (5) 342, 5. Kenneth Stubstad, Mandal (5) 342 Klasse 1: 1. Geir Sjøveian, Flikka 240, 2. Svein Storebaug, Laudal 237 Klasse 2: 1. Sven Helge Langeland, Øvrebø 226, 2. Audun Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 199 V55: 1. Harald Jensen, Lyngdal 344, 2. Øyvind Lilledrange, Flikka 344, 3. Asbjørn Dale, Heddeland og Breland 339 Rekrutt: 1. Iselin Sådland Jensen, Lyngdal 344, 2. Johanna Spilde, Lyngdal 344, 3. Inga Lill Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 337 Eldre rekrutt: 1. Ole Nicolai Jåtun, Greipstad 349, 2. Håkon Sørli, Greipstad 349, 3. Martin Landås, Øvrebø 345 Junior: 1. Aleksander Taanevig, Farsund 348, 2. Vegard Blien Sjøveian, Flikka 347, 3. Kristoffer Birkeland, Øvre Eiken 345 V65: 1. Tolleif Netland, Kvinesdal 348, 2. Rolf Gabrielsen, Farsund 348, 3. Georg Homme, Øvrebø 344 V73: 1. Torjus Ågedal, Grindølen 349, 2. Aslak Wigemyr, Heddeland og Breland 242 Hovedskyting: Klasse 1: 1. Geir Sjøveian, Flikka 240, 2. Svein Storebaug, Laudal 237 Klasse 2: 1. Sven Helge Langeland, Øvrebø 226, 2. Audun Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 199 Klasse 3: 1. Torgeri Jåtun, Greipstad 234, 2. Fred Erik Berge, Laudal 232, 3. Øyvind Orthe, Øvre Eiken 231, 4. Kjell Salve Moi, Evje og Hornnes 227, 5. Bjørn Mølland, Greipstad 226, 6. Per A Pedersen, Kristiansand 226, 7. Anders Hommen, Greipstad 224, 8. Dagfinn Vemmelvik, Greipstad 213, 9. Øystein Solås, Heddeland og Breland 210, 10. Kjell Torsvik, Kristiansand 205, 11. -

Folketeljing 1900 for 0936 Hornnes Digitalarkivet

Folketeljing 1900 for 0936 Hornnes Digitalarkivet 25.09.2014 Utskrift frå Digitalarkivet, Arkivverket si teneste for publisering av kjelder på internett: http://digitalarkivet.no Digitalarkivet - Arkivverket Innhald Løpande liste .................................. 9 Førenamnsregister ........................ 51 Etternamnsregister ........................ 63 Fødestadregister ............................ 75 Bustadregister ............................... 87 4 Folketeljingar i Noreg Det er halde folketeljingar i Noreg i 1769, 1801, 1815, 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1870 (i nokre byar), 1875, 1885 (i byane), 1891, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1946, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 og 2001. Av teljingane før 1865 er berre ho frå 1801 nominativ, dvs. ho listar enkeltpersonar ved namn. Teljingane i 1769 og 1815-55 er numeriske, men med namnelistar i grunnlagsmateriale for nokre prestegjeld. Statistikklova i 1907 la sterke restriksjonar på bruken av nyare teljingar. Etter lov om offisiell statistikk og Statistisk Sentralbyrå (statistikklova) frå 1989 skal desse teljingane ikkje frigjevast før etter 100 år. 1910-teljinga blei difor frigjeven 1. desember 2010. Folketeljingane er avleverte til Arkivverket. Riksarkivet har originalane frå teljingane i 1769, 1801, 1815-1865, 1870, 1891, 1910, 1930, 1950, 1970 og 1980, mens statsarkiva har originalane til teljingane i 1875, 1885, 1900, 1920, 1946 og 1960 for sine distrikt. Folketeljinga 3. desember 1900 Ved kgl. res. 8. august 1900 blei det bestemt å halde ei "almindelig Folketælling" som skulle gje ei detaljert oversikt over befolkninga i Noreg natta mellom 2. og 3. desember 1900. På kvar bustad skulle alle personar til stades førast i teljingslista, med særskild markering ("mt") av dei som var mellombels til stades (på besøk osb.) på teljingstidspunktet. I tillegg skulle alle faste bebuarar som var fråverande (på reise, til sjøs osb.) frå bustaden på teljingstidspunktet, også førast i lista, men merkast som fråverande ("f"). -

Visitasforedrag Bjelland, Laudal, Oyslebo Og

1 DEN NORSKE KIRKE Agder og Telemark biskop VISITASFOREDRAG BJELLAND-, LAUDAL-, ØYSLEBØ- OG ÅSERAL SOKN 7.-12. MAI 2014. INNLEDNING Kjære menigheter i Bjelland-, Laudal-, Øyslebø- og Åseral sokn. Nåde være med dere, og fred fra Gud vår Far og Herren Jesus Kristus Jeg starter med å takke. Det er jo ikke lenge siden jeg var på besøk hos dere som prost. Derfor var dere ikke ukjente for meg da vi startet forberedelsene til visitasen. Men visitas er likevel noe annet. Den gir et dypere og bredere kjennskap til menighet og samfunn. Takk for at dere har lukket meg inn i deres utfordringer og muligheter. Takk for at dere ærlig har delt med meg gleder og vanskeligheter. Forrige visitas var i Åseral i 2004 og i Bjelland, Laudal og Øyslebø i 2003. Siden den gang har kirken fått nytt visitasreglement som blant annet slår visitasenhetene sammen til større enheter, og som sier at biskopen mer skal høre de lokalt ansatte enn å preke selv. Jeg ser at det er forskjell mellom de forskjellige soknene, men også mye likt. Overalt har jeg møtt menigheter som tro mot kallet fra Gud og med kjærlighet til menneskene rundt seg, bygger menighet. Min bønn er at visitasen blir til inspirasjon i deres videre arbeid. FORBEREDELSE En visitas er ikke bare det som skjer disse dagene. I forkant skriver sokneprest sammen med råd og kirkeverge en visitasmelding. En slik melding er en beskrivelse og en vurdering av det som har skjedd siden forrige visitas og av situasjonen i dag. Jeg oppfordrer menigheten til å lese disse meldingene. -

Om Kirkesagn Og Ødekirker Muntlig Tradisjon Og Stedsnavn Som Kilder for Kirkeforskningen

Om kirkesagn og ødekirker Muntlig tradisjon og stedsnavn som kilder for kirkeforskningen Av Jan Brendalsmo og Frans-Arne Stylegar 1. Ødekirker og kirkesagn til gården B, som i dag er kirkested. I et par tilfeller »Thessa jorder lago till Selnes kirkia j Hempne som blir den endelige lokaliteten bestemt ved at man no er nider fallen«. Dette er overskriften for en liten bandt en stokk til en unghest, og der den stoppet ble innførsel i erkebiskop Aslak Bolts jordebok fra 1430- kirken bygd. Det finnes også eksempler der en storm tallet, hvor det listes opp en rekke gårder og gård- drev tømmeret til en gitt lokalitet og således avgjor- parter som lå til St. Olav, dvs. domkirkens mensa.1 de kirkens plassering. Denne siste varianten er rim- Var det ikke for denne innførselen kunne vi ikke ligvis knyttet til kirker ved sjøen. Innenfor gruppe to, være sikre – i Weibulliansk mening – på at det en- kirker med flyttingssagn, finnes det interessant nok gang hadde stått kirke på gården Selnes i Sør-Trøn- 12 eksempler hvor det gjennom skriftlige og/eller delag. Det finnes ikke andre skriftlige kilder hvor arkeologiske kilder kan belegges at det faktisk har denne kirken er nevnt, ei heller er det funnet skje- stått kirke på det stedet som i sagnet blir utpekt som letter eller kister ved grøfting eller annet gårdsar- opprinnelig byggeplass. (fig. 2 viser et eksempel, beid på stedet. Det finnes kun en tradisjon på går- bygda Ørlandet i Sør-Trøndelag med åtte kirker i den om at det skal ha stått kirke der, samt lokalitets- middelalderen, to av dem med flyttingssagn).3 navnene Kjerkevollen og Presthusvika. -

Mandalsvassdraget

Mandalsvassdraget Koordinator: Ø. Kaste, NIVA 1 Innledning 1.3 Forbruk av avsyringsmiddel i 2005 Følgende data er mottatt fra Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder 1.1 Områdebeskrivelse v/miljøvernavdelingen: Hovedelva: Doserer v/Bjelland: 812 tonn Vassdragsnr: 022 Doserer v/Håverstad 2575 tonn Fylke(r): Aust- og Vest-Agder Doserer v/Smeland 1024 tonn Areal, nedbørfelt: 1809 km2 Sidevassdrag: Doserer v/Egså 106 tonn Regulering: Omfattende reguleringer og interne Doserer v/Bjørndalen 883 tonn overføringer, spesielt i øvre del. Doserer Hesså 42 tonn Spesifikk avrenning: 47,6 l/s/km2 Doserer Logåna 54 tonn Middelvannføring: 85,5 m3/s Doserer Høyeåna (Brandsvoll) 69 tonn Kalket siden: Fullkalket fom. juni 1997 Doserer Høyeåna (v. utløp) 174 tonn Lakseførende strekning: 48 km, til Kavfossen oppstrøms Bjelland (Figur 1.1) SUM: 5739 tonn Type avsyringsmiddel: 1.2 Avsyringsstrategi Logåna: Silikatlut (SiO2) Øvrige doserere: NK3 Kalksteinsmel (86% CaCO3) Bakgrunn for tiltak: Laksebestanden i elva, som tidligere var en av landets beste, er i dag I tillegg ble det spredd 112 tonn kalksteinsmel (SK3) i 13 utdødd pga. forsuring. Sjøauren har innsjøer i nedbørfeltet i 2005. så langt overlevd, men tettheten av ungfisk er lav og mye av repro- duksjonen skjer i sidebekkene (Larsen og Haraldstad 1994). Tiltakssplan: Larsen og Haraldstad (1994). Biologisk mål: Å sikre tilstrekkelig god vannkvalitet for reproduksjon av laks i elva. Dette vil samtidig sikre livsmiljøet for de fleste andre forsuringsfølsomme vannorganismer. Vannkvalitetsmål: Lakseførende strekning: 15/2-31/5: pH 6,2, 1/6-14/2: pH 6,0. Avsyringssstrategi: Vassdraget avsyres ved hjelp av tre store doserere plassert i hovedelva og 6 mindre doserere plassert i sure sidevassdrag. -

Dendrokronologisk Undersøgelse Af Borekerner Fra Laudal Kirke I Norge

Dendrokronologisk undersøgelse af borekerner fra Laudal kirke, Marnadal kommune, Vest-Agder Fylke, Norge NNU Rapport 65 - 2016 Hanne Marie Larsen AD 1382 1400 1450 1500 1550 1600 1650 1700 1750 1800 1822 Eg 10 N3380029 1 10 N3380059 1 Fyr 10 N3380019 1 10 N3380049 1 Dendrokronologisk Laboratorium Miljøarkæologi og Materialeforskning Bevaring og Naturvidenskab Nationalmuseet NNU Rapport 65 - 2016 Dendrokronologisk undersøgelse af borekerner fra Laudal kirke i Norge Dendrokronologisk objekt: Borekerner fra hus Fylke: Vest-Agder Kommune nr.: Marnadal Gnr./Bnr.: 43/44 Koordinater: 58.24701668 / 7.504475 Dendrokronologisk undersøgelse Træart: Quercus sp. (eg) og Pinus sylvestris (fyr) Formål: Datering og grundkurveopbygning Indsender: Fylkeskonservatoren i Vest-Agder Fylke og Vest-Agder Museum Prøvetagning: Niels Bonde og Christoffer Christensen Undersøgt af Hanne Marie Larsen NNU j.nr. A9430, oktober 2016 Publicering: Med mindre andet er aftalt, kan resultatet frit anvendes med henvisning til denne rapport. Kontakt evt. laboratoriet for hjælp og yderligere oplysninger ([email protected]). Rapporten kan downloades fra hjemmesiden www.nnu.dk under Dendrokronologi, Rapporter. Datering af borekerner fra Laudal kirke Den dendrokronologiske undersøgelse er foretaget på baggrund af 5 borekerner, hvoraf 3 borekerner kommer fra eg (Quercus sp.) og 2 borekerner fra fyr (Pinus sylvestris). Alle borekerner er udtaget fra Laudal kirke i Marnadal i Norge. Prøve 3 består af to delprøver, som er benævnt henholdsvis N3380038 og N3380039. Ingen af prøverne indeholder marv. Splinten er bevaret på N3380038 (eg), mens splint og muligvis også bark er bevaret på N3380019 (fyr). Antallet af årring spænder over 16 til 205 år. På baggrund af grundkurver fra Norge og intern krydsdatering er 4 ud af 5 prøver dateret. -

Curriculum Vitae Einar Leknes

CV Einar Leknes March 2020 NORCE, Departement of Social Sciences Curriculum vitae Einar Leknes *ROLE IN THE PROJECT Project manager ☐ Project partner ☐ *PERSONAL INFORMATION *Family name, First name: Leknes, Einar *Date of birth: 22.11.1956 *Sex: Male *Nationality: Norwegian *EDUCATION PhD: Disputation date: 10.11.1999. Thesis: Management by objectives, rule compliance and negotiations Decision-theoretical perspectives on the public handling of the interests of the fisheries, the environment and regional authorities connected to the approval of plans for development and operation of petroleum fields and pipelines during the period 1985 – 1997. Institute for Urban and Regional Planning/ Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway 1975-1981 Master: Civil Engineer Institute for Urban and Regional Planning/ Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway *CURRENT AND PREVIOUS POSITIONS 2018 Research Leader; Research Group: Climate, Environment, Sustainability NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, Department of Social Sciences 2013-2018 Senior Vice President, Department of Social Sciences International Research Institute of Stavanger (IRIS): 2006-2013 Research Director, Several research groups, Department of Social Sciences International Research Institute of Stavanger (IRIS) 2000-2005 Head of Research, Department of Social Sciences RF Rogaland Research: 1997-2000 Staff Engineer, HSE, Environmental Impact Assessment, Statoil ASA 1990-1997 Senior Research Scientist, Department of Social Sciences RF Rogaland Research 1986-1990 Consultant, -

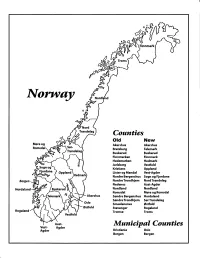

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Validation of a Swimming Direction Model for the Downstream Migration of Atlantic Salmon Smolts

water Article Validation of a Swimming Direction Model for the Downstream Migration of Atlantic Salmon Smolts Marcell Szabo-Meszaros 1,*,† , Ana T. Silva 2,† , Kim M. Bærum 3, Henrik Baktoft 4, Knut Alfredsen 1 , Richard D. Hedger 2, Finn Økland 2, Karl Ø. Gjelland 5, Hans-Petter Fjeldstad 6,‡, Olle Calles 7 and Torbjørn Forseth 2 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, S. P. Andersens 5, 7491 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Høgskoleringen 9, 7043 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] (A.T.S.); [email protected] (R.D.H.); fi[email protected] (F.Ø.); [email protected] (T.F.) 3 Norwegian Institute of Nature Research (NINA), Fakkelgården, 2624 Lillehammer, Norway; [email protected] 4 National Institute of Aquatic Resources, Technical University of Denmark, 8600 Silkeborg, Denmark; [email protected] 5 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Hjalmar Johansens gate 14, 9007 Tromsø, Norway; [email protected] 6 SINTEF Energy Research, Sem Sælandsvei 11, 7048 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] 7 River Ecology and Management Research Group RivEM, Department of Environmental and Life Sciences, Karlstad University, 651 88 Karlstad, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Contributed equally to this work and are considered to be co-first authors. Citation: Szabo-Meszaros, M.; Silva, ‡ Deceased in March 2020. A.T.; Bærum, K.M.; Baktoft, H.; Alfredsen, K.; Hedger, R.D.; Økland, Abstract: Fish swimming performance is strongly influenced by flow hydrodynamics, but little is F.; Gjelland, K.Ø.; Fjeldstad, H.-P.; known about the relation between fine-scale fish movements and hydrodynamics based on in-situ Calles, O.; et al.