Broken Music, Or the Wondrous Story of How a Fine Voice Was Delivered from the Treacherous Clutches of Deception and Returned to Itself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip. -

Infomail 1456: Dvds Von PAUL Mccartney

Alter Markt 12 • 06 108 Halle (Saale) • Telefon 03 45 - 290 390 0 : Di., Mi., Do., Fr., Sa., So. und an Feiertagen jeweils von 10 bis 20 Uhr InfoMail 1456: DVDs von PAUL McCARTNEY Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan, wir haben folgende DVDs mit PAUL McCARTNEY: 3er DVD THE McCARTNEY YEARS. DVD 1: 1. Tug Of War; 2. Say Say Say; 3. Silly Love Songs; 4. Band On The Run; 5. Maybe I'm Amazed; 6. Heart Of The Country; 7. Mamunia; 8. With A Little Luck; 9. Goodnight Tonight; 10. Waterfalls; 11. My Love; 12. C Moon; 13. Baby's Request; 14. Hi Hi Hi; 15. Ebony And Ivory; 16. Take It Away; 17. Mull Of Kintyre; 18. Helen Wheels; 19. I've Had Enough; 20. Coming Up; 21. Wonderful Christmastime. Extra 1: Juniors Farm. Extra 2: Band On The Run. Extra 3: London Town. Extra 4: Oktober 1977: aus Fernsehsendung THE SOUTH BANK SHOW, Großbritannien: Mull Of Kintyre #2. DVD 2: 1. Pipes Of Peace; 2. My Brave Face; 3. Beautiful Night; 4. Fine Line; 5. No More Lonely Nights; 6. This One; 7. Little Willow; 8. Pretty Little Head; 9. Birthday; 10. Hope Of Deliverance; 11. Once Upon A Long Ago; 12. All My Trials; 13. Brown-Eyed Handsome Man; 14. Press; 15. No Other Baby; 16. Off The Ground; 17. Biker Like An Icon; 18. Spies Like Us; 19. Put It There; 20. Figure Of Eight; 21. C'Mon People. Extras: 1. PARKINSON; 2. So Bad. Extra 3: Donnerstag, 28. Juni 2005: CHAOS AND CREATION AT ABBEY ROAD. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

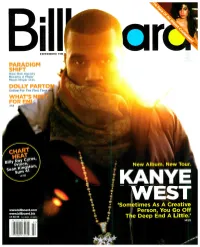

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Titre Construit 1Er Responsable Série Edith Piaf

Titre construit 1er responsable Série Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (20) : Volume 20 : Carnegie Hall 1956-1957 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (19) : Volume 19 : Carnegie Hall 1956 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (18) : Volume 18 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (17) : Volume 17 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] Léo chante Ferré (16) : Léo chante l'espoir Ferré, Léo (1916 - 1993) Léo chante Ferré / Léo Ferré [Universal Music S.A.] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (16) : Volume 16 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] Intégrale 1965-1995 (16) : Disque 16 Sardou, Michel Intégrale 1965-1995 / Michel Sardou [Universal Music France S.a] Léo chante Ferré (15) : Léo chante Et ... basta ! Ferré, Léo (1916 - 1993) Léo chante Ferré / Léo Ferré [Universal Music S.A.] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) (15) : Volume 15 Piaf, Edith Edith Piaf (1963-2003) / Edith Piaf [Emi Music] L'Intégrale (15) : Les Marquises Brel, Jacques L'Intégrale / Jacques Brel [Universal Music France S.a] Intégrale 1965-1995 (15) : Disque 15 Sardou, Michel Intégrale 1965-1995 / Michel Sardou [Universal Music France S.a] L'Intégrale studio de Claude Nougaro (14) : Embarquement immédiat Nougaro, Claude L'Intégrale studio de Claude Nougaro / Claude Nougaro [Mercury France] Intégrale 1965-1995 (14) : Disque 14 Sardou, Michel Intégrale 1965-1995 / Michel Sardou [Universal Music France S.a] Edith Piaf (1963-2003) -

Artist Review: Revisiting Sting-An Under-Recognized Existentialist Song Writer1

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation ISSN: 2582-7138 Received: 01-05-2021; Accepted: 18-05-2021 www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May-June 2021; Page No. 550-561 Artist review: Revisiting sting-an under-recognized Existentialist song writer1 Li Jia International College, Krirk University, Thanon Ram Intra, Khwaeng Anusawari, Khet Bang Khen, Krung Thep, Maha Nakhon10220, Thailand Corresponding Author: Li Jia Abstract Artistic expressions such as songs and poetry are examples of a solo artist but also helped him in communicating his free activities and are privileged modes of revealing what the thoughts and ideals to the world. His music, words and life world is about. Art’s power, in the case of existentialism, is are inextricably linked and this can be seen in many of Sting to a large extent devoted to expressing the absurdity of the ’s confessional songs that have connections to events in his human condition since for the existentialists, the world in no personal life. Existential characteristics have affected Sting longer open to the human desire of meaning and order. Sting both as a person and a musician. This paper calls for more is included in this pool of gifted artist and his talent in making researches on his music legacy that the world owned him for songs has not only paved the way for his successful career as a long time. Keywords: Sting, Existentialist, Song Writer Introduction Artistic expressions such as songs and poetry are examples of free activities and are privileged modes of revealing what the world is about. -

Paul Mccartney / Wings

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 1 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Paul McCartney / Wings No. of Titles Positions Sir James Paul McCartney CH MBE (born 18 Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 June 1942) is an English singer-songwriter, 1 39 6 2 420 55 15 multi-instrumentalist, and composer. He gained 1 60 24 3 499 107 14 worldwide fame as the bass guitarist and 1 48 23 9 559 154 30 singer for the rock band the Beatles, widely considered the most popular and influential 1 73 31 11 1.478 316 59 group in the history of popular music. His songwriting partnership with John Lennon remains the most successful in history. After the group disbanded in 1970, he pursued a solo career and formed the band ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Another Day 03/1971 6 13 1602/1971 2 12 03/1971 5 12 5 2 Uncle Albert / Admiral Halsey 11/1971 30 4 08/1971 1 1 13 7 ► Paul & Linda McCartney 3 Eat At Home 08/1971 28 8 ► Paul & Linda McCartney 4 Back Seat Of My Car 08/1971 39 5 ► Paul & Linda McCartney 5 Give Ireland Back To The Irish 02/1972 16 8 03/1972 21 8 ► Wings 6 Mary Had A Little Lamb 05/1972 9 11 3 06/1972 28 7 ► Wings 7 Hi, Hi, Hi 01/1973 16 17 12/1972 5 13 4112/1972 10 11 ► Wings 8 My Love 06/1973 43 1 04/1973 9 11 2904/1973 1 4 18 ► Paul McCartney & Wings 9 Live And Let Die 07/1973 31 6 06/1973 9 14 1707/1973 2 14 ► Paul McCartney & Wings 10 Helen Wheels 12/1973 33 3 11/1973 12 12 11/1973 10 13 1 ► Paul McCartney & Wings 11 -

The 40 Biggest Hits by the Beatles--Together and Apart"

,,, ....... * * ,11tfeRiC'!l.a... ~"TOP._. •• PRESS AND ADVERTISING MATERIALS 10 for A Special & Exclusive Countdown "THE 40 BIGGEST HITS OF JOHN, PAUL, GEORGE, AND RINGO - AS THE BEATLES, AND ON THEIR OWN." July 4th Weekend As you know, Casey Kasem has been promoting a Special Countdown of the greatest hits of the Beatles - together and apart - for several weeks on AMERICAN TOP 40. The Special Countdown rolls around the weekend of July 4th. In order to promote the Special on a local level, we are supplying you with a sheet of repro paper on which are printed the graphics for you to use in newspaper ads. Print ads for the Special Countdown should be built from these elements. The boxed announcement of the Snecial is designed as a two-column newspaper ad. However, it may be "blown up" to suit your needs. We have provided you with an AMERICAN TOP 40 logo and Casey Kasem's name in case you want to take a crack at designing a Special announcement yourself. Your own art department or the layout person at the publication will know what to do when you present these raw materials. You, of course, will be required to add such pertinent information as your call letters, your own logo, dial position and dates and times. A Sample Press Release "The 40 Biggest Hits of John, Paul, George, and Ringo ... as the Beatles, and On Their Own" will be featured in a special edition of the weekly radio program "American Top 40." The four-hour tribute to the musical genius of the Beatles is hosted by Casey Kasem and can be heard on station (calls) on (day and/or date) at (time). -

Beatles History – Part Three: 1970-2008

BEATLES HISTORY – PART THREE: 1970-2008 The Solo Careers In September 1969, John Lennon told his musical partners at a business meeting that he was leaving The Beatles. It was decided that the split was to be kept secret until the group had secured a profitable new contract with EMI Records. In early 1970, The Beatles’ staff prepared the release of Let It Be, which had been recorded in January 1969. As George Martin had lost interest in the production, American producer Phil Spector was asked to turn The Beatles’ rough recordings into a valuable album. Spec- tor’s involvement, however, caused further friction between the band members, because Paul McCartney felt that Spector was ruining his song “The Long and Winding Road” with a lavish arrangement featuring an orchestra and a choir. In addition, the release of Let It Be collided with the release date of Paul McCartney’s first solo album, McCartney, which was scheduled for 10 April, 1970. The conflicts within the band finally reached their climax when the other Beatles ignored McCartney’s wish of removing Spector’s orchestral arrangement from the recording of his song. Consequently, Paul McCartney decided to inform the public that The Beatles had disbanded. The promotional copies of McCartney’s first album contained an interview, in which he stated that he did not want to work with The Beatles anymore, because of personal and musical dis- agreements. The release date of McCartney is therefore regarded as the date The Beatles broke up, although they legally existed as a band until 1976, when their contracts finally expired. -

Download the Archives Here

23.12.12 Merry Christmas Here comes the time for a family gathering. Hope your christmas tree will have ton of intersting presents for you. 22.12.12 Sting to perform in Jodhpur in march Sting is sheduled to perform in march (8, 9 or 10) for Jodhpur One World Retreat. It will be a private show for head injury victims. Only 250 couples will attend the party, with 30,000$ to 60,000$ donations. More information on jodhpuroneworld.org. 22.12.12 The last ship I made some updates to the "what we know about the play" on the forum. Please, check them to know all the informations about "The Last Ship", that could be released in 2013-2014. 16.12.12 Back to bass tour : the end The Back to bass tour has ended yesterday (well, that's what some fans hope) in Jakarta. You'll find all the tour history on the forum, and all informations about the "25 years" best of, that pointed the start of this world tour on this special page. What will follow ? We know that Sting's musical "The last ship" could be released in 2013/2014. We also know that he will perform in France and Marocco this summer. 10.12.12 Back to Bass last dates reports Follow the recent reports from the past shows from Back to Bass tour in Eastern Europe and Asia. Sting and his band met warm audiences (yesterday one in Manilla seems to have been the best from the tour according to Peter and Dominic's tweets and according to various Youtube crazy videos) You'll find pictures and videos on the forum. -

Sting I Ll Be Watching You

1 / 2 Sting I Ll Be Watching You Letra da música I'll Be Watching You - Sting. Aprenda a tocar no Cifra Club - seu site de cifras, tablaturas e videoaulas.. Every breath you take. And every move you make. Every bond you break, every step you take. I'll be watching you. Every single day. And every .... Sting - Live 1991 Verona - Muoio per te - Every breath you take - with Zucchero We had a ... Every breath you take and every cake you bake I"ll be watching you.. “We had talks at different times about 'Hey Steve, would you be ... Warrior's doing our gimmick up there, I'll do it down there and there was a .... You know, I don't think I've ever seen him do a malicious thing. ... I guess watching TV is hisfavorite pastime, he'll watch anything, butdon't sitthere watching it .... Every breath you take Every move you make Every bond you break Every step you take I'll be watching you Každý nádech, který učiníš Každý pohyb, který uděláš .... ... Every Breath You Take, I'll Be Watching You”- Grandma and Sting ... She doesn't have to hide in your cell phone like a coward to tell you .... Every breath you take. And every move you make. Every bond you break. Every step you take. Ill be watching you. Every single day. And every word you say. Every breath you take I'll be watching you. Every breath you take I'll be watching you Sting. add your own caption. 363 shares. like; meh.