Some Brief Reflections Philip Schlesinger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-Petition Session: TV Licensing, HC 1233

Petitions Committee Oral evidence: E-petition session: TV Licensing, HC 1233 Monday 1 March 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 March 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Catherine McKinnell (Chair); Tonia Antoniazzi; Jonathan Gullis. Other Members present: Rosie Cooper; Damian Collins; Gill Furniss; Gareth Bacon; Jamie Stone; Ben Bradley; Tahir Ali; Brendan Clarke-Smith; Allan Dorans; Virginia Crosbie; Mr Gregory Campbell; Simon Jupp; Jeff Smith; Huw Merriman; Chris Bryant; Mark Eastwood; Ian Paisley; John Nicolson; Chris Matheson; Rt Hon Mr John Whittingdale OBE, Minister for Media and Data. Questions 1-21 Chair: Thank you all for joining us today. Today’s e-petition session has been scheduled to give Members from across the House an opportunity to discuss TV licensing. Sessions like this would normally take place in Westminster Hall, but due to the suspension of sittings, we have started holding these sessions as an alternative way to consider the issues raised by petitions and present these to Government. We have received more requests to take part than could be accommodated in the 90 minutes that we are able to schedule today. Even with a short speech limit for Back- Bench contributions, it shows just how important this issue is to Members right across the House. I am pleased to be holding this session virtually, and it means that Members who are shielding or self-isolating, and who are unable to take part in Westminster Hall debates, are able to participate. I am also pleased that we have Front-Bench speakers and that we have the Minister attending to respond to the debate today. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

Press Standards, Privacy and Libel: Press Complaints Commission's

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Press standards, privacy and libel: Press Complaints Commission’s Response to the Committee’s Second Report of Session 2009–10 1st Special Report of Session 2009–10 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 29 March 2010 HC 532 Published on 6 April 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon and East Chelmsford) (Chair) Mr Peter Ainsworth MP (Conservative, East Surrey) Janet Anderson MP (Labour, Rossendale and Darwen) Mr Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr Mike Hall MP (Labour, Weaver Vale) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Adam Price MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/cmscom. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2015 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Prime Minister 3 Attorney General’s Office 5 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 6 Cabinet Office 8 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 12 Ministry of Defence 14 Department for Education 16 Department of Energy and Climate Change 18 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 19 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 20 Department of Health 22 Home Office 24 Department for International Development 26 Ministry of Justice 27 Northern Ireland Office 30 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 31 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 32 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 33 Scotland Office 34 Department for Transport 35 HM Treasury 37 Wales Office 39 Department for Work and Pensions 40 Government Whips – Commons 42 Government Whips – Lords 46 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list in writing of all relevant interests known to them which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate. -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON-MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2-3 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4-7 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8-70 Part IV Executive Agencies 71-82 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 83-90 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 91 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 92-93 Part VIII Index 94-96 Information contained in this document can also be found on Ministers’ pages on GOV.UK and: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister; First Lord of the Treasury; Minister for the Civil Service and Minister for the Union The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs; First Secretary of State The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Minister for the Cabinet Office; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP COP26 President Designate The Rt Hon -

Press Coverage of the Debate That Followed the News of the World Phone Hacking Scandal : the Use of Sources in Journalistic Metadiscourse

This is a repository copy of Press coverage of the debate that followed the News of the World phone hacking scandal : the use of sources in journalistic metadiscourse. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/165722/ Version: Published Version Article: Ogbebor, B. orcid.org/0000-0001-5117-9547 (2018) Press coverage of the debate that followed the News of the World phone hacking scandal : the use of sources in journalistic metadiscourse. JOMEC Journal (12). pp. 145-165. ISSN 2049-2340 10.18573/jomec.173 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ JOMEC Journal Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Published by Cardiff University Press Binakuromo Ogbebor Cardiff University, School of Journalism, Media and Culture Email: [email protected] Keywords Journalistic metadiscourse Media and democracy Media representation News of the World Public sphere Abstract This article examines the distribution of sources in journalistic metadiscourse (news coverage of journalism) and the implication of the manner of distribution for democracy. -

Urgent Open Letter to Jesse Norman Mp on the Loan Charge

URGENT OPEN LETTER TO JESSE NORMAN MP ON THE LOAN CHARGE Dear Minister, We are writing an urgent letter to you in your new position as the Financial Secretary to the Treasury. On the 11th April at the conclusion of the Loan Charge Debate the House voted in favour of the motion. The Will of the House is clearly for an immediate suspension of the Loan Charge and an independent review of this legislation. Many Conservative MPs have criticised the Loan Charge as well as MPs from other parties. As you will be aware, there have been suicides of people affected by the Loan Charge. With the huge anxiety thousands of people are facing, we believe that a pause and a review is vital and the right and responsible thing to do. You must take notice of the huge weight of concern amongst MPs, including many in your own party. It was clear in the debate on the 4th and the 11th April, that the Loan Charge in its current form is not supported by a majority of MPs. We urge you, as the Rt Hon Cheryl Gillan MP said, to listen to and act upon the Will of the House. It is clear from their debate on 29th April that the House of Lords takes the same view. We urge you to announce a 6-month delay today to give peace of mind to thousands of people and their families and to allow for a proper review. Ross Thomson MP John Woodcock MP Rt Hon Sir Edward Davey MP Jonathan Edwards MP Ruth Cadbury MP Tulip Siddiq MP Baroness Kramer Nigel Evans MP Richard Harrington MP Rt Hon Sir Vince Cable MP Philip Davies MP Lady Sylvia Hermon MP Catherine West MP Rt Hon Dame Caroline -

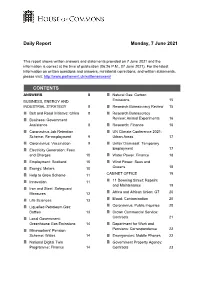

Daily Report Monday, 7 June 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 7 June 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 7 June 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:26 P.M., 07 June 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Natural Gas: Carbon BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Emissions 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Research Bureaucracy Review 15 Belt and Road Initiative: China 8 Research Bureaucracy Business: Government Review: Animal Experiments 16 Assistance 8 Research: Finance 16 Coronavirus Job Retention UN Climate Conference 2021: Scheme: Re-employment 9 Urban Areas 17 Coronavirus: Vaccination 9 Unfair Dismissal: Temporary Electricity Generation: Fees Employment 17 and Charges 10 Water Power: Finance 18 Employment: Scotland 10 Wind Power: Seas and Energy: Meters 10 Oceans 18 Help to Grow Scheme 11 CABINET OFFICE 19 Innovation 11 11 Downing Street: Repairs and Maintenance 19 Iron and Steel: Safeguard Measures 12 Africa and African Union: G7 20 Life Sciences 13 Blood: Contamination 20 Liquefied Petroleum Gas: Coronavirus: Public Inquiries 20 Bottles 13 Crown Commercial Service: Local Government: Contracts 21 Greenhouse Gas Emissions 14 Department for Work and Mineworkers' Pension Pensions: Correspondence 22 Scheme: Wales 14 Emergencies: Mobile Phones 22 National Digital Twin Government Property Agency: Programme: Finance 14 Contracts 23 2 Monday, 7 June 2021 Daily Report Press Conferences: Sign Richard -

Cabinet Committees

Cabinet Committees Constitutional Reform Committee Membership Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (Chair) (The Rt Hon Oliver Letwin MP) First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Rt Hon George Osborne MP) Secretary of State for the Home Department (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP) Leader of the House of Commons, Lord President of the Council (The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP) Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (The Rt Hon Theresa Villiers MP) Secretary of State for Wales (The Rt Hon Stephen Crabb MP) Secretary of State for Scotland (The Rt Hon David Mundell MP) Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government (The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP) Leader of the House of Lords, Lord Privy Seal (The Rt Hon Baroness Stowell MBE) Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury and Chief Whip (The Rt Hon Mark Harper MP) Attorney General (The Rt Hon Jeremy Wright MP) Terms of Reference To consider matters relating to constitutional reform within the United Kingdom. 1 Economic Affairs Committee Membership First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer (Chair) (The Rt Hon George Osborne MP) Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP) Secretary of State for the Home Department (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice (The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP) Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills (The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Iain -

Cabinet Committees

Cabinet Committees Constitutional Reform Committee Membership Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (Chair) (The Rt Hon Oliver Letwin MP) First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Rt Hon George Osborne MP) Secretary of State for the Home Department (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP) Leader of the House of Commons, Lord President of the Council (The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP) Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (The Rt Hon Theresa Villiers MP) Secretary of State for Wales (The Rt Hon Stephen Crabb MP) Secretary of State for Scotland (The Rt Hon David Mundell MP) Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government (The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP) Leader of the House of Lords, Lord Privy Seal (The Rt Hon Baroness Stowell MBE) Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury and Chief Whip (The Rt Hon Mark Harper MP) Attorney General (The Rt Hon Jeremy Wright MP) Terms of Reference To consider matters relating to constitutional reform within the United Kingdom. 1 Economic Affairs Committee Membership First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer (Chair) (The Rt Hon George Osborne MP) Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP) Secretary of State for the Home Department (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice (The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP) Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills (The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Iain -

February 2019

February 2019 This is the ninth update shedding light on what catches the eye in and around Westminster and its satellite community of advisers, think tanks and hangers on. Some of this may have been captured in the headlines and other stuff. Views my own but an acknowledgement that everyone is working hard in a challenging political environment and bad- tempered world….and one last thing, with literally weeks to go to the designated EU leaving date, this edition can’t possibly be a Brexit-free zone. Lisa Hayley-Jones Director, Political and Business Relations BVCA Key Political Dates Theresa May has overtaken Spencer Perceval (the only British Prime Minister in history to be assassinated) to become the 36th longest-serving Prime Minister. Theresa May needs to reach 28th May to surpass Gordon Brown’s record and the following day to outlast the Duke of Wellington. This week was meant to be a Westminster recess, a chance for MPs to take a breather before the final countdown to Brexit Day on 29 March. The failure of the Prime Minister to reach a deal on Brexit that is acceptable to MPs forced the government to cancel their scheduled February break. Instead, activity in the House of Commons has been dominated by Statutory Instruments (SIs). These give Ministers the power to change pre-existing laws before exit day. This week's SIs range from European Structural Funds to clinical medical trials. The Prime Minister has until next Wednesday 27 February to make progress before MPs get another shot at wresting control over the Brexit process away from the government.