Upland Shores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

2002 Yearbook and Annual Report

2002 Yearbook and Annual Report Teaching individuals to take personal responsibility for all of their actions -The VYCC Mission Statement A Message from the President Dear Friends, I am pleased to report that the VYCC has never been stronger. We made it work with our extraordinary staff, board members, and volunteers who are extremely talented, committed, and a lot of fun to work with. Thank you! While this is a time when we can take great pride in our accomplishments, it is not a time when we can rest, even for a minute…the needs in our communities are greater than ever and growing, and the Thomas Hark with children Eli (left), VYCC is an important part of the answer. Zachary (middle), and newborn Rosie (right). Our mission of teaching individuals to take personal responsibility for their own actions, what one says and does, is absolutely vital and essential to creating strong and healthy communities. It is these lessons learned in the Corps that will make the difference in the years and decades to come. While it is true that we operate state parks and do incredible trail and other natural resource work, and that this work all by itself makes the VYCC vital to Vermont, the true value of this organization is what individuals learn from their experiences, and then take with them and use the rest of their lives…it is the values of respect, hard work, and personal responsibility that become imbedded in an individual after a stint in the Corps. Many people think of the VYCC as that small group who built a local trail…though few realize over 350 Staff and Corps Members were enrolled in 2002 and completed over 80,000 hours of important conservation work on 800 distinct projects in every corner of Vermont. -

Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada. James Murl Mccloy Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mccloy, James Murl, "Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1605. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1605 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-252 McCLOY, James Murl, 1934- MORPHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BLOW RIVER DELTA, YUKON TERRITORY, CANADA. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 Geography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Belta, Yukon Territory, Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by James Murl McCloy B.A., State College at Los Angeles, 1961 May, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research culminating in this dissertation was conducted under the auspices of the Arctic Institute of North America. The major portion of the financial support was received from the United States Army under contract no. BA-ARO-D-3I-I2I4.-G832, "Arctic Environmental Studies." Additional financial assistance during part of the writing stage was received in the form of a research assistantship from the Coastal Studies Institute, Louisi ana State University. -

Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20Th Century

u.s. Fish and Wildlife Service Co l\Ietland Trends In the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century November 2004 A National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century Ralph W. Tiner1, Irene J. Huber2, Todd Nuerminger2, and Aimée L. Mandeville3 1U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wetlands Inventory Program Northeast Region 300 Westgate Center Drive Hadley, MA 01035 2Natural Resources Assessment Group Department of Plant and Soil Sciences University of Massachusetts Stockbridge Hall Amherst, MA 01003 3Department of Natural Resources Science Environmental Data Center University of Rhode Island 1 Greenhouse Road, Room 105 Kingston, RI 02881 November 2004 National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report between U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, University of Rhode Island, and Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management This report should be cited as: Tiner, R.W., I.J. Huber, T. Nuerminger, and A.L. Mandeville. 2004. Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Northeast Region, Hadley, MA. In cooperation with the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and the University of Rhode Island. National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report. 37 pp. plus appendices. Table of Contents Page Introduction 1 Study Area 1 Methods 5 Data Compilation 5 Geospatial Database Construction and GIS Analysis 8 Results 9 Baywide 1996 Status 9 Coastal Wetlands and Waters 9 500-foot Buffer Zone 9 Baywide Trends 1951/2 to 1996 15 Coastal Wetland Trends 15 500-foot Buffer Zone Around Coastal Wetlands 15 Trends for Pilot Study Areas 25 Conclusions 35 Acknowledgments 36 References 37 Appendices A. -

New York State Artificial Reef Plan and Generic Environmental Impact

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................... vi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................1 2. MANAGEMENT ENVIRONMENT ..................4 2.1. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. ..............4 2.2. LOCATION. .....................7 2.3. NATURAL RESOURCES. .................7 2.3.1 Physical Characteristics. ..........7 2.3.2 Living Resources. ............. 11 2.4. HUMAN RESOURCES. ................. 14 2.4.1 Fisheries. ................. 14 2.4.2 Archaeological Resources. ......... 17 2.4.3 Sand and Gravel Mining. .......... 18 2.4.4 Marine Disposal of Waste. ......... 18 2.4.5 Navigation. ................ 18 2.5. ARTIFICIAL REEF RESOURCES. ............ 20 3. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .................. 26 3.1 GOALS ....................... 26 3.2 OBJECTIVES .................... 26 4. POLICY ......................... 28 4.1 PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION .............. 28 4.1.1 Permits. .................. 29 4.1.2 Materials Donations and Acquisitions. ... 31 4.1.3 Citizen Participation. ........... 33 4.1.4 Liability. ................. 35 4.1.5 Intra/Interagency Coordination. ...... 36 4.1.6 Program Costs and Funding. ......... 38 4.1.7 Research. ................. 40 4.2 DEVELOPMENT GUIDELINES .............. 44 4.2.1 Siting. .................. 44 4.2.2 Materials. ................. 55 4.2.3 Design. .................. 63 4.3 MANAGEMENT .................... 70 4.3.1 Monitoring. ................ 70 4.3.2 Maintenance. ................ 72 4.3.3 Reefs in the Exclusive Economic Zone. ... 74 4.3.4 Special Management Concerns. ........ 76 4.3.41 Estuarine reefs. ........... 76 4.3.42 Mitigation. ............. 77 4.3.43 Fish aggregating devices. ...... 80 i 4.3.44 User group conflicts. ........ 82 4.3.45 Illegal and destructive practices. .. 85 4.4 PLAN REVIEW .................... 88 5. ACTIONS ........................ 89 5.1 ADMINISTRATION .................. 89 5.2 RESEARCH ..................... 89 5.3 DEVELOPMENT .................... 91 5.4 MANAGEMENT .................... 96 6. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS ................. 97 6.1 ECOSYSTEM IMPACTS. -

Understanding the Temporal Dynamics of the Wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms EarthTemporal Surf. dynamicsProcess. Landforms of a wandering 30, 1227–1250 river (2005) 1227 Published online 23 June 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/esp.1196 Understanding the temporal dynamics of the wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada Leif M. Burge1* and Michel F. Lapointe2 1 Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University of Toronto, 100 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G3, Canada 2 Department of Geography McGill University, 805 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 2K6, Canada *Correspondence to: L. M. Burge, Abstract Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University Wandering rivers are composed of individual anabranches surrounding semi-permanent of Toronto, 100 St. George St., islands, linked by single channel reaches. Wandering rivers are important because they Toronto, M5S 3G3, Canada. provide habitat complexity for aquatic organisms, including salmonids. An anabranch cycle E-mail: [email protected] model was developed from previous literature and field observations to illustrate how anabranches within the wandering pattern change from single to multiple channels and vice versa over a number of decades. The model was used to investigate the temporal dynamics of a wandering river through historical case studies and channel characteristics from field data. The wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, was mapped from aerial photographs (1945, 1965, 1983 and 1999) to determine river pattern statistics and for historical analysis of case studies. Five case studies consisting of a stable single channel, newly formed anabranches, anabranches gaining stability following creation, stable anabranches, and an abandoning anabranch were investigated in detail. -

Appendix E Fish Habitat Utilization Literature Review

Appendix E Fish Habitat Utilization Literature Review East Kitsap Nearshore Assessment Appendix E Appendix E - Fish Habitat Utilization Literature Review Toft et al. (2007) City Shoreline Fish Distribution Study objective: study the abundance and behavior of juvenile salmon and other fishes among various marine shoreline habitat types near the city of Seattle. Focused on 5 types of shorelines - cobble beach - sand beach - riprap extending into the upper intertidal zone - deep riprap extending into the subtidal - edge of overwater structures Also examined stomach contents of juvenile salmon. Fish sampling methods included enclosure nets and snorkel surveys. Riprap often results in greater beach slopes and steep embankments which effectively reduces the intertidal zone. These characteristics in turn, result in habitat loss for juvenile flatfishes. At high intertidal habitats, more crab were encountered at cobble beaches compared to sand beaches and riprap. Demersal fishes (cottids) were found in greater numbers at riprap. Differences in species density between habitat type were more apparent for demersal fishes than for pelagic species. Densities of salmon were significantly different among habitat types. The highest densities occurred at the edge of overwater structures and in deep riprap. Deep riprap creates some structured habitat which seems to attract surfperches and gunnels. Threespine stickleback, tubesnout, and bay pipefish were also more prevalent at deep riprap than at cobble, sand, and high elevation riprap. Beamer et al. (2006) – Habitat and fish use of pocket estuaries in the Whidbey basin and north Skagit county bays, 2004 and 2005 Pocket estuaries are characterized as having more dilute marine water relative to the surrounding estuary. -

Southeast Region

VT Dept. of Forests, Parks and Recreation Mud Season Trail Status List is updated weekly. Please visit www.trailfinder.info for more information. Southeast Region Trail Name Parcel Trail Status Bear Hill Trail Allis State Park Closed Amity Pond Trail Amity Pond Natural Area Closed Echo Lake Vista Trail Camp Plymouth State Park Caution Curtis Hollow Road Coolidge State Forest (east) Open Slack Hill Trail Coolidge State Park Closed CCC Trail Coolidge State Park Closed Myron Dutton Trail Dutton Pines State Park Open Sunset Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Broad Brook Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Sunrise Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Kent Brook Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed Appalachian Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed Old Growth Interpretive Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed West River Trail Jamaica State Park Open Overlook Trail Jamaica State Park Closed Hamilton Falls Trail Jamaica State Park Closed Lowell Lake Trail Lowell Lake State Park Closed Gated Road Molly Beattie State Forest Closed Mt. Olga Trail Molly Stark State Park Closed Weathersfield Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Windsor Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Futures Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Mt. Ascutney Parkway Mt. Ascutney State Park Open Brownsville Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Gated Roads Muckross State Park Open Healdville Trail Okemo State Forest Closed Government Road Okemo State Forest Closed Mountain Road Okemo State Forest Closed Gated Roads Proctor Piper State Forest Open Quechee Gorge Trail Quechee Gorge State Park Caution VINS Nature Center Trail Quechee Gorge State Park Open Park Roads Silver Lake State Park Open Sweet Pond Trail Sweet Pond State Park Open Thetford Academy Trail Thetford Hill State Park Closed Gated Roads Thetford Hill State Park Open Bald Mt. -

Appendix a Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There

Appendix A Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There his list of places to visit is arranged by biophysical region. Within biophysical regions, the places are listed more or less north-to-south and by county. This list T includes all the places to visit that are mentioned in the natural community profiles, plus several more to round out an exploration of each biophysical region. The list of natural communities at each site is not exhaustive; only the communities that are especially well-expressed at that site are listed. Most of the natural communities listed are easily accessible at the site, though only rarely will they be indicated on trail maps or brochures. You, the naturalist, will need to do the sleuthing to find out where they are. Use topographic maps and aerial photographs if you can get them. In a few cases you will need to do some serious bushwhacking to find the communities listed. Bring your map and compass, and enjoy! Champlain Valley Franklin County Highgate State Park, Highgate Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation Temperate Calcareous Cliff Rock River Wildlife Management Area, Highgate Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Alder Swamp Missisquoi River Delta, Swanton and Highgate Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Protected with the assistance of The Nature Conservancy Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Lakeside Floodplain Forest Red or Silver Maple-Green Ash Swamp Pitch Pine Woodland Bog -

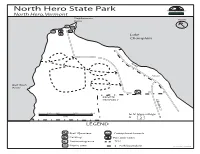

North Hero Map and Guide

North Hero State Park FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION VERMONT North Hero, Vermont AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES Stephenson North Point Lake Champlain PRIVATE PRIVATE Bull Rush Point PRIVATE PROPERTY Lakeview Dr. 0 150 300 600 900 to N. Hero village feet & 2 LEGEND Staff Quarters Cartop boat launch Parking Portable toilet Swimming area Trail Picnic area Park boundary ephelps-revised 03/2019 Isle LaMotte North Hero State Park ● St. Anne’s Shrine ● Ancient coral reef Welcome to North Hero State Park. Land for North Hero this 399-acre park was purchased in 1963. North Hero Nearly one-third of the land area lies below 100 ●Knight Point State Park feet in elevation. Lake Champlain normally State Park fluctuates from about 95 to 101 feet above sea Milton level, subjecting much of the park to seasonal ● Sand Bar State Park Map & Guide inundation. The forest type in the floodplain area is uncommon in Vermont, found only around Alburgh Lake Champlain. The lakeside floodplain forest ● Alburgh Dunes State Park at North Hero is noted for its size, relatively ● Lake Champlain Bikeways undisturbed condition and the valuable wildlife habitat it provides. For More Information contact: Wildlife habitat improvements at North Hero North Hero State Park State Park have yielded tangible results. White- 3803 Lakeview Drive tailed deer are common, as are a variety of North Hero, VT 05474 migratory waterfowl - mallards, black and wood (802) 372-8727 (Operating Season) ducks nest in the wooded wetlands. Ruffed Or Call grouse and American woodcock find suitable VT State Parks Reservations Center breeding and nesting habitat here as well. -

Brief Introduction Camp Plymouth State Park

State Parks In Vermont: Brief Introduction by newsdesk Camp Plymouth State Park :The site of Camp Plymouth was at one time thought to have been used as an encampment by soldiers of the Revolutionary War in 1777. The Boy Scouts used this area until 1984 when it became a state park. Camp Plymouth State Park is located in the town of Plymouth on the east shore of Echo Lake. The total acreage is 295 acres of which 46 acres comprise the developed portion of the park. The balance (249 acres) contains hiking trails, fishing, hunting, gold panning, and primitive camping, but is largely forestry oriented. Fort Dummer State Park :The park was named after Fort Dummer, the first permanent white settlement in Vermont. Built on the frontier in 1724, it was initially the gateway to the early settlements along the banks of the Connecticut River. Forty-three English soldiers and twelve Mohawk Indians manned the fort in 1724 and 1725. Later, the fort protected what was then a Massachusetts colony from an invasion by the French and Indians. Made of sturdy white pine timber, stacked like a log cabin, Fort Dummer served its purpose well. The park overlooks the site of Fort Dummer which was flooded when the Vernon Dam was built on the Connecticut River in 1908. This site can be seen from the northernmost scenic vista on the Sunrise Trail. It is now underwater near the lumber company located on the western bank of the river. Knight Point State Park :Knight Point on North Hero Island opened as a state park in 1978. -

Dune Nourishment Fact Sheet

StormSmart Coasts StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 1: Artificial Dunes and Dune Nourishment The coast is a very dynamic environment and coastal shorelines—especially beaches, dunes, and banks—change constantly in response to wind, waves, tides, and other factors such as seasonal variation, sea level rise, and human alterations to the shoreline system. Consequently, many coastal properties are at risk from storm damage, erosion, and flooding. Inappropriate shoreline stabilization methods can actually do more harm than good by exacerbating beach erosion, damaging neighboring properties, impacting marine habitats, and diminishing the capacity of beaches, dunes, and other natural landforms to protect inland areas from storm damage and flooding. StormSmart Properties—part of the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management’s (CZM) StormSmart Coasts program—provides coastal property owners with important information on a range of shoreline stabilization techniques that can effectively reduce erosion and storm damage while minimizing impacts to shoreline systems. This information is intended to help property owners work with consultants and other design professionals to select the best option for their circumstances. What Are Artificial Dunes and Dune Nourishment? A dune is a hill, mound, or ridge of sediment that No shoreline stabilization option permanently stops has been deposited by wind or waves landward of all erosion or storm damage. The level of protection a coastal beach. In Massachusetts, the sediments provided depends on the option chosen, project design, that form beaches and dunes range from sand to and site-specific conditions such as the exposure to gravel- and cobble-sized material. An artificial dune storms. All options require maintenance, and many is a shoreline protection option where a new mound also require steps to address adverse impacts to of compatible sediment (i.e., sediment of similar the shoreline system, called mitigation.