Variation in the Grass Pea (Lathyrus Sa Tivus L.' and Wild Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiple Polyploidy Events in the Early Radiation of Nodulating And

Multiple Polyploidy Events in the Early Radiation of Nodulating and Nonnodulating Legumes Steven B. Cannon,*,y,1 Michael R. McKain,y,2,3 Alex Harkess,y,2 Matthew N. Nelson,4,5 Sudhansu Dash,6 Michael K. Deyholos,7 Yanhui Peng,8 Blake Joyce,8 Charles N. Stewart Jr,8 Megan Rolf,3 Toni Kutchan,3 Xuemei Tan,9 Cui Chen,9 Yong Zhang,9 Eric Carpenter,7 Gane Ka-Shu Wong,7,9,10 Jeff J. Doyle,11 and Jim Leebens-Mack2 1USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Corn Insects and Crop Genetics Research Unit, Ames, IA 2Department of Plant Biology, University of Georgia 3Donald Danforth Plant Sciences Center, St Louis, MO 4The UWA Institute of Agriculture, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia 5The School of Plant Biology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia 6Virtual Reality Application Center, Iowa State University 7Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada 8Department of Plant Sciences, The University of Tennessee Downloaded from 9BGI-Shenzhen, Bei Shan Industrial Zone, Shenzhen, China 10Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada 11L. H. Bailey Hortorium, Department of Plant Biology, Cornell University yThese authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/ Associate editor:BrandonGaut Abstract Unresolved questions about evolution of the large and diverselegumefamilyincludethetiming of polyploidy (whole- genome duplication; WGDs) relative to the origin of the major lineages within the Fabaceae and to the origin of symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Previous work has established that a WGD affects most lineages in the Papilionoideae and occurred sometime after the divergence of the papilionoid and mimosoid clades, but the exact timing has been unknown. -

Ecogeographic, Genetic and Taxonomic Studies of the Genus Lathyrus L

ECOGEOGRAPHIC, GENETIC AND TAXONOMIC STUDIES OF THE GENUS LATHYRUS L. BY ALI ABDULLAH SHEHADEH A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Biosciences College of Life and Environmental Sciences University of Birmingham March 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Lathyrus species are well placed to meet the increasing global demand for food and animal feed, at the time of climate change. Conservation and sustainable use of the genetic resources of Lathyrus is of significant importance to allow the regain of interest in Lathyrus species in world. A comprehensive global database of Lathyrus species originating from the Mediterranean Basin, Caucasus, Central and West Asia Regions is developed using accessions in major genebanks and information from eight herbaria in Europe. This Global Lathyrus database was used to conduct gap analysis to guide future collecting missions and in situ conservation efforts for 37 priority species. The results showed the highest concentration of Lathyrus priority species in the countries of the Fertile Crescent, France, Italy and Greece. -

Lathlati FABA FINAL

Lathyrus latifolius L. Common Names: Perennial Pea (1), Everlasting Pea (2), Broad-leaved Everlasting Pea (3). Etymology: Lathyrus comes from Lathyros, a leguminous plant of Ancient Greece classified by Theophrastus and believed to be an aphrodisiac. “The name is often said to be composed of the prefix, la, very, and thuros, passionate.” (1). Latifolius means broad-leaved (4). Botanical synonyms: Lathyrus latifolius L. var. splendens Groenl. & Rumper (5) FAMILY: Fabaceae (the pea family) Quick Notable Features: ¬ Winged stem and petioles ¬ Leaves with only 2 leaflets ¬ Branched leaf-tip tendril ¬ Pink papilionaceous corolla (butterfly- like) Plant Height: Stem height usually reaching 2 m (7). Subspecies/varieties recognized: Lathyrus latifolius f. albiflorus Moldenke L. latifolius f. lanceolatus Freyn (5, 6): Most Likely Confused with: Other species in the genus Lathyrus, but most closely resembles L. sylvestris (2). May also possibly be confused with species of the genera Vicia and Pisum. Habitat Preference: A non-native species that has been naturalized along roadsides and in waste areas (7). Geographic Distribution in Michigan: L. latifolius is scattered throughout Michigan, in both the Upper and Lower Peninsula. In the Upper Peninsula it is found in Baraga, Gogebic, Houghton, Keweenaw, Mackinac, Marquette, Ontonagon, and Schoolcraft counties. In the Lower Peninsula it is found in the following counties: Alpena, Antrim, Benzie, Berrien, Calhoun, Cass, Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Clinton, Emmet, Genesee, Hillsdale, Isabella, Kalamazoo, Kalkaska, Kent, Leelanau, Lenawee, Livingston, Monroe, Montmorency, Newaygo, Oakland, Oceana, Ostego, Saginaw, Sanilac, Van Buren, Washtenaw, and Wayne (2, 5). At least one quarter of the county records are newly recorded since 1985: 29 county records were present in 1985 and there are 38 county- level records as of 2014. -

Prairie Garden

GARDEN PLANS Prairie Garden NATIVE PLANTS HELP MAKE THIS GARDEN NEARLY FOOLPROOF. One of the best things about planting native plants is that they are extraordinarily hardy and easy to grow. This prairie-inspired garden is a catalog of plants that Midwestern settlers would have found when they arrived. False blue indigo, wild petunia, prairie blazing star, and Indian grass are just a sample in this varied garden. Like the true prairie, this garden enjoys full sun and tolerates summer heat. Copyright Meredith Corporation WWW.BHG.COM/GARDENPLANS • PRAIRIE GARDEN • 1 Prairie Garden PLANT LIST A Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) (8) E Prairie Blazing Star (Liatris pycnostachya ) (5) Fine textured, emerald green leaves turn gold in fall, uniquely fragrant Wonderful showstopper! Purple-rose blooms in a spike form, blooming seed head. Zones 3-7, 2–4’ tall. from top down. Zones 4-7, 3-5’ tall. ALTERNATE PLANT ALTERNATE PLANT Sideoats Grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) Beardstongue (Penstemon digitalis) Short grass with small oat-like seeds on one side of the stalk. Long blooming, white flowers tinged pink in June and into summer. Zones 3-7, 2-3’ tall. Zones 4-7, 2-3’ tall. B Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) (3) F Downy Phlox (Phlox pilosa) (5) Blue-green foliage turns crimson in fall, fluffy silver seed heads. Bright pink flowers in spring, Zones 4-7, 12" tall. Zones 4-8, 2-3’ tall. ALTERNATIVE PLANT ALTERNATIVE PLANT Heath Aster (Aster ericoides) Western Sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis) Named this since it resembles heath, small white flowers in fall, Shorter of the native sunflowers, golden-yellow flowers on leafless stalks. -

Lathyrus Bijugatus

Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) FEIS Home Page Lathyrus bijugatus Table of Contents SUMMARY INTRODUCTION DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDIX REFERENCES Figure 1—Drypark pea in flower. Photo by Tara Luna, used with permission. SUMMARY This Species Review summarizes the scientific information that was available on drypark pea as of February 2021. Drypark pea is a rare, leguminous forb that occurs in eastern Washington and Oregon, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana. Within that distribution, it grows in a broad range of biogeoclimatic zones and elevations. As its common name "drypark pea" suggests, it prefers dry soils and open sites. Drypark pea grows in sagebrush-conifer and sagebrush-grassland transition zones; in ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, and subalpine fir-Engelmann spruce woodlands and forests; and subalpine fir parklands. In conifer communities, it is most common in open stands. Drypark pea has rhizomes that grow out from its taproot. Its roots host nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium bacteria. Drypark pea regenerates from seed and has a soil-stored seed bank; however, information on seed dispersal, viability, and seedling establishment of drypark pea was not available in the literature. Fire probably top-kills drypark pea, and it likely sprouts from its rhizomes and/or caudex after top-kill; however, these responses are undocumented. Only one study provided information on the response of drypark pea to fire. In ponderosa pine forest in northern Idaho, cover and frequency of drypark pea were similar on unburned plots and plots burned under low or high intensity, when 1 averaged across 3 postfire years. -

Diseases of Specific Florist Crops Geranium (Pelargonium Hortorum)

Diseases of Specific Florist Crops Keeping florist crops free of disease requires constant care and planning. Prevention is the basis of freedom from disease and should be an integral part of the general cultural program. The symptoms of the diseases of major florist crops are described individually by crop in a series of fact sheets. Geranium (Pelargonium hortorum) • Bacterial blight (Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii): Tiny (1/16 in. diameter) round brown leaf spots, often surrounded by a chlorotic zone. Spots form when bacteria have been splashed onto the leaf surface. Subsequent systemic invasion of the plant leads to the development of a yellow or tan wedge-shaped area at the leaf edge and then to wilting of the leaf. Further progression of the disease may lead to brown stem cankers at nodes, brown to black vascular discoloration inside the stem, and tip dieback or wilting of all or part of the plant. Roots usually remain healthy-looking. Disease symptoms develop most readily under warm (spring) greenhouse temperatures. Spread is rapid during the handling and overhead irrigation associated with propagation. Only geraniums are susceptible to bacterial blight. P. hortorum (zonal) and P. peltatum (ivy) both show symptoms; P. domesticum (Martha Washington or Regal) is less likely to show symptoms. Hardy Geranium species may also be a source of infection; these will show leaf spot but not wilt symptoms. Infested plants should be destroyed; there are no chemical controls. Although culture- indexing procedures should have eliminated this disease from modern geranium production, it remains all too common in the industry today, causing large financial losses to geranium growers. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

Adaptation of Grass Pea (Lathyrus Sativus Cv

Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus cv. Ceora) − adaptation to water deficit and benefit in crop rotation MARCAL GUSMAO M.Sc. School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Sciences The University of Adelaide This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences School of Plant Biology and The UWA Institute of Agriculture December 2010 i Abstract Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus cv. Ceora) is a multipurpose grain legume with an indeterminate growth habit. Adaptation of grass pea to water deficits and its potential rotational benefits in the Mediterranean-type environment of southern Australia are not well understood. The first objective of the thesis was to identify adaptation mechanisms of grass pea to water deficits. This was done by imposing water deficit during the reproductive period on plants grown in pots in a glasshouse. In the first experiment, a moderate water deficit was imposed on Ceora and a well-adapted field pea (Pisum sativum cv. Kaspa), by reducing soil water content from 80 to 50% field capacity (FC) during seed filling. Water deficit decreased pre-dawn leaf water potential (Ψ) of Ceora and Kaspa, as well as stomatal conductance (gs) of Ceora, but no reduction in photosynthesis occurred. Water deficit reduced green leaf area of Ceora resulting in 30 and 24% reduction in plant dry mass and seed yield at maturity, respectively. Seed size and harvest indices (HI) of Ceora did not differ between the treatments. Ceora produced more dry matter than Kaspa in both treatments, but produced 22 (control) and 33% (water deficit) lower seed yields. -

PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE INTRODUCTION to the FABACEAE

1 PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE In this lesson we will begin our study of the GENUS Phaseolus, a member of the Fabaceae family. The Fabaceae are also known as the Legume Family. We will learn about this family, the Fabaceae and some of the other LEGUMES. When we study about the GENUS and family a plant belongs to, we are studying its TAXONOMY. For this lesson to be complete you must: ___________ do everything in bold print; ___________ answer the questions at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the world map at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the table at the end of the lesson; ___________ learn to identify the different members of the Fabaceae (use the study materials at www.geauga4h.org); and ___________ complete one of the projects at the end of the lesson. Parts of the lesson are in underlined and/or in a different print. Younger members can ignore these parts. WORDS PRINTED IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS may be new vocabulary words. For help, see the glossary at the end of the lesson. INTRODUCTION TO THE FABACEAE The genus Phaseolus is part of the Fabaceae, or the Pea or Legume Family. This family is also known as the Leguminosae. TAXONOMISTS have different opinions on naming the family and how to treat the family. Members of the Fabaceae are HERBS, SHRUBS and TREES. Most of the members have alternate compound leaves. The FRUIT is usually a LEGUME, also called a pod. Members of the Fabaceae are often called LEGUMES. Legume crops like chickpeas, dry beans, dry peas, faba beans, lentils and lupine commonly have root nodules inhabited by beneficial bacteria called rhizobia. -

Sweet Pea Cut Flower Production in Utah Maegen Lewis, Melanie Stock, Tiffany Maughan, Dan Drost, Brent Black

October 2019 Horticulture/Small Acreage/2019-01pr Sweet Pea Cut Flower Production in Utah Maegen Lewis, Melanie Stock, Tiffany Maughan, Dan Drost, Brent Black Introduction heavy rain and snowfall. If the plastic is installed Sweet peas are a cool-season annual in Utah, and after heavy precipitation, moisture will be trapped cut flower production is improved with the use of in the tunnel and soil can remain too wet. This high tunnels. Sweet peas should be transplanted makes very early spring planting challenging and early in the spring and harvested until hot summer increases the risk of disease. temperatures decrease stem length and quality. Sweet peas require a strong trellis, high soil fertility, and frequent harvesting. Tunnel-grown sweet peas began producing 4 weeks earlier and had 15% more marketable stems than a field-grown comparison crop in North Logan, Utah. However, our hot, semi- arid climate, combined with insect pressure limited success in our trials. How to Grow Soil Preparation: For optimal growth, sweet peas require rich, well-drained soil. Incorporating an inch of compost into the soil prior to planting can increase fertility, drainage, and organic matter, without creating pH or salinity problems. Conduct a routine soil test to determine any soil nutrient needs prior to planting sweet peas. Soil testing is particularly important when planting in new locations, and should be repeated every 2 years. USU’s Analytical Laboratories performs soil tests. Pricing and information for collecting and submitting a sample is available on their website. For sweet peas grown in a high tunnel, begin planning and maintaining the high tunnel during the ©2019 Utah State Univ. -

Growing Fabulous Sweet Peas

Growing Fabulous Sweet Peas (Lathryrus Odoratus) What? Family: Papilionaceae (think “butterfly”) Genus: Lathyrus Odoratus (simply put, “fragrant and very exciting”) Species: Latifolius (loosely, a ”broad flower”) Botanist Credited: Theophrastus, a Greek philosopher, student of Aristotle Varieties: There are about 150 species of the Lathyrus genus. At one time there were about 300 hundred varieties but now, unfortunately, only about 50 are available. In other words...our exquisite sweet peas are “broad, exciting, butterfly-shaped flowers!” Although stories vary about its European history, the lovely sweet pea is thought to have been brought to Britain via a Sicilian monk who sent seeds to a Middlesex schoolmaster, Henry Eckford in the 19th century. Over a period of more than 30 years, Eckford crossed and selected sweet peas to produce large flowers (grandifolia). The Spencer family (of the Princess Di fame) later developed many of the varieties, in the Earl of Spencer’s garden at Althorp, Northamptonshire, the best known being the ‘Countess Spencer’. The varieties we see today which sport the Spencer name are descended from the Earl’s own gardens! The English are crazy about sweet peas, their “poor man’s orchids.” Long before our Bozeman Sweet Pea Festival was a seed in our pea-pickin’ brains, a 1911 London sweet pea contest boasted over 10,000 entries! If you spend any time on the internet researching sweet peas, you will observe that most of the in-depth information about sweet peas originates from Great Britain. As a matter of fact, the sweet pea wound itself so tightly around British culture that you will find sweet peas in a number of extremely collectible china patterns (particularly the Royal Winston), in prints and paintings, and, of course, in gardens everywhere. -

Nodulation of Lathyrus and Vicia Spp. in Non- Agricultural Soils in East Scotland Euan K

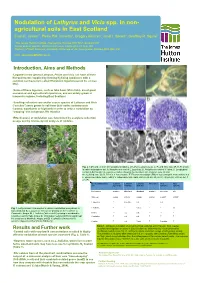

Nodulation of Lathyrus and Vicia spp. in non- agricultural soils in East Scotland Euan K. James1*, Pietro P.M. Iannetta1, Gregory Kenicer2, Janet I. Sprent3, Geoffrey R. Squire1 1The James Hutton Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, Scotland UK 2Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, UK 3Division of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at JHI, Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, UK Email: [email protected] Introduction, Aims and Methods • Legumes in the genera Lathyrus, Pisum and Vicia can have all their N-requirements supplied by forming N2-fixing symbioses with a common soil bacterium called Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. vicieae (Rlv). • Some of these legumes, such as faba bean (Vicia faba), are of great economical and agricultural importance, and are widely grown in temperate regions, including East Scotland. • Seedlings of native rare and/or scarce species of Lathyrus and Vicia (“vetches”) were grown in soil from their native environments (coastal, woodlands or highland) in order to induce nodulation by “trapping” the indigenous Rlv rhizobia. • Effectiveness of nodulation was determined by acetylene reduction assays and by microscopical analysis of nodules. Fig. 2. Light and electron micrographs of nodules of Lathyrus japonicus (A, C, E) and Vicia lutea (B, D, F) grown in native rhizosphere soil: A, Nodules on a root of L. japonicus; B, Nodules on a root of V. lutea; C, Longitudinal section (LS) through a L. japonicus nodule showing the meristem (m), invasion zone (it) and the N2-fixing zone (*); D, LS of a V. lutea nodule; E, Electron micrograph (EM) of a pleomorphic bacteroid (b) in a L.