ANTONIO VIVALDI: Concertos for Strings & Diverse Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

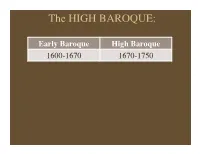

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Antonio Vivaldi Born: March 4, 1678 Died: July 28, 1741

“Spring” from The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi Born: March 4, 1678 Died: July 28, 1741 Antonio Vivaldi was born in institution became famous, Venice, Italy, which is where and people came from miles he spent most of his life. around the hear Vivaldi’s His father, a professional talented students perform the musician at St. Mark’s beautiful music he had written Church, taught him to play for them. the violin, and the two often performed together. Vivaldi was one of the best composers of his time. Although Vivaldi was He wrote operas, sonatas ordained a priest in the and choral works, but is Catholic Church (he was particularly known for his called the “Red Priest” concertos (he composed over because of his flaming 500, although many have red hair), health problems been lost). One of the most prevented him from famous sets is The Four celebrating the Mass and Seasons. After his death, he was not associated with Vivaldi’s music was virtually any one particular church. forgotten for many years. He continued to study However, in the early 1900’s, and practice the violin many of his original scores and became a teacher at were rediscovered and his a Venetian orphanage for popularity and reputation have young girls, a position continued to grow since that he held for the rest of his time. life. The orchestra of this Antonio Vivaldi Spring Spring has come, and joyfully 1. This concerto has a feeling of: the birds welcome it with cheerful song, and the streams, a. constant motion and change caressed by the breath of zephyrs, b. -

Unwrap the Music Concerts with Commentary

UNWRAP THE MUSIC CONCERTS WITH COMMENTARY UNWRAP VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS – SUMMER AND WINTER Eugenie Middleton and Peter Thomas UNWRAP THE MUSIC VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS SUMMER AND WINTER INTRODUCTION & INDEX This unit aims to provide teachers with an easily usable interactive resource which supports the APO Film “Unwrap the Music: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons – Summer and Winter”. There are a range of activities which will see students gain understanding of the music of Vivaldi, orchestral music and how music is composed. It provides activities suitable for primary, intermediate and secondary school-aged students. BACKGROUND INFORMATION CREATIVE TASKS 2. Vivaldi – The Composer 40. Art Tasks 3. The Baroque Era 45. Creating Music and Movement Inspired by the Sonnets 5. Sonnets – Music Inspired by Words 47. 'Cuckoo' from Summer Xylophone Arrangement 48. 'Largo' from Winter Xylophone Arrangement ACTIVITIES 10. Vivaldi Listening Guide ASSESSMENTS 21. Transcript of Film 50. Level One Musical Knowledge Recall Assessment 25. Baroque Concerto 57. Level Two Musical Knowledge Motif Task 28. Programme Music 59. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task 31. Basso Continuo 64. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task – 32. Improvisation Examples of Student Answers 33. Contrasts 69. Level Three Musical Knowledge Analysis Task 34. Circle of Fifths 71. Level Three Context Questions 35. Ritornello Form 36. Relationship of Rhythm 37. Wordfind 38. Terminology Task 1 ANTONIO VIVALDI The Composer Antonio Vivaldi was born and lived in Italy a musical education and the most talented stayed from 1678 – 1741. and became members of the institution’s renowned He was a Baroque composer and violinist. -

Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra to Perform June 1

Skip to Content Cal Poly News Search Cal Poly News Go California Polytechnic State University May 15, 2002 Contact: Jo Ann Lloyd (805) 756-1511 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra To Perform June 1 The Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra and some of the university's leading musicians and singers will perform music by Béla Bartók, Antonio Vivaldi, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Franz Schubert in its Spring Concert at 8 p.m. June 1 in the Theatre on campus. Founder and Music Professor Clifton Swanson will conduct the orchestra. Mi Young Shin, a 2000 graduate of the Cal Poly music program and assistant conductor of the orchestra, will lead the ensemble in a performance of Bartók's "Rumanian Dances," which include seven folk dances: the stick dance and sash dance, "in one spot," the horn dance, a Rumanian polka, and two fast dances. The orchestra will also perform with winners of the Music Department's solo competition, which was held in March. Recent Music Department graduate Jessica Getman, oboist, will perform the Allegro non molto from Vivaldi's Concerto in A minor for oboe and strings. In addition, three sopranos will perform. Business administration major Veronica Cull will sing "Stizzoso, mio stizzoso, voi fatte il borioso" from Pergolesi's "La Serva Padrona." Music major Valerie Laxson will perform Mozart's "Vedrai, carino, se sei buonino" from the opera "Don Giovanni." Music major Jennifer Cecil will sing the well-known "Alleluia" from Mozart's motet "Exsultate, jubilate," with Shin conducting. The concert will conclude with Schubert's Symphony No. -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

Roman REZNIK Delphine CONSTANTIN-REZNIK

Roman REZNIK | Delphine CONSTANTIN-REZNIK Roman REZNIK Delphine CONSTANTIN-REZNIK Henry ECCLES Antoine DARD Antonio VIVALDI Johann Sebastian BACH 1 This recording offers a nostalgic trip through 18th century Europe at the peak of the Baroque Dard played often in an opera orchestra, evidenced here in the way he uses the bassoon as a bel period. The bassoon and the harp were already popular instruments but it was very unusual canto tenor, often in a high register and with such technical difficulty that no one dared attempt for composers to write music for these two instruments together. Despite that, they unite in a similar techniques until much later. Still, his music is very lyrical and contains ornaments from the fascinating sound full of contrasts. so-called “style galant”. Like practically all Baroque music, the music on this CD includes works with “basso continuo” or figured bass which could be played by basically any instrument, in this case harp. In 1716 Antonio Vivaldi was appointed “maestro dei concerti” at the Ospedale della Pietá in Over time both the bassoon and the harp have gone through big changes, especially with regards Venice where he stayed for almost 20 years as music teacher at this famous school for illegitimate to register and the ability to play chromatically. The addition of the harp’s pedals made the or unwanted girls. Vivaldi composed numerous sonatas and concertos for various instruments instrument much more flexible and on a modern bassoon one can play much higher which makes for these apparently musically gifted students. Among these are cello sonatas. -

Estreno Mundial Del Motezuma De Vivaldi

A partir del descubrimiento sobre Vivaldi más importante en los últimos cincuenta años Estreno mundial del Motezuma de Vivaldi Gabriel Pareyón Rotterdam, 15 de junio [de 2005].- El fin de semana pasado se presentó en De Doelen, considerada la sala de conciertos más importante de esta ciudad holandesa, la ópera en tres actos Motezuma (1733), de Antonio Vivaldi (1678- 1741), en versión de concierto, sin decorados ni escenografía. La interpretación, que se anunció en todo el país como “estreno mundial”, estuvo a cargo del ensamble barroco Modo Antiguo, bajo la dirección de Federico María Sardelli. En realidad la ópera se estrenó el 14 de noviembre de 1733 en el teatro Sant’Angelo de Venecia, pero con tan mala fortuna que nunca se volvió a ejecutar hasta el sábado pasado, tras 271 años de silencio. Este largo período de olvido se debió principalmente a dos causas. Una de orden musical y otra fortuita. La primera ocurrió con el estreno mismo de la obra en que, al parecer, la mezzosoprano solista Anna Girò tuvo algunos problemas para cantar. Como resultado la prima donna de Vivaldi no volvería a interpretar ninguna ópera suya, a excepción de Il Tamerlano (1735). A ello se sumó cierto malestar del público, que tal vez juzgó la pieza “demasiado seria” (pues no hay siquiera un duo de amor ni ninguna danza) y que además esperaba del compositor, en vano, algún gesto de sumisión ante la poderosa novedad del estilo de Nápoles. Éste, conocido como “estilo galante”, significaría la vuelta de página entre las tendencias veneciana y napolitana, que se tradujo en el paso del barroco hacia el clasicismo (transición que en México representó Ignacio de Jerusalem [1707-1769] frente al estilo de Manuel de Sumaya [1676-1755]). -

Download Booklet

Delicate Delights BEST LOVED classical mandolin and lute music Delicate Delights Best loved classical mandolin and lute music 1 Johann Sebastian BACH (1675–1750) 6 Isaac ALBÉNIZ (1860–1909) Concerto in the Italian Style, 4:10 Suite española No. 1, Op. 47 – 6:23 BWV 971 ‘Italian Concerto’ – No. 5. Asturias (arr. for mandolin I. Allegro (arr. for mandolin and guitar) and guitar) Dorina Frati, Mandolin Jacob Reuven, Mandolin Piera Dadomo, Guitar (CDS514) Eyal Leber, Guitar (8.573566) 2 Antonio VIVALDI (1678–1741) 7 Tom G. FEBONIO (b. 1950) Mandolin Concerto in C major, 2:52 Water Ballads, Op. 47 – II. Sprite 2:29 RV 425 – I. Allegro Daniel Ahlert, Mandolin Paul O'Dette, Mandolin Birgit Schwab, Guitar (8.559686) The Parley of Instruments • Peter Holman (8.552101-02) 8 Johann HOFFMANN Mandolin Concerto in D major – 4:24 3 Johann HOFFMANN (1770–1814) III. Rondo Mandolin Sonata in D minor – 3:24 Elfriede Kunschak, Mandolin III. Allegro Vienna Pro Musica Orchestra Daniel Ahlert, Mandolin Vinzenz Hladky (CD3X-3022) Birgit Schwab, Archlute (8.557716) 9 Silvius Leopold WEISS (1686–1750) 4 Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Lute Sonata No. 14 in G minor – 4:07 Mandolin Sonatina in C major, 3:02 VI. Chaconne WoO 44 Daniel Ahlert, Mandolin Elfriede Kunschak, Mandolin Birgit Schwab, Baroque lute (8.557716) Maria Hinterleitner, Harpsichord (CD3X-3022) 10 Antonio VIVALDI Concerto for 2 Mandolins in G major, 3:12 5 Johann Sebastian BACH RV 532 – II. Andante Lute Suite in G minor, BWV 995 – 3:57 Silvia Tenchini and Dorina Frati, Mandolin III. Courante Mauro and Claudio Terroni Mandolin Orchestra Konrad Ragossnig, Lute (CD3X-3022) Dorina Frati, Conductor (CDS7787) 8.578183 2 11 Johann Sebastian BACH 16 Ermenegildo CAROSIO (1886–1928) Lute Partita in E major, BWV 1006a – 3:29 Flirtation Rag 4:18 III. -

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Ospedale della Pietà in Venice Opernhaus Prag Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Complete Opera – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Index - Complete Operas by Antonio Vivaldi Page Preface 3 Cantatas 1 RV687 Wedding Cantata 'Gloria e Imeneo' (Wedding cantata) 4 2 RV690 Serenata a 3 'Mio cor, povero cor' (My poor heart) 5 3 RV693 Serenata a 3 'La senna festegiante' 6 Operas 1 RV697 Argippo 7 2 RV699 Armida al campo d'Egitto 8 3 RV700 Arsilda, Regina di Ponto 9 4 RV702 Atenaide 10 5 RV703 Bajazet - Il Tamerlano 11 6 RV705 Catone in Utica 12 7 RV709 Dorilla in Tempe 13 8 RV710 Ercole sul Termodonte 14 9 RV711 Farnace 15 10 RV714 La fida ninfa 16 11 RV717 Il Giustino 17 12 RV718 Griselda 18 13 RV719 L'incoronazione di Dario 19 14 RV723 Motezuma 20 15 RV725 L'Olimpiade 21 16 RV726 L'oracolo in Messenia 22 17 RV727 Orlando finto pazzo 23 18 RV728 Orlando furioso 24 19 RV729 Ottone in Villa 25 20 RV731 Rosmira Fedele 26 21 RV734 La Silvia (incomplete) 27 22 RV736 Il Teuzzone 27 23 RV738 Tito Manlio 29 24 RV739 La verita in cimento 30 25 RV740 Il Tigrane (Fragment) 31 2 – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Preface In 17th century Italy is quite affected by the opera fever. The genus just newly created is celebrated everywhere. Not quite. For in Romee were allowed operas for decades heard exclusively in a closed society. The Papal State, who wanted to seem virtuous achieved at least outwardly like all these stories about love, lust, passions and all the ancient heroes and gods was morally rather questionable. -

Oboe Concertos

OBOE CONCERTOS LINER NOTES CD1-3 desire to provide the first recording of Vivaldi’s complete oboe Vivaldi: Oboe Concertos works. All things considered, even the concertos whose It is more than likely that Vivaldi’s earliest concertos for wind authenticity cannot be entirely ascertained reveal Vivaldi’s instruments were those he composed for the oboe. The Pietà remarkable popularity throughout Europe during the early years documents reveal a specific interest on his part for the of the 1700s, from Venice to Sweden, including Germany, instrument, mentioning the names of a succession of master Holland and England. If a contemporary publisher or composer oboists: Ignazio Rion, Ludwig Erdmann and Ignazio Sieber, as used the composer’s name in vain, perhaps attempting to well as Onofrio Penati, who had previously been a member of emulate his style, clearly he did so in the hope of improving his the San Marco orchestra. However, it was probably not one of chances of success, since Vivaldi was one of the most famous these musicians who inspired Vivaldi to write for the oboe, but and widely admired composers of his time. Indeed, in this sense instead the German soloist Johann Christian Richter, who was in imitation bears witness to the eminence of the original. Venice along with his colleagues Pisandel and Zelenka in 1716- Various problems regarding interpretation of text came to 1717, in the entourage of Prince Frederick Augustus of Saxony. the fore during the preparation of the manuscripts’ critical As C. Fertonani has suggested, Vivaldi probably dedicated the edition, with one possible source of ambiguity being Vivaldi’s Concerto RV455 ‘Saxony’ and the Sonata RV53 to Richter, who use of the expression da capo at the end of a movement (which may well have been the designated oboist for the Concerto was used so as to save him having to write out the previous RV447 as well, since this work also called for remarkable tutti’s parts in full).