Assessing Natural Resource Use Conflicts in the Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve, Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Monitoring and Conservation in a West African Protected Area by Andrew Cole Burton a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Wildlife Monitoring and Conservation in a West African Protected Area By Andrew Cole Burton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Justin S. Brashares, Chair Professor Steven R. Beissinger Professor Claire Kremen Professor William Z. Lidicker Fall 2010 Wildlife Monitoring and Conservation in a West African Protected Area © 2010 by Andrew Cole Burton ABSTRACT Wildlife Monitoring and Conservation in a West African Protected Area by Andrew Cole Burton Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Justin S. Brashares, Chair Global declines in biological diversity are increasingly well documented and threaten the welfare and resilience of ecological and human communities. Despite international commitments to better assess and protect biodiversity, current monitoring effort is insufficient and conservation targets are not being met (e.g., Convention on Biological Diversity 2010 Target). Protected areas are a cornerstone of attempts to shield wildlife from anthropogenic impact, yet their effectiveness is uncertain. In this dissertation, I investigated the monitoring and conservation of wildlife (specifically carnivores and other larger mammals) within the context of a poorly studied savanna reserve in a tropical developing region: Mole National Park (MNP) in the West African nation of Ghana. I first evaluated the efficacy of the park’s long-term, patrol-based wildlife monitoring system through comparison with a camera-trap survey and an assessment of sampling error. I found that park patrol observations underrepresented MNP’s mammal community, recording only two-thirds as many species as camera traps over a common sampling period. -

Kakum Natioanl Park & Assin Attadanso Resource Reserve

Kakum Natioanl Park & Assin Attadanso Resource Reserve Kakum and the Assin Attandanso reserves constitute a twin National Park and Resource Reserve. It was gazetted in 1991 and covers an area of about 350 km2 of the moist evergreen forest zone. The emergent trees are exceptionally high with some reaching 65 meters. The reserve has a varied wildlife with some 40 species of larger mammals, including elerpahnats, bongo, red riverhog, seven primates and four squirrels. Bird life is also varied. About 200 species are known to occur in the reserve and include 5 hornbil species, frazer-eagle owl, African grey and Senegal parrots. To date, over 400 species butterflies have been recorded. The Kakum National Park is about the most developed and subscribed eco-tourism site among the wildlife conservation areas. Nini Suhien National Park & Ankasa Resource Reserve Nini Suhien National Park and Ankasa Resources Reserve are twin Wildlife Protected Areas that are located in the wet evergreen forest area of the Western Region of Ghana. These areas are so rich in biodiversity that about 300 species of plants have been recorded in a single hectare. The areas are largely unexplored but 43 mammal species including the bongo, forest elephant, 10 primate species including the endangered Dina monkey and the West African chimpanzee have been recorded. Bird fauna is also rich. The reserves offer very good example of the west evergreen forest to the prospective tourist. The Mole national This park was established in 1958 and re-designated a National Park in 1971. It covers an area of 4,840 km2of undulating terrain with steep scarps. -

An Exploration of Policy Implementation in Protected

AN EXPLORATION OF POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN PROTECTED WATERSHED AREAS: CASE STUDY OF DIGYA NATIONAL PARK IN THE VOLTA LAKE MARGINS IN GHANA A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Jesse S. Ayivor March 2007 This thesis entitled AN EXPLORATION OF POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN PROTECTED WATERSHED AREAS: CASE STUDY OF DIGYA NATIONAL PARK IN THE VOLTA LAKE MARGINS IN GHANA by JESSE S. AYIVOR has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by Nancy J. Manring Associate Professor of Political Science Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Abstract AYIVOR, JESSE S., M.S., March 2007, Program of Environmental Studies AN EXPLORATION OF POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN PROTECTED WATERSHED AREAS: CASE STUDY OF DIGYA NATIONAL PARK IN THE VOLTA LAKE MARGINS IN GHANA (133 pp.) Director of Thesis: Nancy J. Manring The demise of vital ecosystems has necessitated the designation of protected areas and formulation of policies for their sustainable management. This study which evaluates policy implementation in Digya National Park in the Volta Basin of Ghana, was prompted by lack of information on how Ghana Forest and Wildlife policy, 1994, which regulates DNP, is being implemented amidst continues degradation of the Park. The methodology adopted involved interviews with government officials and analysis of institutional documents. The results revealed that financial constraints and encroachment are the main problems inhibiting the realization of the policy goals, resulting in a steady decrease in forest cover within the Park. -

Protected Area Governance and Its Influence on Local Perceptions

land Article Protected Area Governance and Its Influence on Local Perceptions, Attitudes and Collaboration Jesse Sey Ayivor 1,*, Johnie Kodjo Nyametso 2 and Sandra Ayivor 3 1 Institute for Environment and Sanitation Studies, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana 2 Department of Environment and Development Studies, Central University, Accra, Ghana; [email protected] 3 College of Education and Human Services, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26505, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: jsayivor@staff.ug.edu.gh; Tel.: +233-244213287 Received: 23 June 2020; Accepted: 30 August 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: Globally, protected areas are faced with a myriad of threats emanating principally from anthropogenic drivers, which underpins the importance of the human element in protected area management. Delving into the “exclusive” and “inclusive” approaches to nature conservation discourse, this study explored the extent to which local communities collaborate in the management of protected areas and how the governance regime of these areas influences local perceptions and attitudes. Data for the study were collected through stakeholder interviews, focus group discussions as well as a probe into participating groups’ collective perceptions and opinions on certain key issues. A total of 51 focus group discussions were held in 45 communities involving 630 participants. The analysis was done using qualitative methods and simple case counts to explain levels of acceptance or dislike of issues. The results showed that the objectives of state-managed protected areas, by their nature, tend to exclude humans and negatively influence local perceptions and attitudes. This, in addition to human-wildlife conflicts and high handedness by officials on protected area offenders, affects community collaboration. -

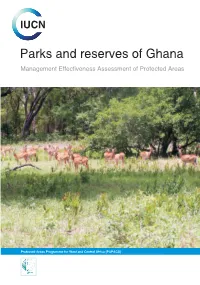

Ghana Management Effectiveness Assessment of Protected Areas

IUCN Parks and reserves of Ghana Management Effectiveness Assessment of Protected Areas Protected Areas Programme for West and Central Africa (PAPACO) Parks and reserves of Ghana Management Effectiveness Assessment of Protected Areas IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature 2010 3 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Copyright: © 2010 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: UICN/PACO (2010). Parks and reserves of Ghana : Management effectiveness assessment of protected areas. Ouagadougou, BF : UICN/PACO. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1277-2 Cover photos: Wildlife Division (Ghana) Produced by: UICN-PACO - Protected Areas Programme (www.papaco.org) Printed by: JAMANA Services, Tél. : +226 50 30 12 73 Available from: UICN – Programme Afrique Centrale et Occidentale (PACO) 01 BP 1618 Ouagadougou 01 Burkina Faso Tel: +226 50 36 49 79 / 50 36 48 95 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.iucn.org and www.papaco.org 4 CONTENTS SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. -

UPPER GUINEAN FOREST ECOSYSTEM of the GUINEAN FORESTS of WEST AFRICA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT

Ecosystem Profile UPPER GUINEAN FOREST ECOSYSTEM Of the GUINEAN FORESTS OF WEST AFRICA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT Final version december 14, 2000 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND: THE GUINEAN FOREST HOTSPOT ...........................................................4 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE GUINEAN FOREST HOTSPOT ...............................5 The Coastal Connection.............................................................................................................6 Levels of Species Diversity, Endemism and Flagship Species for Conservation .....................6 Levels of Protection for Biodiversity.........................................................................................9 THREAT ASSESSMENT ...........................................................................................................10 The Effects of Poverty .............................................................................................................10 Tropical Rainforest Loss and Fragmentation: The Effects of Agriculture, Logging and Population Growth...................................................................................................................11 Ecosystem Degradation: The Effects of Mineral Extraction, Hunting and Overharvesting ...12 Limited Local Capacity for Conservation: The Effects of Insufficient Professional Resources and Minimal Biodiversity Information....................................................................................13 -

Biodiversity Threats Assessment of the Western Region of Ghana”

BIODIVERSITY THREATS ASSESSMENT FOR THE WESTERN REGION OF GHANA INTEGRATED COASTAL AND FISHERIES GOVERNANCE INITIATIVE FOR THE WESTERN REGION OF GHANA Cooperative agreement # 641-A-00-09-00036-00 Implemented by the Coastal Resources Center University of Rhode Island In partnership with: The Government of Ghana Friends of the Nation SustainaMetrix The WorldFish Center APRIL 2010 This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website: www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA. Email: [email protected] Citation: K.A.A. deGraft-Johnson, J. Blay, F.K.E. Nunoo, C.C. Amankwah, 2010. “Biodiversity Threats Assessment of the Western Region of Ghana”. The Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance (ICFG) Initiative Ghana. Cover Photos: Coastline of Princess Town (Left); Fish landing site at Dixcove (Right) Western Region, Ghana. Photo Credits: F. K. E. Nunoo Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the consultation and support provided by the Integrated Coastal Fisheries Governance (ICFG) team. Special thanks go to Dr. Brian Crawford of the Coastal Resources Center (CRC) at the University of Rhode Island, USA, and personnel of the CRC offices in Ghana—Dr. Mark Fenn, Program Director, Mr. Kofi Agbogah, Deputy Program Director, and Mr. Harry Barnes Dabban, National Policy Coordinator. We appreciate and thank as well the stakeholders from Ghana, especially the Western Region who assisted with interviews, and documents which helped to develop this report. This report was produced as part of The Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance (ICFG) Initiative, Ghana—a four-year initiative supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). -

Canadian Curriculum Guide 2016

Once known as the “Gold Coast,” today Ghana is hailed as the golden country of West Africa. It is located in West Africa and uniquely positioned on the globe. The Greenwich Meridian at zero degrees longitude passes through the city of Tema, and the equator cuts just few degrees south of Ghana. Therefore, if you step on the intersection of the Longitude and the Latitude, and in whichever direction you move, Ghana is the first landmass you would step on. That is why it is often said that, Ghana is closer to the center of the earth than any other country. Truly one of Africa's great success stories, Ghana is reaping the benefits of a stable democracy, a strong economy and a rapidly exploding tourism industry fueled by forts and castles, beautiful landscapes, many teeming with exotic wildlife, national parks, unique art and music communities, and exciting experiences among many indigenous cultural groups. Ghana is also suffused with the most incredible energy. When you visit the Republic of Ghana, you might come face to face with caracals (wild cats) and cusimanses, bongos (deer) and bushbacks. Learn from and celebrate with such ethic groups as the Fante, the Ashanti, the Mole-Dagbon or the Ewe. Shop the markets of Kejetia in Kumasi or Makola in Accra. Take time to visit the Wechiau Hippo Sanctuary, the Tafi Atome Monkey Sancuary, or even stop by Paga and feed the crocodiles. Visit the Larabanga Mosque which dates to 1421, the Nzulezu village on stilts, the Colonial lighthouse of Jamestown, or the National Theatre in Accra. -

Download Date 27/09/2021 07:28:25

Draft Environmental Report on Ghana Item Type text; Book; Report Authors Turner, Sandra J.; University of Arizona. Arid Lands Information Center. Publisher U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat, Department of State (Washington, D.C.) Download date 27/09/2021 07:28:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/228234 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT ON GHANA prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 National Park Service Contract No. CX- 0001 -0 -0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of State Washington, D.C. October 1980 SUMMARY The environmental problems of Ghana center around intensive land use practices. Expanding patterns of vegetation change and environmental degradation are decreasing the carrying capacity of the land for both livestock and human populations. The effects of intensive resource utilization are exacerbated by expanding human needs and economic insta- bility, which cause hardship to much of the population. The major environmental problems faced by Ghana at present are: 1. Soil damage and loss resulting from overgrazing, agricul- tural practices and forest degradation. Continued pressure on the soil resource is increasing the rate of soil loss and is reducing fertility. Rangelands, agricultural lands and forest lands are seriously endangered. 2. Deforestation and desertification resulting from the whole system of degrading land use practices and harsh climate, including the overharvesting of trees for fuel. 3. Inadequate and hazardous water supplies resulting from climatic and geologic conditions coupled with water use practices which promote the spread of communicable disease. 4. Increasing industrial pollution resulting from resource development without environmental safeguards or planning. -

Canadian Curriculum Guide 2016

Once known as the “Gold Coast,” today Ghana is hailed as the golden country of West Africa. It is located in West Africa and uniquely positioned on the globe. The Greenwich Meridian at zero degrees longitude passes through the city of Tema, and the equator cuts just few degrees south of Ghana. Therefore, if you step on the intersection of the Longitude and the Latitude, and in whichever direction you move, Ghana is the first landmass you would step on. That is why it is often said that, Ghana is closer to the center of the earth than any other country. Truly one of Africa's great success stories, Ghana is reaping the benefits of a stable democracy, a strong economy and a rapidly exploding tourism industry fueled by forts and castles, beautiful landscapes, many teeming with exotic wildlife, national parks, unique art and music communities, and exciting experiences among many indigenous cultural groups. Ghana is also suffused with the most incredible energy. When you visit the Republic of Ghana, you might come face to face with caracals (wild cats) and cusimanses, bongos (deer) and bushbacks. Learn from and celebrate with such ethic groups as the Fante, the Ashanti, the Mole-Dagbon or the Ewe. Shop the markets of Kejetia in Kumasi or Makola in Accra. Take time to visit the Wechiau Hippo Sanctuary, the Tafi Atome Monkey Sancuary, or even stop by Paga and feed the crocodiles. Visit the Larabanga Mosque which dates to 1421, the Nzulezu village on stilts, the Colonial lighthouse of Jamestown, or the National Theatre in Accra. -

Canadian Curriculum Guide 2016

Once known as the “Gold Coast,” today Ghana is hailed as the golden country of West Africa. It is located in West Africa and uniquely positioned on the globe. The Greenwich Meridian at zero degrees longitude passes through the city of Tema, and the equator cuts just few degrees south of Ghana. Therefore, if you step on the intersection of the Longitude and the Latitude, and in whichever direction you move, Ghana is the first landmass you would step on. That is why it is often said that, Ghana is closer to the center of the earth than any other country. Truly one of Africa's great success stories, Ghana is reaping the benefits of a stable democracy, a strong economy and a rapidly exploding tourism industry fueled by forts and castles, beautiful landscapes, many teeming with exotic wildlife, national parks, unique art and music communities, and exciting experiences among many indigenous cultural groups. Ghana is also suffused with the most incredible energy. When you visit the Republic of Ghana, you might come face to face with caracals (wild cats) and cusimanses, bongos (deer) and bushbacks. Learn from and celebrate with such ethic groups as the Fante, the Ashanti, the Mole-Dagbon or the Ewe. Shop the markets of Kejetia in Kumasi or Makola in Accra. Take time to visit the Wechiau Hippo Sanctuary, the Tafi Atome Monkey Sancuary, or even stop by Paga and feed the crocodiles. Visit the Larabanga Mosque which dates to 1421, the Nzulezu village on stilts, the Colonial lighthouse of Jamestown, or the National Theatre in Accra. -

Biodiversity Threats Assessment for the Western Region of Ghana Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance Initiative for the Western Region of Ghana

BIODIVERSITY THREATS ASSESSMENT FOR THE WESTERN REGION OF GHANA INTEGRATED COASTAL AND FISHERIES GOVERNANCE INITIATIVE FOR THE WESTERN REGION OF GHANA Cooperative agreement # 641-A-00-09-00036-00 Implemented by the Coastal Resources Center University of Rhode Island In partnership with: The Government of Ghana Friends of the Nation SustainaMetrix The WorldFish Center APRIL 2010 This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website: www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA. Email: [email protected] Citation: K.A.A. deGraft-Johnson, J. Blay, F.K.E. Nunoo, C.C. Amankwah, 2010. “Biodiversity Threats Assessment of the Western Region of Ghana”. The Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance (ICFG) Initiative Ghana. Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cover Photos: Coastline of Princess Town (Left); Fish landing site at Dixcove (Right) Western Region, Ghana. Photo Credits: F. K. E. Nunoo Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the consultation and support provided by the Integrated Coastal Fisheries Governance (ICFG) team. Special thanks go to Dr. Brian Crawford of the Coastal Resources Center (CRC) at the University of Rhode Island, USA, and personnel of the CRC offices in Ghana—Dr. Mark Fenn, Program Director, Mr. Kofi Agbogah, Deputy Program Director, and Mr. Harry Barnes Dabban, National Policy Coordinator.