Breaking Sound Barriers: New Perspectives on Effective Big Band

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (Guest Post)*

“Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (guest post)* Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie The jazz standard “Manteca” was the product of a collaboration between Charles Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie and Cuban musician, composer and dancer Luciano (Chano) Pozo González. “Manteca” signified one of the beginning steps on the road from Afro-Cuban rhythms to Latin jazz. In the years leading up to 1940, Cuban rhythms and melodies migrated to the United States, while, simultaneously, the sounds of American jazz traveled across the Caribbean. Musicians and audiences acquainted themselves with each other’s musical idioms as they played and danced to rhumba, conga and big-band swing. Anthropologist, dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham was instrumental in bringing several Cuban drummers who performed in authentic style with her dance troupe in New York in the mid-1940s. All this laid the groundwork for the fusion of jazz and Afro-Cuban music that was to occur in New York City in the 1940s, which brought in a completely new musical form to enthusiastic audiences of all kinds. This coming fusion was “in the air.” A brash young group of artists looking to push jazz in fresh directions began to experiment with a radical new approach. Often playing at speeds beyond the skills of most performers, the new sound, “bebop,” became the proving ground for young New York jazz musicians. One of them, “Dizzy” Gillespie, was destined to become a major force in the development of Afro-Cuban or Latin jazz. Gillespie was interested in the complex rhythms played by Cuban orchestras in New York, in particular the hot dance mixture of jazz with Afro-Cuban sounds presented in the early 1940s by Mario Bauzá and Machito’s Afrocubans Orchestra which included singer Graciela’s balmy ballads. -

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42Nd ANNUAL

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42nd ANNUAL JUNE 2019 DOWNBEAT 95 JeJenna McLean, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is the Graduate College Wininner in the Vocal Jazz Soloist category. She is also the recipient of an Outstanding Arrangement honor. 42nd Student Music Awards WELCOME TO THE 42nd ANNUAL DOWNBEAT STUDENT MUSIC AWARDS The UNT Jazz Singers from the University of North Texas in Denton are a winner in the Graduate College division of the Large Vocal Jazz Ensemble category. WELCOME TO THE FUTURE. WE’RE PROUD after year. (The same is true for certain junior to present the results of the 42nd Annual high schools, high schools and after-school DownBeat Student Music Awards (SMAs). In programs.) Such sustained success cannot be this section of the magazine, you will read the attributed to the work of one visionary pro- 102 | JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL SOLOIST names and see the photos of some of the finest gram director or one great teacher. Ongoing young musicians on the planet. success on this scale results from the collec- 108 | LARGE JAZZ ENSEMBLE Some of these youngsters are on the path tive efforts of faculty members who perpetu- to becoming the jazz stars and/or jazz edu- ally nurture a culture of excellence. 116 | VOCAL JAZZ SOLOIST cators of tomorrow. (New music I’m cur- DownBeat reached out to Dana Landry, rently enjoying includes the 2019 albums by director of jazz studies at the University of 124 | BLUES/POP/ROCK GROUP Norah Jones, Brad Mehldau, Chris Potter and Northern Colorado, to inquire about the keys 132 | JAZZ ARRANGEMENT Kendrick Scott—all former SMA competitors.) to building an atmosphere of excellence. -

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: a Pedagogical Study

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2019 Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study Lara Marie Moline Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Moline, Lara Marie, "Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study" (2019). Dissertations. 576. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/576 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 LARA MARIE MOLINE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School VOCAL JAZZ IN THE CHORAL CLASSROOM: A PEDAGOGICAL STUDY A DIssertatIon SubMItted In PartIal FulfIllment Of the RequIrements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Lara Marie MolIne College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music May 2019 ThIs DIssertatIon by: Lara Marie MolIne EntItled: Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study has been approved as meetIng the requIrement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of VIsual and Performing Arts In School of Music, Program of Choral ConductIng Accepted by the Doctoral CoMMIttee _________________________________________________ Galen Darrough D.M.A., ChaIr _________________________________________________ Jill Burgett D.A., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Oravitz Ph.D., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Welsh Ph.D., Faculty RepresentatIve Date of DIssertatIon Defense________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School ________________________________________________________ LInda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and InternatIonal AdMIssions Research and Sponsored Projects ABSTRACT MolIne, Lara Marie. -

Baltimore Symphony Open Rehearsals

Baltimore Symphony Open Rehearsals Thank you for your interest to attend the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) Open Rehearsal series for students at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. The BSO Open Rehearsal series is an incredible opportunity to listen in to a working rehearsal of a professional symphony orchestra. This is a fantastic experience for young musicians (HS, MS, & college) to hear the process of the orchestra and conductor as they prepare for a performance. It can provide valuable insight for students who are already classical music lovers and performers. Each rehearsal is 2.5 hours, with a 20-minute break, about half-way through the rehearsal. The conductor may opt to stop and start the music. Some pieces may not be played in their entirety, and some pieces may be skipped altogether. Oftentimes, when the conductor stops, there will be dialogue between the conductor and the musicians, or between the musicians. Unfortunately, this dialogue is often difficult to hear in the audience. We suggest reviewing rehearsal/concert etiquette with your students before arriving at the hall. Any distractions are very disruptive to the musicians on stage and jeopardize our ability to offer this exclusive opportunity to students in the future. While an incredibly meaningful experience for some, it may not be the ideal listening experience for everyone. It is first and foremost a working rehearsal for the orchestra and offers observers a window into that experience with professionals. Younger students or students without a music background are strongly encouraged to attend the BSO’s Midweek series. The Midweek Concerts are curated performances specifically designed for students, and provide a welcoming, inviting, and encouraging way to experience a symphony orchestra. -

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD a NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most Books and Article

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD A NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE MARK OSTEEN, LOYOLA COLLEGE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most books and articles with "jazz" in the title are not simply about music. Instead, their authors generally use jazz music to investigate or promulgate ideas about politics or race (e.g., that jazz exemplifies democratic or American values,* or that jazz epitomizes the history of twentieth-century African Americans); to illustrate a philosophy of art (either a Modernist one or a Romantic one); or to celebrate the music as an expression of broader human traits such as conversa- tion, flexibility, and hybridity (here "improvisation" is generally the touchstone). These explorations of the broader cultural meanings of jazz constitute what is being touted as the New Jazz Studies. This proliferation of the meanings of "jazz" is not a bad thing, and in any case it is probably inevitable, for jazz has been employed as an emblem of every- thing but mere music almost since its inception. As Lawrence Levine demon- strates, in its formative years jazz—with its vitality, its sexual charge, its use of new technologies of reproduction, its sheer noisiness—was for many Americans a symbol of modernity itself (433). It was scandalous, lowdown, classless, obscene, but it was also joyous, irrepressible, and unpretentious. The music was a battlefield on which the forces seeking to preserve European high culture met the upstarts of popular culture who celebrated innovation, speed, and novelty. It 'Crouch writes: "the demands on and respect for the individual in the jazz band put democracy into aesthetic action" (161). -

JUBILEE EDITION to His Artistic Choice

WINTE R&WINTER JthUe fBirsIt L30EyE earsE1D98I5 T–I2O01N 5 SOUND JOURNEYS 30 Years of Music Recordings by Stefan Winter It is a kind of stage anniversary behind the scenes: 30 years ago Stefan Winter founds the JMT (Jazz Music Today) label and records the debut production of the young saxo - STEFAN WINTER AND MARIKO TAKAHASHI phonist Steve Coleman . The starting point is the new Afro-American conception M-Base . The protagonists of this movement are Cassandra Wilson (vocals), Geri Allen (piano), Robin Eubanks (trombone), Greg Osby and Gary Thomas (sax ophones). In antithesis to this artistic movement Winter do cu ments the development of the young jazz avant- garde and produces path-breaking recordings with Tim Berne (saxophone), Hank Roberts (cello), Django Bates (piano), Joey Baron (drums), Marc Ducret (guitar) and the ensemble Miniature . After 1995 his working method changes fundamentally from a documentarist to a sound director. This is the actual beginning of WINTER&WINTER. Together with Mariko Takahashi he dares to implement a new label concept. At the end of the 80s, Stefan Winter and Mariko Takahashi meet in Japan. Under the direction of Mariko Takahashi the festival »Taboo-Lu« is initiated in Ginza in Tokyo (Japan), a notable presentation with live concerts, an art exhibition and recordings. With »Taboo-Lu« the idea of and for WINTER&WINTER is quasi anticipated: Border crossing becomes a programme. Art and music cooperate together, contemporary meets tradition, composition improvisation. Mariko Takahashi and Stefan Winter want to open the way with unconventional recordings and works for fantastic and new experiences. Stefan Winter has the vision to produce classical masterpieces in radical new interpretations. -

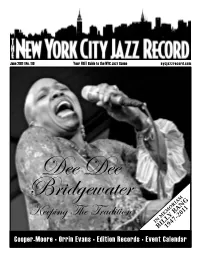

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition.