SOUND ATTENUATION in DUCTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition and Measurement of Sound Energy Level of a Transient Sound Source

J. Acoust. Soc. Jpn. (E) 8, 6 (1987) Definition and measurement of sound energy level of a transient sound source Hideki Tachibana,* Hiroo Yano,* and Koichi Yoshihisa** *Institute of Industrial Science , University of Tokyo, 7-22-1, Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 106 Japan **Faculty of Science and Technology, Meijo University, 1-501, Shiogamaguti, Tenpaku-ku, Nagoya, 468 Japan (Received 1 May 1987) Concerning stationary sound sources, sound power level which describes the sound power radiated by a sound source is clearly defined. For its measuring methods, the sound pressure methods using free field, hemi-free field and diffuse field have been established, and they have been standardized in the international and national stan- dards. Further, the method of sound power measurement using the sound intensity technique has become popular. On the other hand, concerning transient sound sources such as impulsive and intermittent sound sources, the way of describing and measuring their acoustic outputs has not been established. In this paper, therefore, "sound energy level" which represents the total sound energy radiated by a single event of a transient sound source is first defined as contrasted with the sound power level. Subsequently, its measuring methods by two kinds of sound pressure method and sound intensity method are investigated theoretically and experimentally on referring to the methods of sound power level measurement. PACS number : 43. 50. Cb, 43. 50. Pn, 43. 50. Yw sources, the way of describing and measuring their 1. INTRODUCTION acoustic outputs has not been established. In noise control problems, it is essential to obtain In this paper, "sound energy level" which repre- the information regarding the noise sources. -

Sound Power Measurement What Is Sound, Sound Pressure and Sound Pressure Level?

www.dewesoft.com - Copyright © 2000 - 2021 Dewesoft d.o.o., all rights reserved. Sound power measurement What is Sound, Sound Pressure and Sound Pressure Level? Sound is actually a pressure wave - a vibration that propagates as a mechanical wave of pressure and displacement. Sound propagates through compressible media such as air, water, and solids as longitudinal waves and also as transverse waves in solids. The sound waves are generated by a sound source (vibrating diaphragm or a stereo speaker). The sound source creates vibrations in the surrounding medium. As the source continues to vibrate the medium, the vibrations propagate away from the source at the speed of sound and are forming the sound wave. At a fixed distance from the sound source, the pressure, velocity, and displacement of the medium vary in time. Compression Refraction Direction of travel Wavelength, λ Movement of air molecules Sound pressure Sound pressure or acoustic pressure is the local pressure deviation from the ambient (average, or equilibrium) atmospheric pressure, caused by a sound wave. In air the sound pressure can be measured using a microphone, and in water with a hydrophone. The SI unit for sound pressure p is the pascal (symbol: Pa). 1 Sound pressure level Sound pressure level (SPL) or sound level is a logarithmic measure of the effective sound pressure of a sound relative to a reference value. It is measured in decibels (dB) above a standard reference level. The standard reference sound pressure in the air or other gases is 20 µPa, which is usually considered the threshold of human hearing (at 1 kHz). -

Sound Waves Sound Waves • Speed of Sound • Acoustic Pressure • Acoustic Impedance • Decibel Scale • Reflection of Sound Waves • Doppler Effect

In this lecture • Sound waves Sound Waves • Speed of sound • Acoustic Pressure • Acoustic Impedance • Decibel Scale • Reflection of sound waves • Doppler effect Sound Waves (Longitudinal Waves) Sound Range Frequency Source, Direction of propagation Vibrating surface Audible Range 15 – 20,000Hz Propagation Child’’s hearing 15 – 40,000Hz of zones of Male voice 100 – 1500Hz alternating ------+ + + + + compression Female voice 150 – 2500Hz and Middle C 262Hz rarefaction Concert A 440Hz Pressure Bat sounds 50,000 – 200,000Hz Wavelength, λ Medical US 2.5 - 40 MHz Propagation Speed = number of cycles per second X wavelength Max sound freq. 600 MHz c = f λ B Speed of Sound c = Sound Particle Velocity ρ • Speed at which longitudinal displacement of • Velocity, v, of the particles in the particles propagates through medium material as they oscillate to and fro • Speed governed by mechanical properties of c medium v • Stiffer materials have a greater Bulk modulus and therefore a higher speed of sound • Typically several tens of mms-1 1 Acoustic Pressure Acoustic Impedance • Pressure, p, caused by the pressure changes • Pressure, p, is applied to a molecule it induced in the material by the sound energy will exert pressure the adjacent molecule, which exerts pressure on its c adjacent molecule. P0 P • It is this sequence that causes pressure to propagate through medium. • p= P-P0 , (where P0 is normal pressure) • Typically several tens of kPa Acoustic Impedance Acoustic Impedance • Acoustic pressure increases with particle velocity, v, but also depends -

Aircraft Noise (Excerpt from the Oakland International Airport Master Plan Update – 2006)

Aircraft Noise (Excerpt from the Oakland International Airport Master Plan Update – 2006) Background This report presents background information on the characteristics of noise. Noise analyses involve the use of technical terms that are used to describe aviation noise. This section provides an overview of the metrics and methodologies used to assess the effects of noise. Characteristics of Sound Sound Level and Frequency — Sound can be technically described in terms of the sound pressure (amplitude) and frequency (similar to pitch). Sound pressure is a direct measure of the magnitude of a sound without consideration for other factors that may influence its perception. The range of sound pressures that occur in the environment is so large that it is convenient to express these pressures as sound pressure levels on a logarithmic scale that compresses the wide range of sound pressures to a more usable range of numbers. The standard unit of measurement of sound is the Decibel (dB) that describes the pressure of a sound relative to a reference pressure. The frequency (pitch) of a sound is expressed as Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second. The normal audible frequency for young adults is 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. Community noise, including aircraft and motor vehicles, typically ranges between 50 Hz and 5,000 Hz. The human ear is not equally sensitive to all frequencies, with some frequencies judged to be louder for a given signal than others. See Figure 6.2. As a result of this, various methods of frequency weighting have been developed. The most common weighting is the A-weighted noise curve (dBA). -

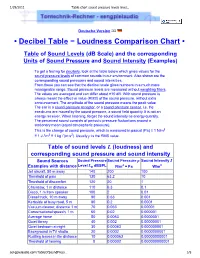

Table Chart Sound Pressure Levels Level Sound Pressure

1/29/2011 Table chart sound pressure levels level… Deutsche Version • Decibel Table − Loudness Comparison Chart • Table of Sound Levels (dB Scale) and the corresponding Units of Sound Pressure and Sound Intensity (Examples) To get a feeling for decibels, look at the table below which gives values for the sound pressure levels of common sounds in our environment. Also shown are the corresponding sound pressures and sound intensities. From these you can see that the decibel scale gives numbers in a much more manageable range. Sound pressure levels are measured without weighting filters. The values are averaged and can differ about ±10 dB. With sound pressure is always meant the effective value (RMS) of the sound pressure, without extra announcement. The amplitude of the sound pressure means the peak value. The ear is a sound pressure receptor, or a sound pressure sensor, i.e. the ear-drums are moved by the sound pressure, a sound field quantity. It is not an energy receiver. When listening, forget the sound intensity as energy quantity. The perceived sound consists of periodic pressure fluctuations around a stationary mean (equal atmospheric pressure). This is the change of sound pressure, which is measured in pascal (Pa) ≡ 1 N/m2 ≡ 1 J / m3 ≡ 1 kg / (m·s2). Usually p is the RMS value. Table of sound levels L (loudness) and corresponding sound pressure and sound intensity Sound Sources Sound PressureSound Pressure p Sound Intensity I Examples with distance Level Lp dBSPL N/m2 = Pa W/m2 Jet aircraft, 50 m away 140 200 100 Threshold of pain -

M-046 Fundamentals of Acoustics and Vibrations

M‐046 Fundamentals of Acoustics and Vibrations Instructor: J. Paul Guyer, P.E., R.A. Course ID: M‐046 PDH Hours: 2 PDH PDH Star | T / F: (833) PDH‐STAR (734‐7827) | E: [email protected] An Introduction to the Fundamentals of Acoustics and Vibrations nd 2 Edition J. Paul Guyer, P.E., R.A. Editor Paul Guyer is a registered civil engineer, mechanical engineer, fire protection engineer, and architect with over 35 years of experience in the design of buildings and related infrastructure. For an additional 9 years he was a principal staff advisor to the California Legislature. He is a graduate of Stanford University and has held numerous national, state and local offices with the American Society of Civil Engineers, Architectural Engineering Institute and National Society of Professional Engineers. He is a Fellow of ASCE, AEI and CABE (U.K.). An Introduction to the Fundamentals of Acoustics and Vibrations 2nd Edition J. Paul Guyer, P.E., R.A. Editor The Clubhouse Press El Macero, California CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. DECIBELS 3. SOUND PRESSURE LEVEL 4. SOUND POWER LEVEL 5. SOUND INTENSITY LEVEL 6. VIBRATION LEVELS 7. FREQUENCY 8. TEMPORAL VARIATIONS 9. SPEED OF SOUND AND WAVELENGTH 10. LOUDNESS 11. VIBRATION TRANSMISSIBILITY 12. VIBRATION ISOLATION EFFECTIVENESS (This publication is adapted from the Unified Facilities Criteria of the United States government which are in the public domain, have been authorized for unlimited distribution, and are not copyrighted.) 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THIS DISCUSSION presents the basic quantities used to describe acoustical properties. For the purposes of the material contained in this document perceptible acoustical sensations can be generally classified into two broad categories, these are: Sound. -

Sound Intensity Measurement

This booklet sets out to explain the fundamentals of sound intensity measurement. Both theory and applica- tions will be covered. Although the booklet is intended as a basic introduction, some knowledge of sound pres- sure measurement is assumed. If you are unfamiliar with this subject, you may wish to consult our companion booklet "Measuring Sound". See page See page Introduction ........................................................................ 2 Spatial Averaging ...…......................................................... 15 Sound Pressure and Sound Power................................... 3 What about Background Noise? ....................................... 16 What is Sound Intensity? .................................................. 4 Noise Source Ranking ........................................................ 17 Why Measure Sound Intensity? ........................................ 5 Intensity Mapping .............................................…......... 18-19 Sound Fields ................................................................... 6-7 Applications in Building Acoustics .................................. 20 Pressure and Particle Velocity .......................................... 8 Instrumentation .................................................................. 21 How is Sound Intensity Measured? …......................... 9-10 Making Measurements ......................................…........ 22-23 The Sound Intensity Probe .............................................. 11 Further Applications and Advanced -

2. Noise Sources and Their Measurement 2.1. Basic Aspects Of

2. Noise sources and their measurement 2.1.Basic Aspects of Acoustical Measurements Most environmental noises can be approximately described by one of several simple measures. They are all derived from overall sound pressure levels, the variation of these levels with time and the frequency of the sounds. Ford (1987) gives a more extensive review of various environmental noise measures. Technical definitions are found in the glossary in Appendix 3. 2.1.1. Sound pressure level The sound pressure level is a measure of the air vibrations that make up sound. All measured sound pressures are referenced to a standard pressure that corresponds roughly to the threshold of hearing at 1 000 Hz. Thus, the sound pressure level indicates how much greater the measured sound is than this threshold of hearing. Because the human ear can detect a wide range of sound pressure levels (10–102 Pascal (Pa)), they are measured on a logarithmic scale with units of decibels (dB). A more technical definition of sound pressure level is found in the glossary. The sound pressure levels of most noises vary with time. Consequently, in calculating some measures of noise, the instantaneous pressure fluctuations must be integrated over some time interval. To approximate the integration time of our hearing system, sound pressure meters have a standard Fast response time, which corresponds to a time constant of 0.125 s. Thus, all measurements of sound pressure levels and their variation over time should be made using the Fast response time, to provide sound pressure measurements more representative of human hearing. Sound pressure meters may also include a Slow response time with a time constant of 1 s, but its sole purpose is that one can more easily estimate the average value of rapidly fluctuating levels. -

Sound Power Measurements on Large Compressors Installed Indoors - Two Surface Method G

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs International Compressor Engineering Conference School of Mechanical Engineering 1974 Sound Power Measurements on Large Compressors Installed Indoors - Two Surface Method G. M. Diehl Ingersoll-Rand Company Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec Diehl, G. M., "Sound Power Measurements on Large Compressors Installed Indoors - Two Surface Method" (1974). International Compressor Engineering Conference. Paper 126. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/126 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Complete proceedings may be acquired in print and on CD-ROM directly from the Ray W. Herrick Laboratories at https://engineering.purdue.edu/ Herrick/Events/orderlit.html SOUND POWER MEASUREMENTS ON LARGE COMPRESSORS INSTALLED INDOORS - TWO-SURFACE METHOD - George M. Diehl Manager, Sound and Vibration Section Ingersoll-Rand Research, Inc. Phillipsburg, New Jersey Sound power ratings of machinery are be 3. Sound power levels of large machines coming important for a number of reasons. are difficult to obtain in most industrial Industrial installations must comply with locations. recently enacted state and local noise con trol codes, and sound power ratings are This situation is changing, and sound needed to predict compliance. In addi power ratings of machinery are becoming tion to this, the Federal Noise Control more important. Recognizing this, the Act of 1972 requires labeling of machinery International Organization for Stand to show maximum noise emission, and this, ardization has decided that all machinery logically, may be in terms of sound power. noise measurement standards must include a procedure for determination of sound The sound produced by a compressor cannot power level. -

Comparative Representation of Sound Field Quantities

Comparative representation of sound field quantities and sound energy quantities Assumption: German: http://www.sengpielaudio.com/VergleichendeDarstellungVonSchall.pdf Air temperarature = 20°C: (Atmospheric pressure 10,1325 Pa = 1013 hectopascal) Density of air at 20°C: = 1.204 kg / m3 (At 0°C is = 1.293 kg/m3) Speed of sound at 20°C: c = 343 m / s (At 0°C is c = 331 m/s) UdK Berlin p Sengpiel Specific acoustic impedance Z at 20°C: Z = · c = = 413 N · s / m3 (At 0°C is Z = 428 N·s/m3) 05.93 v Sound Reference sound field quantities: –5 2 –5 Reference sound pressure p0 = 2 · 10 N / m = 2 · 10 Pa (Fixed "threshold of audibility") p0 p0 –8 –8 Reference sound velocity v0 = = = 5 · 10 m / s (= 4.854 · 10 m / s) c Z0 Reference sound energy quantities: 2 p0 2 –12 2 –12 2 Reference sound intensity J0 = = Z0 · v = 10 W / m (= 0.9685 · 10 W / m ) Z0 J p v Reference sound energy density E = 0 = 00 = 3 · 10–15 W · m / s3 (= 2.824 · 10–15 J / m3) 0 c c –12 2 –12 Reference acoustic power W0 = J 0 · A = 10 W = 1 pW bei A = 1 m (= 0.9685 · 10 W) >>> Given: A plane sound wave of f = 1 kHz and the N Sound pressure p = 1 Pa = 1 = 10 bar 94 dBSPL – We use always the RMS value. m2 Calculated: c 343 Wavelength = = = 0.343 m = 34,3 cm f 1000 1 Periodic length T = = 0.001 s = 1 ms f p 1 Sound velocity v = 2 · · f · = = = 2.42 . -

Measurement and Modelling of Noise Emission of Road Vehicles for Use in Prediction Models

Hans G. Jonasson Measurement and Modelling of Noise Emission of Road Vehicles for Use in Prediction Models Nordtest Project 1452-99 KFB Project 1998-0659/1 997-0223 -.. SP Swedish National Testing and Research Institute SP Acoustics SP REPORT 1999:35 .— 2 Abstract The road vehicle as sound source has been studied within a wide frequency range. Well defined measurements have been carried out on moving and stationary vehicles. Measurement results have been checked against theoretical simulations. A Nordtest measurement method to obtain input data for prediction methods has been proposed and tested in four different countries. The effective sound source of a car has its centre close to the nearest wheels. For trucks this centre ,seems to be closer to the centre of the car. The vehicle as sound source is directional both in the vertical and the horizontal plane. The difference between SEL and LpFn,aduring a pass-by varies with frequency. At low frequencies interference effects between correlated sources may be the problem. At high frequencies the directivity of tyre/road noise affects the result. The time when LPF.,Uis obtained varies with frequency. Thus traditional maximum measurements are not suitable for frequency band applications. The measurements support the fact that the tyreh-oad noise source is very low. Measurements on a stationary vehicle indicate that the engine source is also very low. Engine noise is screened by the body of the car. The ground attenuation, also at short distances, will be significant whenever we use low microphone positions and have some “soft” ground in between. Unless all measurements are restricted to propagation over “hard” surfaces only it is necessary to use rather high microphone positions. -

Sound Fields

Ch01-H6526.tex 19/7/2007 14: 2 Page 1 Chapter 1 Sound fields 1.1 Introduction his opening chapter looks at aspects of sound fields that are particularly relevant to sound insulation; the reader will also find that it has general applications to room Tacoustics. The audible frequency range for human hearing is typically 20 to 20 000 Hz, but we generally consider the building acoustics frequency range to be defined by one-third-octave-bands from 50 to 5000 Hz. Airborne sound insulation tends to be lowest in the low-frequency range and highest in the high-frequency range. Hence significant transmission of airborne sound above 5000 Hz is not usually an issue. However, low-frequency airborne sound insulation is of partic- ular importance because domestic audio equipment is often capable of generating high levels below 100 Hz. In addition, there are issues with low-frequency impact sound insulation from footsteps and other impacts on floors. Low frequencies are also relevant to façade sound insu- lation because road traffic is often the dominant external noise source in the urban environment. Despite the importance of sound insulation in the low-frequency range it is harder to achieve the desired measurement repeatability and reproducibility. In addition, the statistical assump- tions used in some measurements and prediction models are no longer valid. There are some situations such as in recording studios or industrial buildings where it is necessary to consider frequencies below 50 Hz and/or above 5000 Hz. In most cases it should be clear from the text what will need to be considered at frequencies outside the building acoustics frequency range.