California Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma Californiense)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Mutant Genes and Introgressed Tiger Salamander

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Identification of Mutant Genes and Introgressed Tiger Salamander DNA in the Laboratory Axolotl, Received: 13 October 2016 Accepted: 19 December 2016 Ambystoma mexicanum Published: xx xx xxxx M. Ryan Woodcock1, Jennifer Vaughn-Wolfe1, Alexandra Elias2, D. Kevin Kump1, Katharina Denise Kendall1,5, Nataliya Timoshevskaya1, Vladimir Timoshevskiy1, Dustin W. Perry3, Jeramiah J. Smith1, Jessica E. Spiewak4, David M. Parichy4,6 & S. Randal Voss1 The molecular genetic toolkit of the Mexican axolotl, a classic model organism, has matured to the point where it is now possible to identify genes for mutant phenotypes. We used a positional cloning– candidate gene approach to identify molecular bases for two historic axolotl pigment phenotypes: white and albino. White (d/d) mutants have defects in pigment cell morphogenesis and differentiation, whereas albino (a/a) mutants lack melanin. We identified in white mutants a transcriptional defect in endothelin 3 (edn3), encoding a peptide factor that promotes pigment cell migration and differentiation in other vertebrates. Transgenic restoration of Edn3 expression rescued the homozygous white mutant phenotype. We mapped the albino locus to tyrosinase (tyr) and identified polymorphisms shared between the albino allele (tyra) and tyr alleles in a Minnesota population of tiger salamanders from which the albino trait was introgressed. tyra has a 142 bp deletion and similar engineered alleles recapitulated the albino phenotype. Finally, we show that historical introgression of tyra significantly altered genomic composition of the laboratory axolotl, yielding a distinct, hybrid strain of ambystomatid salamander. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of identifying genes for traits in the laboratory Mexican axolotl. The Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) is the primary salamander model in biological research. -

Species Concepts and the Evolutionary Paradigm in Modern Nematology

JOURNAL OF NEMATOLOGY VOLUME 30 MARCH 1998 NUMBER 1 Journal of Nematology 30 (1) :1-21. 1998. © The Society of Nematologists 1998. Species Concepts and the Evolutionary Paradigm in Modern Nematology BYRON J. ADAMS 1 Abstract: Given the task of recovering and representing evolutionary history, nematode taxonomists can choose from among several species concepts. All species concepts have theoretical and (or) opera- tional inconsistencies that can result in failure to accurately recover and represent species. This failure not only obfuscates nematode taxonomy but hinders other research programs in hematology that are dependent upon a phylogenetically correct taxonomy, such as biodiversity, biogeography, cospeciation, coevolution, and adaptation. Three types of systematic errors inherent in different species concepts and their potential effects on these research programs are presented. These errors include overestimating and underestimating the number of species (type I and II error, respectively) and misrepresenting their phylogenetic relationships (type III error). For research programs in hematology that utilize recovered evolutionary history, type II and III errors are the most serious. Linnean, biological, evolutionary, and phylogenefic species concepts are evaluated based on their sensitivity to systematic error. Linnean and biologica[ species concepts are more prone to serious systematic error than evolutionary or phylogenetic concepts. As an alternative to the current paradigm, an amalgamation of evolutionary and phylogenetic species concepts is advocated, along with a set of discovery operations designed to minimize the risk of making systematic errors. Examples of these operations are applied to species and isolates of Heterorhab- ditis. Key words: adaptation, biodiversity, biogeography, coevolufion, comparative method, cospeciation, evolution, nematode, philosophy, species concepts, systematics, taxonomy. -

Western Tiger Salamander,Ambystoma Mavortium

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Western Tiger Salamander Ambystoma mavortium Southern Mountain population Prairie / Boreal population in Canada Southern Mountain population – ENDANGERED Prairie / Boreal population – SPECIAL CONCERN 2012 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Tiger Salamander Ambystoma mavortium in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xv + 63 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the tiger salamander Ambystoma tigrinum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 33 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Schock, D.M. 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the tiger salamander Ambystoma tigrinum in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the tiger salamander Ambystoma tigrinum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-33 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Arthur Whiting for writing the status report on the Western Tiger Salamander, Ambystoma mavortium, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Kristiina Ovaska, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Salamandre tigrée de l’Ouest (Ambystoma mavortium) au Canada. -

California Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma Californiense)

PETITION TO THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION SUPPORTING INFORMATION FOR The California Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma californiense) TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................1 PROCEDURAL HISTORY ................................................................................................................2 THE CESA LISTING PROCESS AND THE STANDARD FOR ACCEPTANCE OF A PETITION ...5 DESCRIPTION, BIOLOGY, AND ECOLOGY OF THE CALIFORNIA TIGER SALAMANDER ....6 I. DESCRIPTION ...............................................................................................................................6 II. TAXONOMY .................................................................................................................................7 III. REPRODUCTION AND GROWTH .....................................................................................................7 IV. MOVEMENT.................................................................................................................................9 V. FEEDING ....................................................................................................................................10 VI. POPULATION GENETICS .............................................................................................................10 HABITAT REQUIREMENTS..........................................................................................................12 DISTRIBUTION -

Sonora Tiger Salamander

PETITION TO LIST THE HUACHUCA TIGER SALAMANDER Ambystoma tigrinum stebbinsi AS A FEDERALLY ENDANGERED SPECIES Mr. Bruce Babbitt Secretary of the Interior Office of the Secretary Department of the Interior 18th and "C" Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 Kieran Suckling, the Greater Gila Biodiversity Project, the Southwest Center For Biological Diversity, and the Biodiversity Legal Foundation, hereby formally petition to list the Huachuca Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum stebbinsi) as endangered pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. 1531 et seg. (hereafter referred to as "ESA"). This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. 553(e) and 50 CFR 424.14 (1990), which grants interested parties the right to petition for issue of a rule from the Assistant Secretary of the Interior. Petitioners also request that Critical Habitat be designated concurrent with the listing, pursuant to 50 CFR 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. 553). Petitioners understand that this petition action sets in motion a specific process placing definite response requirements on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and very specific time constraints upon those responses. Petitioners Kieran Suckling is a Doctoral Candidate, endangered species field researcher, and conservationist. He serves as the Director of the Greater Gila Biodiversity Project and has extensively studied the status and natural history of the Huachuca Tiger Salamander. The Greater Gila Biodiversity Project is a non-profit public interest organization created to protect imperiled species and habitats within the Greater Gila Ecosystem of southwest New Mexico and eastern Arizona. Through public education, Endangered Species Act petitions, appeals and litigation, it seeks to restore and protect the integrity of the Greater Gila Ecosystem. -

Loggerhead Shrike, Migrans Subspecies (Lanius Ludovicianus Migrans), in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Loggerhead Shrike, migrans subspecies (Lanius ludovicianus migrans), in Canada Loggerhead Shrike, migrans subspecies © Manitoba Conservation 2010 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets objectives and broad strategies to attain them and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. -

Rinehart Lake

Rinehart Lake Final Results Portage County Lake Study University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point Portage County Staff and Citizens April 5, 2005 What can you learn from this study? You can learn a wealth of valuable information about: • Critical habitat that fish, wildlife, and plants depend on • Water quality and quantity of your lake • The current diagnosis of your lake – good news and bad news What can you DO in your community? You can share this information with the other people who care about your lake and then plan together for the future. 9 Develop consensus about the local goals and objectives for your lake. 9 Identify available resources (people, expertise, time, funding). 9 Explore and choose implementation tools to achieve your goals. 9 Develop an action plan to achieve your lake goals. 9 Implement your plan. 9 Evaluate the results and then revise your goals and plans. 1 Portage County Lake Study – Final Results April 2005 2 Portage County Lake Study – Final Results April 2005 Rinehart Lake ~ Location Rinehart Lake Between County Road Q and T, North of the Town of New Hope Surface Area: 42 Maximum Depth: 27 feet Lake Volume: 744 Water Flow • Rinehart lake is a groundwater drainage lake • Water enters the lake primarily from groundwater, with Outlet some runoff, and precipitation • Water exits the lake to groundwater and to an outlet stream that flows only during peak runoff periods or during high groundwater levels. • The fluctuation of the groundwater table significantly impacts the water levels in Rhinehart Lake 3 Portage County Lake Study – Final Results April 2005 Rinehart Lake ~ Land Use in the Surface Watershed Surface Watershed: The land area where water runs off the surface of the land and drains toward the lake Cty Hwy T Hotvedt Rd. -

Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta Lynchi)

fairy shrimp populations are regularly monitored by Bureau of Land Management staff. In the San Joaquin Vernal Pool Region, vernal pool habitats occupied by the longhorn fairy shrimp are protected at the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge. 4. VERNAL POOL FAIRY SHRIMP (BRANCHINECTA LYNCHI) a. Description and Taxonomy Taxonomy.—The vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi) was first described by Eng, Belk and Eriksen (Eng et al. 1990). The species was named in honor of James B. Lynch, a systematist of North American fairy shrimp. The type specimen was collected in 1982 at Souza Ranch, Contra Costa County, California. Although not yet described, the vernal pool fairy shrimp had been collected as early as 1941, when it was identified as the Colorado fairy shrimp by Linder (1941). Description and Identification.—Although most species of fairy shrimp look generally similar (see Box 1- Appearance and Identification of Vernal Pool Crustaceans), vernal pool fairy shrimp are characterized by the presence and size of several mounds (see identification section below) on the male's second antennae, and by the female's short, pyriform brood pouch. Vernal pool fairy shrimp vary in size, ranging from 11 to 25 millimeters (0.4 to 1.0 inch) in length (Eng et al. 1990). Vernal pool fairy shrimp closely resemble Colorado fairy shrimp (Branchinecta coloradensis) (Eng et al. 1990). However, there are differences in the shape of a small mound-like feature located at the base of the male's antennae, called the pulvillus. The Colorado fairy shrimp has a round pulvillus, while the vernal pool fairy shrimp's pulvillus is elongate. -

Powder River! Let 'Er Buck!

Fir Tree March, 2012 91st Training Division e-publication POWDER RIVER! LET ‘ER BUCK! 91st Division soldier speaks at Ft. Irwin Huey Retirement page 4 From the Commanding General Fir91st Training DivisionTree Newsletter The 91st Training Division is in full-stride as we ramp up preparations for our summer exercises. The CSM and I plan to visit as many of you as possible over the next Commanding General: few months before the exercises start. A few weeks ago, Brigadier General James T. Cook we had a chance to experience award winning marksman- ship training first-hand while visiting one of the 91st’s Small Arms Readiness Detachments during their Annual Training. Our division is full of talent, so stay-tuned as they compete Office of Public Affairs: in the All-Army Marksmanship Competition. Additionally, 91st Division Soldier honors civilian employer with ESGR we continue to strive for joint certification. We met with the page 5 Director: Commodore of the Navy’s 31st Seabees, Capt. John Korka, and his team to continue our mutual support of their train- Capt. Rebecca Murga ing exercises and integration into our the CSTX and Warrior Exercises. Assistant Director: Please thank your families for their support as you 1st Lt. Fernando Ochoa are away from home more and more through the spring at many workshops and extended meetings. Keep up the great Non Commissioned Officer in Charge: work and stay focused on our goal of providing world class training to the Reserve Forces. Staff Sgt. Jason Hudson Powder River! Editor: Message from the Commanding Gen. & Sgt. -

AMPHIBIANS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION

AMPHIBIANS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION Amphibians are typically shy, secre- Unlike reptiles, their skin is not scaly. Amphibian eggs must remain moist if tive animals. While a few amphibians Nor do they have claws on their toes. they are to hatch. The eggs do not have are relatively large, most are small, deli- Most amphibians prefer to come out at shells but rather are covered with a jelly- cately attractive, and brightly colored. night. like substance. Amphibians lay eggs sin- That some of these more vulnerable spe- gly, in masses, or in strings in the water The young undergo what is known cies survive at all is cause for wonder. or in some other moist place. as metamorphosis. They pass through Nearly 200 million years ago, amphib- a larval, usually aquatic, stage before As with all Ohio wildlife, the only ians were the first creatures to emerge drastically changing form and becoming real threat to their continued existence from the seas to begin life on land. The adults. is habitat degradation and destruction. term amphibian comes from the Greek Only by conserving suitable habitat to- Ohio is fortunate in having many spe- amphi, which means dual, and bios, day will we enable future generations to cies of amphibians. Although generally meaning life. While it is true that many study and enjoy Ohio’s amphibians. inconspicuous most of the year, during amphibians live a double life — spend- the breeding season, especially follow- ing part of their lives in water and the ing a warm, early spring rain, amphib- rest on land — some never go into the ians appear in great numbers seemingly water and others never leave it. -

Towards a Global Names Architecture: the Future of Indexing Scientific Names

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 550: 261–281Towards (2016) a Global Names Architecture: The future of indexing scientific names 261 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.550.10009 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Towards a Global Names Architecture: The future of indexing scientific names Richard L. Pyle1 1 Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, HI 96817, USA Corresponding author: Richard L. Pyle (email address) Academic editor: Ellinor Michel | Received 19 May 2015 | Accepted 20 May 2015 | Published 7 January 2016 http://zoobank.org/AD5B8CE2-BCFC-4ABC-8AB0-C92DEC7D4D85 Citation: Pyle RL (2016) Towards a Global Names Architecture: The future of indexing scientific names. In: Michel E (Ed.) Anchoring Biodiversity Information: From Sherborn to the 21st century and beyond. ZooKeys 550: 261–281. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.550.10009 Abstract For more than 250 years, the taxonomic enterprise has remained almost unchanged. Certainly, the tools of the trade have improved: months-long journeys aboard sailing ships have been reduced to hours aboard jet airplanes; advanced technology allows humans to access environments that were once utterly inacces- sible; GPS has replaced crude maps; digital hi-resolution imagery provides far more accurate renderings of organisms that even the best commissioned artists of a century ago; and primitive candle-lit micro- scopes have been replaced by an array of technologies ranging from scanning electron microscopy to DNA sequencing. But the basic paradigm remains the same. Perhaps the most revolutionary change of all – which we are still in the midst of, and which has not yet been fully realized – is the means by which taxonomists manage and communicate the information of their trade. -

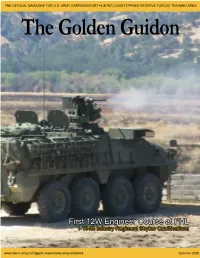

First 12W Engineer Course at FHL 1-184Th Infantry Regiment Stryker Qualifications

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR U.S. ARMY GARRISON FORT HUNTER LIGGETT/PARKS RESERVE FORCES TRAINING AREA The Golden Guidon First 12W Engineer Course at FHL 1-184th Infantry Regiment Stryker Qualifications www.home.army.mil/liggett | www.home.army.mil/parks Summer 2020 Contents Commander’s Message 3 THE GOLDEN GUIDON Chaplain’s Corner 4 Official Command Publication of U.S. Army Garrison Fort Hunter Liggett/ In the Spotlight 5 Parks Reserve Forces Training Area Garrison Highlights 11 FHL COMMAND TEAM Col. Charles Bell, Garrison Commander Training Highlights 20 David Myhres, Deputy to the Garrison Commander Community Engagements 24 Lt. Col. Stephen Stanley Deputy Garrison Commander Soldier & Employee Bulletin 26 Command Sgt. Major Mark Fluckiger, Garrison Command Sergeant Major PRFTA COMMAND TEAM Lt. Col. Serena Johnson, Features PRFTA Commander Command Sgt. Samuel MacKenzie, • Mesa Del Ray Airport 12 PRFTA Command Sgt. Major • Garrison Asian, Pacific GOLDEN GUIDON STAFF Islanders Share Their Stories 16 Amy Phillips, FHL Public Affairs Officer Jim O’Donnell, PRFTA Public Affairs Officer • It’s What’s Inside the Heart, Cindy McIntyre, Public Affairs Specialist Not the Color That Matters 19 The Golden Guidon is an authorized quarterly publication for the U.S. Army Garrison Fort Hunter Liggett community. Content in this publication is not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government or the Dept. of the Army, or FHL/PRFTA. SUBMISSIONS Guidelines available on the FHL website in the Public Affairs Office section. Submit stories, photographs, and other information to the Public Affairs Office usarmy. COVER PHOTO: California National Army Guard Soldiers with the 1-184th Infantry Regiment from Palmdale, conducting annual Stryker Gunnery Qualifications at Fort hunterliggett.imcom-central.list.fhl-pao @ Hunter Liggett, August 5.